Patricia Lent (Part One) on Merce Cunningham

Patricia (“Trish”) Lent danced with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company for ten years, from 1984 to 1993. She went on to dance with Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project in 1994-1996. In 2002, she was invited by Cunningham to revive Fabrications (1987) for his company, a project she brought off with great success. A month before his death, Cunningham announced plans for his artistic legacy that included appointing four people to the Cunningham Trust. One of the four was Lent, who became Director of Licensing.

By chance, Lent was the first Cunningham dancer I ever met, when the company toured to Leicester in 1989. The dancers and London critics were invited to the same meal; Lent broke the ice by asking me about my having worked in New York the previous year. Without ever becoming close friends, we have had conversations – largely but not only about Cunningham – ever since.

During Cunningham’s lifetime, very few of his colleagues ever saw any of the preparatory notes he kept for almost all the dances he had made. These are fascinating, but should probably not be seen as scores from which the dances may be reconstructed. Lent’s studies of these notes – a project she has been involved in for many years – has been incomparably searching. In New York, between 2012 and 2017, we collaborated a number of times on presentations of individual Cunningham dances: I learnt much from her on each occasion.

We conducted this questionnaire by email. We both very much hope to address further questions in due course. AM.

AM1. Dance “happened” to you in childhood; I remember, for example, your telling me of your admiration for the British ballerina Merle Park. What kinds of dance? Can you say how it or they prepared you to enjoy Cunningham?

PL1. I started taking ballet classes when I was three years old at a local dance school. It was recreation really, with annual recitals– one year I was a butterfly, another year a bumblebee. I loved it. After a few years, I switched to a more serious school and became increasingly devoted to ballet, and especially devoted to my teacher Edward Caton, who taught at the school for a year or two. With one hiatus, I continued to dance through high school – mostly ballet, but also some jazz and modern dance classes, and I pretended to tap in a school musical. I had professional aspirations – I spent one summer at SAB and another at Pennsylvania Ballet, but eventually got discouraged, quit dancing “forever,” and went to college at the University of Virginia.

UVA had no dance program at that time, but in my junior year Nora Shattuck (formerly Nora White of Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo whose husband was the chairman of the French Department) began teaching elementary ballet and modern dance classes. She became my teacher and my friend, and she encouraged me to continue dancing.

And so, after I graduated, I spent the summer at American Dance Festival, and then tried dancing in Boston for a couple of years.

Finally, in 1982, I moved to NYC with the intention of studying at the Merce Cunningham Studio (which I had heard about but never visited) and with Larry Rhodes (who I had studied with at ADF). My plan was to train intensively for a year – to get better or to quit “forever” again. Eighteen months after I arrived in New York I was asked by Merce to be an apprentice (this was before there was a RUG program), and in January 1984 I joined the company.

I never saw the Cunningham company perform until March 1982, a few months before I moved to NYC. But while I was growing up, my mother brought me to see a lot of dance, both ballet and modern dance. She was a big theatregoer.

AM2.Cunningham dance theatre is larger than Cunningham. It opens onto Zen, onto Dada, onto radical modernism, onto multiple forms of theatre, onto Duchampian, Cagean, and Rauschenbergian aesthetics. Some Cunningham dancers arrived with some grounding in some of these. Do you feel you had some prior connection to, or appreciation of, any of these?

PL2.I had some grounding in visual arts – visiting museums in Washington DC during my youth and taking art history classes in college. I also saw a fair amount of theater growing up, and studied literature and theater in college. I knew very little about Cage/Cunningham but was familiar with the work of some of the artists and writers they associated with.

AM3.Did you first experience Cunningham as a classroom technique or as a theatrical experience? Please describe.

PL3. When I moved to Boston in 1980, I studied with a woman whose classes were described as “Cunningham based.” I didn’t really know what that meant, but I enjoyed the classes. After two years of getting nowhere in Boston, I decided to give NYC a try before giving up once and for all. In preparation for moving, I visited the city for a weekend in March 1982 with some friends who were also planning to relocate. That’s when I saw the Cunningham company for the first time, at City Center. They did Channels/Inserts (1981), Gallopade (1981), and something else.

