Beryl Grey (1927-2022), prima ballerina and artistic director

Beryl Grey (1927-2022, originally Beryl Elizabeth Groom) has died. Many of us will miss her as a friend as well as for her historic importance to British ballet. She was a generous, devoted, inspiring ballerina and dance leader who could sometimes be ludicrous and maddening - many of us did Beryl impersonations - but who tended to prompt intense affection and admiration even from those who could see her sometimes absurd qualities. I knew her from 1987 to 2014, collaborating with her at the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing. The more I worked with her, the more I looked forward to each meeting.

Margot Fonteyn noted, in her 1975 Autobiography, that, while Ninette de Valois (director of the Vic-Welle Ballet, later the Royal Ballet) tended to divide dancers into “little angels” and “little devils”, she ended up giving bigger roles to the little devils. This always amused me, so in 1987 I asked de Valois if it was really true. Yes, on the whole she admitted it had been true. (When I asked “What about Sibley? she shouted “SIBLEY!” back at me. Evidently very much a little devil in her day.) Then de Valois, reflectively, said “But Beryl, I think, was always a good girl.” It remains famous that she took Grey into the Vic-Wells company in 1941 when Grey was still fourteen; that she programmed Grey to perform the double role of Odette-Odile in the complete “Swan Lake” on Greg’s fifteenth birthday; and that she have Grey the title role of Giselle when Grey was sixteen. These were wartime years; de Valois marvelled laughingly at Grey’s prodigious technique (Grey once took her fouetté turns to the left instead of the right when working with an injury). When I asked Beryl about her having always been a good girl for de Valois, she laughed: “It was only because I was so terrified of her!” In a company where women tended to be petite, Grey was tall - and she danced tall, with spectacular legs and arms, theatrical glamour, and tremendous amplitude of gesture and motion.

Grey soon found a rival in the Scottish ballerina Moira Shearer, just a few months older than her, with porcelain-doll features and vivid red hair. In 1981, both ballerinas, long retired from the stage, attended Marie Rambert’s memorial service at St Paul’s Covent Garden. Afterwards, seeing de Valois talking to Clement Crisp, they came up to greet her, then explained they were off to have lunch together. After their departure, de Valois said to Crisp, “Silly girls. When they were with the company, they hated each other so much that they used to position themselves at the barre so that they could kick each other. Now they’re best friends. I’ve got no time for them.” Yet I suspect de Valois would soon have qualified that. It was Shearer with whom de Valois had repeatedly clashed - and who had earned company notoriety (and unpopularity) for her unchecked ambition; de Valois tended to speak of Grey with tenderness and loyalty. (Both women attended many events in de Valois’s honour.) Fonteyn, in her Autobiography, singles out the challenge that Shearer and Grey offered her in 1948 as a defining moment in her career: they raised the bar while she was still in her twenties.

Where Grey acquired any notoriety, it was chiefly for her affectations of speech and, later, her tactless “bricks”. Julia Farron often recalled how, when Grey was receiving her first ballerina roles during the War, she once left the group dressing room with the airy remark “I must fetch a needle and cot-ton.” Such stories of Grey’s errors became well known (at a party for her seventieth birthday, she puzzled everybody by pronouncing Moira Shearer’s first name as if the “Moi” was French, as in “moiré”), yet they did not mar the great respect she earned from all. She herself always spoke of Fonteyn with intense admiration. Gratitude, too: in the 1990s, she still remembered how, in the War when clothes were expensive, Fonteyn would pass on some of her own fashionable coats to her, the teenage Grey. Grey spoke of others with lasting gratitude: of the conductor and music director Constant Lambert, she would explain, with lasting gratitude, how he took time to teach her how to read a musical score.

