The London 2021-2022 opera season: four new productions

At certain points in the last fifty years, the most remarkable theatre productions in London have occurred in opera. The 2021-2022 season is proving one of those times.

The Valkyrie (ENO); Theodora (RO); The Cunning Little Vixen (ENO); Peter Grimes (RO)

* * * * * *

The Valkyrie, English National Opera, 19 November, 2021

Richard Jones’s new production of Wagner’s “The Valkyrie” deliberately strips this music drama of grandiosity or nobility, while maximizing elements of cartoon comedy. Sieglinde(Emma Bell) wears jeans. Her husband Hunding undoes his trousers to rape her (apparently a regular occurrence) before her knockout drug lays him flat. Brünnhilde (Rachel Nicholls) wears patterned culotte pyjamas. Her father Wotan (Matthew Rose) wears a red anorak; Brünnhilde’s eight Valkyrie sisters wear green anoraks ones. And the Valhalla in which Wotan lives with Brünnhilde and his wife Fricka is a chalet. Wotan has some human-sized Disney-like ravens who move the scenery now and then. The Valkyries have two-legged human-size horses. And there’s a storm imp who dances gleefully on the spot during the storm music.

This production received its premiere with English National Opera on Friday 19 evening; five further performances follow until December 10. Much of what happens onstage is traditional enough in observing Wagner’s stage directions. A tree growing in the middle of Hunding’s kitchen, with a sword in it. Brünnhilde puts a breastplate on over her jimjams; she, Hunding, and Wotan carry spears.

More unusually for a modern production – refreshingly - Jones sometimes has his singers simply stand still as they look at each other across the stage space just as Wagner asked. The orchestral music tells us everything about what’s going on inside them. We start to feel the instinctive physical longing as Siegmund (Nicky Spence) and Sieglinde gaze at each other.

When Brünnhilde rushes across the stage to embrace her father Wotan after their long argument, the emotion is intense. Indeed, the fact that the king of the gods is wearing an anorak makes the emotion all the more immediate. During Wotan’s long monologue, his dark counterpart, Alberich, becomes visible here, a huge malign figure but visually enough like Wotan to acquire nightmare force.

The first night had problems. Spence sang – extremely well – despite a heavy cold; Susan Bickley acted the role of Fricka but, thanks also to a cold, silently, while Claire Barnett Jones sang the role from a box beside the stage. Jones had planned some flame effects for the conclusion of Act Three, but these were cancelled, due to Westminster City Council’s safety precautions. (It’s to be hoped that later performances provide at least some element of changed light in response to Wagner’s music here.)

The production is carried by its men. Martyn Brabbins conducted with a strong, expansive lyrical current throughout. There are moments when the music would profit from a faster pressure; but this is eloquent playing from a committed orchestra.

Rose sings Wotan like no singer I’ve heard before – my “Valkyrie” experience goes back to the 1970s - with a glowingly bel canto command of glowing vocal tone and keenly communicative diction. In the great long monologue of Act Two, his thought is alive in rhythm (a marvellously propulsive grasp of Wagner’s anapaests), in words, and in changing vocal colour. Nothing is forced; his godly authority is achieved by intelligence, not by overblown weight. And never, even on records, have I heard anyone sing the final two phrases (“Who fears the point of my spear, He’ll never pass through the flames”) with such wonderfully taut, bright, architecture. The topmost note - “spear” (“Speer”) - effortlessly attacked and gleamingly sustained, was the evening’s single most glorious vocal sound.

It’s to be hoped Rose will improve in two ways. He has a bad habit of anticipating the beat. (He stopped doing this when he was in the role’s final paragraphs.) And he often enters important notes by leaning into them without vibrato, before allowing his vocal tone to relax; but, since his vibrato is a light unobtrusive quiver and since he never uses it as a way toscoop up into the eventual note, this mannerism may not prove dangerous. Already he is one of the important and most singular Wotans of our day.

Spence - another with good diction and handsomely firm vocal lines - establishes the tragic character of the outsider Siegmund by his dark chest tones (Gunther Treptow, one of the role’s finest interpreters on record, came to mind) and by his uncouth, loose-haired, unkempt-beard appearance. I’d say he’s an embodiment of virile pathos, but he’s uneven physically. Though he has a good stage face, its expressions stay TV-scaled, and, though he stands well, his way of running is the opposite of heroic. Vocally, he’s most moving, catching both the character’s psychological desolation and the love that transforms his existence.

