David Gordon (1936-2022) speaks of Merce Cunningham, James Waring, Valda Setterfield, Paul Taylor, Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, and more

David Gordon - Interview about Merce Cunningham, and much more, with Alastair Macaulay, January 21, 2019.

This is a slightly abbreviated and clarified version of David Gordon’s 188-minute interview with me. Any researchers who need a fuller transcript are welcome to apply to me.

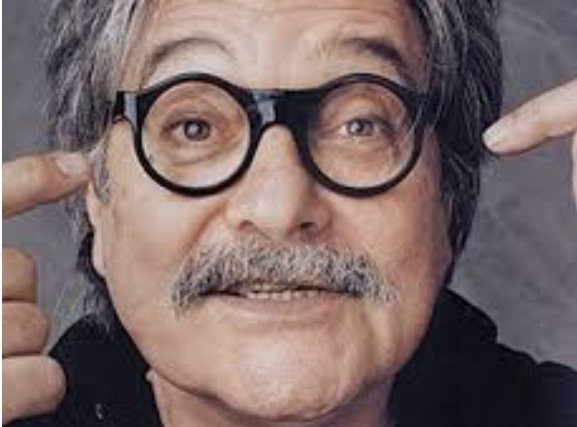

I first met David Gordon (1936-2022) and his wife Valda Setterfield in 1980, in London: they were in the audience for a panel discussion about collaboration or independence between dance and music featuring Merce Cunningham, John Cage, and others including myself. (Gordon, from the floor,asked why Cunningham, though teaching his choreography in silence, used live piano and musical phrasing for technique class.) Over the years, I met them, both as a couple and as individuals, on both sides of the Atlantic; we had friends in common, notably the critics Arlene Croce and David Vaughan. I especially remember a 1985 conversation after a Trisha Brown performance, when Setterfield, Gordon, and Arlene Croce discussed who had been the “ballerina” of the Merce Cunningham company; it was then I learnt of Gordon’s abiding fascination with the dancing of Viola Farber. I also observed and reviewed Gordon’s dance and theatrical creations, many of which were performed in London. I meanwhile became aware of the long association that Setterfieldhad had witb Cunningham, as student, as company dancer, as trusted friend and colleague, and as technique teacher.

Gordon and I were not close friends. Years would pass without any communication, though with Setterfield I kept in touch more often – she came to London at my invitation for the Royal Academy of Dance’s 1999 “Fonteyn Phenomenon” conference. When I moved to New York in 2007, Gordon and I saw each other occasionally, but kept a polite distance while I was reviewing his work. He never referred to my reviews of his work – I did not expect him to – but, to my surprise, in 2014 he made a point of thanking or congratulating me for the critical attention I had given to Cunningham in the New York Times: he felt that I, writing in Cunningham’s final years, was the first big-readership critic who had written of Cunningham with sympathy and understanding (“Anna <Kisselgoff> couldn’t get Merce because he wasn’t drama, and Arlene <Croce> couldn’t because he wasn’t musical. But you got it.”)

In January 21, 2018, a few months after the death of our old friend David Vaughan (much closer to Setterfield than to Gordon), Setterfield and Gordon invited me to dinnerin their Lower Broadway loft so that we could toast him. It was only then that I realized that Gordon’s experience of Cunningham predated his meeting Setterfield, and that the choreographer James (“Jimmy”) Waring, who was in Cunningham’s orbit throughout the 1950s,had been a more crucial early influence on Gordon. By this point, Gordon was about eighty; he had gout and moved with difficulty around his apartment, preferring to stay seated in one place.

Although I had interviewed and drew out Setterfield about Cunningham on any number of occasions, I did not formally interview Gordon about his experience of Cunningham until precisely one year later - January 21, 2019, again in their loft. He spoke to me for over three hours. As this transcript shows, he also spoke expansively about Martha Graham, James Waring, Paul Taylor, Yvonne Rainer, Steve Paxton, the Grand Union, his own early years, and his longterm collaboration with Setterfield. For these reasons, I publish the interview now. As Cunningham research, the interview was useful, but as Gordon self-revelation it now is remarkable, though entirely characteristicand often drawing on points he had often made before to many people.

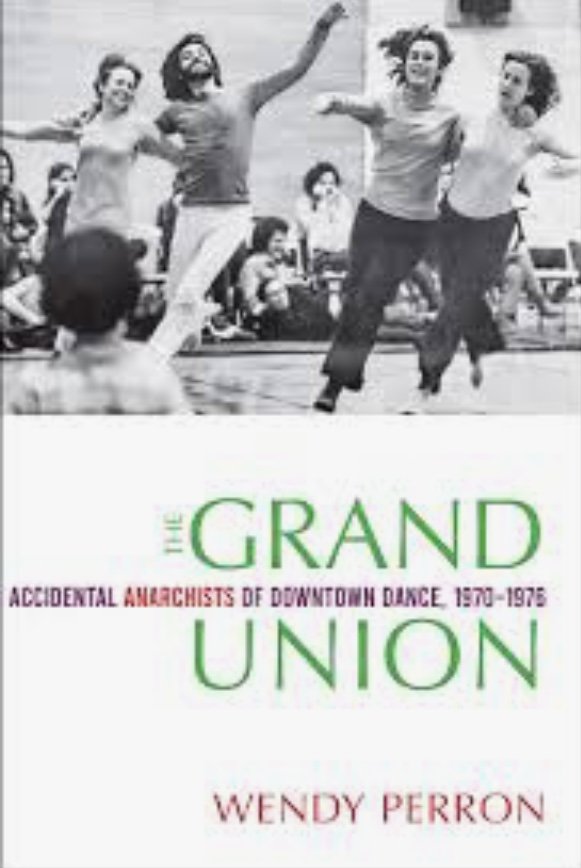

There are several confusions of chronology in this interview, unsurprising when Gordonis mainly speaking of events sixty or more years before. In section 8, he speaks of Cunningham’s Signals when he means Cunningham’s Winterbranch. Where I have been able to spot the correct facts, I have added them in parentheses. (Nancy Dalva, Cunningham Trust scholar, and Wendy Perron, historian of the Grand Union, have been invaluable.) There may be other inaccuracies I have not identified; I’d be grateful if readers drew these to my attention. Even with its errors, this interview in its broad span is a remarkable document.

As a young man, Gordon found work by designing shop windows for Azuma in Greenwich Village, and then for the Azuma chain, for many years, earning what he describes as good money. In 1957, around age twenty-one, he met the choreographer James Waring, by chance, in Washington Square Park in 1957. He soon began to work for Waring as a dancer; Waring moved in the same orbit as Merce Cunningham, with whom he began to take class, probably in 1957. Although Gordon here describes a rehearsal of Cunningham’s Minutiae (1954), that was probably a 1957 rehearsal of that work. Certainly he saw the November 1957 world premiere of Cunningham’s Polka (Picnic Polka); certainly – it eventually emerges here - he had a Cunningham scholarship in 1958 with which he attended the 1958 American Dance Festival at Connecticut College and saw the world premiere of Cunningham’s Antic Meet there, something to which he and Setterfield often referred in later years. At some point, perhaps around 1959, he realized Cunningham would not take him into his company. He did dance in Waring’s company; he had met Valda Setterfield in 1958, when she, new to the United States from her native Britain, was dancing for both men.

It also emerges from this interview that Gordon watched Paul Taylor’s 7 New Dancesin October 1957. He saw two 1956 Taylor dances, 3 Epitaphs and The Least Flycatcher, though possibly later than 1956. He seems to have watched most of Taylor’s subsequent early work until at least 1961. In March 1958, Gordon attended Martha Graham’s season at New York’s Adelphi Theater, starting with the world premiere of her Clytemnestra.

In 1960, he made his first duet for Setterfield and himself: he went on making dances for her (often duets with her) until at least 2020. They married in January 1961. That August, she and he both danced in Montreal, he in Waring’s company, she in Cunningham’s (including the world premiere of Aeon). Setterfield soon left the Cunningham company to give birth to their son, Ain Gordon. In 1962, Gordon became a founding member of the Judson Dance Theatre in 1962; this continued till 1966.

In 1965, Setterfield rejoined the Cunningham company, now remaining a member until 1975. She and Gordon continued to watch most of Cunningham’s work until 2009.Gordon stopped making dances between 1966 and 1971 after one work that was badlyreceived, but he danced for Yvonne Rainer and others. In 1970-1976, he became a central member of the Grand Union, the now historic improvisational dance group. From 1971, his own work, often with his Pick UpPerformance Company, became increasingly widely presented around the United States and other countries. In the 1980s, he made commissioned works for two British companies and for American Ballet Theatre.

