Alexander Kipnis: Advent Calendar of Song: Day Sixteen

Advent Calendar of Song: Day Sixteen

If there is a heaven, and if we get to it, and if we hear the voice of God, and if it doesn’t sound just like that of Alexander Kipnis (1891-1978), then I’ll be filing a complaint.

He grew up in a Jewish ghetto in Ukraine. He was twelve when his father died, after which he supported his family of seven by carpentry and singing as a boy soprano. Life and music took him, now a bass, to Warsaw and Berlin. During the First World War, he was interned as an alien in a German holding camp; but when he was heard singing there, he was soon transferred to the opera houses of Wiesbaden and Hamburg.

The 1920s and 1930s were his glory years: he sang at the Bayreuth Festival, the Salzburg Festival, the Berlin State Opera, the Chicago Civic Opera, the Vienna State Opera, Covent Garden, the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires, and elsewhere, in recitals and concerts as well as in opera. The accompanist Gerald Moore, who recorded with him, later recalled him as the finest musician among all the basses he had known; the list of great conductors with whom Kipnis worked is dazzling – Ansermet, Barbirolli, Beecham, Blech, Busch, Furtwängler, Karajan, Krips, Kleiber, Klemperer, Knappertsbusch, Koussevitsky, Mengelberg, Mitropoulos, Muck, Nikisch, Ormandy, Pfitzner, Reiner, Rosbaud, Scherchen, Strauss, Szell, Toscanini, Walter, Weingartner, inter al.. Along the way, he spotted Kirsten Flagstad, and made the introductions that gave that astounding singer her first international opportunities outside the Scandinavian region. He managed to stop singing in Berlin in 1935 when things grew dangerous for Jews, and then managed to stop singing in Vienna after 1937.

He had married an American; their son, Igor Kipnis, became a noted harpsichordist. Finally, the dozy New York Met signed him up in 1940 : thanks to that, we can hear him in the live broadcasts of operas by Mozart, Beethoven, Wagner, Mussorgsky, and Debussy. But he’s in live broadcasts elsewhere too, as in a live Beethoven Ninth with Toscanini in Buenos Aires and a small chunk of Gounod’s Faust in Vienna with the young Jussi Björling. He retired from the Met in 1946; his worst recordings from 1940-1946 there are better than those of almost every bass since 1950, but he then concentrated on recitals until 1951, when he retired and became a singing teacher. In spring 1966, there was a special farewell performance at New York old Metropolitan Opera House (the new Met opened at Lincoln Center that autumn) when company alumni took the stage: all the basses in the chorus rose as one when Kipnis entered.

When you listen to basses, there are four with whom you must begin: Pol Plançon, Chaliapin, Kipnis, and Ezio Pinza. Plançon (1851-1914) is light years from today’s basses, with a staggeringly suave sound, perfect diction, marvellous coloratura skills (trills, scales, flourishes), but – he made all his few records in his mid-fifties - he’s slightly sharp in some notes. His is a very French style: polished to the nth degree, and sometimes too gentlemanly, but deeply fascinating and brilliant. Chaliapin I’ve already included, sometimes the most outrageous of singers and often the greatest. Pinza (1892-1957), whose specialty was the Italian repertory, and Kipnis were exact contemporaries who appeared together at the Met in Don Giovanni (Pinza as the Don, Kipnis as Leporello); thanks to Pinza’s long contract with the Met, we have live recordings by Pinza of at least fourteen roles and many studio recordings beforehe entered on the most famous part of his career in 1949, creating the role of Émile de Beque in the Rodgers-Hammerstein South Pacific (yes, he created “Some Enchanted Evening”), winning a Tony Award, and becoming a national celebrity. Astonishingly, he, Pinza, did all this without being able to read music; he was abashed at the first South Pacific rehearsal when he realised that Mary Martin and other Broadway singers were using scores as he could not.

Don’t tell René Pape or Erwin Schrott – both of whom I love - but no post-1950 bass quite compares to these four. (I grant, though, that Boris Christoff transformed perception of the great role of King Philip in Verdi’s Don Carlo, as his records show.)

Kipnis is the most sheerly beautiful and musicianly of the four. With him, as with yesterday's Rosa Ponselle (yesterday), you have a dark voice that flowed like a mighty river. He was intelligent as well as musical: the role of King Marke in Tristan und Isolde is usually a bore, but becomes with him profound. He was a considerable vocal actor: funnily malicious as Osmin in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, dangerously powerful and psychotic in the title role of Boris Godounov. There is no voice I’d rather hear in Beethoven’s Choral Symphony; I’ve taken ages before I could bear today to exclude his account of the first of Brahms’s Four Serious Songs, where he takes us into zones of dark contemplation and legato utterance from the depths.

