Patricia Lent (part 4) on Merce Cunningham: “August Pace”, the first computer dances, falling, losing balance, and “Change of Address”

AM 102. You’ve kindly sent me a preview of Daniel Madoff’s very special new documentary on your 2019 reconstruction of August Pace (1989). It reminds me how wonderfully that work combines natural and counter-instinctive elements in movement: one of the 2019 dancers observes that specific moves are (appealingly) counter-instinctive, yet much of it feels exuberant and dancey. (I think this mixture of the natural and the counter-instinctive is close to what I love in the very different choreography of Frederick Ashton.) Am I right to think that this combination of opposite elements - what the body expects to do and what it finds challengingly surprising/awkward - is close to the heart of Cunningham style?

PL 102. The answer to this question could be a dissertation! But, yes, the disruption of what the body would “naturally” or “organically” do is at the heart of Merce’s choreography. That’s partly due to the element of chance which Merce used to create a random sequence of phrases – this phrase follows that phrase not because they naturally “go together,” but because that is the sequence determined by chance. Part of our job as Merce’s dancers was to figure out how to get from one phrase to the other.

This also has to do with the way Merce analyzed movement – separating the legs, torso, and arms such that any combination was possible. In classical ballet, there are positions, like “first arabesque,” in which the relation of all the body parts is defined and known. In Merce’s work, the positions are an assemblage: one leg to the back, torso tilted, one arm bent, the other straight. Merce was interested in what the body could do, rather than what the body already knew how it do.

Merce’s choreography also has a distinct lack of transitions or what dancers refer to as “preparation steps.” In Merce’s work, you go from this to that, without much in between to help you get from here to there. And the steps that resemble preparations – the triplets and pliés – are given the same value as the “big movements.”

AM 103. Your study of Merce’s notes has taught you how he usually began his formal choreographic preparation by devising a gamut of phrases, and that he often made gamuts of thirty-two or sixty-four phrases, each with different numbers of weight-changes. Thus some works had phrases ranging from no 1 (one weight-change) to no 32 (thirty-two weight-changes) or to no 64 (sixty-four weight-changes).

Am I right that you certainly knew of the importance of composing phrases to Merce’s composition, and of composing a gamut of phrases for each work, but had no notion about this further preparatory issue of varying lengths and numbers of weight-changes?

PL 103. In a 1968 interview, Merce was asked how he went about composing a new dance. “In the simplest possible way,” he responded, “I start with a step.” Anyone who danced for Merce, and probably anyone who took Merce’s class, knew that his dances were constructed of phrases. Short phrases, long phrases, phrases with varying actions, qualities, and characters. He taught us phrases (or “steps”), and then he directed how those phrases would operate in time and space – our facings, our directions, our tempos, our interactions.

When I began studying Merce’s notes, I learned that many of his dances were built from a gamut of 64 (or 32 or 128) phrases. The number 64 corresponds to the 64 hexagrams in the I Ching. As I’ve learned over time, Merce associated each phrase in a gamut with one of the hexagrams, which allowed him to use chance to determine a sequence of these phrases. As John Cage described it, they used the I Ching as a kind of “computer” to generate a random sequence of hexagrams. For Merce’s choreography, this random sequence of hexagrams generated a random sequence of phrases.

In my study of Merce’s notes, I also learned that for many of his dances – not all, but many of the dances from the mid 1970s onward – the number of each phrase corresponded to the number of weight shifts in that phrase. So phrase #5 has five shifts of weight, phrase #43 has 43 shifts of weight. That was an astonishing discovery for me. I was not the first to learn about this, but I have since delved deeply into this aspect of Merce’s work.

August Pace doesn’t follow this pattern. It is constructed of a gamut of 81 phrases which have varying numbers of weight shifts that do not correspond to the number of the phrase.

AM 104. Forgive me if I’ve asked this before, but can you help me define a weight-change? I see how it’s a weight-change to move from standing on two feet to one or from jumping from one foot to two. But if a dancer is arched back on one leg in attitude back but then changes position to attitude front while leaning forward, is that a weight-change? Is a changement - a jump going from two feet to two feet without travelling - a weight-change?

PL 104. The idea of shifting weight is fundamental to how humans move. We walk by shifting from one foot to the other, right/left/right/left. It’s also fundamental to the way Merce thought about and described movement. When Merce said “right” or “left”, he was nearly always referring to the leg you were on. The other leg (or arms, or torso, or head) could be doing all sorts of marvelous things, but your weight was on the right or the left, or both, or (if you were in the air) neither one. That’s why Merce’s notes are chockful of Rs and Ls (rights and lefts).

