Love Letters (love emails) from Henry Danton (1919-2022)

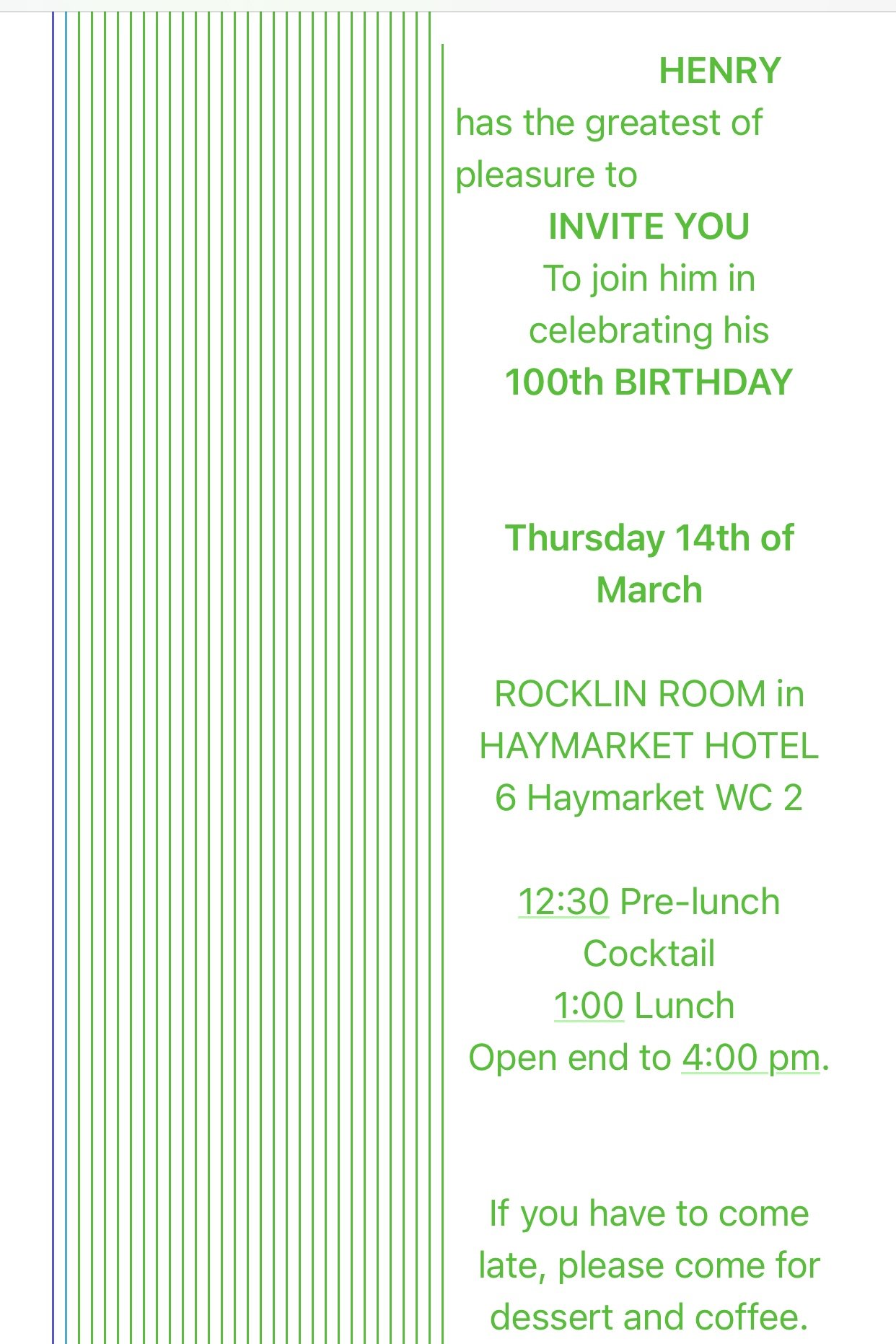

Henry Danton (1919-2022), who died on Wednesday 9 February, had a life whose shape was entirely unlike any other. Having earned a place in history as the originator of a role in Frederick Ashton’s classic Symphonic Variations (1946, when Danton was twenty-seven), he then passed - for half a century – entirely out of contact with the world of British ballet. He was widely presumed dead, whereas the other five members of the original Symphonics cast remained very much known figures on the Ashton/British dance scene until their deaths, between 1991and 2006. Yet Danton began making contact again with the British dance world from 2007 on. He began to come to London once a year until 2019, inviting friends to a birthday party (March 30) there each year; only the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic prevented him from returning to London in March 2020 and March 2021. He sent a last Christmas e-card, to a number of friends, on December 24, 2021.

Born Henry David Boileau, he took some regular ballet classes in his youth at the Espinosa school, but principally trained as a soldier at the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich, where he was commissioned with the rank of second lieutenant in January 1939, at age nineteen. He was promoted to Captain at the outbreak of the Second World War; but in 1940, he was retired from active service; he maintained military bearing until the end of his life. Danton left some vagueness about the times of his ballet studies, but he must have resumed them in the early 1940s. He joined Mona Inglesby’s International Ballet in 1943; he partnered Inglesby in Les Sylphides and the second act of Swan Lake. While there, he began to know the regisseur Nicholas Sergueyev, with whom he began to study Stepanov notation.

In May 1944, after only six months with the International Ballet, he began to dance with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, in particular being in its ranks when it moved to the Covent Garden opera house in 1946, when he was a fairy cavalier (Prologue) and a prince (Act One) in the new production of The Sleeping Beauty on the company’s opening night in its new home. On 24 April, he was one of the six dancers of Symphonic Variations, a ballet that was immediately recognised as a definitive statement of ballet classicism (and also an extreme test of stamina: its dancers never leave the stage): he partnered Moira Shearer. He danced fifteen of its first performances.

He clashed, however, with Ninette de Valois, particularly over the intimacy (partly romantic/sexual) he developed with the teacher Vera Volkova (1905-1975); he spoke of de Valois’s own academic teaching with scorn for the rest of his life. About Ashton, he had mixed feelings, although he felt that at one time Ashton began to consider him as Margot Fonteyn’s next partner, as a possible replacement for Michael Somes. He spoke of Fonteyn with admiration, though he was aware of her persona at that time as highly guarded, even anxious; probably he sensed the immense strain she had been under from years of nonstop dancing during the Second World War.