Gordon’s tone in this interview was often vehement and passionate, though also often naïve. But he spoke much of it with a smile and a twinkle. I record much of my own laughter, but often – not always - he himself was close to laughter while speaking. He mainly spoke quietly, sometimes slowly with long pauses, sometimes at great speed, and occasionally bellowing in happy enthusiasm or remembered argument. AM.

1.

AM. David Gordon, Alastair Macaulay, January the Twenty-first, Martin Luther King Day. Tell me your first encounters - or viewings - of John Cage, Merce Cunningham….

DG. I’m going to tell you that, right now, you’re doing what you’re doing and Wendy Perron is writing a book on the Grand Union <Wendy Perron, The Grand Union, Wesleyan University Press, 2020> and I have had more emails in the last four days from Yvonne <Rainer> and Steve <Paxton> and Wendy – Steve Paxton – and Wendy…. I finally wrote to Steve and said “I think you and I are talking to each other more than we have done in our entire lifetime, saying ‘Well, I remember this’‘Oh, I remember it this way’.”

AM laughs.

DG: All I can tell you about that is that, when I met Jimmy Waring <the New York choreographer James Waring>, he began to introduce me to a lot of things to see, things to listen to, things to watch, people to meet, and I was a very shy and quiet fellow who did everything I was asked to do. And so at some point I am going with Jimmy to see Merce, and I’m not sure that I’m not also going with Jimmy to see Merce rehearsal…. I know that I saw a rehearsal at some point I saw a rehearsal of Minutiae <1954> on the top floor of the Sixth Avenue and 14th St building, and heard from Merce that he had been looking out the window and watching what was happening in the street and that was what was making Minutiae happen.

And I know that I saw a BAM performance of a dance in which the - in which, very particularly, Viola Farber was wearing a unitard with big polka dots on it, and I don’t think she was wearing a bra, and her beautiful nipples and the polka dots were competing for my attention –

AM laughs.

DG: And I somehow think that the dance was called something like Polka.

AM. He certainly did Polka <Picnic Polka> around that time. We’re talking mid-50s here, 1955? <Actually, Polka had its premiere in 1957.>

DG. Yes. I meet Jimmy in the 1950s and that’s when I start. I see nothing, I know nothing, I come from nowhere and…

I have written something I could read to you that I wrote to read to you.

AM <laughing> Then you’d better read it to me!

DG: To start this, because I don’t know how truly you know how little prepared I was for everything that happened. <Laughing>

AM. Well, we never are.

It’s interesting, though – going off on a sidetrack – I’ve always heard you go on about Viola Farber. She, to you, was the Merce dancer, along with Merce, more than Carolyn<Brown>, I think. <Viola Farber and Carolyn Brown were both founder members of the Cunningham company in 1953; Farber stayed until 1965, returning in 1970 for a single season; Brown stayed until 1972.>

DG. Oh no. Carolyn was… Carolyn was a kind of miracle. She was flawless.

AM. Is it true that you nicknamed her “prima modernina”?

DG. At some point <laughing>, I made that up.

AM. <laughing> I use that often, and it’s great.

DG. Well, that’s when I began to find out that there were terms. Other people used terms about other forms of dance, and I didn’t know any of them, so I made that one up.

But Carolyn was astonishing. And could, on the highest half-toe, could, literally, take that balance and she was immoveable. There was no moment of finding it. She was in it, the moment that she touched the ground with that extended foot.

Viola, however, was – There was more - There was a kind of drama about her, and a kind of comedy about Viola, because – because she wasn’t perfect. But she was - You couldn’t – I couldn’t take my eyes off her.

And I think it was not – it was not thoughtless that, when Viola is out, Merce replaces her with Valda <Setterfield>. And there is a shared vulnerability and – simultaneously - command onstage that was that between them.

I was, I have to admit, much less interested in the guys, including Remy <Charlip>, at that point. It was those two women that I was watching. And Marianne – Preger, I think her name was - was a third woman, but she wasn’t like those two to me.

AM. She would agree herself. She’s just written her memoir, which comes out in a couple of months. She knows Merce made her look good in what she could do well.

DG…. OK. Here’s what it says. I will read quickly, and… It’s only about two pages of this. And it’s called “Equal Influences”.

“I see MGM musicals at the Loews Delancey a couple of blocks from 115 Ludlow, where we live, and Milton Berle on the eight-inch Teletone TV in our living room. I’m twelve in 1948 and Milton Berle does shtick: comic gimmicks, with songs and dances, on TV once a week, on Tuesday. Gene Kelly sings and dances, so does Jimmy Durante and Donald O’Connor and Martha Raye and Don Ameche. Carmen Miranda, Betty Grable, Betty Hutton,Alice Faye, in Technicolor movies and on black-and-white TV, all the same to me. Song and dance and comedy shtick; audiences laugh and clap; that’s what I know.

“I see a movie with a live stage show a couple of times with my aunt Irene or Yette and everyone sings, talks, and dances. And in Brooklyn College I switch from English major - I can write - to Art major – I can draw – and I meet dancers in the college dance club, mostly girls. And I’m a troll in Peer Gynt, a play with words and music. I meet actors, boys and girls, and I get the Witch Boy lead in the 1940s play with music called Dark of the Moon, where I talk, dance, and sing. Paul Newman, Wikipedia says, once played that part.

“And I meet Jimmy Waring in Washington Square Park; he says I’m a dancer. And one, two, three, I dance in his company. And he introduces me to artists and the work of artists, Merce Cunningham and George Balanchine, Laurel and Hardy, Buster Keaton, W.C.Fields films; Jean-Louis Barrault in Les Enfants du Paradis, Jean Cocteau in La Belle et la Bête, Fanny Brice recordings, Satie and Debussy, films of Lubitsch where everybody talks, sings, and dances.

“I don’t question how all these things can be. Jimmy says, ‘Look at this’ and I look. I don’t remember if Jimmy ever asks what I think. I feel no pressure. Only when he finds out I’mofficially red-green colour-blind. They say so when I’m seventeen, in college. <8.46> I remember standing in front of a Philip Guston painting and Jimmy asks me to name the colours.

“So in the late Fifties, in one week, I do part-time sales jobs, work with Jimmy, where I meet Valda Setterfield, see Merce Cunningham, or New York City Ballet at City Center, or Maria Bonitez Spanish dance or Merle Marsicano with Jimmy in the evening,or take evening Cunningham classes. I collect student dollars with Lucinda Childs. We are scholarship students. We sit at the desk and students sign in, and, after I eat Jell-O at the Automat with Valda and maybe watch the late show, old movies, in the night, or read Jane Austen in bed the first time around.

“I am not a good dance student, or a consistent student. I disappear. I don’t love taking class: not the social situation nor the regimen. I am not good at regimen. ‘This is when we do this. Now, this is when we do this next.’ Even now, if I’m the guy who says this is what we do next, I want to not do it. Also I am self-conscious and vain. I have no training before college before I am seventeen. I’m not a good enough dancer. And I hate showing everyone, especially Merce, how not good I am.

AM laughs.

DG. “When I take Cunningham class in the Fifties, exercises and floorwork across the floor are done to live piano. I believe it still is. Melodic, recognizable piano music, responding to the invented movement phrase. We dance with the music. No resemblance to the music the Cunningham dancers dance to in performance.

“It never occurs to me to question. I remember thinking in Cunningham studio performances, with Meredith Monk as guest music maker at Westbeth, and Meredith singing, ‘Will the Meredith sound change the Cunningham movement?’ It didn’t seem to, to me. Later, I asked Valda, who is dancing with Merce, ‘Did you hear the music?’

“When Jimmy makes Dances before the Wallin 1958, Valda and I are in it. We rehearse with no music. Jimmy builds a music collage we don’t know, which includes Mahler and Fanny Brice, etcetera. And I discover, in the first rehearsal, one piece of music might endand another might begin in the middle of what I’m doing. I don’t change how I do what I do. Will it matter? I consider, but I don’t ask about it.

“In the Cunningham pieces, when a radio is used, and in the orchestra pit, switching stations happens, does hearing something other change what I see? Sections of movement material change character – or do they?

“Years later, I make a single movement section danced in the first work of the evening and in the last, in different costumes, to different music. I don’t talk about it with anyone.

“In these last years, I feel a great freedom to change the music for any resurrected piece of material I made. Valda’s Muybridge solo was originally performed to no music. Later performed to Philip Glass music for The Photographer <1983>. And recently to the Bolero by Ravel, and, at MoMA <2019>, to a piano version of the Bach Chaconne.”