The weight shifts are also the source of the rhythm which is established by the footfalls rather than the gestures or flourishes. I’d say this is true for ballroom dancing, tap dancing, and a host of other dance forms. It’s the motor underneath the movement.

To your specific questions, yes, a changement is a shift of weight. You start on two feet, then you’re in the air, then you land on two feet. You could have landed on one foot or the other foot, or fallen to the floor, but you landed on two feet, making a shift of weight from two feet to two feet. In a hop, you shift from one foot to the same foot. In a leap, from one foot to the other. As for moving from attitude back to attitude front with a curve - that’s debatable, but I’d say that, if you went from a straight standing leg to plié, Merce would likely call that a shift of weight.

AM 105. Does Merce’s idea of a weight-change always correspond with yours?

PL 105. Always? Probably not. But for the most part the concept of movement as shifts of weight is embedded in Merce’s work. The discoveries I made from studying Merce’s notes confirmed or clarified things I knew from dancing in his company. My reactions were along the lines of “Oh, wow,” and then, “Yes, I see, that makes sense.”

AM 106. And can you say now what significance weight-change had for Merce? As you’ve said, he could make a longish phrase out of a sequence without any weight-change, so what was the big deal in changing the weight? Was he strict or loose in his application of changes of weight?

PL 106. I don’t think the word strict is applicable. Merce used the framework of weight shifts to generate movement. But working within the parameters he devised did not inhibit his inventiveness. Quite the opposite. When I look at his notes I see evidence of puzzle-making, puzzle-solving, and playfulness.

There’s also a lot of arithmetic in the margins of his notes. Phrase # 17 might be 17 distinct shifts of weight; phrase #40 might be a sequence of 8 weight shifts repeated 5 times; phrase #46 might be a sequence of 30 weight shifts, followed by a repetition of the first 16 moves.

The overall duration of a phrase and the rhythm of phrase are another thing altogether. Think about how slowly or quickly, or how evenly or irregularly you can take ten steps. And think about the multitude of things you could do with the rest of your body while taking those steps. But still, it’s ten steps, ten shifts of weight.

AM 107. You’ve said that August Pace (1989) was the work in which Merce began a new interest in falling and off-balance. (I’d like to suggest this was prompted by the 1988 revival of RainForest, which shook up the repertory with its unfamiliar element of wildness.)

Did this interest in falling manifest itself in class? Which parts of the anatomy did it most challenge?

PL 107. I don’t remember whether the off-balance idea showed up in class, but I don’t think so. In August Pace, most of the off-balance occurred in the partnering – the woman taking the movement to an extreme and the man supporting or catching her. The off-balance was an inflection of the phrase.

A few years later, with Change of Address, the idea of falling was embedded in the movement – the phrases careened. We had to catch ourselves, or the phrases actually fell to the floor. It was thrilling!

AM 108. The August Pace score, one of my favourite Cunningham scores, was by Michael Pugliese, who was known to you all as one of the regular Cunningham musicians. Like Mark Lancaster, who had toured with the company a lot, Pugliese knew you all and may have been interested in creating sound environments that would stimulate you without disturbing you as (for example) the score for “Inventions” did. Were there scores that felt as if composed by friends, scores that were performance-friendly for you dancers?

PL 108. Michael Pugliese was an accomplished percussionist. He had studied with Morton Feldman, and was known for his performances of Cage’s work and other new music. But he also played in the orchestra pit for Broadway musicals, and he was a huge fan of the Rolling Stones. His music for August Pace, called Peace Talks, was a celebration of world percussion instruments. He was a dear friend, and he loved the dancers. But I think when he composed Peace Talks he was not thinking about us so much as thinking about himself and Kosugi, and how wonderful it would be to tour the world playing lots of different percussion instruments.

AM 109. If I understand aright, the musical scores for Cunningham dance theatre, as a rule, were meant to be sufficiently indeterminate that neither dancers nor audiences could expect movements and sounds to coincide. (There were some exceptions, such as the scores to BIPED and Split Sides, where the musicians seemed to follow the dancers.) How much were you or your colleagues able to appreciate the differences in one account of the same score or another?

PL 109. I think it was Merce who described the relationship of the music and dance as akin to weather – he used the example of thunder and lightning. During a storm, they occur in the same space and time, but the relationship is indeterminate. The same thing happened with the music – we recognized a particular “storm” or environment and danced within it, but the correspondence between the movement and the music was unpredictable. Audiences often imagine that the dancers are following the music, or the musicians are following the dance, because that is what they’re accustomed to and because the human mind naturally perceives or invents relationships & connections. But it didn’t operate like that.