While I enjoyed both Susan Bickley’s silent acting and Claire Barnett Jones’s singing, this split-focus effect perforce diminished drama. Emma Bell’s loose vibrato and execrable diction do no favours to Sieglinde. On the few occasions her words are audible, she sounds as if English were her fourth language. More often, the distance between her words and those written on the surtitles is a cause for embarrassed amazement (how did this come to sound like that?). Brindley Sherratt brings dangerous, imposing, vocal heft to Hunding. (reminiscent of Clifford Grant, who sang this role in this company’s classic bygone performances).

Rachel Nicholls, playing the title role with youthful enthusiasm, only gradually settles into vocal form: she’s initially squally. But none of this opera’s great emotions becomes more powerful than the conflicted love between this daughter and her father. Jones makes their affection begins playfully: Brünnhilde rides on her father’s back like a little girl playing gee-gee. When she observes the love between Siegmund and Sieglinde, she nestles up to them as if she wants a part of it. Finally, as she finds words to explain her great act of defiance against the father she so adores, she comes of age.

The new singing translation, by John Deathridge, has many wonderfully eloquent passages (“As I reigned, I still needed rapture”; “Shy, astounded, I stood in shame”) and some awkward patches of translationese. Much is missing from this production - but the thrilling grip of Wagner’s thought about many layers of existence is never in question.

<Slipped Disc>

* * * *. * *

Theodora, Royal Opera, 1 February, 2022

Three parallel rooms are visible across the Covent Garden stage. On the right, Joyce DiDonato, as a leading Christian dissident Irene, is leading the embassy staff in thoughts of liberty and Christian prayer. In the centre, sex workers are pole-dancing. On the left, Julia Bullock, as Theodora, another embassy worker, is lying motionless, numb, in post-rape trauma on a bed.

This is just one haunting image from the Royal Opera’s production of Handel’s Theodora, new at Covent Garden on Monday 31 January. Fabulously suspenseful over three hours and a half as conducted by Harry Bicket and directed by Katie Mitchell, this is an astonishing, multi-layered triumph.

It’s a superlative event in theatre of any kind. Mitchell has been often a controversial director in theatre and opera, sometimes irksome. But this Theodora, the greatest achievement I’ve seen from her in over thirty years, find her at her most imaginatively poetic: she conjures marvels with the basic ingredients of time, space, and meaning. Often, as in the scene I’ve described, we’re shown very unalike actions occurring simultaneously, in two or three adjacent rooms.

Words say one thing, music suggests another, stage actions show yet further complexities. And in several key scenes, crucial events unfold in stunningly slow motion, even while the music’s pulse keeps beating steadily. It’s as if we’re watching out of time, in shock. Mitchell’s staging transposes Handel’s narrative about Roman overlords and Christian martyrs from fourth-century Antioch to a twentyfirst - century embassy. Subversive turmoil is brewing from the kitchen staff(Christian rebels). The public and the personal are combined in a riveting mix of politics, religion, class, sex, love, humiliation, and trauma. Sets are by Chloe Lamford, costumes by Sussie Julin-Wallén.

The way that drag and pole-dancing fit into this tale without sensationalism is all part of Mitchell’s special alchemy. Even in the closing seconds, you watch on tenterhooks: what will happen next?

Musically enthralling at every point, this Theodora is led by the American soprano Julia Bullock as the heroine Theodora, the Polish countertenor Jakub Joséf Orliński as her lover Didymus, and the American mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato as Irene, a central figure among the staff’s Christian dissidents. At every moment, singing and playing are dramatically impelled, perhaps especially in vocalembellishments. Even passages of energetic passagework tug us into the narrative, rather than hurl out display.

Bullock and Orliński lead the production into its most unforgettably poignant scenes. Theodora is punished by being made a sex worker, with glittery short dress, platinum blonde wig, and high heels; Didymus, discovering in full her degradation, saves her only by swapping clothes. Their scenes here become heart-in-mouth experiences . The way that Bullock/Theodora’s thoughts turn to God as she finds herself between two pole-dancing prostitutes perfectly illustrates the escapist flights of a traumatised victim’s mind. When Orliński/Didymus - gorgeous in Theodora’s tart apparel – takes up pole-dancing, he makes it a bleakly despondent embodiment of hopelessness.

