The twentyfirst-century woman choreographer, Pam Tanowitz: Women’s History Month in Dance, 2021

Women’s History Month in Dance 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39. There have been women choreographers of greatness since the beginnings of modern dance - and probably a few before that. But Pam Tanowitz is the one who unaggressively establishes the sexual politics principles of twentyfirst-century dance theatre on a newly high level. Like a number of dance-makers of the past forty years, she choreographs for men and women as equals and owning their space and moment on equal terms, and for same-sex couples and opposite-sex couples as equals. Like Mark Morris and Alexei Ratmansky, she shows a profound fascination with dance history, recalling a range of choreographers from Marius Petipa to Twyla Tharp. But no choreographer alive makes a more marvellous use of footwork (and her own company’s feet are both bare and beautiful). No choreographer has more powerfully or poetically mastered the spatial multidirectionality of Merce Cunningham’s example. And no choreographer has developed a more radical idiom of choreographic counterpoint with music.

It’s very exciting to attend the premiere that takes an already very good choreographer into greatness; it’s both exciting and alarming to review that premiere. I’d been watching Tanowitz’s for at least nine years, always admiring it, when, in 2018, I had the fortune to attend the world premiere of “Four Quartets” at Bard College. At the time, I was the chief dance critic of the “New York Times”. So it was my privilege to write a couple of big superlatives: “After one viewing, on Saturday night, I’m inclined to call this the most sublime new dance since Merce Cunningham’s ‘BIPED’ 1999)” in my opening paragraph and, in my last paragraph, “If I am right to think this is the greatest creation of dance theater so far this century, we’re fortunate that “Four Quartets” will travel to other stages.”

Publicity, of course, soon converted the second quotation into “the greatest creation of dance theatre so far this century” (“New York Times”); and now I find that some think I was the one who put Tanowitz on the map. No : she did. There are times when readers let you know if they think you’ve gone too far. The world premiere of “Four Quartets” was not one of those. Since I had told the “NY Times” two months before that I was stepping down (the announcement had not yet been made), I had no career reason to hail another choreographer among the greats; I was merely recognising what was before my eyes.

Tanowitz, then in her late forties, had been making dances for many years. As she said in a 2019 interview, “It took me twenty-five years to become an overnight success.” What tipped Tanowitz into greatness was not my review but Bard College, which gave her the resources and the advance planning to think big, applying herself to TS.Eliot’s famous poems with top-level designs (Brice Marden and Clifton Taylor) and music (Kaija Saariaho). Her dramaturg Gideon Lester had taken her to the four physical locations used by Eliot in naming his quartets. Just as Mark Morris made his greatest-to-date work in 1988 when the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels, gave him the large-scale theatrical and musical resources to stage Handel’s “L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato”, so Bard, with its Gehry theatre (new in 2003), did the same for Tanowitz.

And those twenty-five years built up Tanowitz’s resources. She invariably pays tribute to her teacher, Viola Farber (1931-1998), whose lessons in dance and choreography seem still to be percolating through Tanowitz’s mind. In the years 2009-2017 - I especially hope we see again her “Sequenzas in Quadruilles” (2016) - it was evident that she had a big and complex talent, that she was planning works that could span ninety minutes, that she was witty and loved footwork (the two often coincide), that she was steeped in Merce Cunningham technique and in aspects of Cunningham dance theatre (not least multi-directionality in space), and that she was investigating radical counterpoint between music and choreography. Her “New Work on Goldberg Variations” (2017), premiered at Duke Performances, though less Diaghilevian in its visual design elements, is very remarkable in the way that - with pianist Simone Dinnerstein playing centre stage and the dancers moving around her and the piano - it takes its dancers and audiences through a spectrum of unorthodox choreographic musicalities, with dance and music seeming to converse as equals but never as mirror images.

A number of women choreographers have gone international because of the recent trend of promoting female dance-makers in ballet. Tanowitz’s association with ballet companies and pointwork goes back maybe eleven years, to pieces she’s made for the chamber-scale New York Theatre Ballet. In 2019, she created for the Royal Ballet and New York City Ballet; currently she’s in Australia preparing a new work for the Australian Ballet. Balanchine and Ashton are among the master choreographers she’s researched. Ballet is a sexist art, predicated on the dualism of gender (she goes on point, he partners); to Balanchine’s dictum “Ballet is woman”, she has replied “Ballet is woman as seen by men.” But no choreographer today makes less sexist ballets than she, with pointwork sometimes given to peripheral dancers rather than the leads, and with same-sex and female-male partnering part of the mix.