AM 110. The designs for August Pace were by Afrika (Sergei Bugaev), a Russian artist. The enumeration of the costumes was pointless, but I enjoyed their cut. And, at the risk of sounding too retro for words, I loved their binary black/white colours – though I didn’t need the binary scheme to match your gender - and Jenifer Weaver’s bipartite black/white costume, as if she was the joker in the pack. The set was trivial. Your thoughts and memories?

PL 110. My costume was super-comfortable – black turtleneck and wide-legged black pants. It was a nice break from a unitard. The binary aspect of the design was in keeping with Merce’s work: left or right, open or closed, male or female. I was happy that the male/female binary was expressed here with white & black rather than pants & skirts. I often felt a little ridiculous dancing Merce’s work in a skirt.

The numbers were another oddity with no special significance (and I say that despite being the dancer wearing number one!). At the time, I thought the numbers and the backdrop were Afrika’s nod to randomness.

AM 111. Merce was one of the all-time masters of duet composition – I place him up there with Astaire, Balanchine, and Ashton for duet skill – and it was fabulous to watch him progress from the tight rules he gave himself in the early 1980s (like ice-dance, seldom more than a yard between the dancers, no high lifts) to a much looser style in 1988-1989, with the dancers almost always doing different solos simultaneously, sometimes way distant from each other. And the seven duets of August Pace themselves covered a real gamut.

As you’ve pointed out, Merce planned all these duets as pairs of separate solos with occasional meetings. He had worked that way in the past, but not, I think, in the 1980s.

Did all or most of you feel that these August Pace duets were departures in style?

PL 111. It was the first dance Merce had made since Duets (1980) and Trails (1982) that was constructed almost exclusively of duets. That is, of duets that each occupied the space alone. And each of the duets was very distinctive. I think we all appreciated that.

AM 112. The heart of August Pace is in its duets, much as the heart of Doubles (1984) is in its solos, but in both these works Merce added eye-catching other material: often featuring the “joker in the pack”, Jenifer Weaver, the new soloist who didn’t dance in any duet. At times, this is backing-group choreography; at other times, it’s made of camouflage material that makes us temporarily unaware we’re watching a new duet. What did you discover about these sections from studying Merce’s notes? and/or from reconstructing August Pace in 2019?

PL 112. Some of the “inserts” in August Pace use phrase material drawn from the duet being danced at that time. Sometimes these phrases are done along with the duet dancers, sometimes before, sometimes after. I expect this is what you mean by “camouflage.” The viewer might not realize at first that the phrase being done by the insert dancers is also part of the duet.

More often, though, the material done in the inserts is distinct from the phrases that make up the seven duets. In his notes, Merce labels some of the non-duet material “Shapes for August Pace.” He notates these “shapes” using stick figures (reminiscent of his notes for the 64 “pictures” in Pictures). Many of these “shapes" were included in the dance, such as the opening position with three men holding “a woman" (Jenifer Weaver) horizontally.

Merce’s notes also include descriptions of a few short sequences, almost vignettes. One of these reads: “1 person leaning on one, pushed & bounces off another, lifted by a 3rd, & tossed to a 4th; both separate & fall in different ways, 1st one pulled up by a 5th, both do a roundelay.” This vignette crosses upstage during the duet for Carol Teitelbaum & David Kulick. Kimberly Bartosik is the dancer passed between the other four.

AM 113. Thirty years later, you managed to assemble thirteen of the original cast of fifteen to revive this work - a wonderful coaching feat now recorded on Daniel Madoff’s exciting film documentary. Since you had been a great ensemble, performing together more than any previous Cunningham group and more than any until the 2010-2011 farewell tour, this was a happy reunion.

But you yourself had already begun the work of teaching August Pace to the young dancers. Was the presence of the other twelve useful for just fine-tuning? Or were there are surprises or revelations?

PL 113. The original cast members all taught their own parts from scratch. For the duets, I only taught my part, and the parts danced by Robert Swinston (who wasn’t available) and Chris Komar (who died in 1996). I also taught some of the non-duet material, although Jenifer Weaver taught most of that. Many of the dancers live a long distance from New York City – London, California, Hawaii – so we started with the duets danced by people currently living nearby, and scheduled the rehearsals for the other duets for the second week.

AM 114. Your memories of Polarity (1990)? At the time, it featured tiny elements of same-sex contact that might seem negligible now but felt unusual within the Cunningham context then.