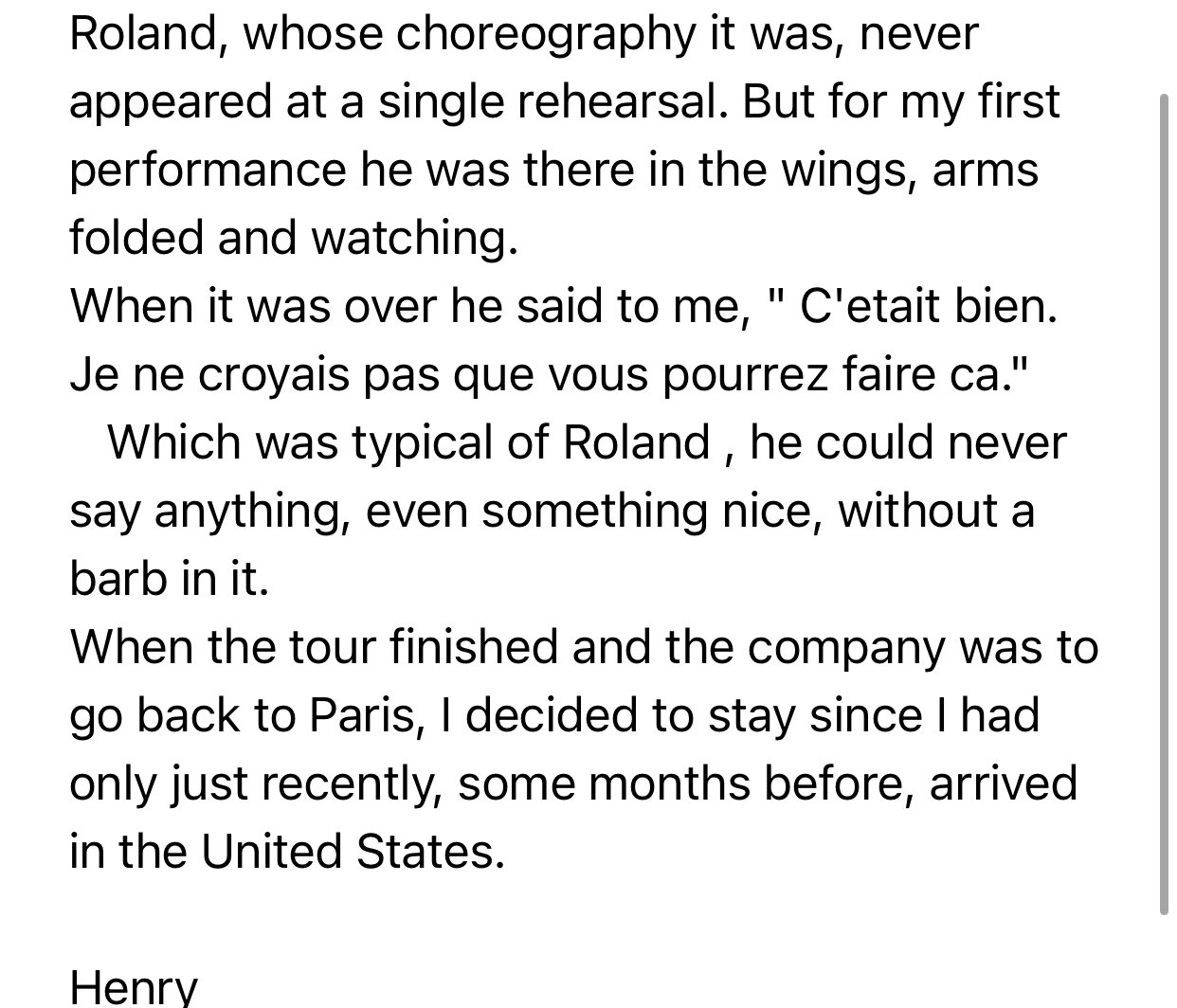

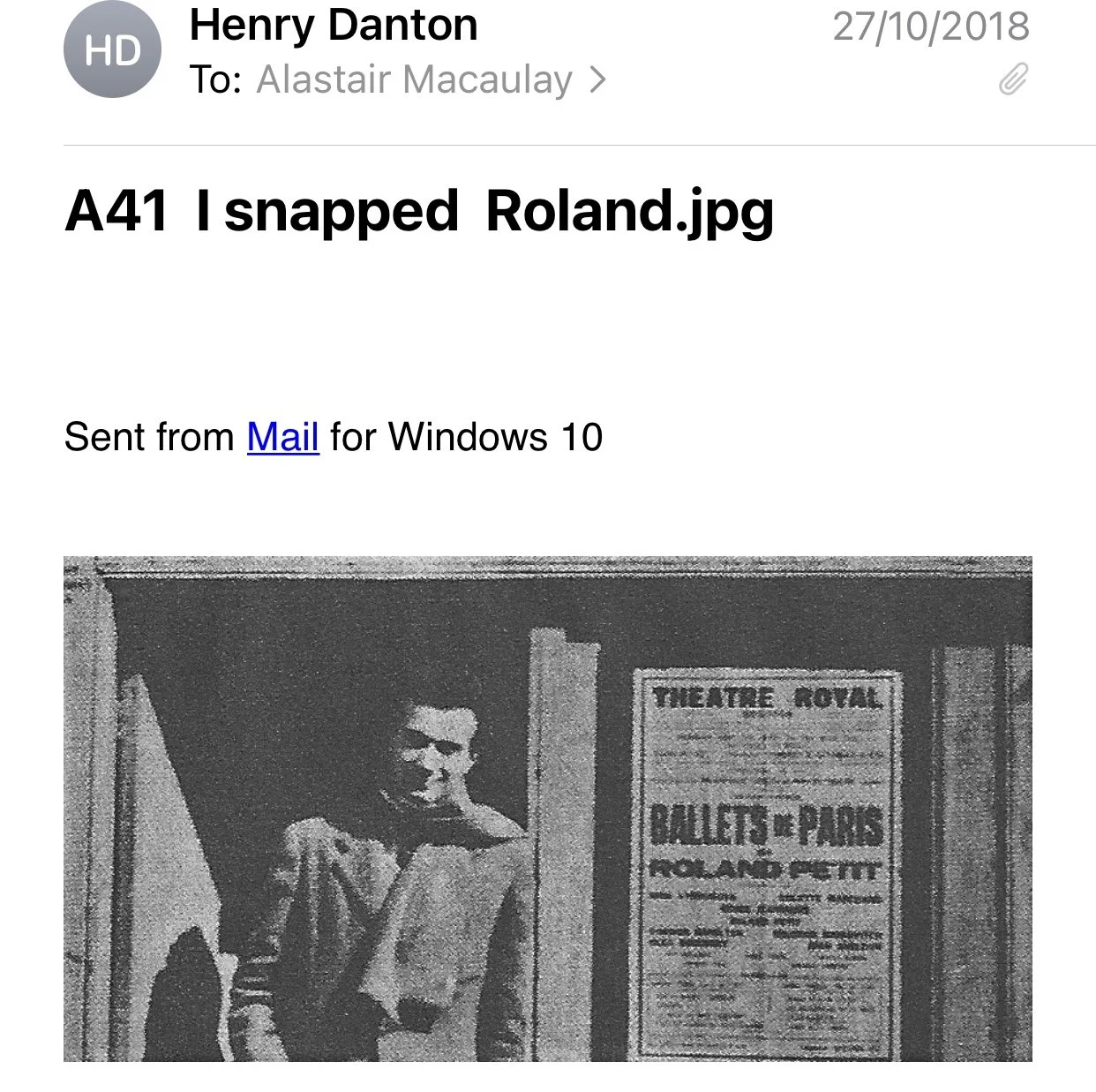

Danton’s studies with Volkova and other Russian teachers led him to ask de Valois if he could have a year’s leave to study with Russian teachers in Paris. When de Valois refused, he decided to leave anyway. Moving to Paris, he studied with, above all, Victor Gsovsky (1902-1974), whose pedagogy he admired immensely. When he returned to London after a year, de Valois would not take him back into the company. He therefore turned to Paris: in particular, he partnered the ballerina Lycette Darsonval in appearances around France and Western Europe, while she was on leave from the Paris Opéra. After this, he returned again to London, dancing now with the Metropolitan Ballet. In 1949, he joined Roland Petit’s Ballet de Paris, helping Petit with administration, and travelling with the company to New York for its long Broadway season (during which the Sadler’s Wells Ballet made its famous debut season at the Metropolitan Opera House) and transatlantic tour. Onstage, he partnered - especially in Petit’s Le Rendezvous (1945) - Joy Williams (later Joy Brown by marriage), who was already a close friend of Margot Fonteyn. Later dance work took him to Australia and Venezuela; he then returned to New York as a ballet teacher. He then moved to the American South, where he taught for the rest of his life.

His renewed contact with British ballet may have begun around 2002, when the Danish scholar Alexander Meinertz made contact with him while preparing his biography of Volkova. Another connection with British ballet began in Mississippi with Ravenna Wagnon, the former Royal Ballet principal dancer Ravenna Tucker: she became his devoted teaching colleague In Mississippi. Through Meinertz’s friend the New York critic Robert Greskovic, Henry met up with Clive Barnes and Valerie Taylor in New York in 2008, and later with myself.

In spring 2011, he came to the Royal Ballet School for its conference on Ninette de Valois. He and I, amid the many who paid tribute to her,were the only people who said any negative words about her (to the great amusement of his old colleague Julia Farron, who enjoyed hearing such heresy and could support some of his words on de Valois’s early teaching). Soon after that, Henry and I met for lunch in New York. I became aware that he was a passionate anglophile; I discovered he had already loved my English accent on a recording of a 2009 memorial event for Clive Barnes. It seems strange to think we never met again in the flesh: he subsequently sent me so many emails, voicemails, and photographs that he became more part of my life in the years when we no longer laid eyes on each other. He was especially excited in 2015, when I conducted a long Sleeping Beauty questionnaire with Alexei Ratmansky, paying us lavish compliments.

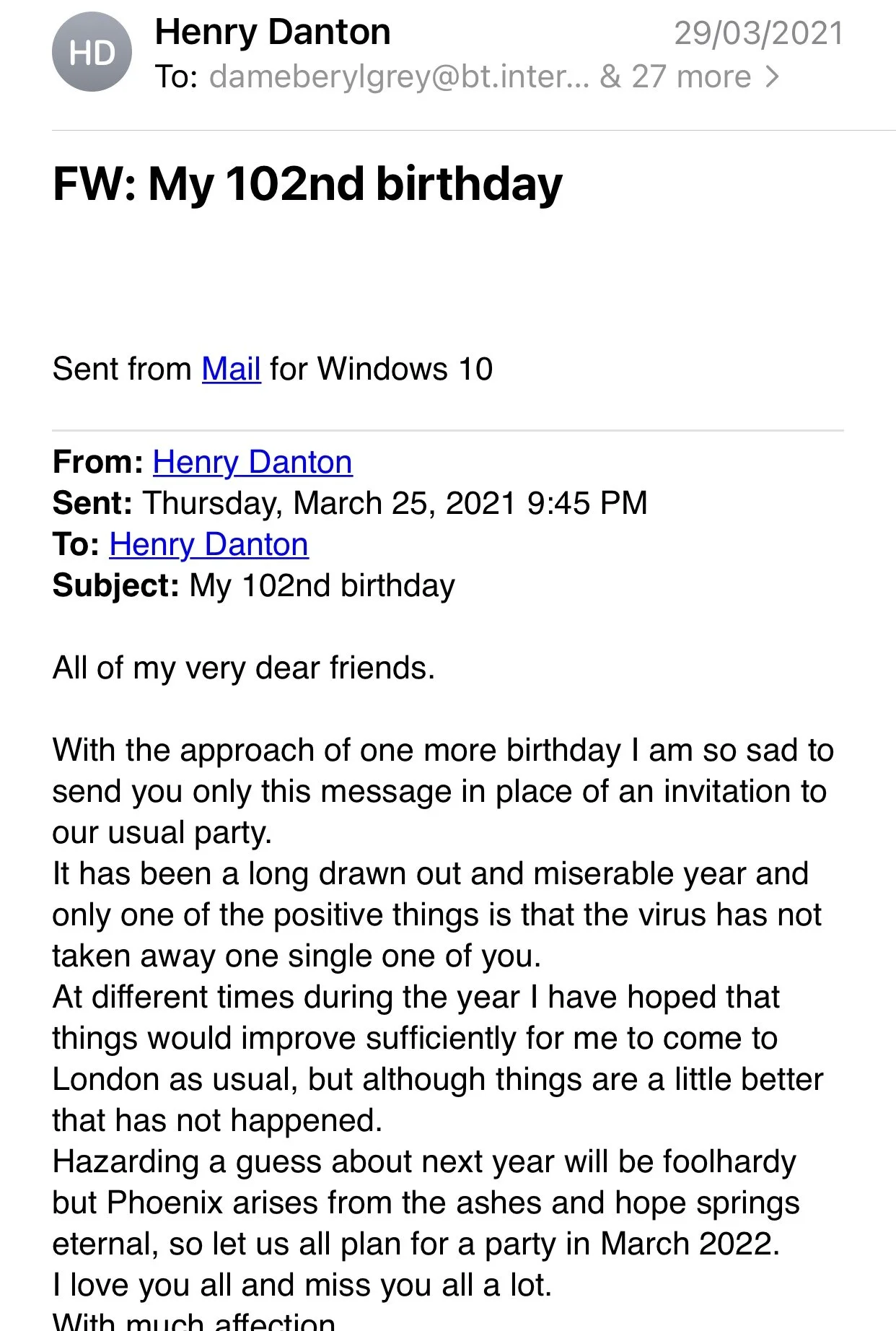

His time in the American South was fittingly rewarded soon after his hundredth birthday, when he was given the Mississippi Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts; Ravenna Wagnon was instrumental in helping to achieve this. Danton had begun to visit London at least once a year, and came for an annual birthday party there/here. I was always invited but never able to attend, but there are videos and photographs that show how many friends old and new became part of Henry’s British life. He spoke of moving back here, but that never came to pass. He entered hospital in March 2021 after a bad fall; the ensuing loss of independence was a cause of great frustration for him, but he went on answering emails. His death this Wednesday came one month and three weeks before his one hundred and third birthday. The end was peaceful. He was found sitting in his chair, a smoothie (his favourite drink) by his side, with no trauma; his heart had simply stopped.