Bullock (though her diction could be clearer) fills her music with feeling both dark and bright. Orliński, a Handelian stylist of fascinating eloquence and virtuosity, sometimes sustains single high notes with transcendent, gleaming purity that irradiates the whole drama. The most multi-faceted singing of all is DiDonato’s: she can be vehement and quiet at the same time, both deeply compassionate and raptly inspired. The British tenor Ed Lyon (Didymus’s friend Septimius), the Polish bass Gyula Orendt(Valens), and the Royal Opera chorus all become vital elements.

Handel gave the premiere of Theodora at Covent Garden in 1750. As he guessed, it proved a flop, but one in which he believed. Now this 2022 production demonstrates his dramatic mastery. Until less than 50 years ago, his operas used to be staged as oratorios, exercises in dramatic stasis and as vehicles for park-and-bark acting. Now his oratorios – a genre to which he turned when opera proved too expensive - are being revealed as superb stage drama. Theodora is said to be his favourite among them, although it features none of his Greatest Hits. Although even in 1750 it had great admirers, it has only in the last 30 years entered into the operatic repertory, notably with the 1996 Glyndebourne and 2009 Salzburg productions – and now this one.

On Monday night, fans of great vocalism were out in force, immediately hailing Bullock, Orliński, DiDonato, and Lyon, after their most remarkable arias. Who could blame them? Yet Bicket’s seamless pacing made it easy to feel that here, perhaps more than in any other work, Handel was thinking in gripping spans far longer than individual numbers. How gratifying: 272 years on, Handel the great Covent Garden dramatist has come into his own.

<Financial Times>

* * * * * *

The Cunning Little Vixen, English National Opera, 28 February, 2020

A vixen is the female of a species often regarded as predatory vermin. To turn such a creature into the enchanting, vivid, touching, poignant, naughty heroine of a three-act opera takes a fabulously subversive mind. Yes: the very mind shown by Leoš Janáček throughout his deeply entertaining and affecting The Cunning Little Vixen. This work, first staged in 1924 and a recurring work in British repertory since 1961, has just returned to London in a delectably fresh and inventive new production at English National Opera.

To witness it is to be made newly aware how this opera transcends its own subversiveness. Vixen - both delectably miniaturist and sweepingly multi-layered - is a life-enhancing tragicomedy. It’s about the cycles of life. Love, mating, parenthood, and death all become transitions within a larger process.

This production opened on Sunday 20 afternoon. (Friday 18’s original opening had been canceled due to Storm Eunice.) It’s the first creation for the London Coliseum by the director Jamie Manton, who has previously directed operas for smaller spaces. Here, he takes to this large stage with assurance. Rather than create a single natural world in which animals and humans co-exist, he and designer Tom Scutt have given us a staging that’s about stories and story-telling – about metafiction. One narrow line of painted decor unscrolls as it descends to the floor, sometimes echoed by other vertical but static strips of décor, all depicting the forest at different times of day and year. Five other scenic components - tall horizontal boxes - are moved and revolved about the space. At the back, a door, sometimes opening onto piercingly white light, suggests a whole new plane of unknown reality beyond this stage realm. (Lighting is by Lucy Carter.)

All this accords with the current version of the translation by Yveta Synak Graf and Robert T. Jones. Where Janáček (who wrote his own libretto) adds a touch of narrative complexity by referring at the end to the newspaper serial from which he took his story (a human character cautions a junior vixen “so that people won’t write about you in newspapers”), this English account goes further: it has him sing of making “our life into an opera”.

This is at least one more level of artfulness than Janáček had in mind. And yet this opera’s beautiful innocence is maintained: Manton and Scutt never untell its story by over-cleverness. They make the animal characters great fun; likewise the anthropomorphic mushrooms and (most) insects. The Cock is a particular triumph, splendidly attired in a glossy tall vermilion crown (with matching red eyelashes and eyebrows), a rainbow-spectrum jacket, shining black baggy pantaloons over bright yellow boots. (The only ingredient that doesn’t work is the hunched, pedestrian body-language of the Dragonfly.) Sally Matthews – bright of eye and voice alike – has all the energetic swagger, irrepressible defiance, and, yes, the tender, naïve heart for the title character. The human characters are all physically slower and, fascinatingly, less spontaneous.