PL 114. I remember that some of the movement was very subtle – isolated movements of the hips, ribs, etc – and some was very athletic. The costumes masked a lot of that, unfortunately.

I remember a short duet I did with Helen that circled in place, and a vigorous trio with Robert and Alan Good in which I leapt up and hung on to one or the other or both, kind of like I was clutching onto tree branches.

AM 115. Any guesses about its title?

PL 115. At the time, no, but recently when I was revising some text for our website, I came across what David Vaughan had written, that Merce had been intrigued by the fact that the dictionary definition of “polarity” refers not only to the separation of two poles but also to their attraction.

AM 116. We have not spoken of Events. (I saw none between 1979 and 1992.) Until this century, Events lasted ninety minutes and usually featured changes of choreographic material from night to night. Can you say why they later became shorter and less varied?

PL 116. I can’t say for sure. I do know that, once Merce began using multiple stages, the Events required more advanced planning. This was after my time, but I’ve heard that there were often several studio rehearsals to work out the timing and transitions between the different stages. That’s a different experience from being given the Event order the day of the show and doing just one run through before the performance. Also, with the multiple stages, a lot more dancing could happen in a shorter period of time.

AM 117. What were the most unusual – and/or stimulating - locations for Events in your time?

PL 117. My first performance was an Event in Madras/Chennai, India, part of a tour of Asia in which we performed only Events. Everything about that tour was unusual. A few years later, we did a wonderful tour around the Mediterranean in which we performed Events in outdoor amphitheaters in Istanbul, Montpellier, and Barcelona. There were bats flying around the stage in Barcelona. Outdoor performances were always an adventure!

But one of the most memorable venues for me was Grand Central Station (1987). The main hall was packed with people who had come especially to see the shows – there were multiple groups performing – and then there were the commuters who came upon the event by chance.

AM 118. Merce liked to say “Wherever you are facing, that is front.” The multidirectionality that ensued was a vital part of Cunningham dance theatre. Nonetheless many Cunningham repertory works include a strong sense of the conventional “front”, even if subtly so. But in Events, especially the Events where audiences were on two, three, or four sides of the stage, it really was true that “front” was wherever you were facing. Some Cunningham dancers found this very disconcerting, others stimulating. You?

PL 118. I loved performing in spaces with multiple fronts. Our performance of Roaratorio at Royal Albert Hall was especially memorable (and challenging). There were no “sides” at all in that circular space.

AM 119. Some Cunningham dancers enjoyed Events less than repertory, others remember some of the great nights of their lives in them. You?

PL 119. Events were an adventure. There was an unpredictability about them that I enjoyed.

AM 120. Merce made a number of short dances that were performed solely as parts of Events. Two of these were first performed in summer 1990, Walkaround Time Falls (August that year) and Four Lifts(September 1990). Your memories of Walkaround Time Falls?

PL 120. The title is misleading – the material did not come from the dance Walkaround Time, but it was designed to be performed in Events in which the Jasper Johns/Marcel Duchamp décor from Walkaround Time was used.

There was a second Event sequence called the Walkaround Time Crossings also made to be done with the Walkaround Time set, but that one didn’t last for long.

AM 121. And your memories of Four Lifts?

PL 121. Most of the material we danced in Events came from repertory dances, but from time to time, Merce would make material especially for Events. Four Lifts was one of those sequences.

It was a series of four lively episodes, each lasting one or two minutes, and each involving one of four women accompanied by two to four men. The movement consisted of various lifts, falls, catches, and off-balance poses. To me, there seemed to be an underlying vaudevillian sensibility, as though we were performing “acts.”

Usually, the sequences made for Events were fairly short-lived, so I was quite surprised when I returned to work for the Cunningham Dance Foundation in 2008 to discover that the Four Lifts, made almost twenty years earlier, was still being done. One of the dancers told me that Merce loved that sequence and used it in many, many Events.

AM 122. We’ve already named a number of MCDC (Merce Cunningham Dance Company) dancers from your era, but are there others you would single out as having especially stimulated Merce?

PL 122. I’ll leave that question alone! Except to say that Merce often seemed stimulated by his newer dancers. He relied on his senior dancers, I’d say, but he was stimulated by the new arrivals.

AM 123. You were one of the six senior dancers on whom Merce made Neighbors, which had its premiere on March 13, 1990. Have you you studied the notes for this? They’re among Merce’s most remarkable. The working title was Hierartic Shaman. Alan Good was given the shaman role.

PL 123. I haven’t looked at the notes for Neighbors.

AM 124. I recommend them. More than with any other work, they suggest the film script for a movie made up of fragmented narratives.

