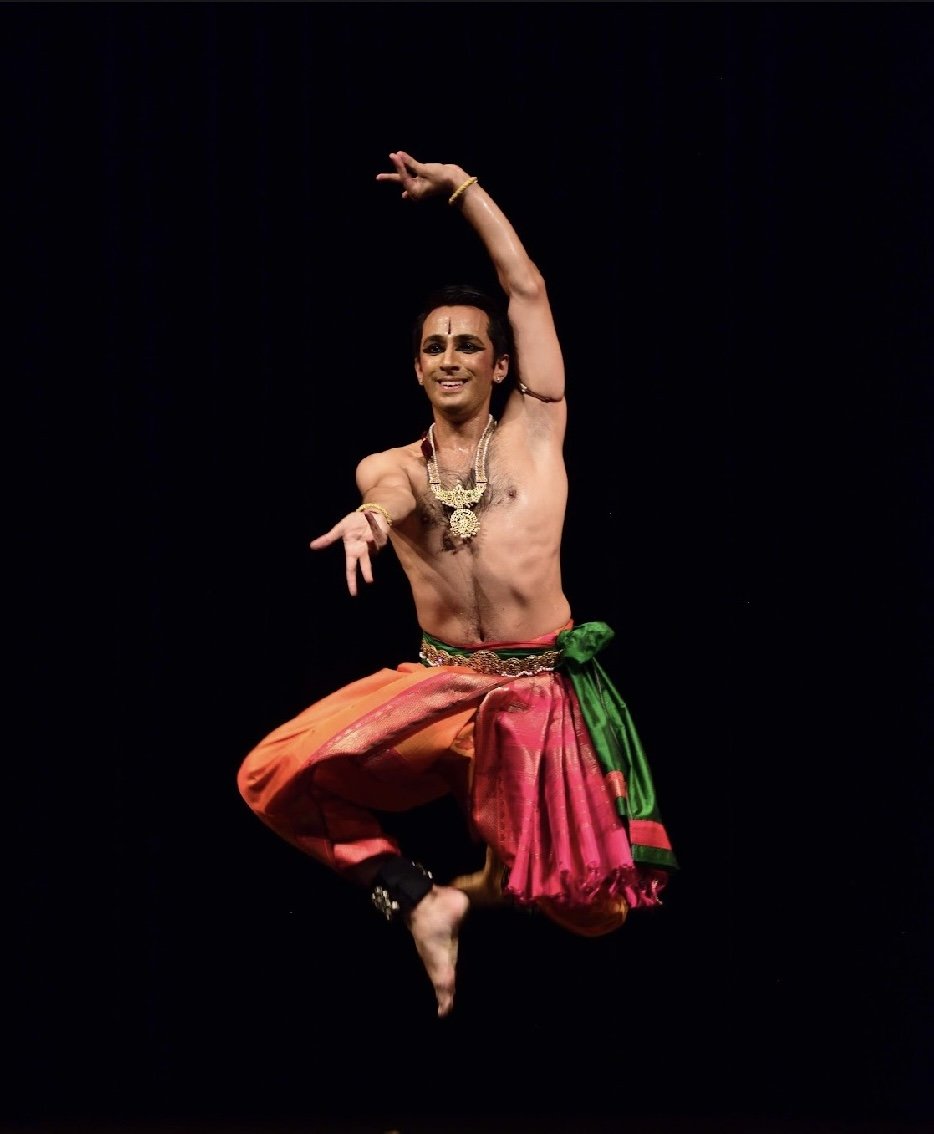

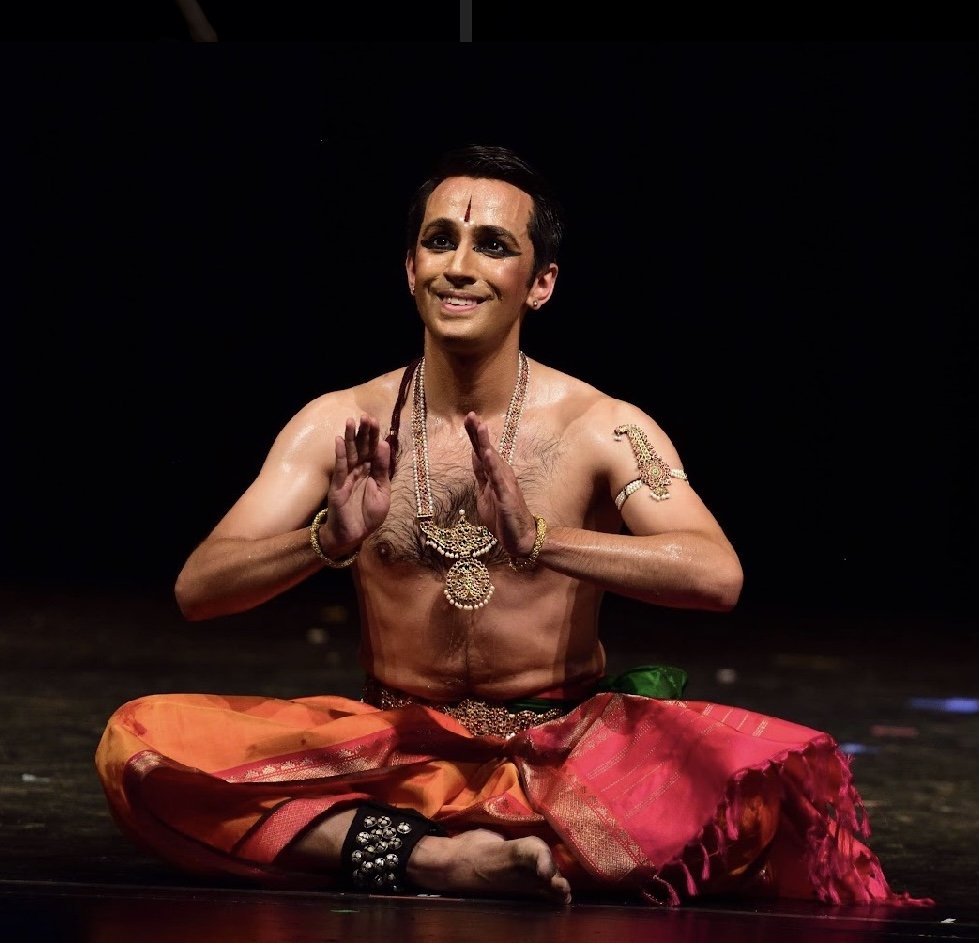