Janáček’s vocal lines often make it hard (harder, in my experience, in this opera than in others) for singers to make any English translation register; I was often grateful for the English surtitles. Still, the experienced tenor Alan Oke (Schoolmaster and Mosquito) and the young bass-baritone Ossian Huskinson made their (apparently effortless) diction telling, while Matthews certainly made most words count. As the Fox, Pumeza Matshikiza often showed the most gloriously burnished vocal sound of all (and great facial charm), but she too often sang under the note and with unintelligible words. As the foremost human character, the Forester, the baritone Lester Lynch has both power and lyricism. Still, there are many passages in which he begins to bray, as he forces to make an important sound.

I’m not convinced Martyn Brabbins is a singers’ conductor. While everyone sings on cue for him, no English National Opera idiom emerges – whereas I remember how Reginald Goodall and Charles Mackerras elicited particular styles from their casts. He nonetheless catches many macro- and micro- aspects of the score: delicate chamber details, gripping symphonic architectures. On Sunday, a big ovation greeted every participant. The spell begun by Janáček pervaded the Coliseum.

<Slipped Disc>

* * * * * *

Peter Grimes, Royal Opera, 18 March, 2022

Benjamin Britten’s first opera, Peter Grimes (1945), is one of the great works of the human spirit. A masterpiece of compassion, alienation, poetry, seascape, humour, humanity, tenderness, satire, soul, anguish, and despair, it has inspired a wide range of good and great productions. Britten went on to make works of yet greater sophistication and imagination, but in no other opera did he so marvellously fuse many strands into knockout theatrical power. For me, this is home music; I myself grew up close to the East Anglian coast Britten knew and evoked so well. But I’ve known Grimes make profound impressions at the New York Metropolitan Opera and at Glyndebourne. My experience of it goes back to the late Elijah Moshinsky’s legendary Covent Garden production, which I watched twice when new in 1975 (I was a rapturous nineteen-year-old) and several more times in succeeding years.

