The powerfully original Bronislava Nijinska: Women’s History Month in Dance, 2021

Women’s History Month in Dance 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48. Few figures in dance history better deserve to be rescued from relative obscurity than the often forgotten Bronislava Nijinska (1891-1972). So it was good news, last weekend, to hear the super-intelligent dance historian Lynn Garafola say, on line, that she had completed the Nijinska biography on which she has been working for many years.

Nijinska - who began choreographing in Russia during the First World War, and then came west in 1921, just when Diaghilev needed a new choreographer - was one of the most powerfully original of all teachers and choreographers. Before the First World War, she had created roles for both Mikhail Fokine (a Street Dancer in “Petrushka”) and her brother Vaslav Nijinsky; her “Early Memoirs” about those years may be the most intelligently vivid of all ballet autobiographies. In her own choreography, she often went beyond Fokine and her brother, while showing the influence of both. Her use of the upper body and of sculptural groupings, her new-age view of sociologies traditional (“Noces”) and modern (“Biches”) thrillingly combined of ballet’s lineage and the totally unorthodox. She collaborated with Serge Diaghilev and Jean Cocteau, with the composers Auric, Milhaud, Poulenc, Ravel, and Stravinsky, with the painter-designers Bakst, Benois, Braque, Gontcharova, Laurencin, and with the costumière Coco Chanel.

She exerted a powerful influence on George Balanchine (who never admitted it) and Frederick Ashton (who paid lifelong homage to her). As a teacher - Ashton, when describing her 1928 classes, made them sound like Merce Cunningham’s thirty or more years later - she helped to train many important dancers, not least Maria Tallchief, Robert Barnett, Allegra Kent, all three to be central to New York City Ballet. When Ashton came to choreograph for City Ballet in 1950, he quickly asked Barnett if he had been a Nijinska student. When Barnett said yes, Ashton replied “She is an encyclopaedia of the dance.”

Only a few dances choreographed by Nijinska have survived her death, however. Of these, the most widely known are those in the 1935 Hollywood movie of Shakespeare’s play “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, directed by Max Reinhardt and William Dieterle. But there’s nothing like knowing dances from living theatrical repertory. In this respect. London audiences, between 1966 and 2012, were luckier than those anywhere else in the world: they could revisit Nijinska’s masterpieces, “Les Noces” (1923) and “Les Biches” (1924) in successive seasons. (Both ballets have been staged in America and France, but not regularly revived.) Once you’ve absorbed “Noces” and “Biches” from successive viewings over twenty-five years, you start to spot Nijinskaisms in other people’s choreography: I now wonder why it took me so long to see them in the muse ensembles in “Apollo”, in the Siren in “Prodigal Son”, in group sequences and tableaux in “Serenade”, and - though less obviously - in Balanchine’s mature work from “Concerto Barocco” (1941) to “Stravinsky Violin Concerto” (1972).

Then there are the lost Nijinska ballets that suggest how much more she had to offer. In “Les Fâcheux” (1924), to a commissioned score by Georges Auric and designs by Georges Braque, she gave herself the male role of Lysandre, while Anton Dolin as L’Élégant danced on point. (It sounds as if it would be modern in the 2020s.) Her “Chopin Concerto” (1937) was recalled by Alexandra Danilova in the 1980s as one of the finest pure-dance ballets of the twentieth century; its response to a concerto prefigured the many responses to concertos that Balanchine began to make from 1940 onward. (Several Nijinska ballets have been reconstructed since her death, including “Le Train Bleu” and “Bolero”. Other viewers have received these with less scepticism than I.)

Since her inventiveness was so potent, it’s distressing that her creativity came to an end long before her death: she made few works after the early 1940s. This seems to have been a pattern for many women choreographers in ballet: the gifts that originally made Marie Sallé, Fanny Cerrito, Lynn Seymour striking dance-makers may have burnt out. If I’m right about this, we should deduce that even the most individual women choreographers in ballet can’t sustain creativity in a world largely shaped by and for men, despite the high proportions of women dancers. Nijinska could be brusque and tough, qualities more easily condoned in creative men than in creative women.

What can it have been like for her to look for employment in capital cities where Balanchine and Ashton were becoming all the rage? Although it was Ashton who, in the 1960s, brought “Biches” and “Noces” back into the limelight, he may have known what I once heard, that she had once bitterly complained that his highly successful “Apparitions” (1936) was a rip-off of her “La Bien-Aimée” (1928). For whatever reasons, Ninette de Valois - who admired Nijinska greatly - never invited her to choreograph for what became the Royal Ballet; Lucia Chase took Nijinska as one of the founder-choreographers of American Ballet Theatre, but did not keep her there long.

From 1940, Nijinska was based in Los Angeles. That’s where she taught such dancers as Maria and Marjorie Tallchief, Robert Barnett, and Allegra Kent. Even then, the training she gave dancers did not accord with that given by Balanchine. To Maria Tallchief , he said “You know, dear, you would be a good dancer if only you could do tendu” - and duly retrained her from her tendus up. Around 1951, Nijinska asked Barnett to assist in a New York demonstration of her teaching, but he declined because he knew that his style had been entirely overhauled by Balanchine. But even though Balanchine training has become widely influential, nobody has suggested Nijinska’s teaching was deficient: it simply had very different points of emphasis. A Nijinska dancer would be wrong for “Divertimento no 15” or “Agon”; a Balanchine dancer would be wrong for “Noces ” or “Biches” (though the corps women’s hops in relevé fifth in Balanchine’s “Concerto Barocco” are very Nijinska indeed, as is the emphatically chic épaulement with which the “Prodigal Son” Siren briskly struts on point across the stage).