I loved the performance – for its vigor, for its clarity, for its power. I realized that, to do the kind of dancing I admired, I needed to be a better dancer, and so I made a plan to spend one year training in NYC – ballet every morning, Cunningham every afternoon. I took my first Cunningham class the day after I arrived (June 1982) – the 6:00 Elementary class. My first teachers were June Finch and Diane Frank.

AM4.Which teachers other than Merce best opened your mind and body to Cunningham dance as a discipline?

AM4. Susana Hayman-Chaffey was a very prominent teacher when I first came to the studio. She taught the 4:30 Intermediate class nearly every Tuesday and Thursday. Her classes were intensely challenging both for the body and mind.

Meg Harper and Chris Komar were probably my favorite teachers. I responded to their keen sense of rhythm and timing. Meg’s classes had a special kind of spirit – inviting and intriguing – as though we were all in it together, dancing and discovering. What I especially remember about all the classes at Westbeth was how invested everyone was – dozens of us, dancing, dancing, dancing.

AM5.How, in your experience, did Merce differ as a teacher from others teaching his technique?

PL5. Merce was more demanding than any other teacher. He asked us to do things that no one else could or would. What he gave was slower, faster, more technically challenging than anyone else’s. The combinations weren’t especially complicated – although often rhythmically complex. The difficulty often had to do with getting from one position or movement to the next – the transitions were devilish or non-existent, almost undoable. He spent no longer than was absolutely necessary to teach the material, so we were dancing for almost the entire duration of the class. I found his classes both invigorating and excruciating.

AM6.What (if any) Cunningham dances did you most admire as an observer before you joined the company?

PL6. Channels/Inserts, Quartet, Trails. I hadn’t seen many performances before I joined the company, just City Center(one show in 1982, several in 1983), and a series of Events at the Armory. I had done several workshops – some of which were taught by Merce – which gave me more insight into the work.

AM7. As a White Oak dancer, you once sent me a hilarious postcard saying (words to the effect of) “I’m figuring out how to time movement to music, but will someone now tell me why?” But your pre-Cunningham experience of ballet and perhaps other genres showed you various kinds of musicality, and your Cunningham experience of classroom technique classes showed you how music and Cunningham technique can work satisfyingly together. Do you remember any difficulty or challenge in learning to be independent from music?

PL7. I consider myself to be a rhythmically strong dancer and teacher. For me, one of the most appealing and satisfying things about Merce’s work is its inherent, musicality, which exists in the movement itself rather than as reflection or amplification of the music. In Merce’s choreographic work, the dancers are responsible for realizing and embodying the rhythm and phrasing. We make it visible. That is a source of great satisfaction for me. The choreography was taught without music, so we didn’t have to adjust to music being “taken away.” The music – in the sense of rhythm and phrasing – was baked into the movement.

The challenge for me when I joined White Oak wasn’t rhythm or musicality per se. I had had plenty of experience dancing to music in daily classes for years and years. That was something I greatly enjoyed. The challenge for me was learning to listen for aural cues in the music – a violin, let’s say, or a particular chord or melody. I had to develop that skill.

AM8.A number of Cunningham authorities describe individual works or dancers or phrases as being musical or rhythmical or (Merle Park’s adjective about herself) phrasical. Can you say where you have most felt musicality (or rhythmicality or phrasicality) in a Merce work or dancer or sequence?

PL8.In my experience, rhythm and phrasing are integral to all of Merce’s work. Not all the work is metric – as in countable or regular – but it all has strong, distinct timing and phrasing. Dances in which I especially enjoyed embodying the rhythm and phrasing include (in no particular order) Roaratorio (1983), Doubles (1984), August Pace (1989), Fielding Sixes(1980), Change of Address (1992), Fabrications (1987), Exchange (1978), Native Green (1985).

AM9. You have spoken of the “song” in a Cunningham dance. Other Cunningham dancers do too, but not all. Did you ever hear Merce use the term? (Bonnie Bird, his first modern-dance teacher, spoke of the way the Northwest Native Americans would find the “song” of their amazing dances, which were largely solos. She and Merce had both had particular access to one tribe north of Seattle, Merce more than she.)