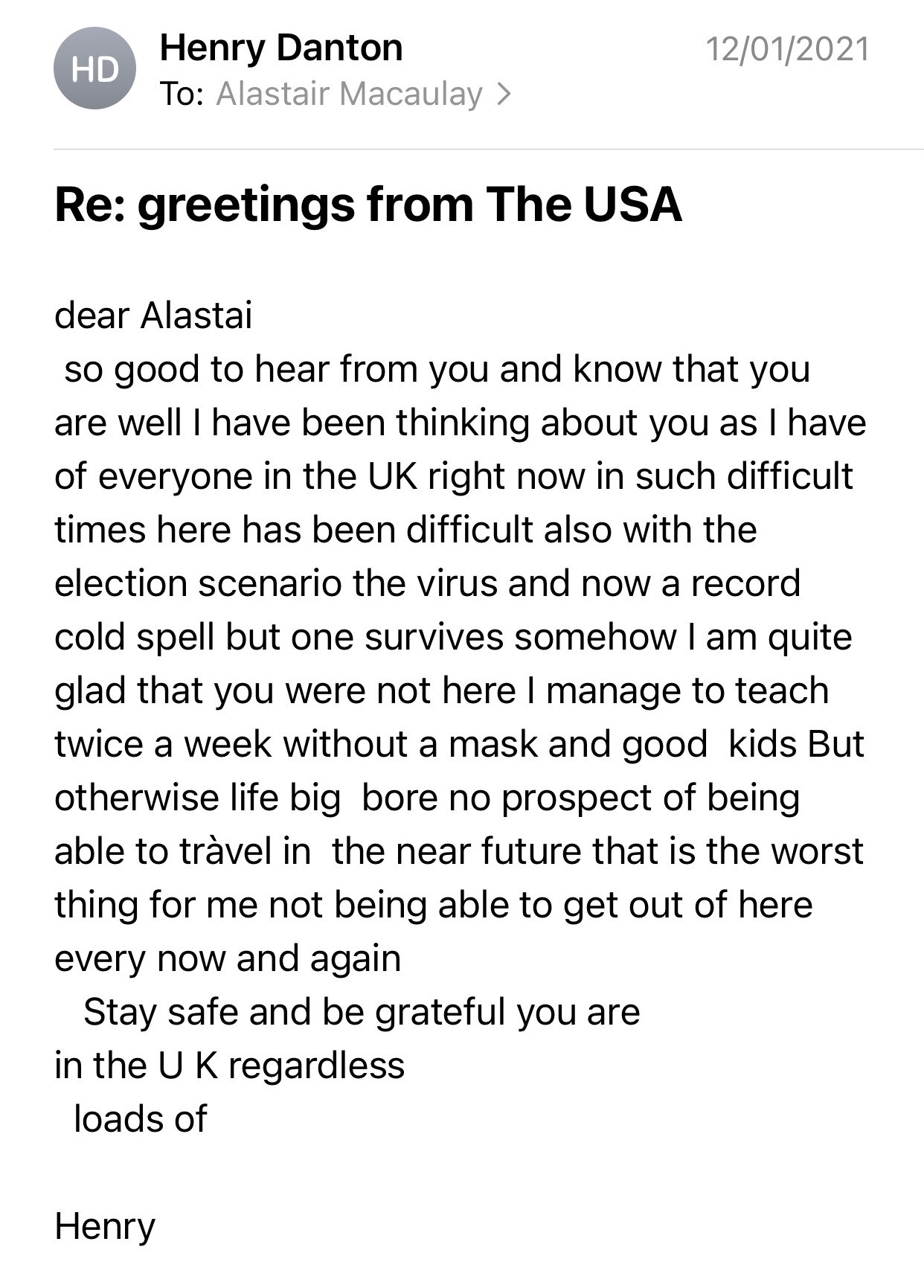

Danton was conflicted on sexual matters up to his final years. His affair with Volkova may have been his only heterosexual one. In one draft of his memoirs (none have been published), he wrote of homosexual liaisons in childhood and during the Second World War. I attach here many of the emails he wrote to me in 2011-2021: it emerges from them that he was already “smitten” with me before we met, from having been sent a DVD of an event in which I spoke in 2009. Nonetheless his amorous feeling for me reached its most intense in 2015-2018, years in which we never met; these emails show some degree of self-contradiction about the nature of the “love” he felt for me. Sometimes it was connected to my looks, sometimes it was “pure”. I believe that mainly he was attracted to my English accent and my writing about dance matters that were dear to his heart. He was particularly excited by the Sleeping Beauty questionnaire I conducted in 2015 with Alexei Ratmansky. The patterns of these emails suggest that his affections moved on in 2019 to others - perhaps he anyway was in love with more men than one at a time. I have heard that in his final years he was devotedly in love with a highly muscular dancer who bore no relation to me. Although I was sometimes perplexed by the emotion he expressed for me, I certainly felt honoured by it; and I think it important to note that he was most effusive with me when this connected with his passion for dance - when I shared research or critical discussion with him. Others knew him much better than I did; I share these missives (not a complete collection, but the most interesting, I believe) because they show touchingly how many strands of his mind were interconnected with his love of ballet. The quality of self-revelation within them is impressive and moving.

I remember him as a startling mixture of warmth, anger, intelligence, and enthusiasm. The scorn he expressed for de Valois was still scalding in his nineties, but his love (a word he used freely yet discriminatingly) for dancing, choreography, criticism, and dance scholarship was just as ardent. He loved to share the knowledge and memories he had gained; he loved adding to both that knowledge and his memories. Even after his hundred and second birthday, he was delighted to discover that he had found photographs he had taken in 1946 from the wings of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in The Sleeping Beauty, and to share them.