That’s all I wrote. But it was about what I did and didn’t understand or question, when I first encountered Merce and the circumstances surrounding it, which I didn’t know were breaking the rules of modern dance. I did not know that. And I did not know what the ballet rules were, rules of production and performance.

And when I began to find out what it said it was doing, I began to question when it was notdoing what it said it was doing.

AM laughs.

DG, Including - as I think I told you some time ago - at some point when Scramble<1967> (which is about to be done <i.e. revived by New York Theatre Ballet in 2019>), when Scramble was new, and I was seeing the first performances of it, and the curtain went up; and all the Stella <Frank Stella> objects were on the stage: the first thing the dancers did was move all of them upstage and then do the dance downstage. Of all of them. And the next time I saw it, they did exactly the samething. And the next time I saw it they did the exactly the same thing.

And I saw things - Merce’s work - many times.

And at some point, with rather too much alcohol in me, at a party with Merce, I said “So why is it called Scramble if you never scramble it? I don’t understand. Why aren’t they moving those things around while they’re dancing? Why aren’t they -?”

And Merce said “They <the dancers >don’t like them <the Stella objects>. And they’re afraid they’re going to run over their bare feet. And so they want them out of the way.”

“What do you want?”

He said, “Well, I don’t want to fight with them.”

AM. They being the dancers?

DG. The dancers.

The next thing that happened is, there was a full-page ad in the New York Times, which we used to get every day. And the ad was for BAM, where there was a series of things they were doing, and one of the things in the ad was an evening in which they were going to do Scramble three times. It’s what it said. And the next thing that happened is there was a notice sent out that that evening was cancelled.

AM laughs

DG. And that was the story of Scramble.

So I saw Merce from the same early time that I saw Balanchine’s work at City Center, the same time that I saw Katy Litz doing solos, which were astonishing, and Merle Marsicano making very peculiar work. And at some point Merle Marsicano asks me to come and work with her. And I attend a rehearsal in her studio. And all I’m asked to do at some point is to stand in fifth position, with my arms out to the side, and Merle Marsicano was somewhere over there, doing Merle Marsicano things, and looking in the mirror, and at some point she says “I’ll have to talk to my husband about this.” And I never hear from her again.

I had the feeling that I was being hired not as a dancer but as a set piece for Merle to dance with.

But I’m seeing all of those things for the first time, and simultaneously Jimmy is handing me a long-playing record of Fanny Brice singing “Second Hand Rose”, which is the first time I ever hear it, and simultaneously taking me to Carnegie Hall to hear Mahler’s Something Symphony. And everything is happening at once, and I am seeingsimultaneously Edwige Feuillère in French film and I’m seeing Jean Cocteau films and I’m seeing every Laurel and Hardy comedy that ever was made. And Jimmy just – he hands them all to me equally. And he doesn’t ask me to tell him what I think of them. Or I sit quietly. He introduces me to people.

I am not asked by anybody to do anything but look good. And I am young enough to still look good.

2.

AM. You described something like this climate when I came here for dinner a year ago. And you said there would be these downtown parties where the modern dancers would all talk to the other modern dancers about modern dance and the ballet dancers would talk to the other ballet dancers about ballet and there’d be two men present who could talk about both modern dance and ballet as if they were both equally interesting and reasonable and about the latest movies and the latest exhibitions: they were Jimmy Waring and David Vaughan. In that kind of climate, and indeed among the bigger aesthetic spread you’re describing via Jimmy Waring, how does Merce fit in, for you? Whether socially or as an artist?

DG. Well, first of all, I question whether I said exactly what you’ve just said, because I don’t think I attended very many parties in which the uptown people and the downtown people were in the same space at the same time.

David Vaughan – whom I did not know very well, at all – and who did not invite my knowing him better – in fact, it took some time after I had married Valda, that he seemed to forgive me for that, and I became included.Most of the time, if I answered the telephone, I said “Hello?”, he said “Hello David, it’s David” and I said “You want to talk to Valda?” <laughing> and gave her the phone.

The parties that I went to were mostly, if I went to any of the parties, were mostly the downtown people - and they never did go uptown and they never did to the ballet and they never did go to the theatre, the musical theatre or not.

I had never been to the theater. But I discovered in college – I am in college when I discover that you could go to a Broadway theatre and buy a standing room ticket for two dollars. And so I begin by myself, without telling my family what I’m doing – I’m still living at home at that point - I just go and see Broadway plays. But I can’t talk to the dancers that I know about them, because they have no idea who I’m talking about or what I’m talking about and they’re not interested.

I remember very clearly coming back, dancing with Yvonne by that time, I’m married, and dancing with Yvonne, so it’s after ’66. and I remember coming back to rehearsal after I had been to see – I had been to see Rosalind Russell in Auntie Mame and Bea Lillie in the same role. I can’t imagine how Bea Lillie arrived at what she did in relation to what Rosalind Russell did. Rosalind Russell was very glamorous, Bea Lillie braided her boa into her hair, stepped back, I remember distinctly watching her step backward into backless shoes.

Both AM and DG laugh.

She was amazing. And I was saying “How is this?” People do the same thing but it isn’t the same.

And I also went to see Carol Channing - I first went to see Ruth Gordon in the non-musical version of The Matchmaker, and then I went to see Carol Channing in The Matchmaker and then I saw Ginger Rogers replace Carol Channing in The Matchmaker. And I came back to tell Yvonne Rainer and Steve Paxton,“You have to understand what’s going on onthat stage because you know that song, you know what that person did with that song, and how it meant in that scene, and now you’re listening to this – I mean Ginger Rogers is just amazingly uninteresting in this…”

AM: You never knew the Grand Union /Judson people talk about these people! How funny. Go on.

DG. So that is what I was comparing. That is what I was doing.

The parties that had the most subtle, little, fine range of things were the Ruth Sobotka parties, in which the New York City Ballet people were there but also some of the people that Ruth knew as artists. And that included Jimmy and me and… <Sobotka’s parties almost certainly also included David Vaughan, who was her good friend with an apartment in the same house. At various points in the 1950s and early 1960s, the house at 222, East 10th St – where Vaughan went on living until 2016 – contained Sobotka, her husband Stanley Kubrick, Vaughan, Setterfield, and Gordon.>

So that’s where I heard or found out. And I had not yet met Arlene Croce. <Croce and Gordon met in the late 1970s on the dance panel of the National Endowment for the Arts.Having reviewed some of his work, she then wrote an extended New Yorker profile of Gordon and Setterfield in 1982, her first profile for that magazine.>

At which point, social situations all happened at the ballet, at intermissions, and I suddenly found myself in the midst of people talking very seriously and satirically about what was happening that evening in whose performance. And I - in all of those situations - I never opened my mouth.

I, for several years, when David Vaughan introduced Valda to Ruth Sobotka and Valda moves into Ruth’s apartment and Ruth and Valda have a conversation - I hear later, many years later - a conversation in which Ruth says to Valda “And are you interested in meeting some men?” And Valda says “Well, I don’t know really, I just arrived” and – she says she said – and Ruth says “Well, there’s somebody that David – that Jimmy Waring keeps bringing here. He’s really quite an attractive fellow. He never talks to anybody. And he only eats bread and mustard.”

AM laughs.

“But I think he’s interesting. And you might want to meet him.” And I tell Valda afterwards, when she tells me this, the only reason I only ate bread and mustard, was I didn’t know what anything was on that table! I didn’t understand what you did with what that was! And I recognized bread, and I recognized mustard. So I put some mustard on a piece of bread and that’s what I ate.

I talked recently, on tape, to two of the curators at MoMA. I was asked to come in and make an audio tape. And they asked me some questions. And he - I think his name was Thomas <Thomas Lax> – he asked me some questions about how I met John and Rauschenberg. I met Rauschenberg and Bob Rauschenberg and Jasper because Jimmy introduced me to them because he took me to shows at the Stable Gallery. And I saw all those early shows that they were doing in those places and somehow or rather when – I become a scholarship student for Merce, with Merce, at Connecticut College at the American Dance Festival, the year he makes Antic Meet.

AM: ’58.

DG. I am in a room, it is relatively dark, sort of like schizophrenic dreams in movies. Sort of dark, and Rauschenberg is there and so is Jasper and so is Merce and possibly Cage is there, and they’re not talking to me, I’m just there. And I hear them, and they’re talking about Jimmy. And they’re not comfortable with his camp material.