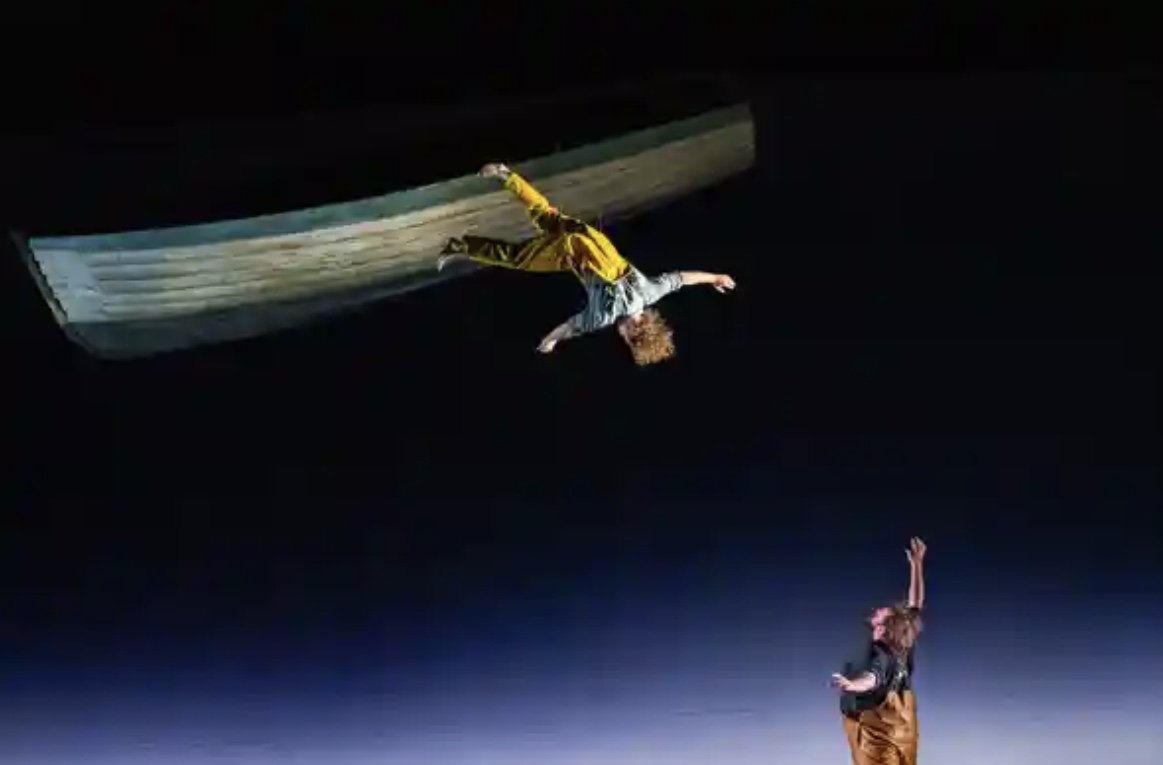

Watching Deborah Warner’s new, modern-dress, Royal Opera production on Thursday 15, I marvelled that this opera could be reinterpreted in wholly terms. Some of this staging’s imagery will, I hope, stay with me for the rest of my life. The opera’s Prologue, a town inquest that introduces us to the tragic Grimes and to his many quasi-cartoon neighbours, here is staged as the recurring nightmare of a Grimes who is drowning or indeed long dead. Horizontal on the floor, wrapped in the fishing nets of his profession, Grimes (Allan Clayton) rolls and rolls across the stage. The townspeople, tall silhouettes en masse, loom behind him and pursue him like phantoms. Individual faces are suddenly illuminated like grotesque Daumier caricatures. This suggests that Grimes’s torments will find no peace even in death.

Another drowned man also haunts this production: the apprentice fisherman who died while Grimes and he were at sea, the object of that Prologue inquest. But whereas Grimes in that first scene is floorbound, tossing and trapped, the ‘prentice is a soaring vision, seen only by us and Grimes. He floats down and up through the air, spinning slowly, helplessly, flotsam and jetsam, a helpless corpse forever gesturing for help.

The second time this ghost appears is in the pub scene at the end of Act One. The locals are all joining in the vivid canon of the marvellously stirring shanty “Young Jo has gone fishing”, but Grimes, seeing his dead apprentice high above them, adds a new vocal line in a vein of searing pain, cutting through the intricate ensemble with tragic perception. Peter Mumford’s lighting catches the many strands of this difficult pub scene as beautifully as, in Acts Two and Three, he catches the glitter of the North Sea’s waves.

The most strangely marvellous element of Britten’s opera is that its protagonist is also a poet. In this production, when he enters the pub, he turns his face to the door – his back to us - as he sings his most visionary words of all (“Now the Great Bear and Pleiades”). His thrilling alienation is all there in his inability to connect with the village community and in his need to describe the despair of human fate (“Who can turn skies back and begin again?”).

At Covent Garden, this is also a peak moment of music. Britten wrote the role of Grimes for Peter Pears, whose skills included the ability to enter, head-on and piercingly, the most exposed upper notes in the tenor register but without the power of chest voice. These were the antithesis of what suited the searing Jon Vickers, the dominant Grimes from the late 1960s to the mid-1980s, whose chest tones were the very stuff of heroism; the heaving strain he brought to these lines remains unforgettable but far from exemplary. Allan Clayton, amazingly, combines much of Vickers’s dark chest power and Pears’s cleanly incisive attack: a superlative amalgam, combined with lucid diction, that makes Clayton a classic twentyfirst-century Grimes – and makes Britten’s opera new again. Another astonishing feature is that Clayton’s physique is not honed. He looks ungainly, a misfit, and yet physically expressive at every moment: we share his feelings by watching him.

The marvels don’t stop there. The cast contains two of the supreme interpreters of Wotan in Wagner’s Ring Cycle: John Tomlinson as Mr Swallow, Bryn Terfel as Captain Bulstrode, wonderfully authoritative figures who add terrific scale and generosity to this Borough tale. Maria Bengtsson, playing the schoolmistress Ellen Orford in jeans and sweater, sings this complex role (both compassionate and bleak) with a luminous beauty that often evokes the classic performance of the superlative Heather Harper on this same stage. Every character is individualized.

Mark Elder, conducting, makes every colour and line of this drama register, gleamingly. The Royal Opera Chorus doesn’t sing the witch-hunt calls of “Peter Grimes!” with the terrifying power it did under Colin Davis decades ago. At all points, however, this music lives from within.

<Slipped Disc>

@Alastair Macaulay 2022

1:Peter Grimes, Covent Garden, March 2022

Allan Clayton, right, as Peter Grimes. Jamie Higgins (aerialist), left, as his dead apprentice. Photograph: Tristram Kenton.