PL9. When I use the word “song” I’m not talking about a melody or a mood or anything like that. I’m talking about a vocalization of the rhythms and phrasing of movement – including accents, dynamics, tempo changes, etc. I don’t know whether or not I ever heard Merce use the term “song,” but I heard him “sing” in rehearsal and in class (for years he taught with no accompanist) for all ten years I was in the company. This happened when material was being taught – he would use his voice and hands (clapping, beating) to transmit the phrases to us. Over time the “sound” of a phrase became an internal song which we “heard” while we danced – albeit each in our own way. When Cunningham dancers say they don’t remember the steps anymore, but they still remember the rhythm, that’s what they’re talking about. Once the material was learned, Merce stopped vocalizing/clapping – it became our responsibility to maintain the phrasing & timing. And, in any case, if there were several dancers on stage doing different things – which happened most of the time – we were rarely doing phrases that shared the same rhythm or meter (if there was a meter).

What many of us do now as stagers when we teach choreography is to try to replicate that process, that experience. This is not unique to Cunningham work – lots of dancers and teachers and choreographers vocalize rhythms and phrasing. What is different is that the rhythms and phrasing in Merce’s work are not reflected or echoed or supported by the music. The dancers have to learn to realize the rhythm and phrasing independently.

AM10. When some Cunningham dancers say they don’t think of “song” in Cunningham choreography, I guess it’s because, as in ballet, every dancer has to find her or his own musicality: some sing their dances, some count them, and so on.

But could this also be affected by individual works? In your experience, did every work involve “song”? Or were some rhythmic without being melodic ?

And were others to do with other games with time? Were there multiple musicalities in Merce’s work, some of them not really involving song/melody?

PL10. Melody doesn’t play a part in it all. Each phrase of movement has its own rhythm, or “song.” Most phrases last less than a minute, and then you’re on to a different phrase with a different rhythm. Some phrases are easily countable,some aren’t. Often the counts fall away once you’ve internalized the phrasing.

And sometimes, especially in the some of the later dances I did – for example, Loosestrife (1991) and Enter (1992) - Merce instructed us to disrupt the phrasing – to do a phrase “differently each time,” meaning to alter the tempo & phrasing.

AM. I’d say I use “melody” as synonymous with – or close to - “song”.

PL. Ah, I see. I probably use song as more or less synonymous with (augmented) percussion.

AM11. What you say about Loosestrife and Enter is so interesting. "Merce instructed us to disrupt the phrasing – to do a phrase ‘differently each time,’ meaning to alter the tempo and phrasing." Can you enlarge? Did he leave the differentiation up to you? And did he want all these differences to have a "disruptive" effect?

PL11. He didn’t use the word “disrupt,” that’s my word, and it’s possibly misleading.

He said “do it differently each time.” By which he meant not changing the actual steps, but changing the timing. So that it was the same phrase but differently phrased. Some of this may have been almost imperceptible, but to me it lent a kind of eccentricity to the timing.

One last clarification — often this happened when a short phrase was being done several times in a row. The idea was to repeat the same phrase, say, three times, but to each time with different timing.

AM12. Thanks partly to you, I have come to think of Merce’s choreography as a form of music-making. When some Cunningham dancers seem “musical” to you, can you say what qualities you’re observing when? David Vaughan often spoke of how acutely musical some Cunningham dancers were, but I never got to ask him whether he was talking about how they used Pat Richter’s music in class or whether he found that musicality in Merce’s choreography. Your thoughts?

PL12. I would say it was both how they danced in class and how they danced in the choreography. But especially in the choreography when the dancer can’t rely on musical support. Some dancers, as you watch them, seem to embody and realize the phrasing. You can “hear” what they’re doing by watching them. You can glean the rhythm without knowing what it is or connecting it to what is happening in the music. For me, Merce’s work is especially satisfying to watch (and even more so to do) when there’s a clarity and expansiveness of the form (shape, line, etc.) existing within a web of rhythm and timing. It’s all there, movement in time and space.

AM13. Many Cunningham dancers from Carolyn (Brown, 1953-1972) and Viola (Farber, 1953-1965 and 1970) onward chose to supplement their Cunningham classes with ballet classes - Margaret Craske, Antony Tudor, Janet Panetta, Maggie Black. Did you? If so with whom? How did it help you?