AM. Would that <“camp”> have been the word then?

DG. I don’t know if that was the word, but they were talking about the things that I thought amazing about Jimmy. I thought the fact that Jimmy took me to see Lyda Roberti - do you know Lyda Roberti?

AM. I know that Ginger <Rogers> parodies her in one number, and I know –

DG <parodying Lyda Roberti or Ginger Rogers’s parody of her>. Hhhhot! You have to be Hhhhot!

<AM laughs>

DG. Jimmy took me to see W.C.Fields, that very surreal movie called Big Broadcast of Something <Big Broadcast of 1938>, and Lyda Roberti is in it, and people are doing things on the radio but it’s on television and they’re in a plane and they fly a parachute and they fly in a plane and they’re in a foreign country and it’s the most amazing surreal movie and I have never seen anything like it. And Jimmy is like that; everything about Jimmy is like that. We’re at a restaurant with Jimmy and he insists – he never eats anywhere, he never ate before, he insists that for some period of time the only thing that you can possibly eat is this and something for this period of time the only thing you must never eat is that. <Laughing>

AM. And it also sounds very David Vaughan to me. Was John Cage there?

DG. I think John was there. And what I was hearing was not good about Jimmy.

And the guy at MoMA, when I finished saying that, said something - And at some point I stopped the MoMA taping and said “Wait a minute. I think what you just asked me is: ‘Were Rauschenberg and Cage and Jasper Johns - did I think they were uncomfortable about Jimmy because he was the only one who was allowing himself to be ‘out’ and they were having to hide? Did I think that?’”

And I said “I don’t know why you asked that, but, if that’s what you’re after in this interview, I’d like to stop it now, because I had no such experience.”

“I had no idea; I asked nobody about what anyone’s sex life was or who was making choices about anything, and I had no idea that there was something called ‘out’ and something called ‘in’. I did not know any of that at that period of time.

“I found out a whole lot, in a lot of dressing rooms, in dance belts, in front of a lot of people undressing I never thought to undress in front of in all my life, I found out a lot of things. But I did not know that then, and if that’s the sort of slant that you want to have here, I don’t want any part of it. “

And the fact is I just didn’t get any of that. At some point in time, I fully admit, I agreed to go and visit Remy Charlip and Nick Cernovitch, who were together. I’m not sure if I knew how together they were – but they were together, and they lived together, in a loft space, on Suffolk Street, on the Lower East Side. Now, in the way that all of this is nuts, my aunt Irene lived on Suffolk Street, about three buildings down, and there were no lofts there, there were only buildings that were inless good condition. And they had no glass in the windows in their loft, they had clear plastic up on their windows. I had never seenthat before. And at some point - we were there for some time - they said “Do you want to stay over?” And Jimmy said “Okay.” And it looked like there was one bed. And we were both, Jimmy and me, going to sleep in that bed. And I thought “Okay?” I took off my clothes and got into bed in my underpants. And Jimmy kept every single thing on that he had come in and got into bed at my side and turned his back to me, and we went to sleep.

And Jimmy liked very much to kiss me goodbye when we left each other. And he bought me many presents. And then, when Valda came, he did exactly the same with Valda. And I think when Valda told him she was going to marry me – the same reaction - Nobody thought it was a really good idea for Valda to marry me!

AM quietly claps DG.

DG. Yeah.

3.

AM. You talk about being a Cunningham scholarship student in ’58. Had you already taken his class in New York before going to Connecticut College?

DG. No. I had taken no dance classes before I began to take class with Merce. <At this stage of the interview, Gordon’s chronology is imperfect about this period. Later on, he confirmed and established that he had begun taking classes in 1956 or earlier.> At some point after I started to take class with Merce, Jimmy at some point convinced me to go to the old Met and take class, ballet class, I can’t remember the name of the man was teaching the class, because I had no training. I was in a class with ten fifteen-year-old girls and I felt like a fool – and so I didn’t continue to do that.

This all coincided with Around the World in Eighty Days, the Mike Whatever His Name was movie. <This film, produced by Michael Todd, had its premiere in New York, in October 1956..>

AM. David Niven and all of that.

DG. Yes. And Elizabeth Taylor was married Mike Todd, Elizabeth Taylor was married to Mike Todd, and there was a huge party to celebrate the opening of Around the World in Eighty Days in Madison Square Garden. <Here, Gordon is surely referring to the spectacular party thrown by Todd at Madison Square Gardens, attended by eighteen thousand people on the film’s first anniversary in October 1957.>And because I was in this class, there was a folk dance we learned to do and we all had to go and do it in Madison Square Garden and we had to stay in one of the <??s> and follow the elephants in –

AM laughs.

DG. And I did that as well as everything else I was doing because it was the next thing that happened.

And I questioned when I questioned. To myself. I never even had a conversation with Jimmy about it.

I questioned the fact that the Cunningham-Cage creative circumstance seemed to radically reimagine the relationship between music and dance from everything I knew from movies or television - and, in that reinvestigation, seemed to arrive at as rigid a relationship to it all as the relationship they were questioning.

And the only time that some other kind of thing happened was the - when Merce was making the Satie piece, which they were actually going to dance to the Satie piece – and then the Satie Estate said they couldn’t - so John made the second-hand score called Second Hand, which still – it was written in relation to what they had made physically happen to the Satie music. I didn’t really understand that.

<Gordon here conflates various threads. In 1943-1944, at an early stage in Cunningham’s love affair with John Cage, Cage had been rapturous to discover Erik Satie’s cantata Socrate, while Cunningham had made a solo, Idyllic Song, to the first of its three movements. In 1969, Cunningham prepared the other two movements in note form, and re-studied his 1944 solo, but was informed by the Satie Estate he was not permitted to use his two-piano arrangement of the score. Cage therefore composed a new score, using the structure and phraseology of the Satie; he named his score Cheap Imitation, while Cunningham named his dance Second Hand, which had its stage premiere in January 1970.Gordon speaks as if Cunningham had created the work with the dancers before he and Cage decided to fit it to a new Cage score, and that the dancers had learnt it to the Satie music.Not so. Cunningham taught the movement to the dancers in silence. At the time of the premiere, none of them knew that he had based it on Satie’s score, though a few began to learn of its connection to Socrates.>

4.

DG. The thing that I think I was most interested in - and I thought it was real, and I wouldn’t have been able to talk about it philosophically - was that Merce rearranged the focal point of visual expectation. I had a background in visual art because I became an art major in the second two years of my college, and so I was looking at the way Renaissance art is made – where the center is, where the focal point is, how everything drops away from it, how, when something peculiarly attention-getting is happening there, something peculiarly attention-getting is also happening here. But with Merce you could not guess where he intended you to look, more than not, at it. And it wasn’t for me an uncomfortable thing, it was an adventure. And that continued.

It continued all the way through to when Merce began to be able not to do things. And it became clear that Merce could still partner. And he would come out onstage and plant himself somewhere and do things to whoever passed, but he became the center. Whether or not he intended to be the center, he couldn’t help but acknowledge that he became that center. And then when he began to use the barre - like I use the shopping cart - it was a bigger center that he set up, became he framed it, in a kind of way. At that point, I began to wonder why he was still doing it.

I came to appreciate the fact that he insisted on doing it because I had also seen that earlier Merce, who was - In a kind of way, Merce was like Viola.

AM: What was it like for you watching the Merce pieces in which Merce wasn’t dancing? And there were some from the Seventies onwards.

DG. Yeah - many of them. I was very interested in what was happening and I was no longer in love with anybody. And so it was very interesting to watch dancers I wasn’t - I hadn’t come to see the dancer, I had come to see what he <Cunningham> was doing now with this music. And sometimes I came to see what he was doing with the music and with some object that he had determined would be the physical, not set, object.

And when he was working with Bob Morris <Canfield, 1969> – there was always talk -and the talk had been that Bob Morris wanted to put grease on the floor, so that they would all be dancing in <makes squelch noise> something that’s sliding. And that was not agreed upon. And so it got to be that that light did that <gesturing to indicate the hanging vertical bar that illuminated the Canfield set as it crossed the stage> and illuminated and went back and illuminated what it did, which turned out to be a not uninteresting thing to have happened in the way Merce used the stage. That was very interesting. 41.02

When I flew to Rochester to see the first performance of Walkaround Time <1968>,that turned out to be less interesting in relation to all that had been or going to be about.Duchamp was there, and all of that was happening. But the fact is that it was not entirely dissimilar to the Frank Stella piece, Scramble <1966>, because all of those things needed to be got out of the way for people to do what they were going to do. And in fact, one of the most interesting things in Walkaround Time was Merce, taking off his clothes and putting on his clothes, in that running thing over at the side in which you couldn’t take your eyes off Merce doing that.