What expressive/acting directions (if any) do you remember Merce giving you in Neighbors?

PL 124. None.

AM. My memory is that at least one of the cast was pleasantly surprised to find Merce directing one sequence as if it was part of a short story, with one character arguing drunkenly.

AM 125. I wrote at the time that Neighbors used every jump in the book and at least half the turns. What challenges do you remember?

PL125. It was exhausting to do. And, yes, we jumped and jumped and jumped.

AM 126. I believe that Neighbors, like Eleven (1988), was a work that excited its dancers until it came to the premiere, when it proved not to have the right alchemy for the stage. Would you attribute this to music and/or design?

PL 126. The title didn’t help.

AM 127. You were in MCDC when Merce began to use the computer in 1989. How and when did you first learn of this?

PL 127. I don’t recall precisely. The only time I saw Merce’s computer was once when he showed some of us a short sequence that he had loaded into it – one of the back exercises. He said it took him a long time to do that. The computer was part of Merce’s choreographic process, but it wasn’t part of our studio work with him.

AM 128. It seems that Merce’s computer interest first bore fruit in Trackers (March 19, 1991), a work in which you did not dance (you and five other senior dancers were in Neighbors, which Merce was making simultaneously). Apart from observing Trackers, did you feel Merce’s use of the computer affecting class or other aspects of your dancing at that time?

PL 128. There was a long walking sequence that we all learned that ended up in Trackers. The arms and legs operated independently both in terms of rhythm and form. This was an early experiment, I think, and he was seeing how it would land. Before long, all of his dances incorporated movement that derived from or was influenced by his work on the computer.

AM 129. “Beach Birds” became the last piece to have a score by Cage. (My memory says he was in the pit, but I believe my memory is wrong here!) Its score is highly atmospheric. The choreography is the most literal (birdlike) of any of Merce’s “nature studies” - almost disappointing in its literal nature - and yet its construction somehow make it riveting. Was it a special piece to be part of?

PL 129. I was recovering from foot surgery when Merce made Beach Birds. He had said that I would enter late in the dance, but in the end, he did not include me. I later took over the role originally done by Vicki Finlayson, but I was not part of the process of making Beach Birds.

In recent years, I have studied and staged Beach Birds and find it a fascinating work. More than any other dance I’ve studied, Merce’s notes surprised me. What I thought I knew as a dance “about birds” was also about chess, a Japanese rock garden, stillness, and two parrots in a pet store window on Bleecker Street.

AM 130. You were in several of the works designed by Marsha Skinner. What do you remember of her at work?

PL 130. I don’t recall meeting Marsha during my time in the company. I was grateful to her for the costumes she designed for Change of Address (1992) – my favorite unitard in a decade of unitards.

In recent years, as part of my licensing work, I have exchanged several letters with Marsha. She has been extremely generous in answering my questions about her designs for Beach Birds and Change of Address.

AM 131. She seems to have been his finest regular designer for many years, since the best Mark Lancaster years. Did you observe any give-and-take or mutual stimulation between her and Merce?

PL 131. Sadly, no.

1: Patricia Lent rehearsing the 2019 reconstruction of Merce Cunningham’s “August Pace” (1989), with Daniel Madoff filming.

2: Patricia Lent and Alan Good in November 2019 demonstrating the final duet that they had created thirty years before in Merce Cunningham’s “August Pace” (1989) - part 1.

3: Patricia Lent and Alan Good demonstrating the next move of the duet they created in Merce Cunningham’s August Pace (1989) - its final duet - in November 2019, at New York City Center Studio 5.