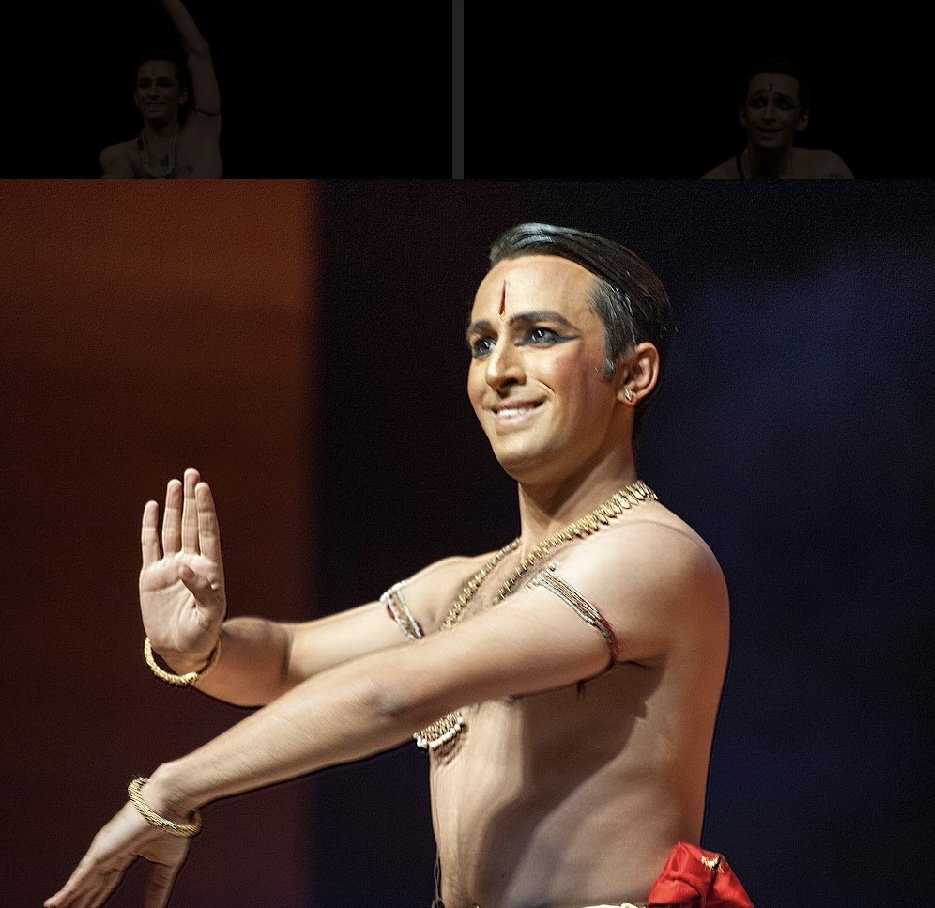

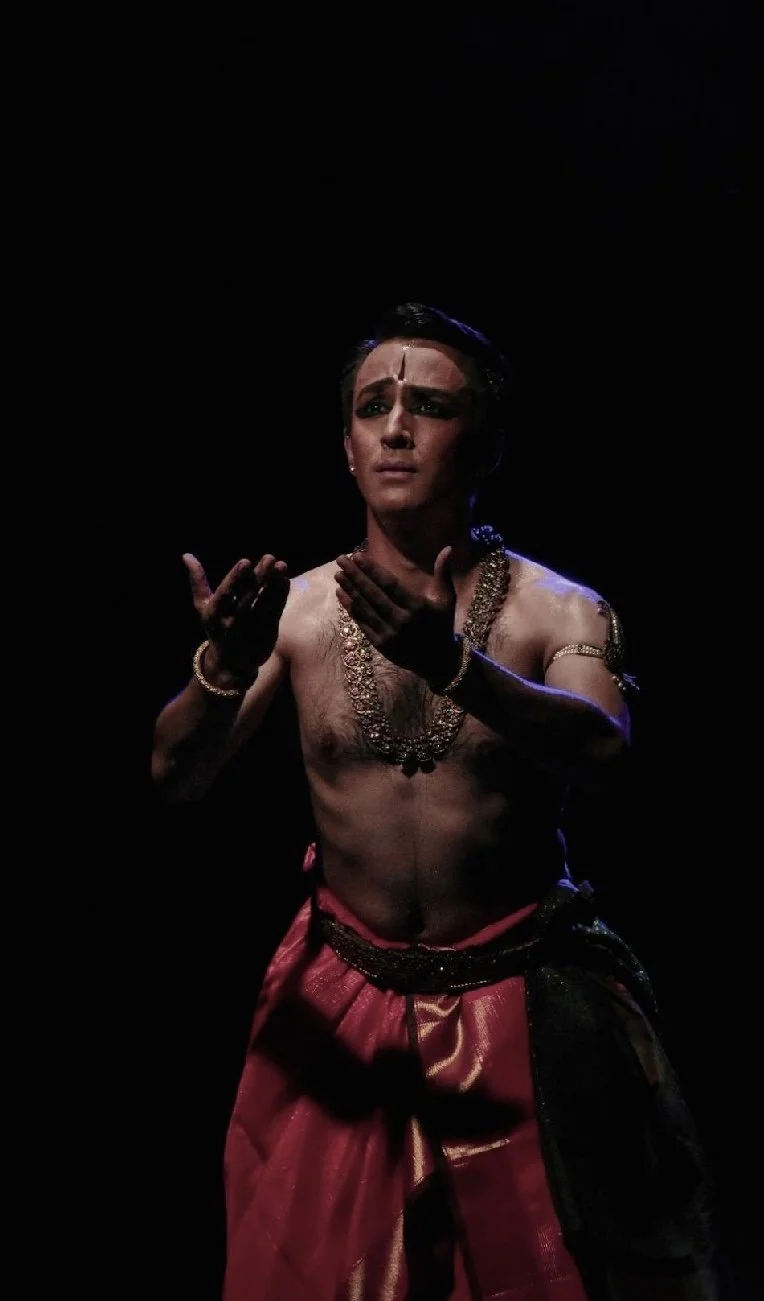