And once again that was, in the way that Antic Meet was - to me, to the guy who, to this person who only knew movies and televisionand - Merce was a great vaudevillian. He knew everything, he knew the style of everything that he did. So it wasn’t pastiche, it was the thing itself that he was actually doing.

I did not know the word “pastiche” until I did Shlemiel <1984-1986> and met Arnold Weinstein, who was the lyricist, who was a fabulous man and from whom I began to understand, when you are making something or writing something, it isn’t – it will get a laugh but it isn’t intended to belittle the thing you’re doing, it is intended in fact to frame it, so that it exists as an equal part of everything you’re thinking about.

5.

DG. And Antic Meet <Cunningham, 1958> was amazing to see. And at Connecticut College <where Antic Meet had its premiere>, in which Merce was not only the lowest man on the totem pole, that summer that I was there, he was a joke to the serious modern dance people, because - Doris Humphrey was there, with her cane, shepherding José Limon into the future.

AM. Gosh.

DG. Yes. All of that was happening.

Graham – Martha - was in attendance, and taught Graham class for the first week – I took Martha Graham’s class for one week! The entire Cunningham company came to watch me take Martha Graham, my first Martha Graham dance class!

AM. Was it your last week of Martha Graham class?

DG. It was my last week of Martha Graham after it was my first week! Because Martha, in the first day of teaching that class, Martha appeared in that room, in a - at nine o’clock in the morning at this class - Martha was wearing a long black dress to the floor with long sleeves. And her hair was pulled back, and in a bun, and many gold kind of chopstick things were in her hair. And she explained to the fifteen-year-old dancers in ponytails and leotards how they must be like “proud prostitutes holding Jesus in their arms” as they do a plié in second! And at some point she walked by me and pinched my ass and called me “Lamb of God”.

AM shrieks with laughter.

DG. And I thought “Well, this is really amazing! I think I’ll just do this for a while!”

By the end of that week, Martha was gone and David Wood had taken over and he was teaching us to do pliés in second while doing this to put life into our pliés. And I thought “No, he doesn’t do it for me.”

AM. You preferred being called “Lamb of God.”

Both laugh.

DG: And I stopped.

But it was amazing to be knowing what Merce was doing, to be watching what Merce was doing, to be taking Louis Horst’s composition class, simultaneously – I’m doing both of those things, I’m watching his rehearsals, I’m watching the rehearsals of everybody else,because I’m on, as part of my scholarship, I have to be on the lighting crew, so I am watching everybody get ready showing what they’re doing.

And now for the first time, I am comparing this historical material, which isn’t changing in its present mode, I am watching that happen and I am watching what Merce is doing. And it’s the first time.

The next thing I do - some time, I guess it must still be in the Fifties - Martha Graham has a season on Broadway, at something called the Adelphi Theater, in my memory. <Here Gordon’s chronological sense lapses again, though only by a few months. Graham’s Adelphi season, opening with the premiere of Clytemnestra, antedated the 1958 Connecticut College season by several months.Cunningham saw one of the early performances of Clytemnestra, disliked it, and parodied it in one section of Antic Meet, made in the following months.> And it’s the first time she’s doing Clytemnestra and she’s still dancing, in Clytemnestra, sort of being held up on either side by Bert Ross and somebody else. And I determine – since I know nothing, and I can’t figure out how to catch up with everybody - I go and buy myself a ticket to every single piece that Martha is presenting.All of it.

And I actually think that pieces like Deaths and Entrances <1943> are really interesting and pieces like Clytemnestra are really terrible. And how could that be, that this woman made that and that? And I see Embattled Garden <another Graham premiere during the 1958 Adelphi season>, and Yuriko jumping out of a tree, and making her ponytail do that. I see all this stuff!

At some point, with too much wine, at some party, I say “Okay, Merce, what happened?” <Laughing> “I mean, you were there. You were there at the beginning and you were in those things - and then this other stuff starts to be made. What is it that happened?”

And then Merce says, very quietly, to me,“Somebody told Martha she was wonderful and she believed them.”

<AM gasps. Although Cunningham privately objected to Clytemnestra, he almost never worded his objections. >

DG. And thanks. Okay.

6.

AM. How much in the Fifties, this early period when you’re taking in this whole dance scene, were you aware of the early work of Paul Taylor?

DG. Well, I was very aware of the very early work because, when I met Jimmy and I began to work with Jimmy’s people and rehearse, Jimmy and Paul Taylor shared a studio. It was on Ninth Avenue – I think on Ninth Avenue and the Fifties. And it was a studio over a used furniture store. And the fellow who owned the building and the studio and the used furniture store would get huge deliveries of used furniture and then he would sell them. So at some point you were dancing in the studio in a space this big and there were fourteen couches, and then there were ten couches and so you danced in a space a bit bigger than that. And I saw Paul Taylor pretty nearly every time I went to rehearsal. He was there.

I think he lived there, possibly, as well. I’m not sure.

Then, the first concert I was in of Jimmy’s, Jimmy asked very many artists to design costumes for everybody – and Paul Taylor was my costume person. And I was given a pair of cotton tights. And I think I had no shirt. And he had half, half-globes - and I had them on my shoulders and on my chest and my back, my head…. And then he painted my crotch. Green. With paint and a brush. And it went through my tights onto my –

AM. – groin.

DG. – Green. And I was green for some time.

And so I saw the solos at - that he did at Paula – at Cooper Union and something called Least Flycatcher, I seem to remember, perhaps I’m making that up. <Not so. Taylor’s solo The Least Flycatcher had its premiere in 1956, with Rauschenberg designs and Stravinsky music. Probably Gordan saw post-1956 revivals of that and 3 Epitaphs.>

And at some point early on, Paul Taylor, while all of this is happening and working with him, Paul Taylor is in Li’l Abner <1956> on Broadway, being one of the muscle guys. And he either fractures or does something to his ankle. And he’s out and he has a cast, so he’s around the studio more.

I am at the concert <Seven New Dances, 1957> at which he <Taylor> stands still and the tape says “It’s twenty-two seconds later. Now it’s twenty-four seconds later.” I am at that concert. And Tobi Armour’s in a sort of a Thirties chiffony dress that has a fan blowing on her dress, and she doesn’t move. And Paul Taylor is –

And I see the Rauschenberg piece with mirrors in here –

AM. The 3 Epitaphs <1956>.

DG. 3 Epitaphs. This is the work I know at the beginning of Paul Taylor. And so he fits right into this – everything that everybody’s doing – which is a bit surreal or Dada, as I come to understand, eventually.

And then, after that concert at the 92nd St Y, inwhich many people walk out <1957> - and I am now in the lobby amongst the – There’s a kind of revolution – This group of people who hate it! and this group of people who adore it! They all hate each other! and they’re shouting things at each other!

Slight digression. I am a very young fellow, the ringbearer at my aunt Irene’s wedding. And I have done whatever I have done and now they are saying “Do you take him? Do you take her?” in Hebrew, which I do not understand. And then Irene’s husband - they put a shot glass under his foot, and he breaks the shot glass, which means he’s going to be the man of the house. And the moment that that happens, the entire group of people, the entire place of people, I don’t know most of them, members of his family, everybody suddenly is killing everybody in the place. I see my grandmother’s brother being strangled! I see it happening! And people are hitting each other! And throwing things at each other! And the police come. And the police make everybody stop. And the wedding is going to be over. And I am this big, and I ask nothing, and I say nothing.

And a hundred years later, I say to my mother one day, “Listen, I have a memory <laughing> that he said ‘I now pronounce you man andwife and everybody tried to kill everybody. Am I making this up or did this happen?’”

And my mother, who doesn’t like to talk about – My mother says <mumbles> – I go “What was that?” “Well, Irene’s – our – family and her husband’s family, they did not like each other. And somebody thought that somebody said something that shouldn’t have been said about the thing that they’re now married. And so a revolution happened and everybody tried to kill everybody.”

Well, that’s what it was like on the night of Paul Taylor at the Y. I have never –

AM. So it was like that before Louis Horst wrote his review? <referring to the famous blank review written in Dance Observer by veteran composer-critic-teacher Louis Horst> –

DG. Before any of that happened. In the place! At that time, that’s was what was happening. Nothing had been like this. I had been with Jimmy to see many kinds of things, and this behavior had never occurred. And now people were really angry about – something.