In 1946, when she was still only eighteen, Grey made her debut as the Lilac Fairy in The Sleeping Beauty when the Sadler’s Wells Ballet reopened the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Her performance of this role became a lasting yardstick - on both sides of the Atlantic. The critic Mary Clarke loved to recall how impressive it was to watch Grey working her way into the Prologue solo variation of the Lilac Fairy in her early performances; the critic David Vaughan loved to recall how, when he crossed the Atlantic to study at the School of American Ballet in 1950, dance people in New York were still talking with awe of how Beryl had performed successive double pirouettes with arms en couronne in that Lilac Fairy variation. That sounds like mere technique (mere!), but when you see Victor Jessen’s live film of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet dancing The Sleeping Beauty in North America - a composite film assembled from 1949-1956 performances - Grey’s double pirouettes and grands ronds de jambe are still breathtaking in their sheer sweep and impulsive generosity: I remember Royal Academy of Dancing students in 1999, after the Jessen film was shown at the Fonteyn Phenomenon conference, exclaiming of Grey and her Sadler’s Wells Ballet colleagues “They really danced”, while acknowledging how exemplary their technique remained fifty years on. When the Covent Garden opera company began after the War, Grey danced in the opening production of Carmen. She won so much applause that David Webster, the Royal Opera House’s director, merrily told her “That’s the last opera of mine you ever appear in.”

As the Lilac Fairy and in many other roles, she had immense warmth onstage, winning a love from the Covent Garden amphitheatre that Shearer (popular in the nearer seats) could never rival. The London audience was often highly partisan: when Alexandra Danilova, now well into her forties, danced Swanilda in Coppélia with the Covent Garden company in 1948, her performance was not flawless; the London devotees made a point of giving more cheers to Grey (who had danced the poetic Prayer solo) than to the Russian prima. Danilova, with perfect manners, let the audience know that Grey indeed deserved the heightened applause.

Frederick Ashton, Leonide Massine, and Robert Helpmann created roles for Grey. Her long and heroic achievement as the Black Queen in Ninette de Valois’s Checkmate (1937) has tended to eclipse that of the role’s originator, June Brae; it was recorded for television. When George Balanchine staged Ballet Imperial (1941) at Covent Garden in 1950, Grey won more unequivocal praise in the soloist role than Margot Fonteyn did in the ballerina one.

Three of Ashton’s several creations for her remain in repertory today. In 1948, she was Fairy Winter in his Cinderella: her variation remains taxing today, and infinitely complex in style, with upper/lower body coordination of fabulous subtlety. In 1952, he created the Vision Scene variation for Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty for her, using Tchaikovsky’s original music (whereas Marius Petipa had used the Gold Fairy music from Act Three); his new solo, marvellously adapting Petipa’s ideas (successive grands battements raccourcis or enveloppés) to Tchaikovsky’s original Vision music, has become so definitive that many have assumed it was part of the Petipa original. (When Peter Martins staged his own Sleeping Beauty for New York City Ballet in 1991, he incorporated the first four-fifths of Ashton’s solo into his, thinking it was Petipa. Had he not added his own coda, the Ashton Estate might have had good cause to sue for plagiarism.) And in 1956 Ashton gave Grey her own variation in Birthday Offering, as the sixth of the Sadler’s Wells Ballets seven ballerinas: with characteristic charm, he chose music with a descending arpeggio that reminded him of Grey’s laugh.

David Vaughan always remembered the jubilant ardour with which she enounced the steps of Aurora’s jumping last entry in Act One of The Sleeping Beauty: four successive jeté variants of rond de jambe sauté as a crescendo. When I mentioned this to Beryl in the 1990s, she at once said “Oh, but Nadia (Nerina) was the one there!” I had to reassure her that, though David had seen Nerina too, it was Beryl’s jump he remembered best.

Grey danced many performances of Giselle, Aurora, Odette-Odile; and she was one of Ashton’s early interpreters of the title role of the three-act Sylvia (still a virtuoso role that challenges today’s ballerinas, not least for sheer stamina). For Massine, she created Death in Donald of the Burthens (1951), his two-scene Scottish dance drama for the Covent Garden company; Alexander Grant, entering his prime as a dance actor, took the title role. It was the only new ballet that created a truly leading role for her: too bad that it did not remain long in repertory.