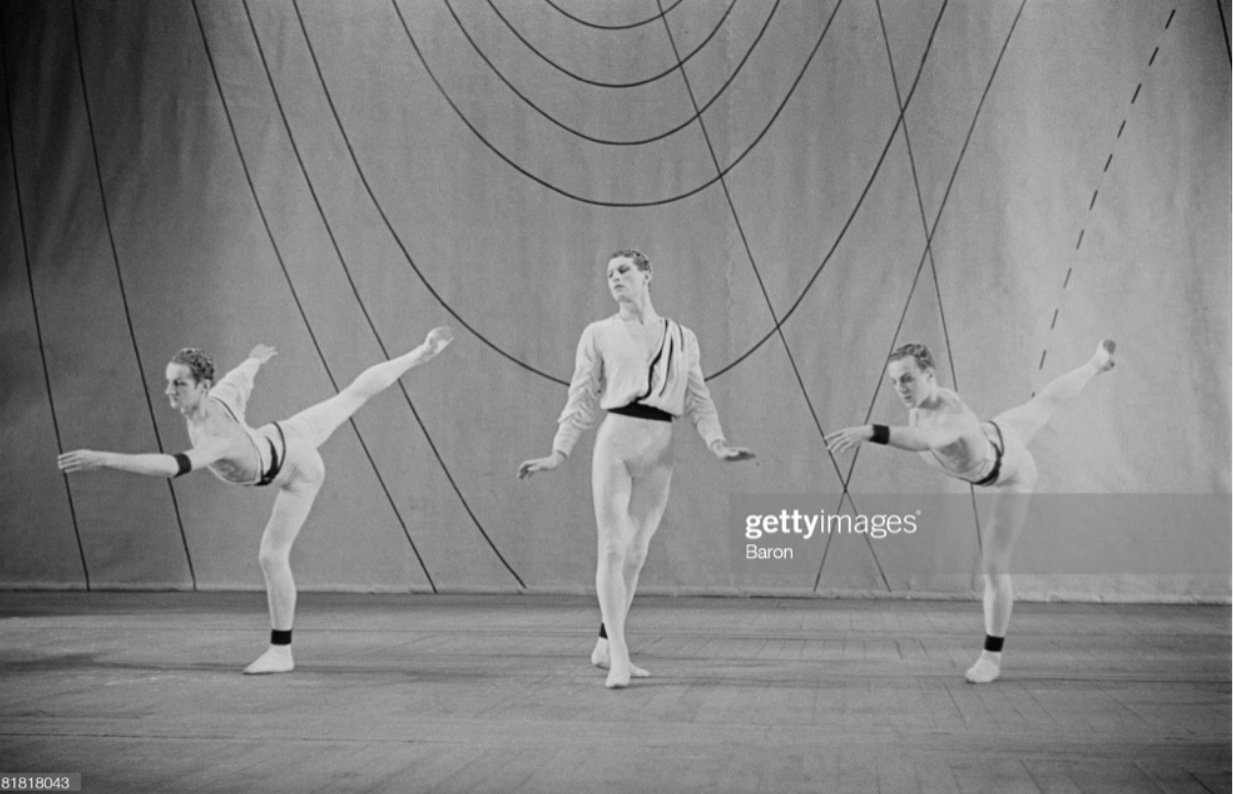

1. Henry Danton in Frederick Ashton’s “Symphonic Variations”, 1946.

2. Henry Danton (left), Michael Somes (centre), Brian Shaw (right) in Frederick Ashton’s “Symphonic Variations”, 1946.

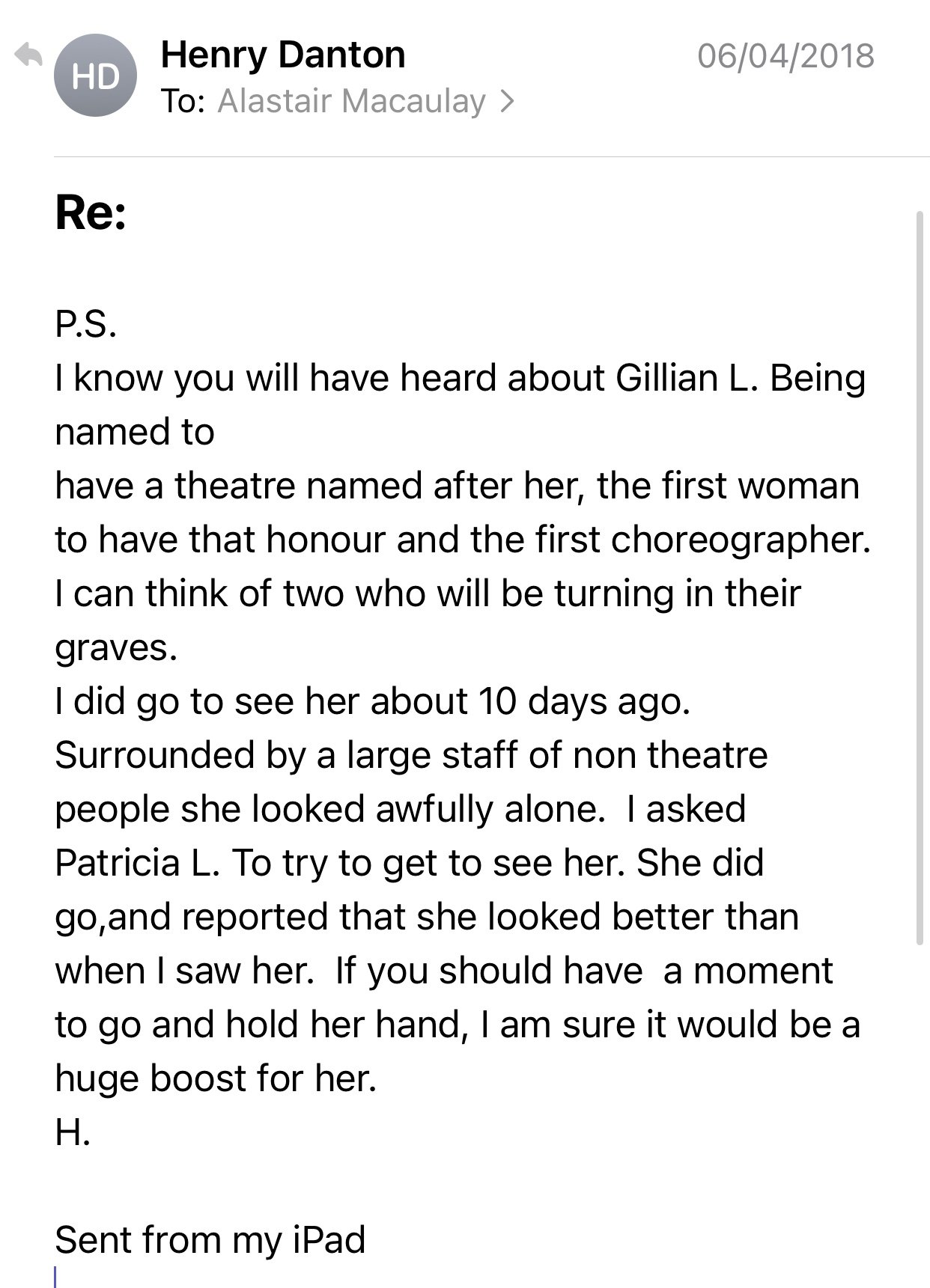

4: Henry Danton with four of his Covent Garden colleagues, seventy years later: Pauline Clayden (left), Jean Bedells, Danton (centre), Julia Farron, Gillian Lynne (right).