What was it like for dancers who took Cunningham classes alone?

PL13. I took ballet almost every morning except when we were on tour. On days when Merce taught company class (Mondays Wednesdays Fridays at 11:30), I usually took barre and adagio and then dashed over to the studio. On Tuesdays & Thursdays when there was no morning class, I took a full ballet class and then came to rehearsal.

My first NYC teachers were Larry Rhodes, then Ernie Pagnano, then Marjorie Mussman, all of whom were marvelous teachers and all of whom helped me improve in various ways. I found my way to Maggie Black’s class in the mid/late 80s and stayed with her until I stopped dancing. Her teaching was invaluable to me.

Maggie’s class set me up for the day – her class got everything going, it got me placed and warm, and helped me feel ready and confident (or alerted me if something wasn’t working so well that day). Over time, her class made me a stronger, cleaner, more expansive dancer. The other huge benefit was that I became part of a diverse community of professional dancers – everyone was touring here and there, working with different choreographers, but every morning those of us in town came together in Maggie’s class. It was a “non- virtual” chat room before social media existed. The Cunningham company could be an insular place, so having an alternate community was refreshing.

AM14. Two superb dancers left MCDC (Merce Cunningham Dance Company) around the time you entered the Cunningham orbit: Robert Kovich, Karole Armitage. Did you observe them or encounter them? (Kovich taught, I know.) What do you remember, and what if anything did you take from them?

PL14. I took a few classes from Robert Kovich, and I saw at least one performance of his work in a small space in NYC. But I didn’t have much contact with him. He was a marvelous dancer, but I didn’t have the impression he especially liked to teach. I auditioned (unsuccessfully) for Karole Armitage before I joined Merce’s company. I saw here dancing in her own work in NYC. I never saw either Robert or Karole dance Merce’s work except on video.

AM15. Chris Komar was another great dancer who was probably still at his peak when you joined MCDC. What did you admire about his dancing?

PL15. For me, Chris was all about rhythm in space. He had a playful approach to meter and phrasing, and a practical approach to Merce’s work. He knew how to live inside the work. He always seemed so comfortable and sure.

AM16.Robert Swinston has often said that Kovich and Komar achieved a speed in Cunningham material that was an all-time peak, which he was never able to equal himself or to train others to equal. Do you agree?

PL16. I know that they were both admired for their footwork and overall technique, and Kovich especially for his jump. During my time in the company, movement got faster and faster both in class and in the choreography. Merce said it had to do with dance on film, and how the eye catches things quicker, so that the dancing needed to be sped up. From what I saw, his work continued to get faster and faster after I left.

AM17. Another highly important dancer of your early years was Catherine Kerr. What did you admire about her?

PL17. Cathy could cover space in a remarkable way. Everything she did was large and expansive. I admired the power and breadth of her movement.

AM18. Cunningham dance theatre both gives much identical material to men and women and much specifically masculine/feminine material to each sex. Please say all you can about this. It’s my impression that one of the many ways Merce was radical in the 1950s was his ways of making men and women share material and costume. Do you agree? But did you ever feel (as Carolyn Brown has sometimes complained, perhaps not very seriously) that Merce had invented a technique and style that suited men more than it did women?

PL18. In class, we all did the same phrases, and we were all responsible for executing a wide range of movement to the best of our ability – adagio, balances, turns, fast footwork, jumps, etc.. Everyone had their strong suits. I loved to jump, I loved rhythmic complexity, and I loved phrases that travelled swiftly through the space. I did a fair amount of that kind of movement in the choreography, but, like most women in the company, I also spent oodles of time balancing on one leg while a man, or a bunch of men, jumped or sped around me. I know that the movement we women did served a choreographic purpose, but it could be brutal to do. It required a great deal of control and strength. The men, on the whole, seemed to have more opportunities for abandon. I was thrilled when Merce made August Pace and Change of Address because in both those dances I was given big, bold, athletic movement to do – I got to do the jumping and speeding around.