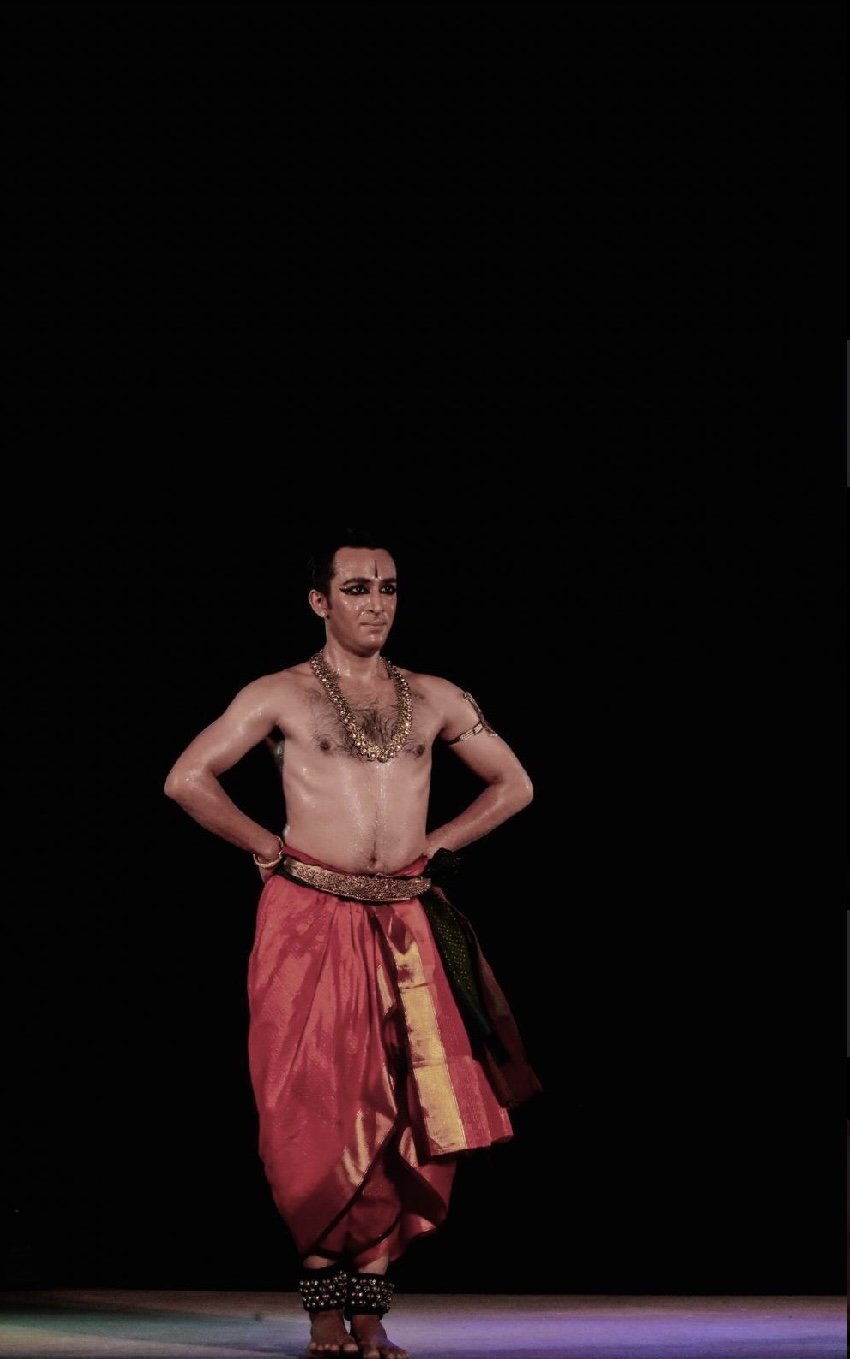

