Visions of Cuba from Acosta Danza

Carlos Acosta has been many things: both Cuban and British, a superstar dancer, a novelist, a choreographer, a director of dance companies. The eleventh child of a family in one of Havana’s most impoverished areas, he went on not just to dance star roles around the world but to dance Yuri Grigorovich’s ultra-Soviet-Russian title role of Spartacus in Moscow with the Bolshoi and Frederick Ashton’s ultra-English La Fille mal gardée with the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden. After retiring from his onstage ballet career in 2016, in his early forties, he became director of the Birmingham Royal Ballet in 2020. His is an inspiring story of transcendence: when you see how his life has changed, you know those of others can, too.

While he was a principal of the Royal Ballet, he was a leading figure in taking that company to his native Cuba. In recent years, he’s done the reverse: he’s built a Cuban company that bears his name, Acosta Danza, and has brought it to the U.K. It danced at Sadler’s Wells in February 9-12; now it’s touring England – Salford (February 22-23), Hull (February 25-26), Canterbury (March 1-2), Plymouth (March 4-5).

Watching its programme of five works, 100% Cuban, I began by dismissing the company for churning out crudely ultra-sexy material. In the two works before the intermission Liberto, by Raúl Reinoso, and Hybrid, by Norge Cedeño and Thais Suárez – both popular with the audience - legs routinely zoom up above hip level, whereas feet seldom rise even to half-point.

After the interval, however, Pontus Lidberg’s Paysage, Soudain, la Nuit is a work of some poetry and sophistication that transforms the climate onstage and makes it specific. This is an ensemble work to Cuban landscape scores by Leo Brouwer and Stefan Levin (with some strains of rumba). The eleven dancers easily break and re-form into subgroups, their various geometries moving in harmonious structural polyphony. High extensions are contrasted with juicy footwork. The décor suggests a cornfield in late afternoon; the stage atmosphere is one of a rural idyll, with harvesters finding expansiveness after the day’s task. They’re not dancing for us; we seem to be overviewing a lovely local scene as if from the next field.

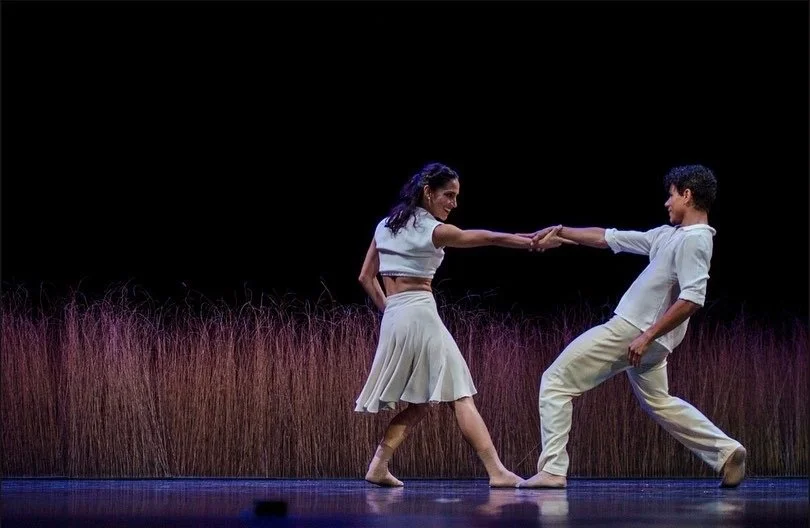

The solo Impronta, by Spanish choreographer María Rovira to music by Pepe Gavrilando, is a sustained (seven-minute) opportunity for the dancer Zeleidy Crespo to release her natural largesse of style and strong rhythmic sense. This isn’t important choreography, and yet Crespo’s dancing is important – and importantly Cuban.

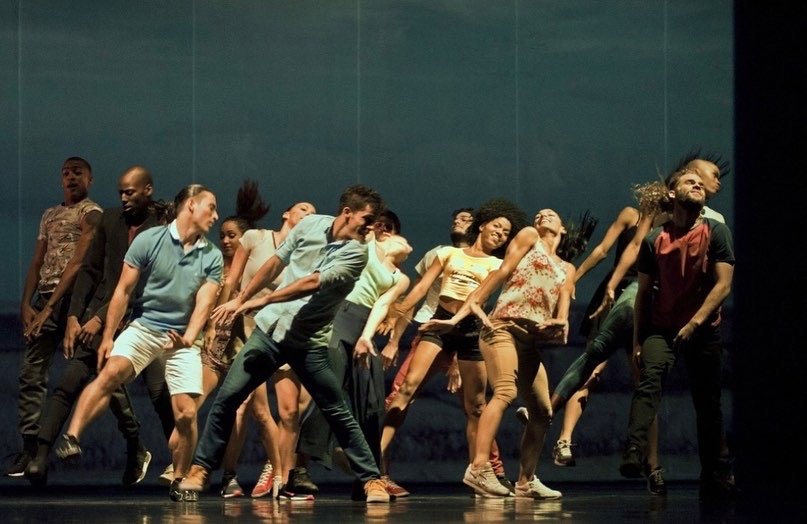

Something similar is true of the very different ensemble number that closes the programme, the eighteen-minute De Punta a Cabo, by Alexis Fernández and Yaday Ponce. The setting suggests the Malecón, the sea wall of Havana; the changing dance is largely high-spirited, blissfully ecletic in style, largely and exuberantly folk-related, infectiously charming in its evocation of Cuban young people. When three young women deliver fouetté turns on point, these aren’t some show-stopping climax: they too are part of the communal high spirits, no better than the longer duets, solos, and trios for other dancers. This is a relaxed group that allows prominence to some friends more than others without setting them apart.

These last three are visions of Cuba worth believing in. Their dancers are young, attractive, enthusiastic, natural performers all, taking pride in one another and in dance itself. They turn the greyness English winter into visions of sun, brio, generosity, community, rhythmic intricacy: warmth of many kinds.

@Alastair Macaulay, 2022

1: Paysage, Soudain, La Nuit, by Pontus Lidberg. Acosta Danza. Photo: Johan Persson.

2. Paysage, Soudain, La Nuit, by Pontus Lidberg. Acosta Danza. Photo: Johan Persson.

3: Paysage, Soudain, La Nuit, by Pontus Lidberg. Acosta Danza. Photo: Johan Persson.

4: Paysage, Soudain, La Nuit, by Pontus Lidberg. Acosta Danza. Photo: Johan Persson.

5: Paysage, Soudain, La Nuit, by Pontus Lidberg. Acosta Danza. Photo: Johan Persson.

6. Zeleidy Crespo in María Rovira’s Impronta. Acosta Danza. Photograph: Manuel Vason.

7: Zeleidy Crespo in María Rovira’s Impronta. Acosta Danza. Photograph: Johan Persson.

8: Acosta Danza in De Punto a Cabo, choreographed by Alexis Fernández and Yaday Ponce. Photograph: Hugo Glendinning.

9. Acosta Danza in De Punto a Cabo, choreographed by Alexis Fernández and Yaday Ponce. Photograph: Hugo Glendinning

10. Acosta Danza in De Punto a Cabo, choreographed by Alexis Fernández and Yaday Ponce. Photograph: Hugo Glendinning.