AM19. As you know, some observers still talk as if the glory that was Cunningham principally resided in the 1953-1972 generations: some of them feel it ended when Carolyn Brown left the company, others when Merce’s own use of the back changed (they feel) in the 1970s. To them, such dancers as Chris Komar, Catherine Kerr, Robert Kovich, Karole Armitage were Silver Age. We can’t change their opinions, but can you, from your perspective, now say what were the most valuable ways in which you feel Merce after (say) 1972 went on growing as an artist?

PL19. This is a very big question. Perhaps I’ll begin by stating the obvious – the most thrilling and fulfilling period for a Cunningham dancer is the period when they are in the company themselves. Being inside the work, and part of the creation of the work, is an entirely different experience than sitting and watching the work. There’s simply no comparison.

One idea I firmly dispute is that Merce’s physical limitations as he aged limited the kind of movement he could make. That’s simply not true. He was a master at inventing movement and in conveying that movement to his dancers. He had a miraculous ability to “demonstrate” movement without fully embodying it, and to push his dancers to inhabit the movement boldly and fully. If anything, I would say that, as he aged, the movement he invented was increasingly complex and challenging – his own body did not limit his imagination or the demands he placed on his dancers.

There were certain dances, and perhaps certain periods, in which Merce was prioritizing some aspects of the choreography more than others. Some dances that pushed the speed and complexity, others that pushed athleticism, others that were more languid or lyrical or waltzy. But my experience was that at any one time, the repertory encompassed a wide range of movement.

One of the features of my time in the company is how prolific Merce was. We were touring and performing a great deal, and he was making on average three new dances a year and as well as working on film projects. I would say he was pushing complexity in all its facets – the intricacy of the movement, the structure of the dances, and the way he used the space. It is remarkable how he moved 15 dancers through and around the space in ways that were unpredictable, and yet ended up seeming inevitable.

AM20. Are there certain ways in which you agree with those people, certain factors in which, when looking at 1953-1972 footage of Cunningham dancers and Cunningham creations, you think “The later generations may have had different virtues, but they could never equal THAT.”? I, for example, would cite Carolyn Brown’s solo in Variations V (1965) and her amazing slow lifts of the leg from fourth position - and her whole solo - in Walkaround Time (1968).

PL20. I have been astonished and moved by dancers before my time, during my time, and after my time. When the company was smaller, the choreography did seem to focus more on individuals. Once the company expanded to fifteen (a few years before I joined), Merce’s work dealt more with groups and groupings. Carolyn was indisputably a stunning dancer, and I’m sorry I never saw her perform live. But there are many other Cunningham dancers who were thrilling to watch, who made me gasp – Susan Emery (MCDC 1977-1984), Helen Barrow (MCDC 1982-1993), Derry Swan (1996-2004), Jean Freebury (1992-2003), Andrea Weber (2004-2011). And that’s just some of the women.

AM21. Early MCDC dancers were exposed at close quarters to the Cage/Rauschenberg/Duchamp aesthetics because Cage, Rauschenberg et al. were around. Cage was certainly around in your day, but seldom with the same intimate connection with individual dancers. Did members of your generation have to work to understand those aesthetics and principles? I remember Swinston in 2000-2009 saying that he found himself teaching the younger dancers those things.

PL21. Cage was part of the touring group when I joined, and so I had a sense of what he was like at that time in his life. But I didn’t interact with him socially, and the company was not the intimate group it had been in the early years. I did try to educate myself about Cage and his work – reading, going to concerts, exhibitions. I remember finding Elliot Caplan’s documentary helpful inexpanding my sense of that circle of collaborators and friends. I did the same for Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Duchamp. I read about their work, I went to exhibitions, I listened to stories told by others.

AM22. Merce was a great dancer till the end, but he was in his sixties when you came along. In what pre-1973 roles do you feel he seems to have been most exceptional?

PL22. Of course I only know Merce pre-1973 from video. He’s stunning to watch in Changeling (1957), Suite for Five (1956), Night Wandering (1958), Second Hand (1970), RainForest (1968).

AM23. In what ways did you feel Merce differentiate between men and women? Personally, choreographically, stylistically?

PL23. In Charlie Atlas’s documentary, Merce says:

“I prefer having the possibilities that a woman gives in movement as well as the possibilities a man gives, and they are in one sense the same, but they’re also different. Women so often to me have a kind of continuous quality which can go on really for quite a long time, whereas with the man so often it seems in spurts up and down.”