And let no Covent Garden or Lincoln Center mentalities assume that she’s becoming part of the ballet super-race. Tanowitz’s use of bare feet is gorgeous; and, like Cunningham but few others, she knows how to make those bare feet register far and high across big three-tier auditoria. I have the feeling she’s only just beginning. To know where the dance theatre of our time is heading, you have to follow her work.

Saturday 13 March

30: Pam Tanowitz

31: Pam Tanowitz, in the September 2020 New York City Center Studio 5 Live @ Home session, where she worked on choreographing a solo for Sara Mearns online via StreamYard.

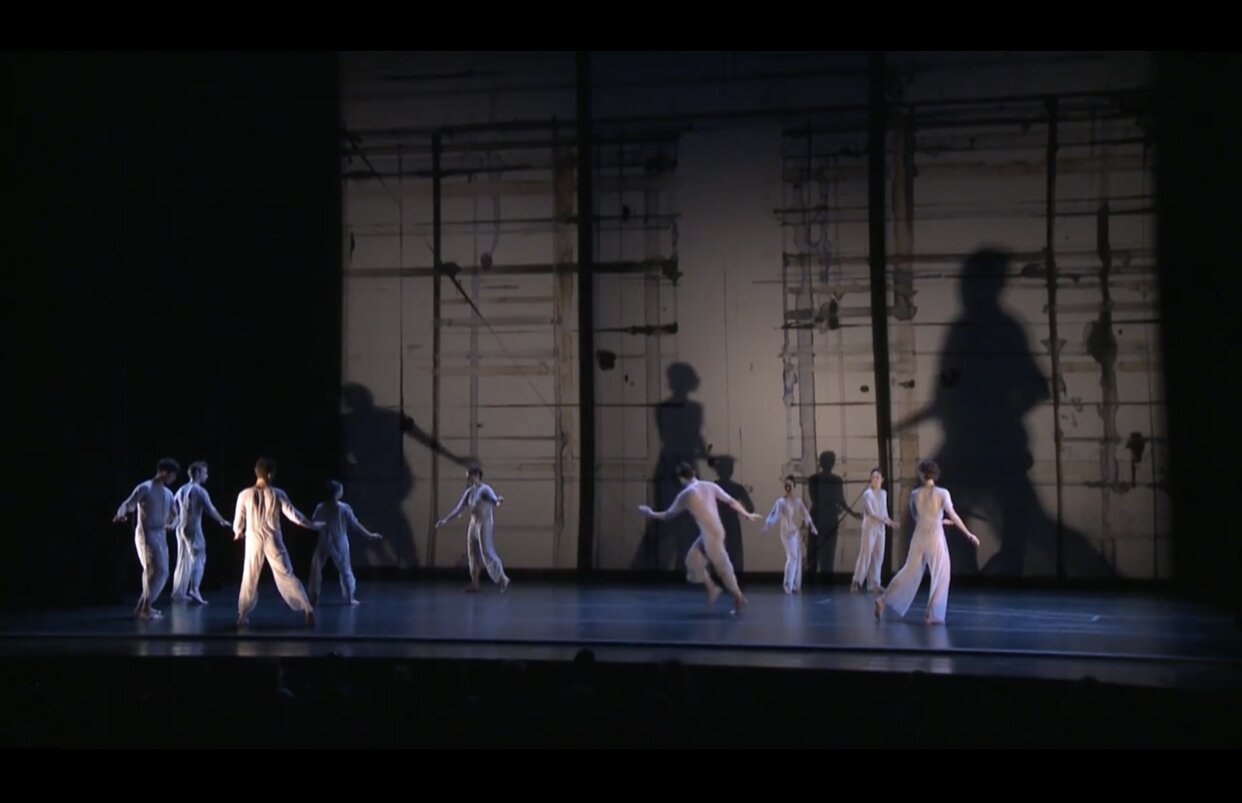

32: a moment from the final section of the Pam Tanowitz “Four Quartets” (2018).