4. Patricia Lent demonstrating a jumping step in August Pace (1989) to two male dancers in November 2019.

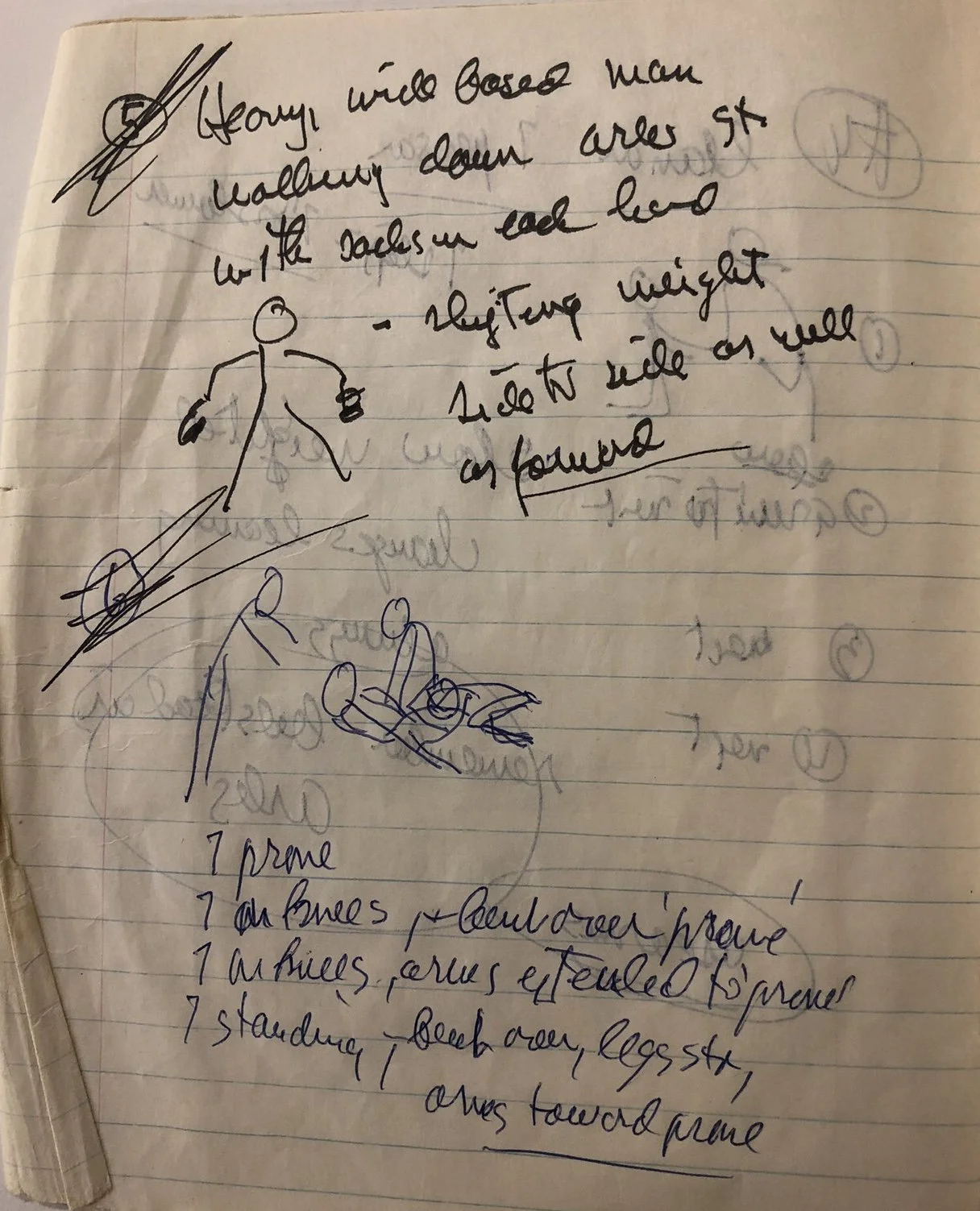

5. Merce Cunningham’s notes for August Pace (1989) include this drawing of a man he had observed in a street in Arles, France. (Reproduced here by kind permission of the Merce Cunningham Trust and New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.) Patricia Lent discusses this in her answer to question 73, in part 2 of this series of email interviews.