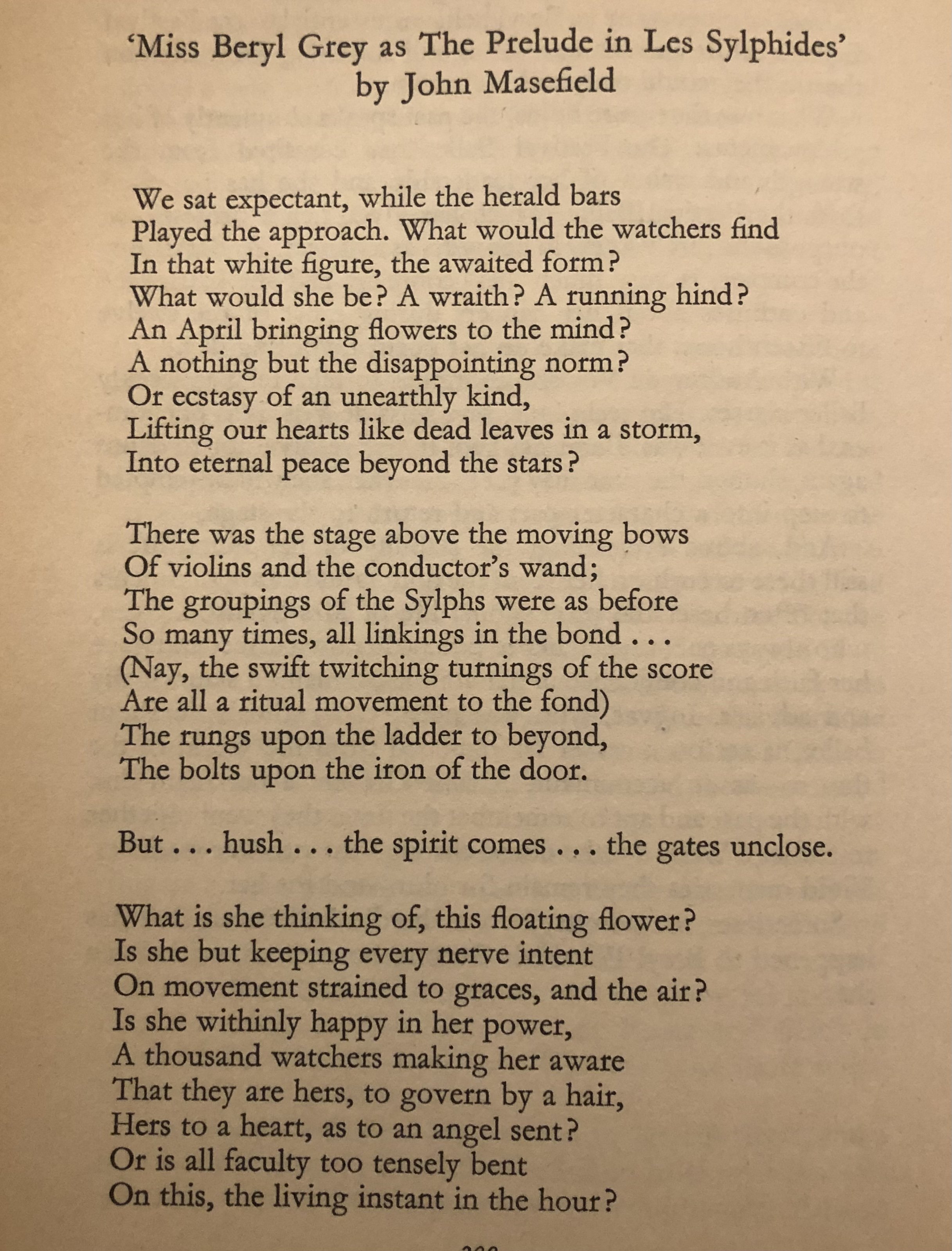

During the Second World War, her dancing had caught the attention of Britain’s long-serving Poet Laureate, John Masefield (1878-1967). He had collaborated in 1938 with the artist John Seago in a Tribute to Ballet in Poems by John Masefield and Pictures by Edward Seago; in 1943, he sent her a signed copy, thanking her for her dancing of the Prelude in Les Sylphides. In 1952 - it must be said the dates differ in various accounts of this poet-ballerina friendship - he wrote an entire new poem, “Miss Beryl Grey as The Prelude in ‘Les Sylphides’”, after seeing her dance it in Oxford. When Grey wrote to thank him, he invited her and her husband, Sven Svenson, to tea at his house in Abingdon. Decades later, she wrote in her autobiography, For the Love of Dance (2017):