This captures my sense of how Merce thought about gender in dance – in one sense women and men were the same, but they’re also different. Whether or not his particular characterization of their qualities (continuous vs. spurts up and down) holds true for others, I do think he thought of male and female dancers differently. And, as in all his work, it was his inclination to push the differences rather than smooth over them.

AM24. At other times, it was felt that Merce’s best “friend” in the company or around the school would be a woman who wasn’t psychologically needy: examples are Marianne Preger (whom Cage once called “the soul of the company”), Margaret Jenkins (whom Cage once called, saying “You know everything about Merce, he tells you everything”, though she said Merce didn’t), Valda Setterfield. Maybe to a lesser degree Lise Friedman; one person feels Merce was also comfortable that way with the quiet Helen Barrow. Any comments on this?

PL24.In my time (and for many years afterward), the female dancer Merce seemed most comfortable with and closest to was Meg Harper. I had the sense that he trusted her. Two other women he seemed especially close to – not company dancers - were Bénédicte Pesle and Sage Cowles.

AM25. Merce tended to focus on the newest member of the company, working to strengthen or develop her/him. Was this true with you? What do you remember?

PL25. Merce’s eye was attracted to change. I’ve always felt that he asked me to join his company not because I was the best dancer at Westbeth at that time, but because my dancing was changing. New dancers are often the ones most evidently undergoing change – the technique and the work are powerful agents for change.

So, yes, I felt that Merce focused his attention on me at the outset (not all of his attention, of course, but some). I think he gave me things to do that he knew would help me grow, and that were a little over my head. For example, Lise’s solo in Doubles (after she left), and Susana’s solo from Signals (which he often used to challenge young women in the company). He made Native Green when I was quite new, and that dance, with its small cast, was a privilege and an adventure.

AM26. At some point - sometimes after the first six months of a dancer’s joining the company, sometimes after three years - Merce’s attention would be so fixed elsewhere that the dancer felt she/he was cast into outer darkness or was invisible to Merce. (My own guess was that Merce wanted each dancer to learn how to hold her/his own without psychological dependency on him or needing to please, but I bet it was disconcerting to go through for some dancers.)

Did this happen to you?

PL26. To some degree. Overall I was very fortunate in the material I was given to do, especially in the new work (which was what interested me most). But certainly I felt his attention wane after the first few years. It wasn’t an entirely negative experience, as I had the sense that he trusted me to carry on with the work. He was a very busy man – teaching, choreographing, performing himself. He needed dancers who could take care of themselves. Merce and I also connected through teaching – he let me know that he liked my classes and considered me capable of teaching both technique and repertory. I was very invested in that side of things.