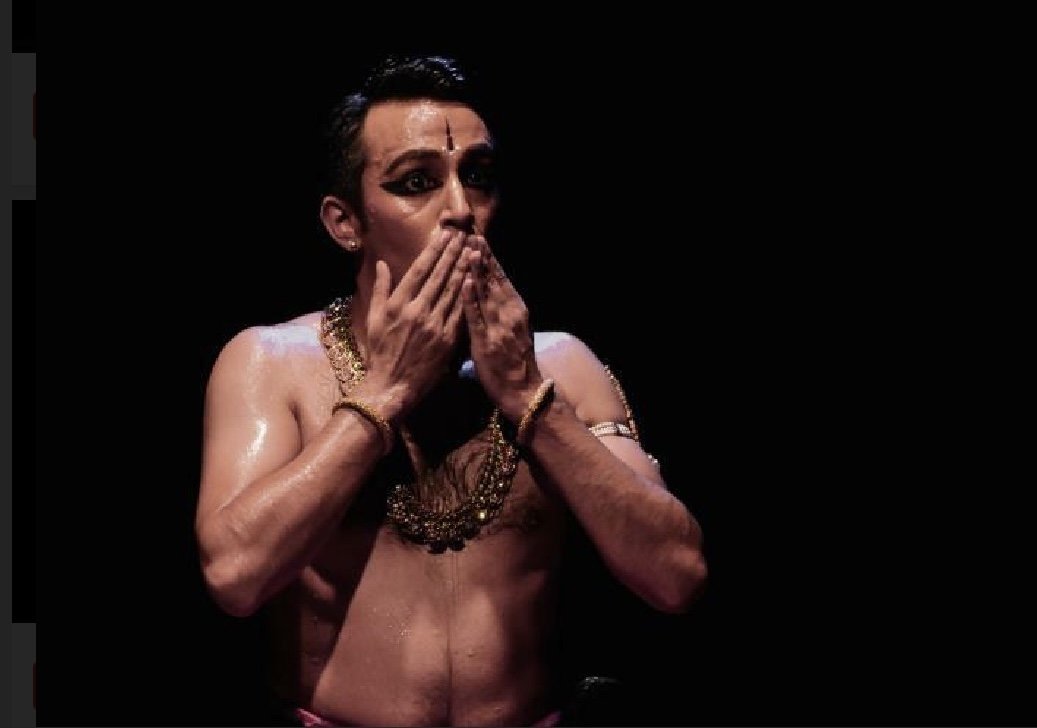

Christopher Gurusamy and “Krishna - Knave of Hearts”