AM. And it was fine by you, what was going on onstage?

DG. It was. Everything that I was looking at was, in some way, some other thing. I went to the Stable Gallery and I saw the first showing of Rauschenberg’s animal head sticking through a thing on the wall. “Who got a killed animal and put them through their ark, hanging on the wall? I don’t understand what any of this is, but that’s amazing. I have to think about that.”

Now all of this is happening. Then came the review. Whatever that meant.

And then time passed. And the next concert, which I think also maybe happened at the 92ndSt Y, had a tree in it, a set by Rouben Ter-Arutunian, and music and dancing. And it was like made by another person. And there were three pieces. <In January 1961, Taylor gave the premiere of Fibers, with designs by RoubenTer-Arutunian. But Taylor had presented other premieres in the years 1958-1960; several of them had designs by Robert Rauschenberg.>

And afterwards I am overhearing. I am not asking questions. But people are talking. And their conversation, in my memory, is that Lincoln Kirstein goes to Paul Taylor, after that concert with the standing-still, and says “If you want to do this, and to be with them, you can, that’s your choice. But it will never get any farther than this. You will just do the next thing you think of and then the next thing you think of. But you’re a really good dancer, and you’re - really good. I think you can make better dances than this.” (I am overhearing.) “And I will help to support it and to bring you to the right people.”

And that’s how he meets Rouben Ter-Arutunian. And that’s how the next dances look like that. And that’s how he gets invited to be part of Episodes at New York City Ballet. <In 1959, George Balanchine and Martha Graham brought their respective troupes together, creating pieces to Webern music, both called Episodes. They agreed each to take one dancer from the other’s troupe. Graham used Sallie Wilson; Balanchine used Taylor. Taylor danced in some later performances of Episodes with New York City Ballet; according to him, Balanchine invited him to dance the role of Apollo.> And that’s how the entire next part of Paul Taylor’s career happens, which separates him from those people he was amongst. And he goes off in that next direction.

I see some work still, for some period of time. Jimmy is still faithful.

When I meet eventually Arlene <Croce>, she is a fan of Paul Taylor because of his musicality. She is an admirer of Merce, but she can never fall in love with him because the music is not going to ever be what she wants to hear and what anybody’s doing to the music’s not going to be what she understands, but she sees the excellence of Merce as of the dancers. She just can’t love it. But Paul Taylor had this musical circumstance.

At some point, I am going with Arlene to Paul Taylor performances. At some point, I say to Arlene “I’m not going to this any more. The only pieces of his that I’m really interested in are the really weird ones: the Victorian one with the trunk and the - When he sort of gets a little darker, and irregularly comic, I get sort of interested.

“I think Esplanade is a great piece. It is in fact a kind of vaudeville like Antic Meet is. And they are - it references kinds of performance modes which are very much more acrobatic than Merce deals with, but I recognize the kind of – There’s a moment in time when people actually jump across the space and land in each other’s arms and you can imagine they couldn’t have, you can imagine it mightn’t have happened. And that’s a sort of – that’s like a circus. So yes, I think that’s terrific, but there’s an awful lot of stuff here I have no patience with.”

And so I stopped going.

And, simultaneously, Trisha is whispering in my ear “I don’t understand why she’s so interested in that hack!”

Okay. Well, I don’t know that I would call him that, and I don’t know that I’m not interested in that, but, somewhere in between here, it’s just not on my priority list of things to get to.

<Happily> Whereas I follow Fellini into the depths of those Fred and Ginger movie <Ginger and Fred, 1986), they’re not as good as Eight ½ (1963), they’re not as good as - But I will go anywhere.

7.

AM. Same decade, the Fifties saw the birth of what we now call the Theatre of the Absurd. That’s Beckett, Ionesco, Pinter. Not at all unrelated with what – some of what you’re doing. When were you first conscious of it? And do you see a parallel sensibility to Merce? Or indeed to yourself?

DG. Okay. First Beckett I ever see, on Fourth Street, where New York Theatre Workshop is,there were some basement theatres. And I see The Chairs <Ionesco> in one of those theatres. And I see Beckett for the first time, there. I don’t remember which Beckett. I know I saw Chairs there, I remember the room getting fuller and fuller of wooden chairs in that basement. I know about the Theatre of the Absurd - I think I’ve come home. I feel like I am now in a situation in which I understand everything that’s happening. I understand conversations -

The moment in time that I see Pinter in New York – I can’t figure out how this is working. Then I marry Valda Setterfield, and I arrive in Britain, Westgate-on-Sea. And I go to have tea in Valda’s aunt Helene aunt’s for tea, with Valda’s mother and her aunt Helene and her aunt Cissa. Cissa runs a garage <pronouncing it with stress on second syllable>, garage <with stress on first syllable>. And they’re offering me things. And they’re asking me questions. “Are things as dear in New York as they are here?”

“Well,” I say, “I’ve never been here before, so I don’t really know how they’re working but certainly I think probably my mother thinks that things are more expensive than they used to be.”

“Would you like some more tea?”

“No, I think I’ve had had enough.”

Silence.

“I was wondering. Are things as dear in New York as they are here?” And I’m sitting there, thinking “I now understand Pinter.”

Both laugh.

AM. But Beckett and Ionesco just felt like New York, your New York.

DG. The first thing I did for my new kid – our only kid in the world - I found that Ionesco had written three children’s books and I bought them all and I read Ionesco to Ain at the age of – something. It all - This was the surreality that Jimmy’s work had suggested all along. The something that suggested human complex relationship between people and the circumstances that surround them. And that made all the sense of everything in my life that I had never been able to quite figure out, “What – What is being not said here?What…?”

I think I may have told you - at some point - I’m eleven, something like that – I live across the hall in the tenement on the Lower East Side from my grandmother. We are here on the back of the building, my grandmother is on the front of the building, on Ludlow Street, on the Lower East Side. And the doors are always open. Because the aunts and my mother and my grandmother are always – I have all these women in my life. At some point, my grandmother comes in and says, in Yiddish, to my mother, she needs me. And my mother says, to me, in English - although I have understood what my grandmother is doing -my mother says “Your grandmother needs you. Go next door.”

And so I close my book, and I put it down,and I go next door. And my grandmother, when I come in, says “Sit over there.” And I go and sit over there.

She locks the door. And she sits down and hands me tweezers. And she turns on, before that, the Yiddish radio station, so I can listen to Seymour Rechtzeit <Rexite> sing “Ich hab’ sie fill verlieb.” “I love you too much.” And I am sitting there with the tweezers in my hand wondering what is going to happen next.

And my grandmother moves closer and says <indicating his chin> “You see these hairs? I want you to pull out the hairs.”

Gordon laughs.

Okay. Is this Ionesco?

Both laugh.

What is this? What do you make of this? And my grandmother has clearly locked the door because she doesn’t want us to be interrupted, she doesn’t want anyone to see this happening. And she has in fact white, very powerful hairs,and black, very powerful hairs, and it is my job now to pull out the hair. And she’s saying to me, <shouting> “What are you waiting -? Don’t be a scaredy-cat!”

AM. Oh how funny. <Laughing.>

DG. Okay. Well, a whole lot of my life is like that. Things that can’t be – I discover, as I become, as I attempt to become more available in school, to people, if I say, casually, the thing that just happens in my house, everybody stops, they look at each other. I’ve just said something odd.

Okay. Maybe you shouldn’t talk about what happens in your house.

AM laughs.

Well, Ionesco and Beckett are focusing on what couldn’t possibly happen, happening, in some framed circumstance, which couldn’t possibly be framing this thing, but it is.

And The Chairs – More and more furniture is filling the space – It’s getting to be you can’t get from one side of the space to the other because of what’s coming into it.

Well, at holiday times, I don’t remember particularly which time, possibly, I don’t remember, my grandmother and my mother, lived next door to each other, made gefilte fish and pyrogen and -. They made enough for all the sisters, so the sisters could all come and take home, to their houses, enough for the entire week of meals. And so the five rooms of our house, every surface was covered in pyrogi, everywhere. You couldn’t sit down anywhere. And my grandmother had a huge bowl of raw fish. And she was chopping the fish. And at some point she said “Here”, and put a finger in the fish and put her finger in my mouth and said, “Does it need salt?”

Both DG and AM chuckle.

Ionesco? What could be – What could I find odd?

Laughter.

AM. For me, what you are talking about, with a few extensions, is Cunningham-Cage dance theatre, too. Do you agree?