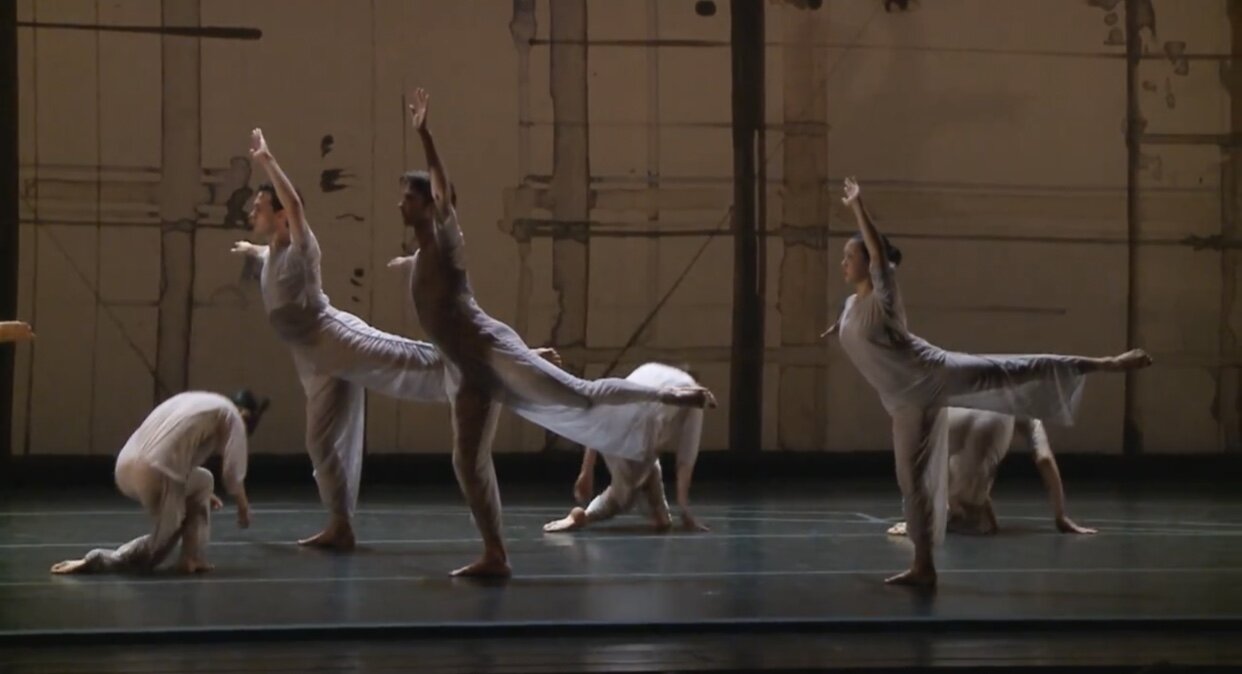

33: a moment from the final section of the Pam Tanowitz “Four Quartets” (2018), with Lindsey Jones centre stage.

34: a moment from the final section of the Pam Tanowitz “Four Quartets” (2018).

35: a moment from the final section of the Pam Tanowitz “Four Quartets” (2018).