Yet if only “Les Noces” and “Les Biches” were to remain - it’s possible that, under Kevin O’Hare, they may be permanently dropped from the Royal Ballet’s repertory - they would be compose one of the most impressively dissimilar pairs in all art. How could the same person have made works so unalike? “Noces”has virtually none of the drastic épaulement or chattering batterie that are so striking in “Les Biches”. And the percussive pointwork and reduced physical stretch that make the body language of “Noces” so haunting are far from the debonair brio of “Biches”. “Noces” analyses a traditional Russian society that has not changed; “Biches” satirically celebrates the sexually ambiguous mores of a modern Riviera society. These two suffice to tell us that Nijinska was among the greatest choreographers in history. If you know neither or even only one of them, your sense of twentieth-century dance is highly incomplete.

Sunday 14 March

40: Bronislava Nijinska.

41: Bronislava Nijinska

42: Bronislava Nijinska in “Kikimora”in the ballet “Contes Russes”. Photograph: Man Ray.

43: Bronislava Nijinska as the Hostess in her 1924 ballet “Les Biches”

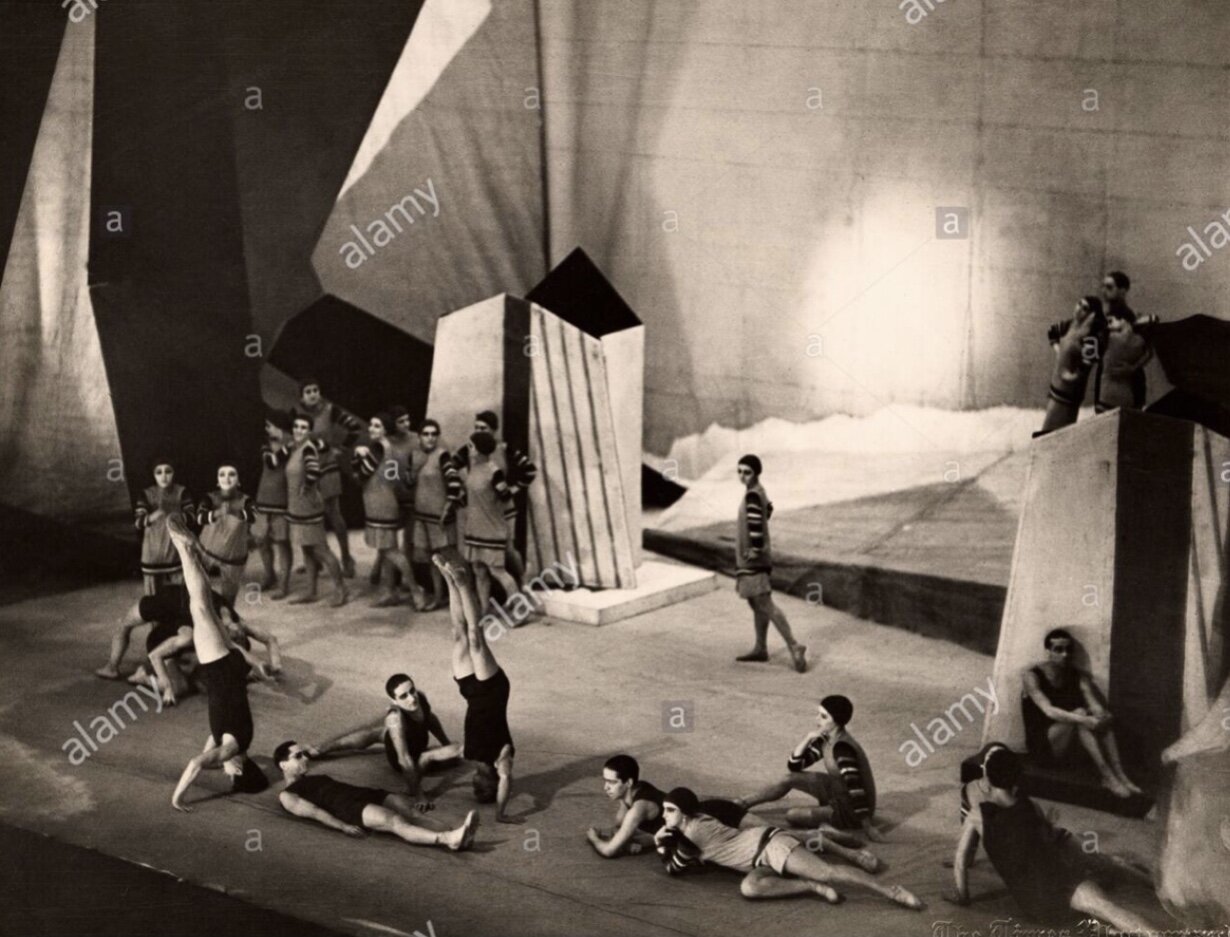

44: Bronislava Nijinska’s ballet “Le Train bleu”.

45: An ensemble in the 1935 film of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, choreographed by Bronislava Nijinska.

46: Nini Theilade as a solo fairy in Bronislava Nijinska’s film choreography in the 1935 film “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

48: Bronislava Nijinska with the leading Royal Ballet dancers of her 1964 production of “Les Biches”. On the sofa, left to right: Robert Mead, Svetlana Beriosova, Nijinska, and David Blair. Standing, left to right: Keith Rosson, Georgina Parkinson.