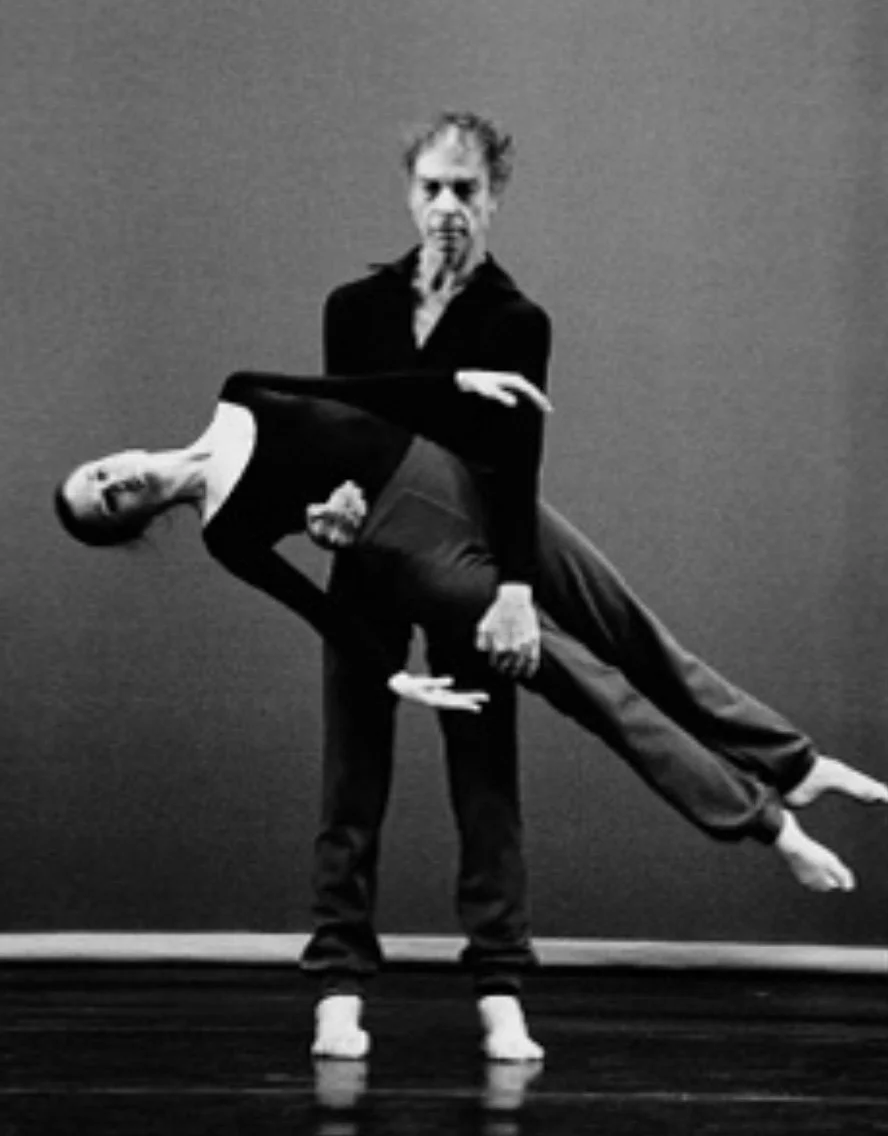

AM27. Merce’s work shows that he was pretty damn interested in every dancer at various stages of their careers. You were the woman he lifted at the end of Pictures (1984), the woman with the spectacularly risky duet in August Pace (1989), the woman with the fabulous slow zigzag solo in CWRDSPCR (1993), and with many roles in between. Which roles did you appreciate most, and in which roles did you feel Merce challenging or extending you best or most?

PL27. My role in Pictures was almost accidental. Merce had already started making the dance when I joined the company. I got added in. But it was a pleasure to do over all those years, first as the newest person in the company, and by the end one of the senior dancers. Leaving aside the roles I inherited from someone else, the dances Merce made for me that I especially appreciated – which were also the ones that challenged me the most – were:

Native Green (1985);

Fabrications (1987);

Five Stone Wind (1988);

August Pace (1989);

Change of Address (1992);

Doubletoss (1993);

CRWDSPCR (1993);

Revivals or inherited roles: Roaratorio (1983), Exchange(1978).

AM28. Still, you had to coexist with Vicki Finlayson, whom he once described – to none other than Carolyn - as “the real McCoy”. What was this like? Did you see Merce adjusting his teaching to suit her? Did you learn by competing with her?

PL28.Merce loved Vicki’s dancing, for good reason. She was an exquisite dancer. I don’t recall him adjusting his teaching to suit her, but he clearly singled her out in the work, and he took advantage of her penchant for slow movement. Competition was part of the ethos of the company. I think Merce stirred up competition on purpose. I was competitive, sometimes more so, sometimes less so. I’m not sure I learned anything from it. It was more a matter of surviving in spite of it.

AM29. Vicki in due course observed (without pleasure!) Merce adjusting his teaching to Frédéric Gafner (as he then was), allowing him to stay up in the air longer. It’s possible that “Freddie” (Foofwa d’Imobilité, as he became) was the single MCDC dancer Merce found most phenomenal in the whole history of the company. What was it like to watch and work alongside this new paragon?

PL29. Frederic was amazing to watch and amazing to work with. He took the principle of “making the movement all it can be” to the fullest limit. When Merce said to take a “big” step, Frédéric took an unimaginably big step. It was the same with everything he did – big, fast, strong, clear, expansive. And he brought so much joy and spirit to his work. Merce was mesmerized by Frédéric, and I also think he was invigorated and inspired. Frédéric breathed fresh air into the room. Westbeth was a better place to be after he joined.