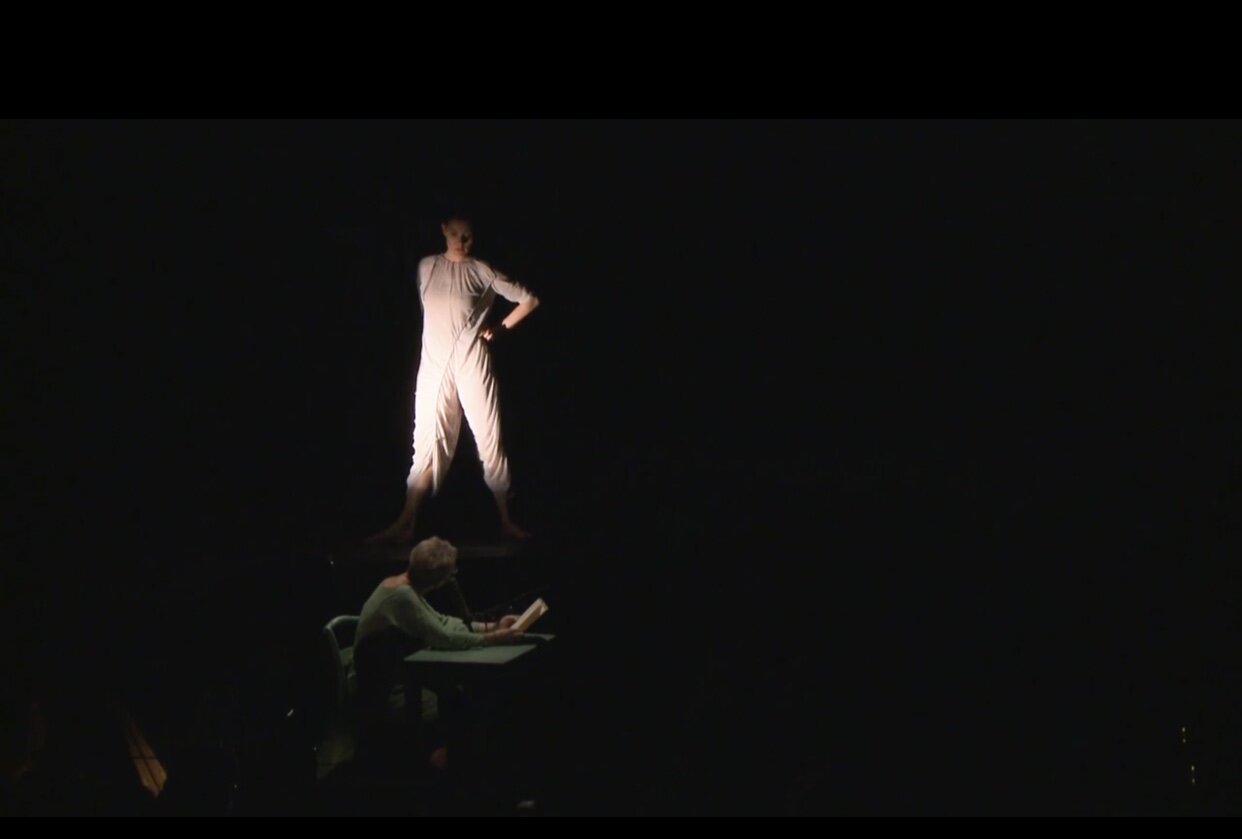

36: a moment from the final section of the Pam Tanowitz “Four Quartets” (2018), with Melissa Toogood onstage close to Katherine Chalfont speaking the T.S.Eliot poem in the orchestral area.

37: a moment from the final section of the Pam Tanowitz “Four Quartets” (2018).

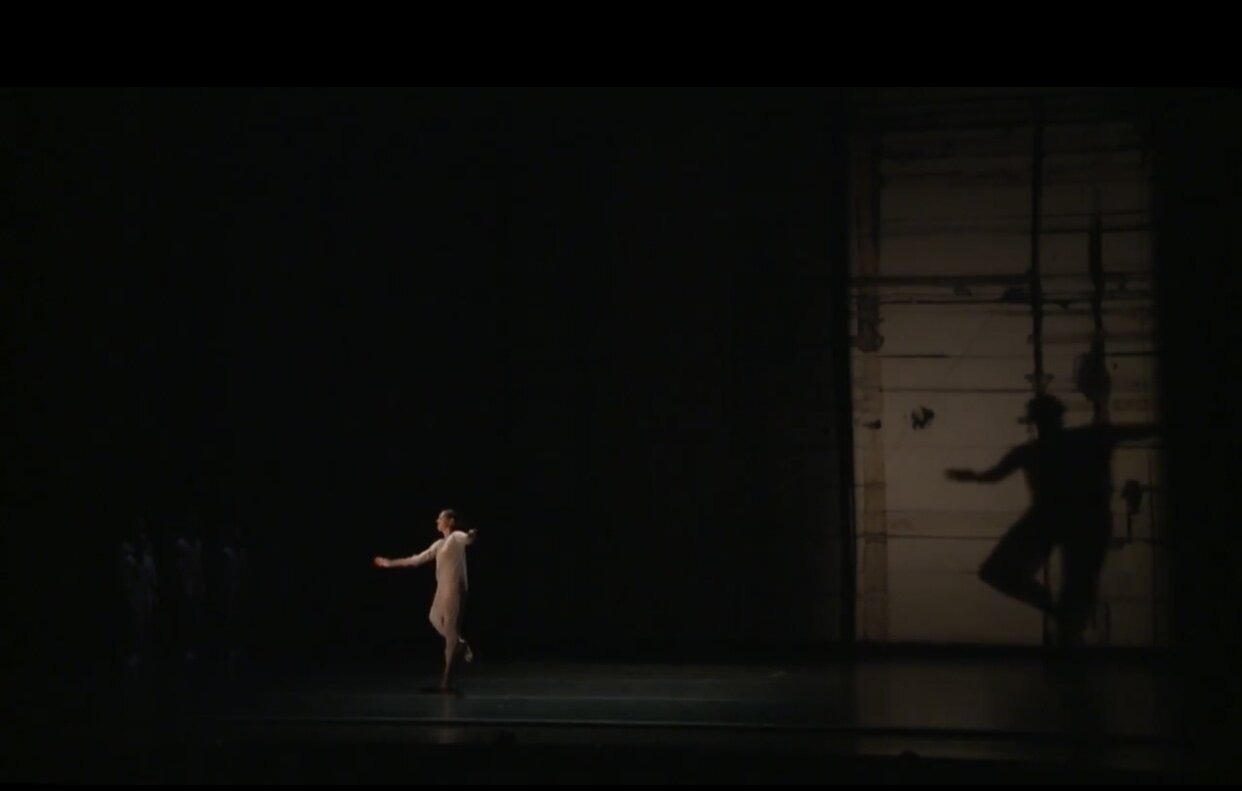

38: a moment from the final section of the Pam Tanowitz “Four Quartets” (2018), with Lindsey Jones in tendu front, as if saying “Let’s begin”, at the end of the work.