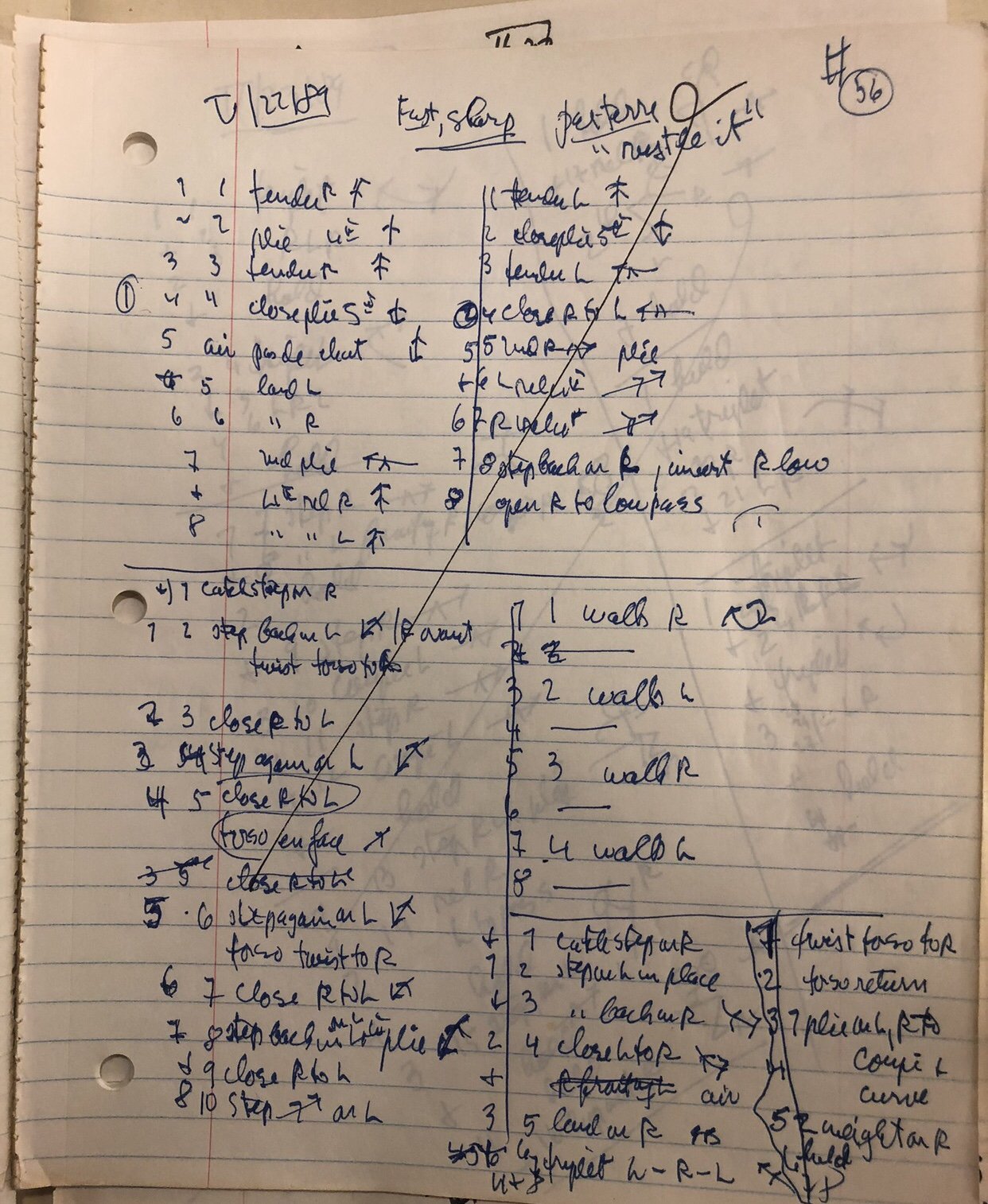

6. When Merce Cunningham was preparing a new work, his dancers became aware of this from the new material that emerged in the classes he taught them. Here is a page of his notes for classroom phrases that he would then work into August Pace (1989) as its phrase #56, one of his gamut of 81 phrases. (See Lent’s answer to question 103.)

A point of interest is that Cunningham, while generally using English-language terminology in the classroom, often used French ballet terms in his preparatory notes: pas de chat, tendu, and so on. (Reproduced here by kind permission of the Merce Cunningham Trust and New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.)