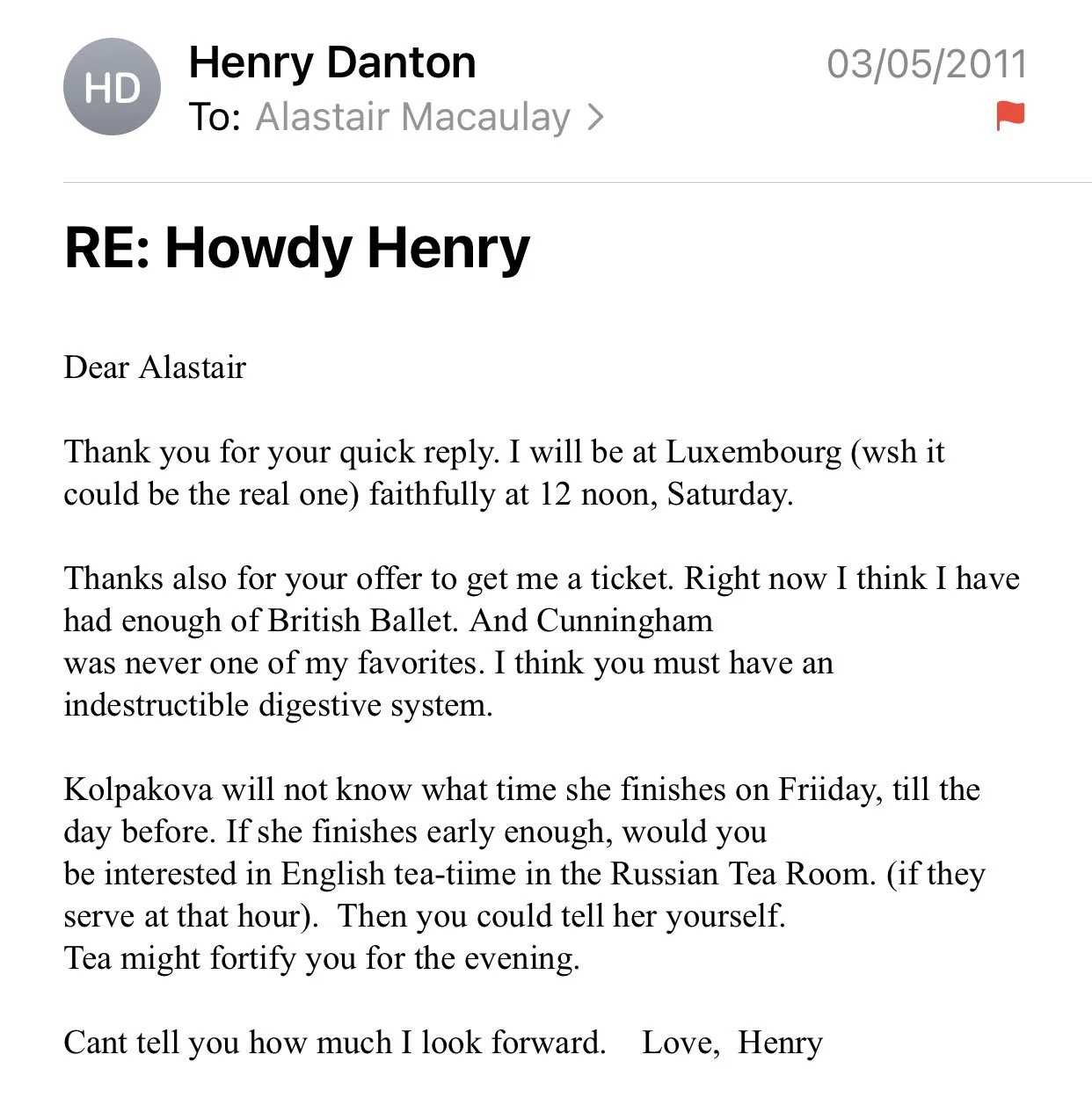

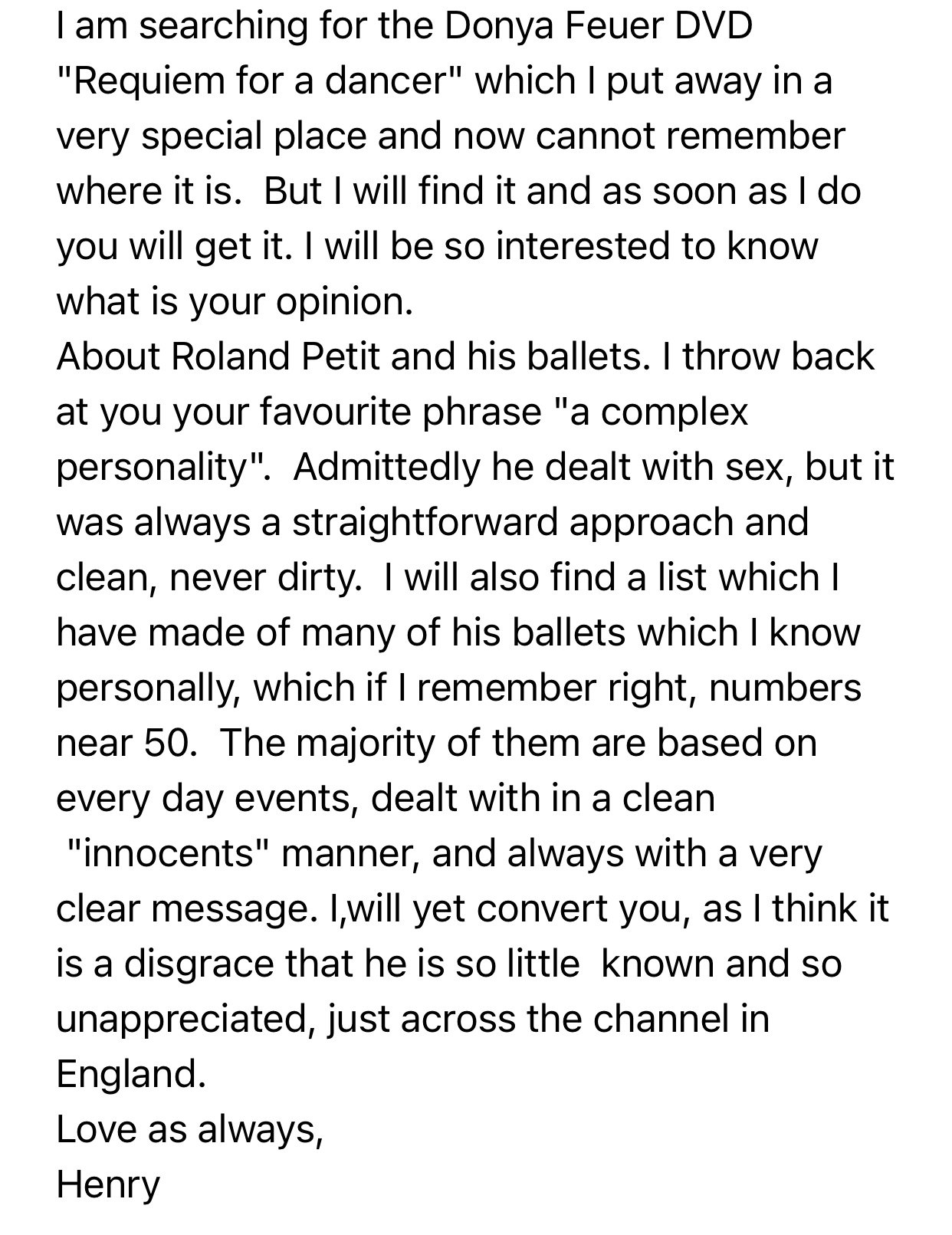

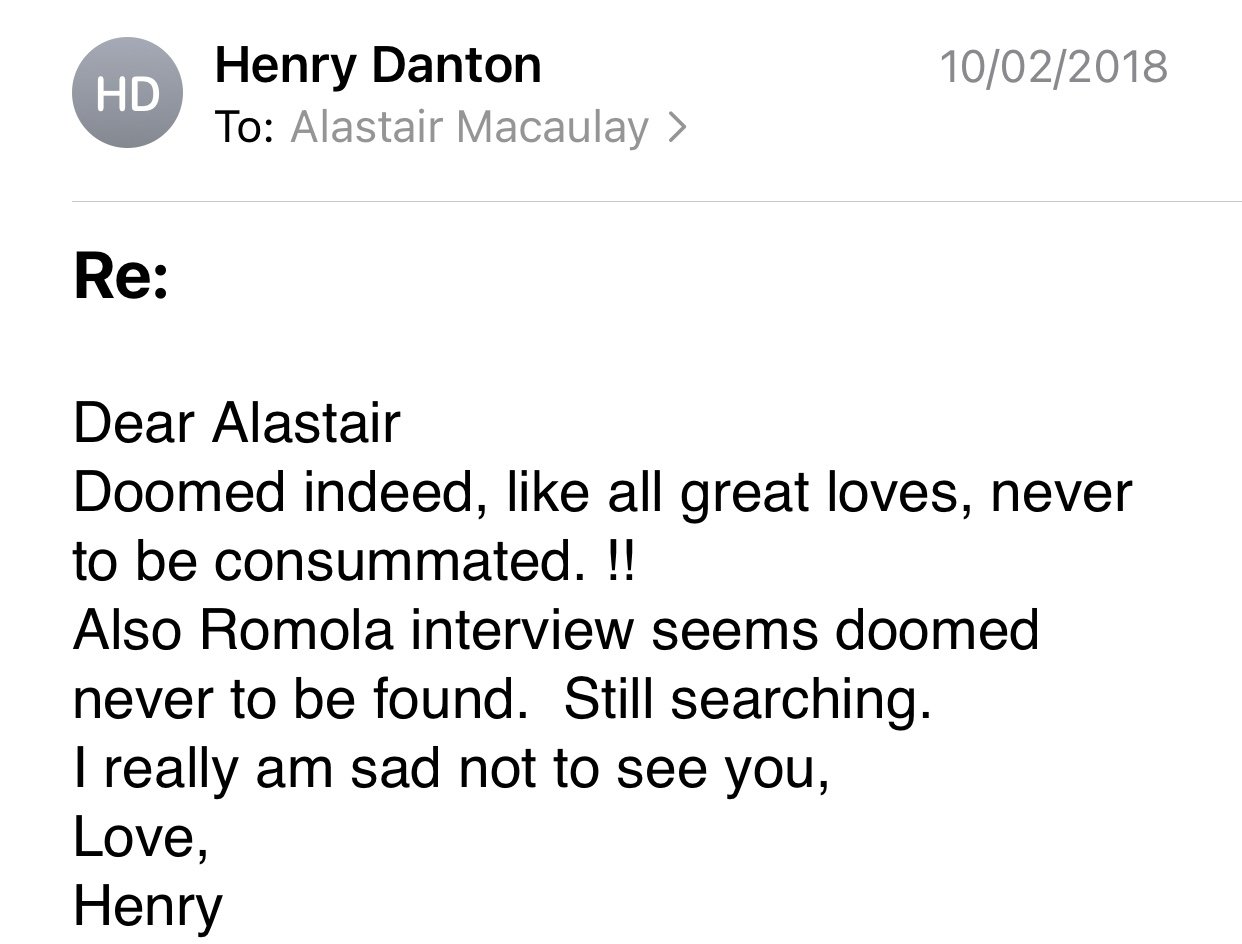

5. Danton’s first email to me: I had arranged to meet him at Café Luxembourg, New York. Having met once in London, this was to be our second meeting. In the event, it would also be our last meeting, although we hoped to meet again and corresponded until 2021.

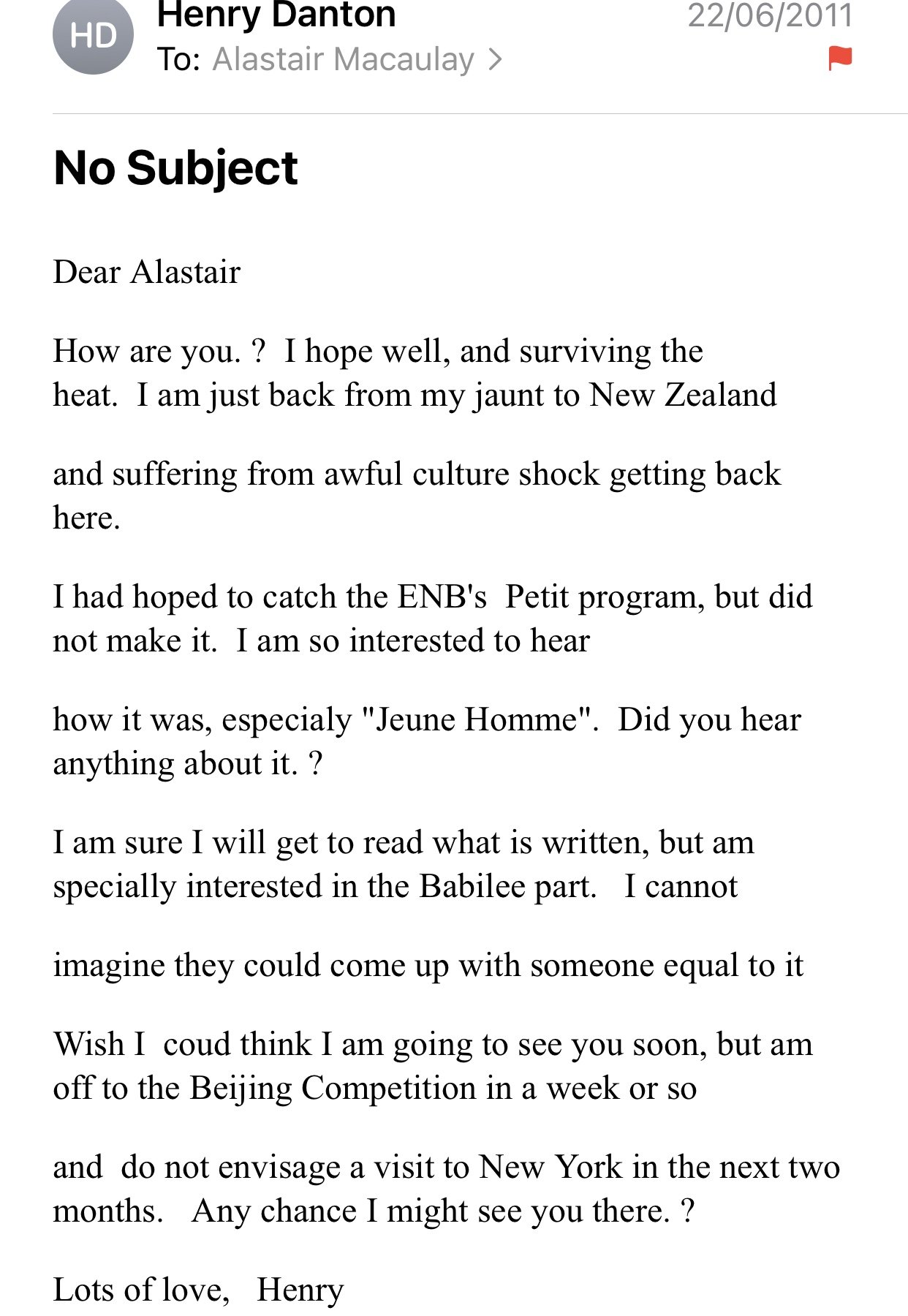

6.

7.

8.

9.

10. Here Danton refers to the 2014 documentary about the effect the Second World War had in making Britain love ballet, or at least in taking greater pride in British ballet. He refers to the seven minutes of silent colour film of “Symphonic Variations”, possibly at its second performance (some say at its dress rehearsal). He, like the documentary, neglects to say the film is played right-left instead of left-right.

Actually some eighteen minutes of film clips of perhaps six 1946 performances of “Symphonic Variations” (it had at least fifteen performances in its opening season) have surfaced, not on YouTube but at Huntley Films. They are played at different speeds and all from pronounced diagonals, and all projected the wrong way round, but they are an exceptional record that suggest the ballet was very different in style in that opening season.

In one of them, Gillian Lynne replaces Pamela May. She referred to this in one discussion, but Danton knew only of the film that showed the original cast; although he and Lynne had been friends, he spoke scornfully of her being erroneous about this identification.

11.