DG. I do! I think that when I saw the equivalent in what I was hearing or what I was seeing, I was - That was when I was in love.And when I saw something that suggested the equivalent but didn’t reach for it or get there, I was less in love.

So when I saw the piece, Signals, when I saw Signals for the first time, on a programme shared with Anna – near Lincoln Center or at Lincoln Center – paired with two other choreographers, not any like Merce – and the audience was there to see them, and Signals was going to happen and we didn’t know what was going to happen. <Gordon here means not Signals but Winterbranch, which had a single but intensely controversial performance at the New York State Theater in 1965, sharing a programme with two other modern-dance companies.>

And the curtain opened, and Signals <Winterbranch> – with black things on their faces – started in silence. And the audience began saying “Is that supposed to be music?” <imitates people talking under their voices>– babbling – and then LAMONTE YOUNG STARTED! <Shouting, then laughing to recall the notorious volume and penetrative sound of Young’s music.>

And that audience, they fled, they fled the theatre. And I sat there thinking “Oh, this is – This is wonderful.”

AM laughs heartily.

AM. One must need an appetite for anarchy, I think, mustn’t one. And John Cage must be one of the great anarchists.

DG: Well, it seemed to me that, whether or not I had an appetite for anarchy, I recognized real anarchy and was so - It’s the moment that you meet somebody who will say the thing you have been thinking and would never dream of saying and they will actually say it, in front of other people - And you think, “How do they get the nerve to do this thing they know is going to separate them? Here am I trying so hard to find a way to fit in – and here are these people who are saying ‘FUCK “FIT IN”’. And I – I am taken with it.”

8.

AM: We’ve talked mainly of Merce. When were you first aware of John <Cage>? And when did you start forming thoughts both about John’s music but also John’s aesthetic, his ethos, the whole business of Zen -?

DG: I did not have a great deal to do with John, at all, because I didn’t – When John would come in and sub for the pianist, in class, in Cunningham classes, I was not taking classes regularly. And I did not have a lot to do with him. I went and heard music. I went to - with Jimmy to concerts in which there was music of Morton Feldman, music of John Cage, music of Carolyn Brown’s husband, Earle Brown, music of – So I heard various versions of things. I had not heard – I now have – early, early music of John Cage. I had not heard any of it at that time, I did not know what he was writing originally, and what he was writing against when he began to do the next thing and the next thing. So I had not a lot of information.

My son, however - At some point when it’s time for my son to go to public school, first classes in public school - I’m making a quite good living doing the display work and design work that I’m doing. They’re writing about me. And so I determine that my son must go to private school. And not public school. And Valda and I and Ain go to various downtown Greenwich Village, where we’re living: fancy private schools. And in one of them the person who is interviewing us says to my son, <soft, gentle voice> “And do you have a best friend?”

And my son says “Yes.”

And she says <imitates sweet, gentle voice> “And who’s your best friend?”

And my son says, “John Cage.”

AM claps. DG is chuckling quietly.

DG. And that’s because at Cunningham concerts, when John is making music all over the house, he says to Ain, “C’mon, let’s go make music” and they go together and they are walking around the house, doing what they’re doing. John is showing him where to put the something. John Cage is his best friend.

At the end of that interview, I say to Valda, “Maybe he should go to public school.”

Both laugh.

DG. He went to public school, absolutely. I thought “He better meet some real people.”

Both laugh a lot.

DG. So I did not have a lot to do with John. When I did the piece called – Travelling Without – Travelling Something <Transparent Means for Travelling Light, 1986>, I went to John and asked if he would be in any way interested in - I would like to use his music – whatever he wants. And he gave me a recording of an earlier piece in which he useda classical piece of music and did what he wanted to with it. And the names of all those things are available; they’re not just in my head right now. And he also made something called Vacuum Cleaner music: which I used at the whole opening of the piece at the BAM <Brooklyn Academy of Music> Opera House.

But I don’t think he ever was interested in whatever I was doing. They both, John and Merce, were very interested in the early work of Elizabeth Streb. And they both went together to see her, I was at some performance seeing her, that they were seeing her. But I don’t think that either of them was enormously interested in anything I did. I don’t think they even came to see Valda do what I did.

So I had not a lot of relationship.

I went to see all the later things, the big pieces, with a zillion musicians all around the space.<Possibly here Gordon refers to Cunningham’s Ocean <1994>, conceived but not composed by Cage before his death in 1992, with over a hundred musicians surrounding the audience and dancers.>

9.

DG. But I did get tired of whatever was going to be the new Merce piece, whatever was going to be its visual physical stuff afterRauschenberg stopped doing stuff, after Jasper <Johns> stopped doing stuff and the guy whose name I can’t remember -

AM. Mark Lancaster?

DG. Mark began doing stuff, which turned out to be, with some great frequency, to be brightly coloured dyed unitards. When stuff started to look like that, I was less interested. And when, inevitably, the curtain opened and there were the dancers ready to do whatever they were doing and the first thing out of the pit sounded like <makes ugly electronic drill noise> Just would get –

I wasn’t like Arlene, I wasn’t offended by it - I was put off by the sameness. Unlike that Lamonte violin, terrifying terrifying sound<Gordon here is referring back to the Lamonte Young score for Winterbranch> Impossible to live through. You could get killed by that sound!

Nothing Cage did, nothing Cage, Tudor, that Japanese fellow –

AM. Kosugi.

DG. Nothing they did ever was as impossible as that. And it just seemed - I could not figure out how different the process was this time from the last time, this piece from the last piece, on the programme, because the sound was not radically - The volume of the sound, or the quality of the sound was not – There was no radical difference, whereas there was radical physical difference going still on, on the stage that Merce was making happen.

And when Merce started to do more things on the computer. I came to see a piece - French guy was in the company <Probably Gordon is describing Foofwa d’Imobilité, whose name then was Frédéric Gafner, in Cunningham’s Touchbase <1992>>. Some time in the piece, or at the beginning of the piece, he began jumping. There was a sort of wall or fence at the - upstage. And he began jumping across the stage, going from stage left to stage right. And he reached the same place in the air, every time. And he didn’t take longer to prepare, to get into the air, any time. And it was a sort of miracle that that could happen. And then I realized, if Merce is doing that on here <indicating a computer>, unless he’s programming preparation time, in fact what he’s asking for, he’s asking the dancer to do what you can make the computer do, which is not necessarily what you can make a human do, but the dancer is doing this thing that a human couldn’t do.

And I have only ever in my life seen anything that resembled that….

And it was in Los Angeles, I think UCLA, I think Royce Hall, but I’m not sure. When I’m first on the National Endowment Dance Panel.

I go to a concert in Los Angeles of the Bella Lewitsky Company. And the sixty-year-old Bella Lewitsky begins the piece by jumpingacross the stage. From stage left to stage right. And at that point I could have left and said “Okay, thank you, I need to think about that!”

10.

AM. Carolyn <Brown> always says about Merce, “He never did steps.” Merce just was in the moment and had this famous animal quality. And I would say from film that Viola was something like that too. Carolyn herself, however, says, “I did steps.” And there were a number of people throughout the decades who did steps while there was always the odd dancer who just had that animal quality.

Did it make sense to you that the Cunningham stage could contain both types? And perhaps other types as well?

DG. That’s an interesting question because, in the beginning of everything that is happening, I don’t have terminology for the difference between some dancer and some other dancer.

I begin to understand - not in relation to so-called modern dance, not in relation to the Cunningham company - I begin to understand by looking at ballet. And when Valda and I are supering with the Royal Ballet at the old Met, I begin to understand the difference between ballet dancers. I begin to understand that Alexander Grant <a vivid Royal Ballet dancer of note between 1948 and 1976> is a character dancer. And somebody else is a prince. It has something to do with physicality, with height, with stature, but it has also something to do with some kind of - who you are.

If Valda and I had figured things out in the beginning, we would have found out that the character dancer was marrying the princessand this was not going to work!

So at that point I begin to look at where I am coming from in relation to what I am discovering in the dressing room at the old Met and onstage. I am onstage holding the candelabra in – that piece about the sea and the shipwreck –

AM. Ondine.

DG. Yes.

AM. David Gordon in Ondine! The history of dance has to be rewritten! <Laughing.><Ondine, a three-act neo-Romantic ballet new in 1958 and seen in New York in 1960, was Frederick Ashton’s final three-act ballet, very much seen at the time as a vehicle for Fonteyn, though still in repertory today.>

DG. I’m in Ondine, yes. And I am standing and holding something while watching the difference between everything.