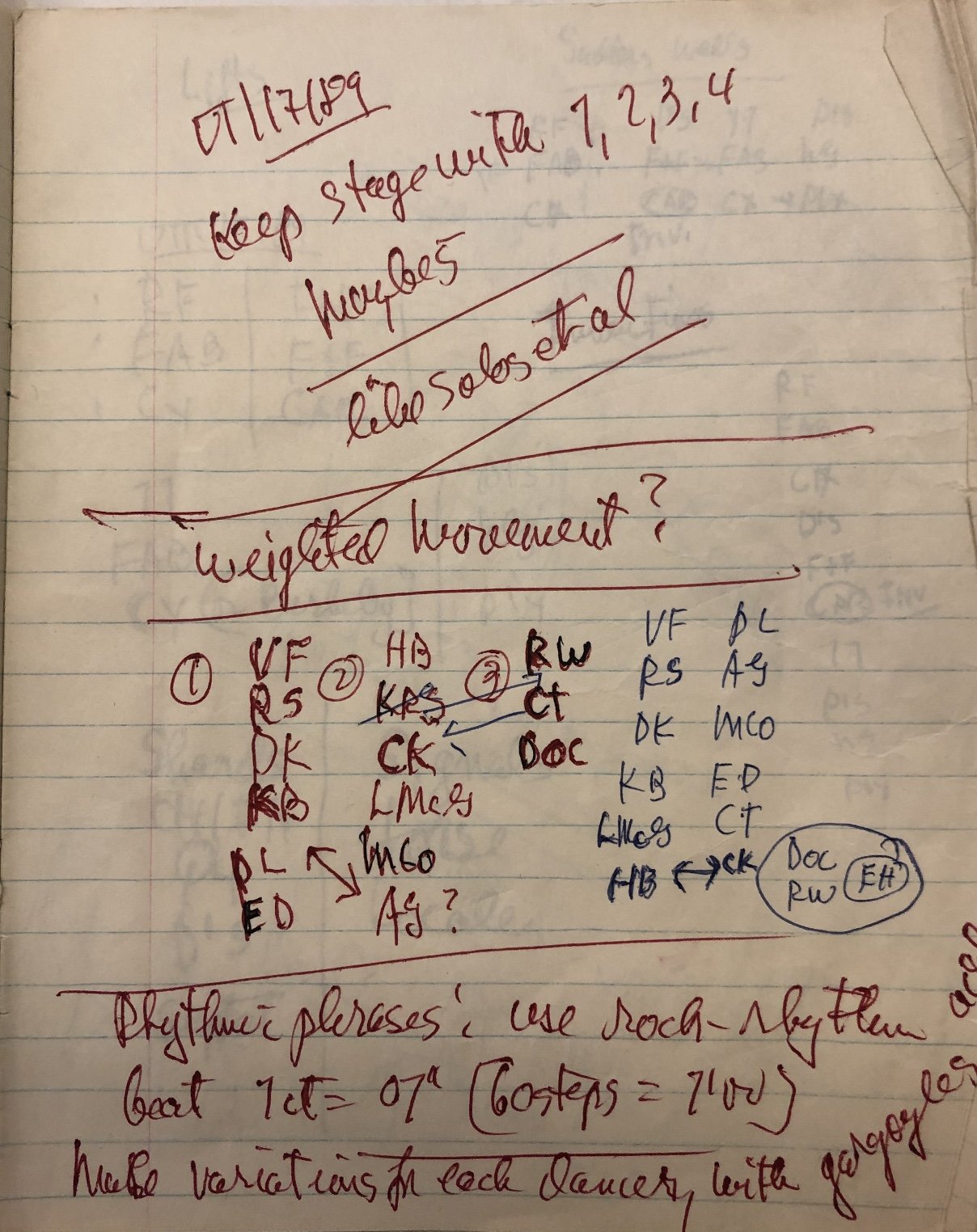

7 For Merce Cunningham, almost every new work was a process of discovery. Very seldom indeed for he start with an idea that remained the defining concept behind the work he then created. Far more often, an initial idea was an ignition key, something to spark his engines; but then he applied chance procedures and other ideas until his original notion had changed out of recognition.

This page, dated 17 June 1989 (“VI/ 17/ 89”), three months before the premiere of August Pace, contains several different layers of Cunningham’s thought. (Reproduced here by kind permission of the Merce Cunningham Trust and New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.) At the page’s centre are the initials of the dancers (twelve and, added later, three) who will perform most of its choreography, but, though they are in two columns, it’s not clear that Cunningham has decided to structure August Pace as a series of male-female duets. The diagonal arrow that connects “PL” (Patricia Lent) to “AG” (Alan Good) may be an early sign of this heterosexual structure. “KPS” refers to Kristy Santimyer, who left the Cunningham company at this time; “RW”, an addition, is Robert Wood, who in the event partnered “HB”, Helen Barrow. “CT” and DOC” are Carol Teitelbaum and Dennis O’Connor. At this stage, there is no mention of “JW”, Jenifer Weaver, who became the significant fifteenth player in the cast, like the joker in the pack. And he has not seen the work as series of seven duets!

Characteristic of Cunningham are the instructions he gives himself and the questions he asks of himself. “Keep stage with 1, 2, 3, 4 Maybe 5” is probably an early version of his eventual decision to limit the number of dancers onstage at any one time in August Pace. The note “like solos et al” probably refers to the way that the duets of August Pace are almost constantly composed as pairs of simultaneous solos. The way “weighted movement?” is presented as a question is very Cunningham: he means to see how far this idea will take him (and is prepared to drop it). In the event, most of the August Pace choreography is indeed weighted; it may contain jumps, but they do not have the aerial quality of some other Cunningham dances.

“Make variations for each dancer, with gargoyles” is a fascinating remark. Certainly August Pace showed that Cunningham was individualising the material performed by each dancer; but the sense of grotesquerie suggested by “gargoyles” is by no means obvious in the finished choreography.