“This meeting was the first of many happy hours spent there with this great man of whom I grew incredibly fond. He was powerfully built, erect, grey haired, with handsome features. His deep warm smile was all-enveloping. Like all truly great artists that I have met he was extremely modest and always went out of his way to ensure that Sven and I were comfortable.”

Her prime lasted through the 1950s. On December 15, 1957, she had the honour of becoming the first Western ballerina to dance with the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow; for the rest of her life, she looked back on this as the absolute peak of her stage career. (She always recalled her Bolshoi partner, Yuri Kondratov, as the most admirable partner of her career. With him, she went on to dance in Kyiv and, as it was then, Leningrad.) Her Bolshoi Odette and Odile can be seen on YouTube: the heroic scale of her performance remains marvellous today, and the audacious use of her entire torso stays thrilling.

Grey’s tour of the Soviet Union included Kyiv (Kiev), Tbilisi (Tiflis), and St Petersburg (Leningrad). She danced Odette-Odile in Kyiv, Giselle in Tbilisi and in Leningrad. In Tbilisi, she found some stage business unfamiliar to her in Act Two: an entrance through a trap door and an exit through another trap door (“disappearing into a bed of roses while miming to a sorrowful Albrecht that she gave her blessing to his marriage with Bathilde”, according to David Gillard’s biography of her). Her last Tbilisi Giselle was televised. Between Tbilisi and Leningrad, she returned to Moscow, where the Bolshoi gave her the honour of a gala Swan Lake on January 1, 1958, the eight-hundredth “Swan Lake” in that theatre’s history. In Leningrad, she encountered further unfamiliar stage business in Act Two of Giselle: “At one point she had to be pulled swiftly across the back of the stage on a trolley with one leg stuck up in a holder so that it looked as though she was floating around the woods poised in a perfect but, in the circumstances, thoroughly dangerous arabesque. Then there was much dashing up and down artificial hills, peering through imitation bushes and, finally, a perilous climb up twelve steps into a tree branch. Once aloft in the foliage she had to clamp herself into a hidden metal foot holder and hip rest and the branch was dipped down towards the doleful Albrecht, mooning about below. Standing on one leg, in arabesque, she had to drop flowers in him as he peered up into the tree. After that it was back down the stairs, across the stage and onto the top of her grave before beginning her descent through a trap-door, as the ghost of poor Giselle finally went to ground.” (David Gillard, Beryl Grey, 1977.) In 1964, she was the first Western ballerina to dance with the Peking Ballet. Whereas her appearances in Russia had the distinction of being a guest in the country that might reasonably have been considered ballet’s home - and when the Bolshoi Ballet, fresh from its first triumphs in the West, generated more excitement than any other company in the world, her Chinese appearances involved a missionary element: she not only danced, she staged Les Sylphides there and she taught. She wrote books about both her Russian and Chinese appearances: Red Curtain Up (1958) and Through the Bamboo Curtain (1965).

Some ballet dancers can’t look outside ballet: not so Beryl. When pregnant, she attended the first night of the Martha Graham Dance Company in London, liking to recall that she felt her son’s first kick in her womb just as she observed a Graham contraction onstage.