12. I do not know to what Danton refers here, but his remark demonstrates the residual and increasing Anglophilia of his final years.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17. Sergueeff, Sergueyev, Sergeev: there are many spellings of the one name. Danton worked with him during his six months (1943-1944) with Mona Inglesby’s International Ballet.

18. Danton was proud of having studied Stepanov notation and having conversed about it with Nicholas Sergueyev during his time with Mona Inglesby’s International Ballet.

19.

20.

21. In 21-25, Danton reacts to my “Sleeping Beauty” questionnaire with Alexei Ratmansky and others. This questionnaire may now be found on this website. Since Danton had known Nicholas Sergueyev, had studied Stepanov notation, and had danced in (and observed) the 1946 Covent Garden production of “The Sleeping Beauty” (and probably in the last performances of the 1939-1944 production, originally staged by Sergueyev), and since he had staged a “Swan Lake” in Australia on the strength of his understanding of Sergueyev’s production, Danton’s reaction is of particular interest.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27. Here Danton, hearing my second-hand report of Michael Somes’s poor partnering in his early career, gives a flash of malice about Somes, whom he did not admire or like. In a later email, he writes “Somes Ugh”.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33. I had reached my sixtieth birthday in 2015. Danton’s remark about thinking of me as “a most desirable 30 something” referred back to the first impression he had had of me in 2009, when Valerie Taylor Barnes had sent him a DVD of the Lincoln Center Bruno Walter Auditorium commemoration for her late husband, Clive Barnes: Danton had lunches with Clive and Valerie in the last year of Clive’s life. I was fifty-four at the time of the Bruno Walter event, but something about my looks, my English accent (that above all), and my manner seems to have gone to Danton’s heart before we ever met in 2011. In emails of the years 2015-2018, his expressions of affection for me turned into various protestations of love, complicated by his own conflicted sexuality. Although I was flattered, I was also perplexed, and did not reply with any seriousness. After his death, I discovered that he had often lost his heart to various men (a wide selection) over the decades. In 2019-2022, his affections had moved on to someone quite unlike myself.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40. On January 29, 2017, Danton wrote me three successive emails, here reproduced as 40-43 (42-43 include my own initial email to him and the email from a colleague that prompted it), 44-46 (in reply to a quick reply from me), and 47-48 (in reply to another reply from me).

41.

42.

43.

44. In his second and third emails of January 29, 2017, Danton replied to my views of Ninette de Valois and Frederick Ashton, neither of whom he liked. I am not sure his recollections of them in 1946 are quite accurate; he may have decided on his own version of the reasons he left the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1946.

He insisted on his reasons for disliking de Valois; I shared some of his reservations but pointed out reasons to remember her charm and her vision. He was not alone, however, in blaming de Valois for not engaging Vera Volkova on the Sadler’s Wells Ballet staff; Volkova remained the most admired teacher of the day, valued especially by Margot Fonteyn.

Danton claimed that he offended Ashton by rebuffing Ashton’s sexual advances, but in one 2011 conversation he also said he spent the evening at Ashton’s flat when, at a late hour, Michael Somes arrived, as if making sure that Danton moved on. Somes, though generally heterosexual, knew his status as the great love of Ashton’s life from the late 1930s up to at least the mid-1940s. Ashton, however, seems to have been capable of entertaining more sexual affections than one simultaneously. Possibly Danton did too, but, throughout his life, was capable of denying any capacity for “that kind of love”. If he rebuffed Ashton by claiming that his inclinations were more heterosexual than they were, and if Ashton felt Danton’s affair with Volkova was sexually insincere, Ashton could well have been barbed to Danton.

45.

46.

47.

48.

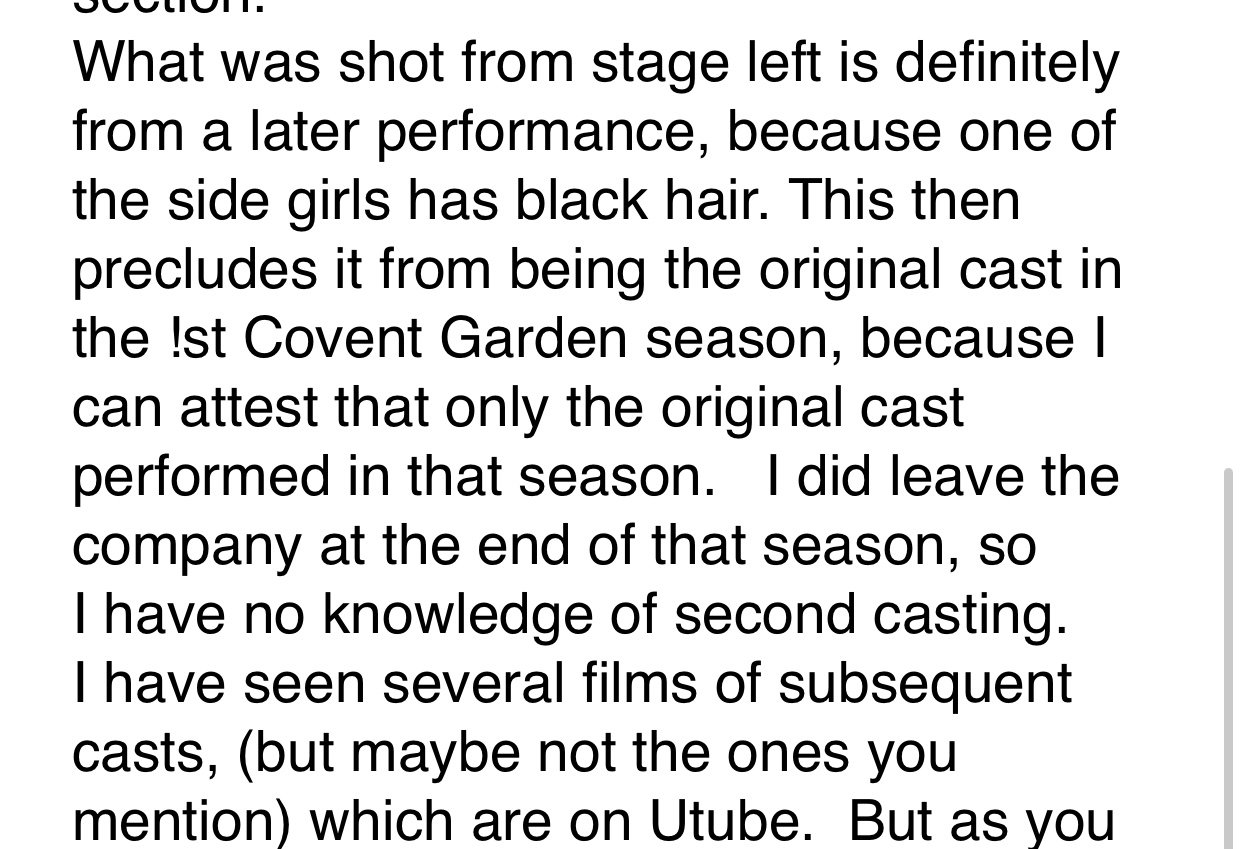

49. Nos 49-51 are two successive replies to one in which I had sent him a YouTube video of a 1977 Royal Ballet performance of “Symphonic Variations” (led by Merle Park and David Wall) at Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee gala.

50. Nos 49-51 are two successive replies to one in which I had sent him a YouTube video of a 1977 Royal Ballet performance of “Symphonic Variations” (led by Merle Park and David Wall) at Elizabeth II’s Silver Jubilee gala.

51.

52.

53.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

64.