And I am – I am onstage at the entrance of Margot Fonteyn in Sleeping Beauty, and I am here to say that, as she rounds the stage, the smile that they are getting <indicating the audience>, I’m getting right there. She is onstage facing upstage as well as facing downstage. Whereas I have seen other performers, as they are up there, going <adjusts mouth awkwardly>, and now they’re going to smile for somebody out there.

So I’m just looking at the kinds of dancers who are in – who are together in a circumstance which has a narrative, which requires them to be one thing or the other, but then I am also looking at those dancers as they appear in something resembling a more abstract ballet that does not do that, in which they presumably are more themselves than they are a character. And when that is happening, I’m looking at the rhythmic – I’m looking at how they can change. How they can do another kind of thing, another kind of – stylistic thing. I am there to witness what happens as – when Michael Somes stops partnering Fonteyn and Nureyev starts. And that woman changes! She is no longer somehow as passive as she was. She is suddenly – she has a surprising, percussive - Something happens to what she is doing.

So when I am auditioning dancers to work with me, I realise that the people I chose originally to work with me – It never occurred to me to think about the difference between them, because they were all going to be me.Then, when I discover I am really crazy, because they could do things I never could do, they shouldn’t be me! I should figure out who they are! And make things happen for them! Well, then I figure out how unlike each other they are, or, when somebody new comes to audition, I say “Oh, that’s another her. Now, do you want another her? Or do you want another her or something you haven’t had before, are you looking for that? What is it, what is it you want to do?”

Karole Armitage heads into the Cunningham company. <Karole Armitage dance with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1975-1981.> She is the showbusiness version of Carolyn <Brown>.

AM. Did it seem like that straightaway?

DG. Absolutely. She was a self-consciously presentational performer. Carolyn was not ever that! Carolyn could do everything <Armitage> she could do, but she never said“Look how I can do this!” It wasn’t like that moment that – I can’t think of the name, the ABT ballerina who can –

AM. Cynthia Gregory?

DG. Yes, Cynthia Gregory! Cynthia Gregory, when she does that balance, is saying “I dare you to stop watching me to do this now.” Whereas somebody else, you can see the moment in which there is “Can I hold this? Can I hold this? Can I – Yes! I can hold this.”

AM. There’s a phenomenal film of Carolyn in Walkaround Time. And she does that extraordinary balance in relevé fourth <indicates with hands>and you don’t know how but this leg lifts off and then slowly hovers there and then comes down, but she’s not doing a Cynthia Gregory moment, you’re not saying “Wow”. You’re in some sort of strange philosophical state with her where – I don’t know how it’s done!

DG. Yeah. It’s amazing. At some point, somehow or other, I believe I’m telling the truth, but I’m not sure – we are all in Canada<1961- he is telling the truth>. And I am there to dance with Jimmy, and Valda is there to dance with Merce, and we are meeting and we have been too shy to ask if we can have one hotel room for two of us <they had been married almost six months>, because two different companies are paying for everything. But they’re doing a piece <Aeon, Cunningham, 1961> which has a new bunch of stuff by Rauschenberg; and Carolyn runs out on the stage onto arabesque relevé arabesques, and has around her waist an astonishing heavy bunch of staff which makes noise on a rope and which goes Klang! Wang! – and Carolyn is just there. It is not pulling her off her balance, it is not into interfering: it is just there. And it’s amazing.

So the women in the Cunningham company,in the beginning, the women were the most interesting difference from each other. The two men, other than Merce – Merce was the one who was that other thing - and the other two men – Remy was perfectly nice, and Bruce, I think the other guy’s name was <Bruce King danced with the Cunningham company from 1955 to 1958>. But they were not –There was no competition with those women and with Merce.

11.

AM. I have a theory that, most of the time, Merce needed one dancer in the company, a woman dancer, who was his particular friend; and he singled out that one because she was the least needy person there. And I think Valda was that friend when she was there <1961 and1965-1975>, and I think Marianne Pregerwas like that in the Fifties. Does that make sense to you?

DG. I really don’t know. And I didn’t – I was not aware –

Long pause.

Valda and I, on the twenty-eighth or the twenty-ninth of this month, will have been married for fifty-eight years. And we are having some very interesting times at this point in our physical lives, and particularly how my physical life is making me less independent. And - So we have some amounts of argument.

<Gordon is gently laughing while he says the following> And in the course of these arguments, I have said to Valda, in the course of the last six months, “I knew, for the ten years you danced with Merce, that you were in love with Merce and John and not with me. I knew there was nothing I could do to compete with Merce and John because that’s where all your attention was. And when you came home - and I was who you came home to - it was a little disappointing. And never in the course of all of that time, when you were in anything with me, when you were in anything of mine, did you ever say to me ‘This is really interesting, what you are doing.’”

AM laughs.

“‘What you are giving me to do here, it’s really interesting.’

And in fact the story that you were witness to at the Library about the Chair Piece and the car accident and the something in the – It got said in that, it got written into the script. <Here, Gordon refers to his 2017 Live Archivography, which I saw at The Kitchen, but which was based around the archive of his work that he had recently given to the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, which had presented it over winter 2016-2017 in a remarkable exhibition that he had organized. In particular, he narrated how, when Setterfield was recovering from a car accident that had affected her memory, he had made a chair piece that used the Giselle mime about “He loves me, he loves me not”. The work had begun as therapy.>

Valda had no idea what I was doing. And never once, in the course of it, said “This is really amazing what you are making happen here.” And not until now has that ever come up.

AM: You’ve been talking it through. Wow.

DG. So. The reality is that I did not know what went on there. I dd not question any of it.

You keep hearing me say “I did not question.” I did not question!

I – I asked more questions in the last ten years, than I asked in the first forty, of anybody. Because now I’m really trying to understand how something happens or it doesn’t happen. But in the past, I just assumed that was the way life worked.

Because I was a total mystery to my family. And it was clear early on that I was best off not telling them what I thought or cared about,because it wasn’t about what we were doing or how we were living <chuckling> – I wasn’t clear about anything that was going on. I was very fond of them and I knew they were fond of me. They would have done anything to help me to do anything, but one of the things they couldn’t do was understand me.

And I think that, in this instance, I accepted – I accepted that Merce –

I took a chance class with Merce and tossed pennies and did all of that. And at some point I did ask Merce, Was I ever going to get into the company, and if I wasn’t, what was he not interested in?

And he said to me something resembling “Listen, you’re too smart. You should make stuff for yourself.”

And from the very beginning, I dealt with Merce like he was a mysterious traveller from another planet. And he could do and make things that –

Long pause.

Sorry. I have no way of putting this all together.

When I saw Sunset Boulevard, the movie, for the first time, by myself, as a kid, Lower East Side, fifteen I think I was approximately, I came home and said to my mother “Who are these people? Have you ever heard of -? Who’s Erich von Stroheim? And have you ever heard of Gloria Swanson and Erich von Stroheim and -? I don’t understand what it is they’re doing and how it is they do it – and it’s remarkable! I don’t understand how I get – how I got – to have such feeling for something that was so incomprehensible to me.”

Well, Merce was like that.

I had no relationship with Merce that was like what had happened with Jimmy. With Jimmy, I had become the center of his attention. And therefore he was the center of mine, because nobody had ever taken me to be the center of their attention! And I did everything that he asked to have happen, and I went everywhere he said, and I met everybody and dutifully did what I – what I thought I was supposed to do.

And I had just studied with Ad Reinhardt. <New York Abstract Expressionist painter, 1913-1967. Unknown to Gordon, Cunningham and Reinhardt had been friends in the 1940s>And Ad Reinhardt used to apply in black jackets and dark gray trousers and work shirts and black ties and I thought I was the best clothing I ever saw in my life and I started to try to look like Ad Reinhardt. And that was okay: Jimmy was not bothered by that, but he would buy certain things for me to add to look like whatever it was he wanted me to look like, and I wear those things, and I went everywhere and I did everything and I did everything.

And at some point, we are at some performance somewhere, he and I, and on the stage is the fabulously beautiful Vincent Warren, and Jimmy says “We must go back and meet him.” <The dancer Vincent Warren, 1938-2017, studied and performed in New York in the years 1956-1961, during which time he became the lover of the poet Frank O’Hara, who dedicated a number of poems to him; he also studied with both Cunningham and Waring. He later moved to Montreal, where he became a Canadian citizen and spent the rest of his life.>

And I think to myself “I think that’s the end of me! Whatever this has been, I think it’s over!” And we go back and meet Vincent, and Vincent comes to dance with Jimmy, and I dance with Vincent and Freddy Herkow, and I watch myself not be the center of attention.