Farewell and thanks to Stomp

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. The news that Stomp, a global phenomenon for over thirty years, finally gave its last performance in New York this January brings a vast wave of memories. Most of these photos are by my former “New York Times” colleague Rachel Papo, but two are from posts by my former London student Simeon Weedall, a lifelong tap dancer who, like Stomp, comes from Brighton and often returned to Stomp as both performer and international stager. Even so, it’s possible that my Stomp memories even antedate his.

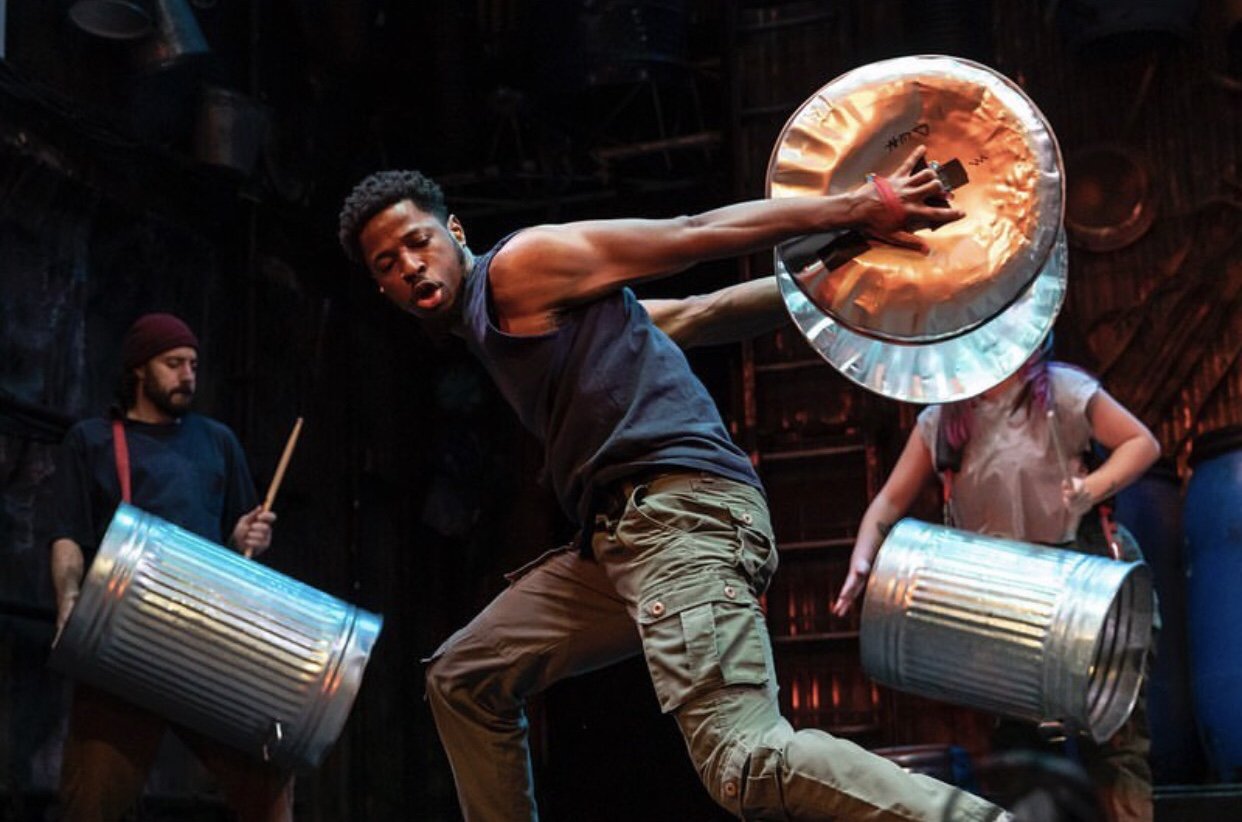

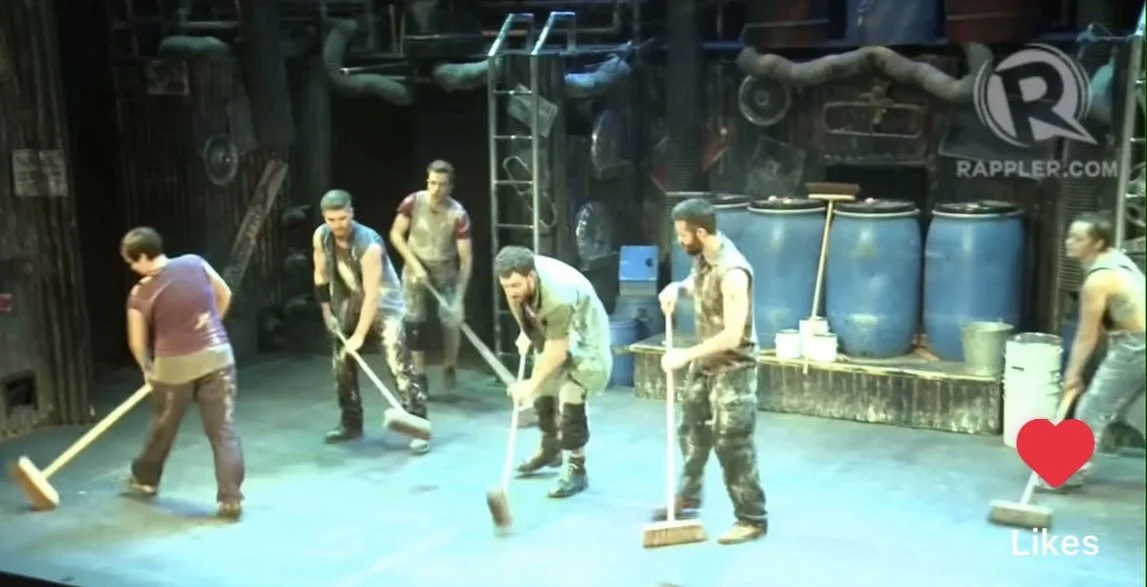

I know that I was the first national/international newspaper critic to single out Stomp and to rave lyrically about it; I did so immediately after seeing it on the Edinburgh Fringe in August (I hope I have the year right) 1992. At the performance I attended, around 11pm, there were all of six of us in the audience. Nothing was known of Stomp other than that it came from Brighton. To me, it was the happiest of revelations: I had no idea it would soon strike the world the same way. I remember the thrill and challenge of trying to summon words to rise to this aesthetic phenomenon, which was music, drama, and, while not quite dance by many definitions, more profoundly and vitally like dance than most of the dance that’s so called. Above all, Stomp was about making rhythm from urban found objects - dustbin lids, brooms, matchstick boxes - and about the excitement of building those rhythms from simple lines into complex polyphony. Eighteen months after my review in the “Financial Times”, Stomp had become such a phenomenon that not only could the press office at Sadler’s Wells not give me ticket for its Sadler’s Wells season, but I then had to stand for ninety minutes to find a return on a cold winter’s night. If that sounds like grumbling, the opposite is true: Stomp was an intoxicatingly happy experience, one that gave me immense pride to have identified before its fame, even if now it seems I was merely the first to have identified a tsunami about to sweep us all away.