To watch the Bharatanatyam dancing of Christopher Gurusamy is to see an age-old genre recharged, brilliantly revitalized from within. He doesn’t bring any neologisms to change the rich tradition of this tradition with any neologisms, and yet he brings it a power, a sweep, and an attack that make it feel not old but startlingly young. With a deep chest and theatrically communicative features, he has virile glamour.

Gurusamy, who is both Indian and Australian, is now in his early thirties. Bharatanatyam is a genre he began to study in childhood; his studies led him to the great academy of Kalakshetra in Chennai (Madras). Chennai is the capital city of the southwestern state of Tamil Nadu, the state in which Bharatanatyam had its origins, centuries ago; many of the temples where its great devadasis (bayadères) refined their art are still active. Since his graduation, Gurusamy has remained based in Chennai, ever since, working hard and with self-mockery (he often sends himself up in his Instagram posts), absorbing different facets of his dance tradition. He’s danced in Britain before; I’ve only seen him live before in his New York debut in 2017. Especially within India, he’s spoken of by senior practitioners of his genre as exceptional, rightly so.

On Saturday 2 April, he performed as part of a two-part Bharatanatyam evening conceived, organized, and choreographed by Stella Uppal Subbiah. The whole soirée – taking place at The Bhavan in West Kensington, a few yards from a flat where Mahatma Gandhi lived when he was studying law in the late nineteenth century - was titled “Krishna, Knave of Hearts.” Its individual dances reflected a few of the myths whereby the mischief and the lovable beauty of the great god Krishna are remembered. Gurusamy is well cast as the multifaceted Krishna: his personality has naughtiness and charm, his looks have beauty and force, and his dancing often seems superhuman. His Varnam solo, thirty-six minutes long, was the great event of the event’s first half and indeed of the whole event; but he also danced in the second part, and joined others, making group dances all the more vivid by the intensity with which he joined them.

Like most of the classical genres of Indian dance, Bharatanatyam alternates between abhinaya (expressive mime) and nritta (pure dance). Gurusamy has great physical gifts for abhinaya - his eyes, mouth, hands, and arms all project communicatively – but seems to have started with the wrong personality: where abhinaya’s greatest exponents, working as if from inner repose, draw you into their imaginative world, his instinct seems to be always to reach out, to grab your attention, to entertain. He isn’t always spellbinding; he’s working too hard for that. Yet he’s never less than compelling. At no point is his performance an exercise for his ego: he’s addressing larger elements.

When it comes to nritta, who can compare with this force-of-nature powerhouse? The very slap of his bare feet on the floor sounds like the crack of a whip. In basic steps, he seems to consume more space than other dancers. And he exemplified how Bharatanatyam dancing can seem more urgently three-dimensional than any other form, as the dancer gestures right! left! back! forward! up! down! in rapid succession, the body twisting powerfully with each full-armed gesture. He’s particularly breathtaking in the ardent plunge taken by his torso from upstretched positions to floor-skimming ones, but I’m also happily amazed by the eager stretch with which he hurls an arm out to either side, leaning from the waist as he does so, and boldly flourishing the individualised fingers of his hands like an open fan.

The other dancers – all female, some of them shown on film – weren’t of his order, but Stella Uppal Subbiah performs with impressive accomplishment, while her colleagues show different levels of skill in entirely happy and pleasing ways. Gurusamy never upstaged anyone in ensembles: he suggested a Krishna whose erotic charm for the women around him was happily inspiring. Although the music by Tiger Varadhachariar (1876–1950) was recorded – after one introductory flute solo played onstage – its sonorities and pulses felt far from distant, as if the musicians were in the wings.

<Originally published in “Dancing Times”, May 2022>

@Alastair Macaulay, 2022

1: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

2: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

3: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

4: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

5: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

6: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

7: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

8: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

9: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

10: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

11: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

12: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

13: Christopher Gurusamy. Raju Photography, 2019.

14: 20, Baron’s Court Road, London W14. Photograph: Alastair Macaulay

15: Blue plaque at 20, Baron’s Court Road, London W14. Photograph: Alastair Macaulay.

.