Between 1968 and 1979, she was artistic director of London Festival Ballet. It’s from this period that she earned her main reputation for saying the wrong thing, once saying “How’s the proud father?” to a principal dancer whose wife had just had a miscarriage, once lecturing the company about the dangers of sunbathing with the words “I don’t want to see any red wilis in Giselle!”, and once, at a planning meeting about Nikolai “Papa” Beriozoff’s new staging of Le Coq d’Or, abruptly inquiring “Well, how long is Papa’s Coq?” At the end of summer seasons at the Festival Hall, she would make old-fashioned curtain speeches abounding with clichés (“I always say ‘There’s no place like home”). All this was spoken with a somewhat mock-regal voice that was widely parodied. Even so, I remember from those speeches that warmth and generosity of hers. She staged or revived important ballets by Bournonville, Fokine, Massine, and Balanchine, ballets otherwise not seen in London at the time, and some never seen since. (My contemporary Matthew Hawkins has written: “Vitally, under Dame Beryl's artistic directorship of Festival Ballet, nascent dance artists of my generation could see ballets with decors by Roerich, Bakst, Benois, Picasso, and Goncharova. We also could see the bravura danse d'ecole works Études and Suite en Blanc. Brit students today can't see live performances of these works - whilst they must listen to lecturers describing the Diaghilev era (for example) and hand in essays. I still feel indebted to the sensibility of Dame Beryl. Live witness of the choreography of Fokine and Massine, in the inspiring/entertaining context of Festival Ballet and its audiences was placed within reach.” Hawkins is right: my own first views of the Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor (Fokine, Borodin, Roerich) and Le Tricorne (Massine, de Falla, Picasso) were with Grey’s Festival Ballet; I have seldom seen them since. Grey also became director of Arts Educational School: the late Mirella Bartrip long remembered how Grey, who never lost her svelte figure, wore unitards every day, and demanded the same maximum-exposure outfits of her students, placing full pressure on them to emulate her enduringly glorious physique.

Her régime at Festival Ballet came suddenly to an unhappy end in 1979. In her 2017 autobiography, For the Love of Dance (Oberon Books, 496 pages), Grey recounts this period in considerable detail. What’s grimly fascinating is that the plot to oust her seems to have emanated from her sometime-friend and sometime-foe Rudolf Nureyev and his scheming henchman Charles Murland. Nureyev, now entering his forties and whose great virtues Grey extols, was looking for a company to run; Murland, a Festival Ballet board member whom Grey simply describes as “nasty”, did Nureyev’s bidding. (Murland died in the 1980s. During his lifetime, I asked Clement Crisp what he was like. Clement replied “He thinks the sun shines from whichever orifice Rudolf Nureyev cares to point in his direction.” On his death, Midland’s ballet papers passed to the Royal Academy of Dance, where Clement, its librarian, was amused to find old evidence of Murland’s various ballet schemes going back to the 1960s.) Grey had taken Festival Ballet to triumphs in both New York (1978) and China (1979) when Nureyev (furious not to be allowed to join the company in China and keen in his forties to direct a prestigious company) and Murland engineered her downfall. Grey relives her distress and confusion in her memoirs, which are evidently based on diaries; yet she keeps finding every opportunity to give praise where it’s due and to avoid bitterness.

I met her - and clashed with her - when I became chief examiner in dance history to the Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing. I had drawn up a syllabus that was approved in detail by other members of the I.S.T.D. at successive committee meetings - only to find, on my first meeting with Beryl, that she wanted all kinds of immediate changes to it. Her manner seemed inconsiderate, tactless, annoying; I was furious. Yet when I began to make those changes, I encountered the other side of Beryl: she was practical, involved, enthusiastic, eager. Her problem, it soon emerged, had been that my syllabus looked too ballet-dominated: it wasn’t, but she wanted it reconfigured so that the non-ballet elements caught the eye from the first - an admirable idea that went straight to my heart. From then on, and well into her eighties, I would receive an annual Christmas card, thanking me effusively for all my work. I soon viewed her as a real-life Lilac Fairy: she really did want all to be well, and she knew how to fill the air with joy. She could also be inimitably blunt. One year, when I set an examination about the collaboration of Ninette de Valois and Frederick Ashton in the development of the Royal Ballet, she exclaimed “Collaboration? There wasn’t any!” Speaking of Balanchine, she glowed with the memory of the 1950 Ballet Imperial, while recalling how one tended to acquire tendinitis from his demand to work more on the front of the foot than ever before. When London Festival Ballet changed its name to English National Ballet in 1987, I remember her simply and sensibly saying “I wish they’d keep the word ‘Festival’”. (Instead its revised name has proved foolish, seeming to make it parallel to the entirely dissimilar English National Opera, and, this century, to align it at one point with the right-wing British National Party. Few of the company’s leading lights are either English or British.)