AM30. You were part of Pictures, which was a special and immensely popular piece, regularly in repertory for some nine years, the work that received most performances in the company’s history. Beyond your own role, do you remember Merce creating its style with classroom teaching experiments? All that stillness and balance and calm slow motion?

PL30.The dance was already well underway when I joined the company. I’d only been in Merce’s class for a little over a year, and was still figuring things out.

AM31. Merce’s use of chance procedures is famous. Now that you have been posthumously studying his notes on a range of works, would you agree with me that he used chance, in one way or another, on almost every work after 1953? (Exceptions maybe included Septet, Banjo, Nocturnes, RainForest, Second Hand, Nearly Ninety, and maybe others, but few.)

PL31. I would agree, and Merce has said as much himself.

AM32. When - if ever - were you aware of Merce using chance procedures while you were dancing for him? (Most dancers either say “Never” or “Events”.)

PL32. I have memories of being in the studio outside rehearsal time – probably I was teaching class or a workshop – and he would be sitting at his back table flipping coins. I would think “He must be working on a new dance.” That would have been long before any rehearsals for that dance, and I would have had no way of knowing what the flipping represented (what questions he was asking or what answers he derived).

I don’t believe Merce ever used chance to construct an Event. He used chance to construct the material that made up Events. But the Events were built in a practical way to address practical needs.

AM33. In the years 1983-1986, you danced Inlets 2 and Roaratorio, the double bill Merce had made in 1983 just before you joined MCDC. This double bill was not the only time that Merce made two contrasting pieces at the same time: think RainForest and Walkaround Time in 1968, think Neighbors and Trackers in 1991. As you know, the notes for Walkaround Time and RainForest often occur on the same page of his notebook and are sometimes hard to tell apart, except for their being so dissimilar.

What does it say, to you, about Merce that he wanted to make such contrasting pieces at the same time?

PL.34. Merce was always working with contrast – both in developing programs, and within dances, and within his technique. But my understanding about Roaratorio and Inlets 2 is that the pairing was done for practical reasons. The original Inlets had recently left the repertory. A dance of twenty minutes or so was needed to open the program, and it had to be music that John Cage and the Irish musicians could play – Cage’s Inlets fit the bill. Rather than do the original Inlets (with six dancers including himself), Merce made a new version of the dance for two casts of seven dancers (not including himself). Originally (in his notes, but not in rehearsal), Merce intended to make two different orders for the beginning of Roaratorio, depending on which cast of seven dancers did Inlets 2 that night.

AM35. Inlets 2 is one of the classics that some Cunningham followers call his “nature studies”. David Vaughan did; I do.

Still, you are one of several who don’t. Do you find you had or have categories for Merce’s dances? For example, Ellen Cornfield told me she used to feel they fell into three groups: (a) the dramas (b) the funnies (c) those that “just were”. You?

I would add that, though some call RainForest a nature study, I don’t. To me the real nature studies (Summerspace, Inlets, Inlets 2, Beachbirds, Pond Way) are all really studies in Zen, but they all seem to be set in parts of the world unvisited by humans, whereas perhaps three of the RainForest characters seem human to me.

PL35. I don’t use the term “nature studies” because I never heard Merce use it. It’s a term used by people looking at his work, and one which implies that the viewer is perceiving something Merce set out to convey. I think Merce spent most of his life observing nature (including the nature of urban street-life) and that images and ideas from those observations made it into many, many of his dances. But I don’t think he set out to make a special kind of dance about nature. I think the dances that are categorized as “nature studies” get into that category in part because of a coincidence of movement, music, and design that makes them seem more “like nature.” The titles contribute to the effect, of course. I also know that observations about nature appear in the notes for many of his dances, some that would never be described as “nature studies.”

@Alastair Macaulay, 2022

1: The ending of Merce Cunningham’s Pictures (1984): Cunningham holding Patricia Lent. When Pictures was new, Lent was the newest dancer in the company

2: Merce Cunningham’s Fabrications (1987). Cunningham is on the left. The circle of four women jumping on the right has Patricia Lent (left, back to the camera), Helen Barrow, Victoria Finlayson, Karen Radford.

3: Lent in a teaching or staging situation in recent years