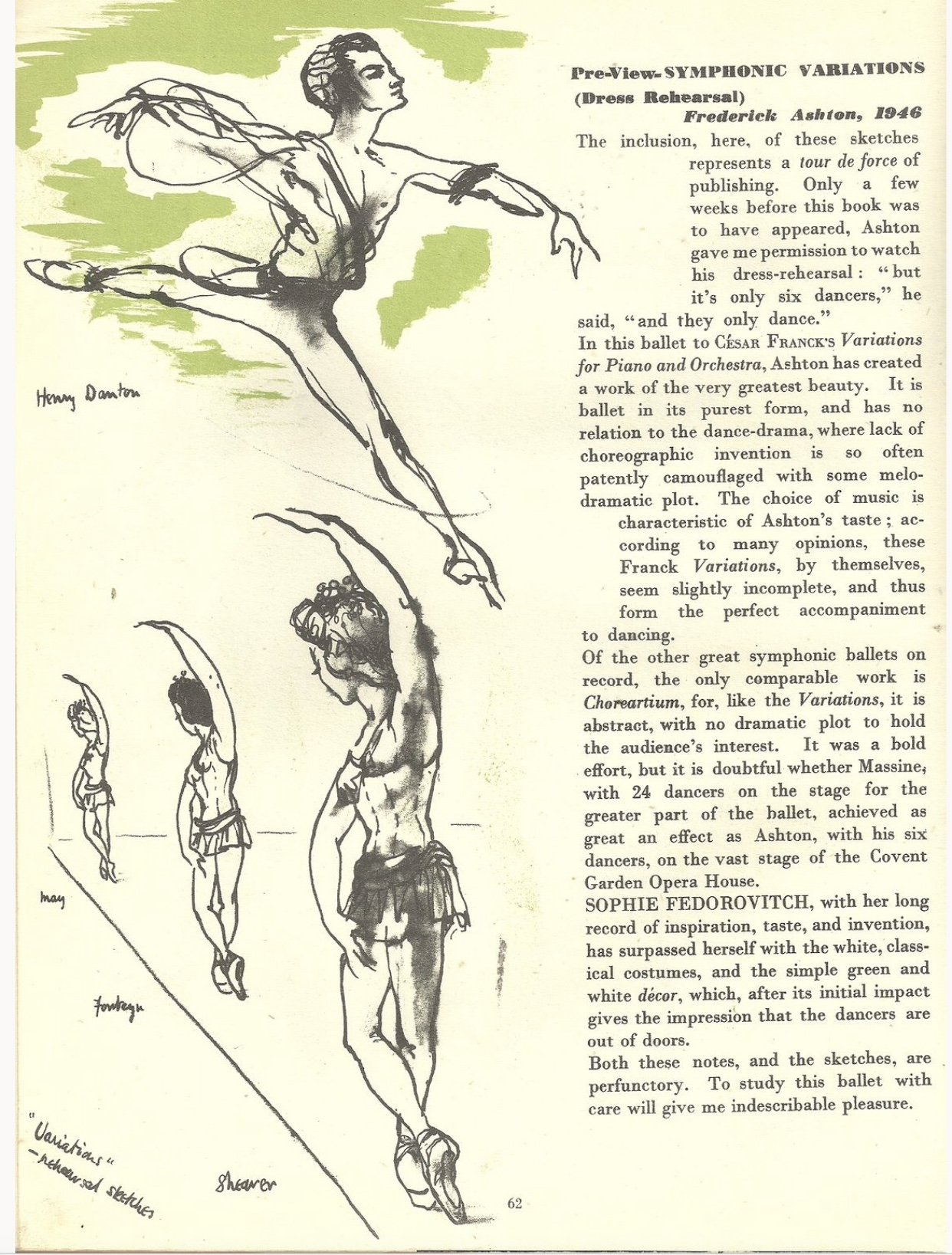

65. Here Danton attaches Kay Ambrose’s sketches from the Covent Garden April 1946 dress rehearsal of Frederick Ashton’s “Symphonic Variations”. At the top, he is showing in the grand jeté . Below, Ambrose shows (as seen from the side) Pamela May, Margot Fonteyn, and Moira Shearer in the women’s opening dance of “Symphonic Variations”. Danton had never danced an important solo role at Covent Garden, but these three women were the three ballerinas dancing Aurora in the company’s new production of “The Sleeping Beauty” there.

66.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92. I had been friends with Joy Williams Brown since 1999. In 2018, I discovered that Danton had partnered her in the 1949-1950 American season of Roland Petit’s Ballet de Paris.

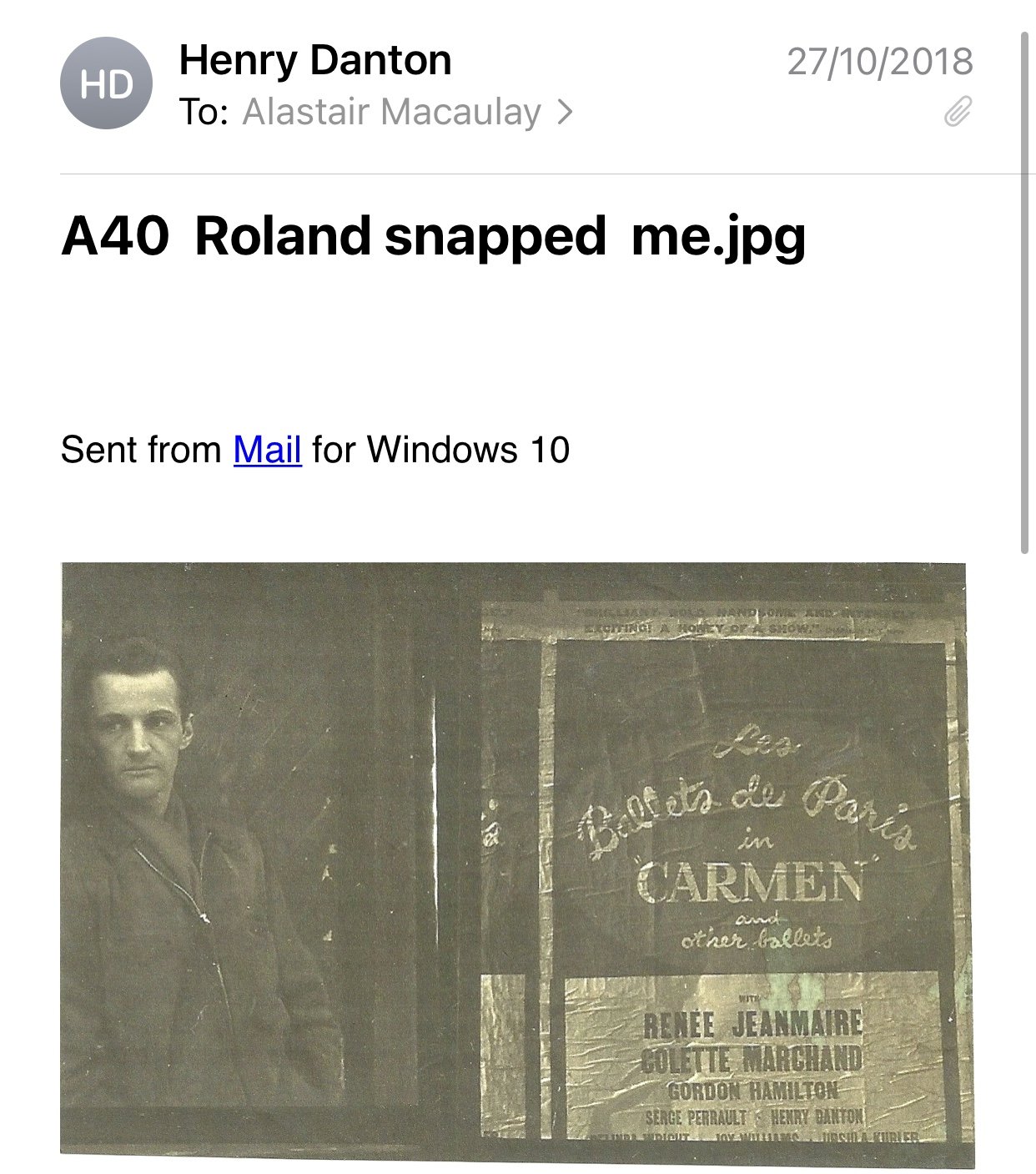

93. Danton had expressed admiration for, and fascination with, Alexei Ratmansky for some years.

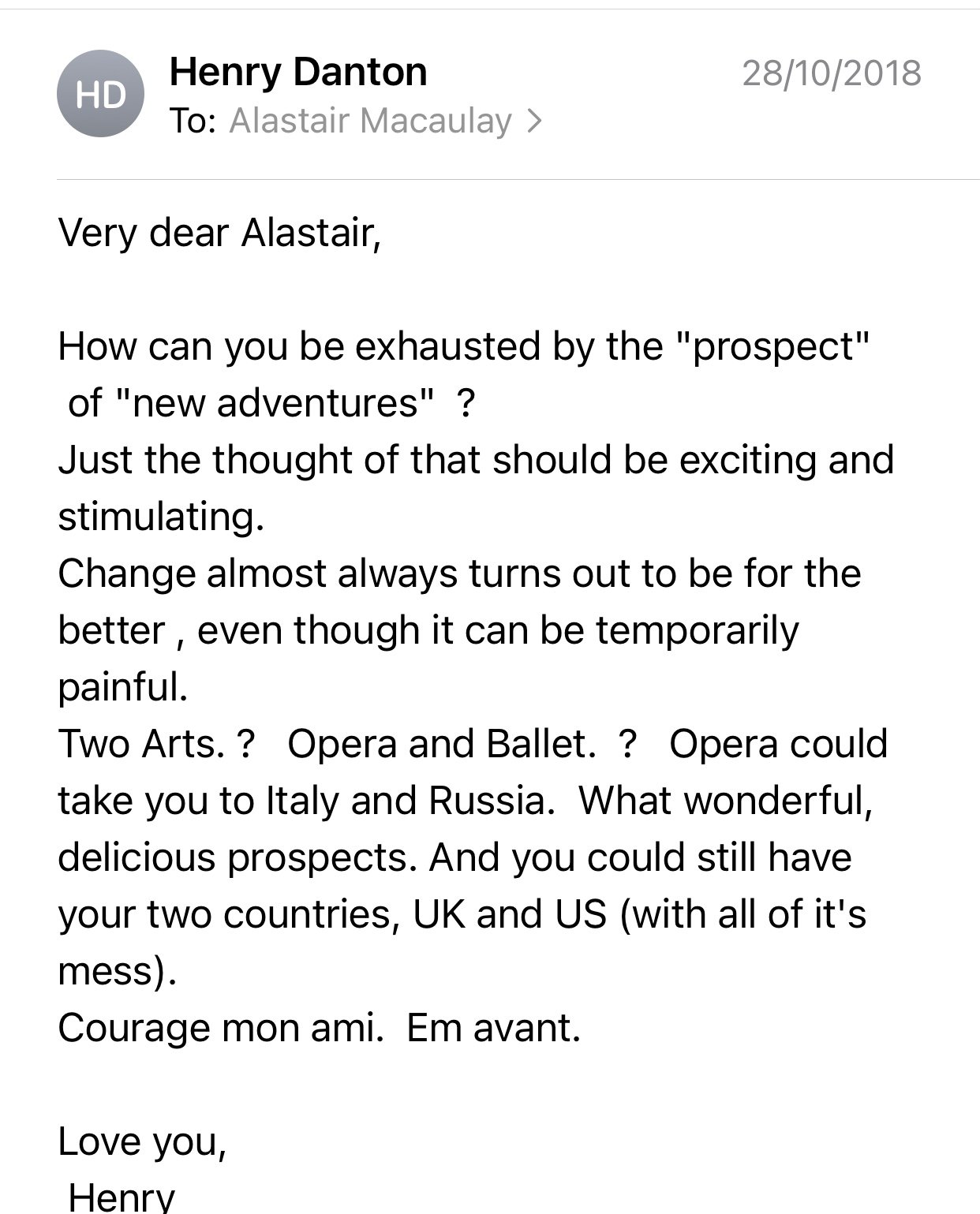

94. Danton had just heard the news that I was stepping down from my post as chief dance critic of the “New York Times” at the end of 2018.

95.

96. Joy Williams and Henry Danton in Roland Petit’s “Le Rendezvous”.

97.

98.

99.

100. Another photograph of Henry Danton and Joy Williams in Petit’s “Le Rendezvous”.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

108.

109.