His recordings of the two arias by Sarastro in Mozart’s The Magic Flute (Zauberflöte) have always been classics. Beecham wanted him for his complete 1937-1938 Magic Flute recording with Berlin forces; but it was politically too late for Kipnis to revisit Berlin. This “O Isis und Osiris” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DwbRX9JKHho comes from 1930, with Berlin forces. Sarastro, welcoming the initiates Tamino and Pamina, invokes the gods to protect them as this hero and heroine enter the ordeals that lead to enlightenment.

Kipnis did not always sound noble, but oh! he does so here, definitively. Purists may question Kipnis’s use of portamento (especially the upward portamento - check “Gefahr” in the fourth line and “auf” in the eighth - sometimes thought to be unstylish in pre-1850 music); I think there’s one note that doesn’t register ideally; but the authority, beauty, and flow of this singing is sublime.

SARASTRO and CHOIR

O Isis und Osiris, schenket

der Weisheit Geist dem neuen Paar!

Die ihr der Wandr’er Schritte lenket,

Stärkt mit Geduld sie in Gefahr.

O Isis and Osiris, bestow

the spirit of wisdom on this young couple!

You who guide the wanderers' steps,

strengthen them with patience in danger.

CHORUS

Strengthen them with patience in danger.

Laßt sie der Prüfung Früchte sehen,

Doch sollen sie zu Grabe gehen,

So lohnt der Tugend kühnen Lauf,

Nehmt sie in euren Wohnsitz auf.

Let them see the fruits of trial;

yet if they should go to their deaths,

then reward the bold course of virtue:

receive them into your abode.

CHORUS

Receive them into your abode.

Exit Sarastro followed by the priests.

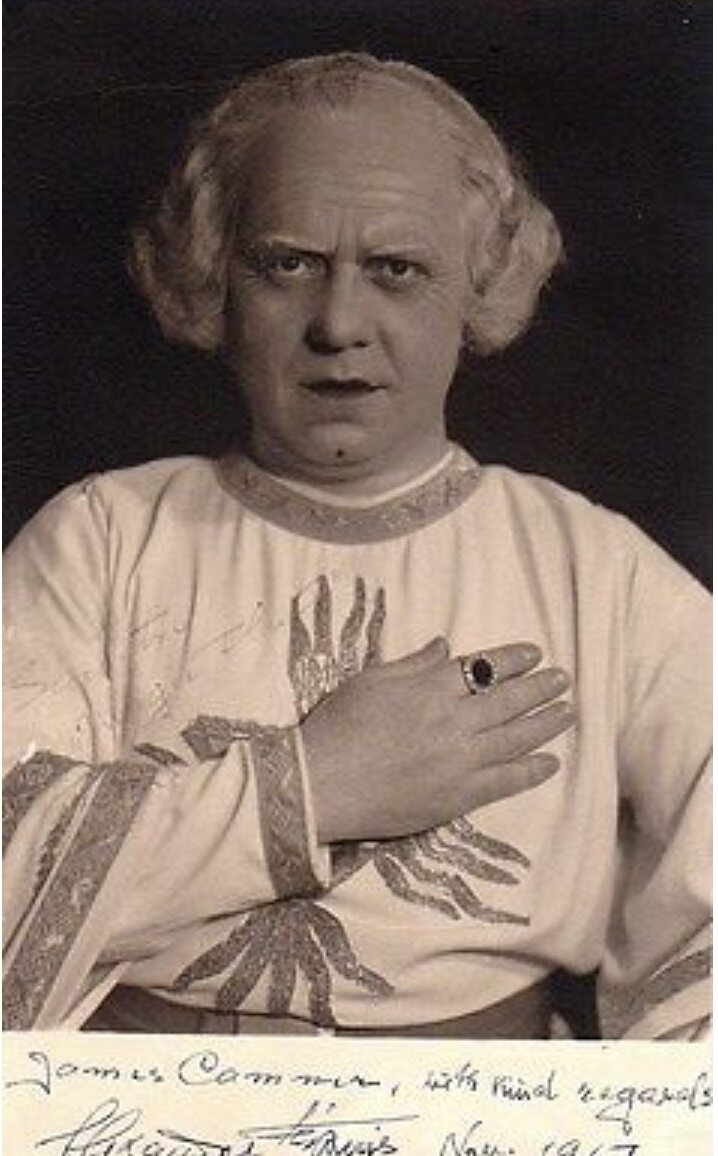

Alexander Kipnis as Sarastro

Alexander Kipnis as Gurnemanz in “Parsifal”