Within a very few years, there were eight productions of Stomp playing internationally. Stomp opened in New York in 1995. I remember that I sent a new New York boyfriend to go see it and report back; when he said he wasn’t wild about it, I knew I wasn’t wild about him. On two occasions - approximately in 1998 and 2005 - I interviewed the men whose brainchild Stomp had been about how they kept it going and how they identified its essence; on both occasions, we had wonderful conversations about core aspects of metre and theatricality - about how some performers simply can’t handle counts of 5, about how some 5s are relatively simple but others are truly tricky, and about how some theatrically good performers still don’t have “a rhythmic bone in their body” - conversations of humour, charity, generosity, and enthusiasm.

In 2005 or 2006, the makers of Stomp presented a large Stomp orchestra, its music all consisting of found objects, some of them making noises like brass or woodwind instruments. That occurred in Brighton, but, alas, had no major afterlife. In my head, however, its rich and exuberant textures live on: I can’t forget my excitement.

To everyone at Stomp, my great thanks and congratulations. For over thirty years, they brightened urban life and made naive magic from ordinary materials. I can still taste the innocence and the joy.

Saturday 14 January 2023

1: Stomp.

2: Simeon Weedall in “Stomp”.

3. “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.

4: “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.

5: “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.

6: “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.

7: “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.

8: “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.

9: “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.

10: “Stomp”, photographed by Rachel Papo for the “New York Times”.