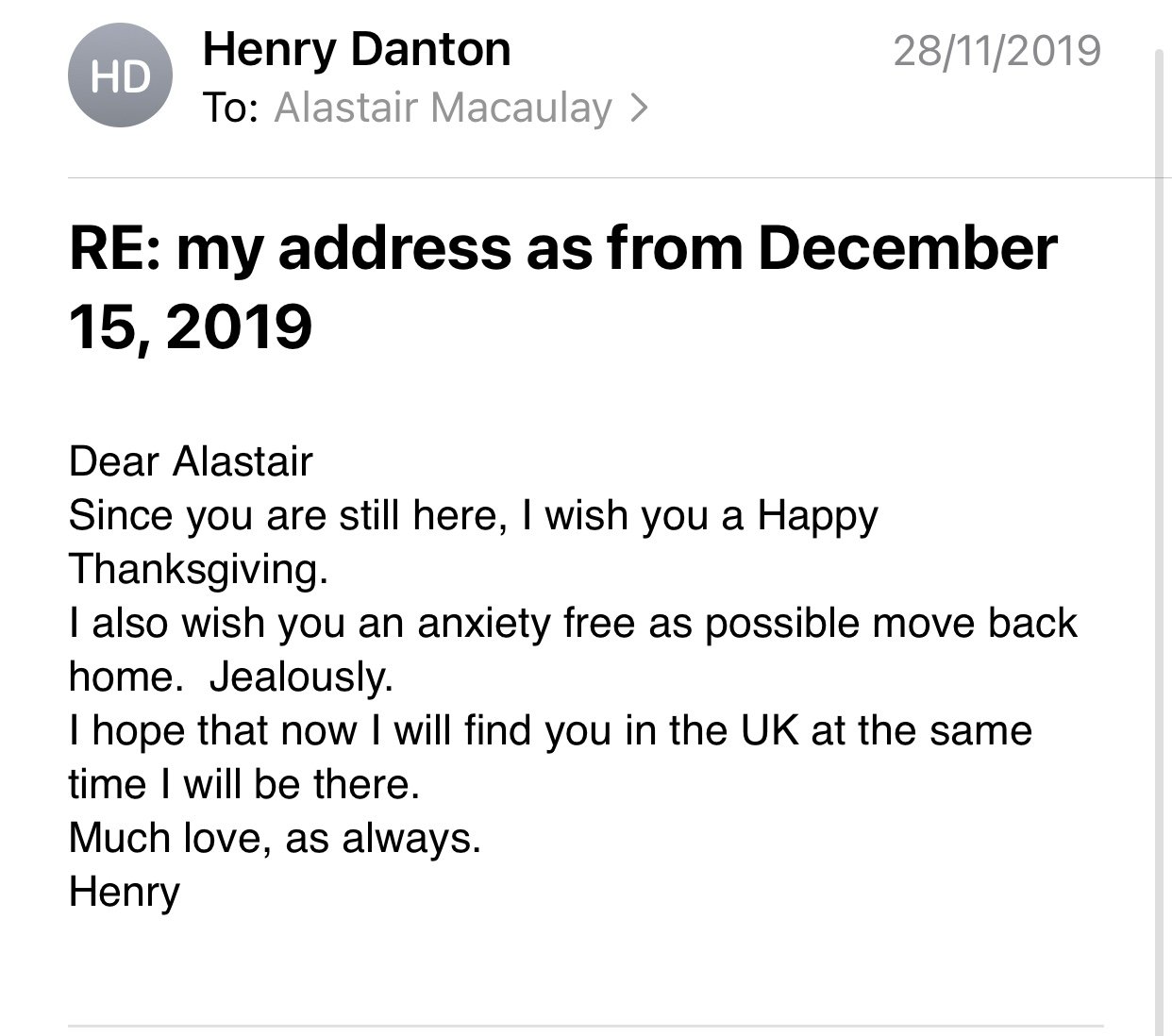

110. Danton’s use of the word “here” refers to my being in the United States, as I was in January-May and September-December of 2019.

111.

112.

113.

114.

115.

116.

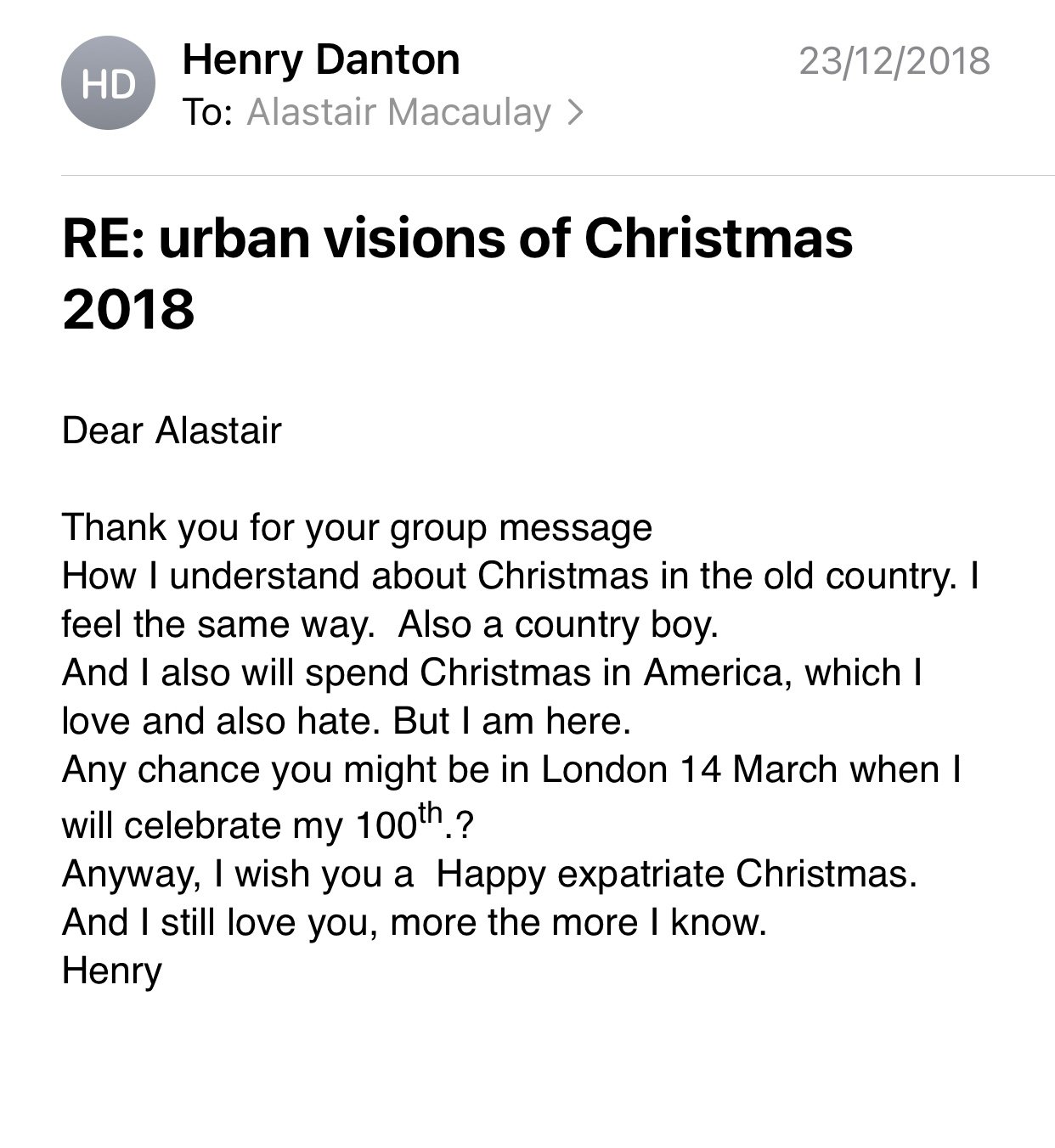

117. This was a group email, not sent to me alone.

118.

119.

120.

121.

122.

123.

124.

126.

127. This missive was unsigned. Possibly Danton was sending it to several correspondents.

128. In my missive to Danton, I had mentioned the two world wars and the world economy, but I believe he misunderstood the point I was making.

129. Nos 130-139 are the piece about him, by Anne Marie Wrange, that he attached in English translation.

130.

131.

132.

133.

134.

135.

136.

137.

138.

139.

140.

141.

142.

143.

144.

145.

146.

147.

148.

149.

150. This photograph by Henry Danton, taken from the wings at Covent Garden, shows Margot Fonteyn as the Vision of Aurora in Act Two of The Sleeping Beauty.

151. This Danton photograph shows Beryl Grey as the Lilac Fairy in her variation in the Prologue of The Sleeping Beauty.

152. This photograph from the wings shows Margot Fonteyn as Aurora in the Wedding pas de deux of Act Three of The Sleeping Beauty with David Paltenghi as the Prince. This is the only photograph of the Fonteyn-Paltenghi partnership I know: he was more usually partner to Beryl Grey or other Auroras. A tall man, he had limited dance technique, but looked striking in the Prince’s Act Two pink/red hunting coat. Fans in the Covent Garden amphitheatre gave a sofa there his name because it was that colour: “Meet you on David Paltenghi in the interval”. He later became a choreographer for Ballet Rambert.

153. I sent Danton this photograph by Roger Wood of the very final moment of Ashton’s Symphonic Variations. Michael Somes (right) has his arm raised. I assumed that the man in the centre of this photograph was Danton. His replies come in 154.

154. Danton here refers to Brian Shaw.

155. According to Danton, this super-radiant photograph by him from the wings of Margot Fonteyn shows her as the Vision of Aurora in Act Two of The Sleeping Beauty. It should be remembered that in 1946, the year of this photograph, Aurora’s Vision Scene variation was the one choreographed by Marius Petipa (to the Gold Fairy music) rather than the variation choreographed in 1952 by Frederick Ashton (to Tchaikovsky’s own music for the Vision variation).

I responded that this glorious photograph showed Aurora surely in the Act Three variation, but Danton replied in three emails: 156-158.

156.

157.

158. An excellent point.

159. Danton sent this unsigned Christmas greeting to a number of his friends. For me and several others, it was the last missive we received from him.