In 1999, Grey and I worked together again, when she spoke at the opening of the Royal Academy’s Fonteyn Phenomenon conference. In those later years, I began to see a touching new vulnerability in her; she remained engaging and enthusiastic. Monica Mason often included her in Royal Ballet events: there is a Nuñez-Soares DVD of the Anthony Dowell Swan Lake where the most touching and interesting ingredient is the appendix, in which Grey, Mason, Lesley Collier, and Nuñez speak - with no man on screen - of their memories of dancing Odette-Odile.

I last saw Grey at an Ashton programme at 2014 at Covent Garden. I knew she had danced Scènes de ballet; she was thrilled that I had known, and delighted to recall the challenges of that ballet. She was in her mid-eighties: her affectionate warmth haunts my memory. But my favourite story of her was told to me by my friend Phrosso Pfister, a passionate teacher of dance history herself, who had been the one to introduce me to the Imperial Society in 1987. Phrosso related how she had stood in the foyer at a Sadler’s Wells gala in honour of Beryl, probably in the 1990s. As Grey was being conducted through the foyer as the evening’s great celebrity, she, spotting Phrosso, simply broke with ceremony to cross over and greet Phrosso as a particular friend. Phrosso, a modest woman, was neither a celebrity nor a glamourpuss, but Beryl knew her as a valued and beloved colleague who had given her life to dance, as Beryl had hers.

Saturday 10 December

1: Beryl Grey as the Lilac Fairy in The Sleeping Beauty.

2: Beryl Grey as the Lilac Fairy in the Panorama Scene of The Sleeping Beauty, with Margot Fonteyn as Princess Aurora and Robert Helpmann as the Prince.

3: Beryl Grey as Giselle.

4: Beryl Grey as Giselle.

5: Beryl Grey as the Black Queen in Ninette de Valois’s Checkmate.

6: Beryl Grey as the ballerina of Frederick Ashton’s Scènes de ballet.

7: Beryl Grey as Fairy Winter in Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella (1948).

8: Beryl Grey as Princess Aurora in The Sleeping Beauty.

9: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake.

10: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

11: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

12: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

13: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

14: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

15: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

16: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

17: Beryl Grey in the YouTube Pathé newsreel of her 1958 Bolshoi Ballet appearance as Odette-Odile in Swan Lake, with Yuri Kondratov as Prince Siegfried.

19: Beryl Grey as Princess Aurora in Act Three of The Sleeping Beauty, 1951-1952, Sadler’s Wells Ballet at Covent Garden. Photo: Roger Wood.

20. The first half of John Masefield’s poem on Grey as the Prelude in Les Sylphides.

21: The second half of John Masefield’s poem on Grey as the Prelude in Les Sylphides.

22: The seven ballerinas of the original cast of Frederick Ashton’s Birthday Offering (1956) in a famous photograph by Roger Wood. Left to right: Svetlana Beriosova, Rowena Jackson, Elaine Fifield, Margot Fonteyn, Nadia Nerina, Violetta Elvin, Beryl Grey. With Grey’s death, Jackson is now the only survivor of the seven.

23: An enchanting photograph, taken by Beryl Greg’s husband Sven Svenson, of two historic ballerinas together: Maya Plisetskaya, applying her special “fish-scaler” (used to remove the rough surfaces of ballet shoes) to Grey’s point shoes. Plisetskaya and Marina Semyonova were among the Bolshoi ballerinas who paid tribute to Grey’s Odette-Odile in 1958.