Swan Lake Studies 143-153

143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153 (in the “Swan Lake” series). The best motto in dance history is always “We Know Nothing”: something I well remember the Anglo-American critic Dale Harris (1930-1996) intoning in the 1980s. But even Dale found it hard to accept that some ideas of “Swan Lake” history were wrong; and I do too. Yet let’s just look in these eleven photographs at the opening few seconds of Odette’s adagio in “Swan Lake”: it’s bewildering how many discrepancies they reveal. The “Swan Lake” we’ve loved often proves to be less traditional and less historically correct than we thought.

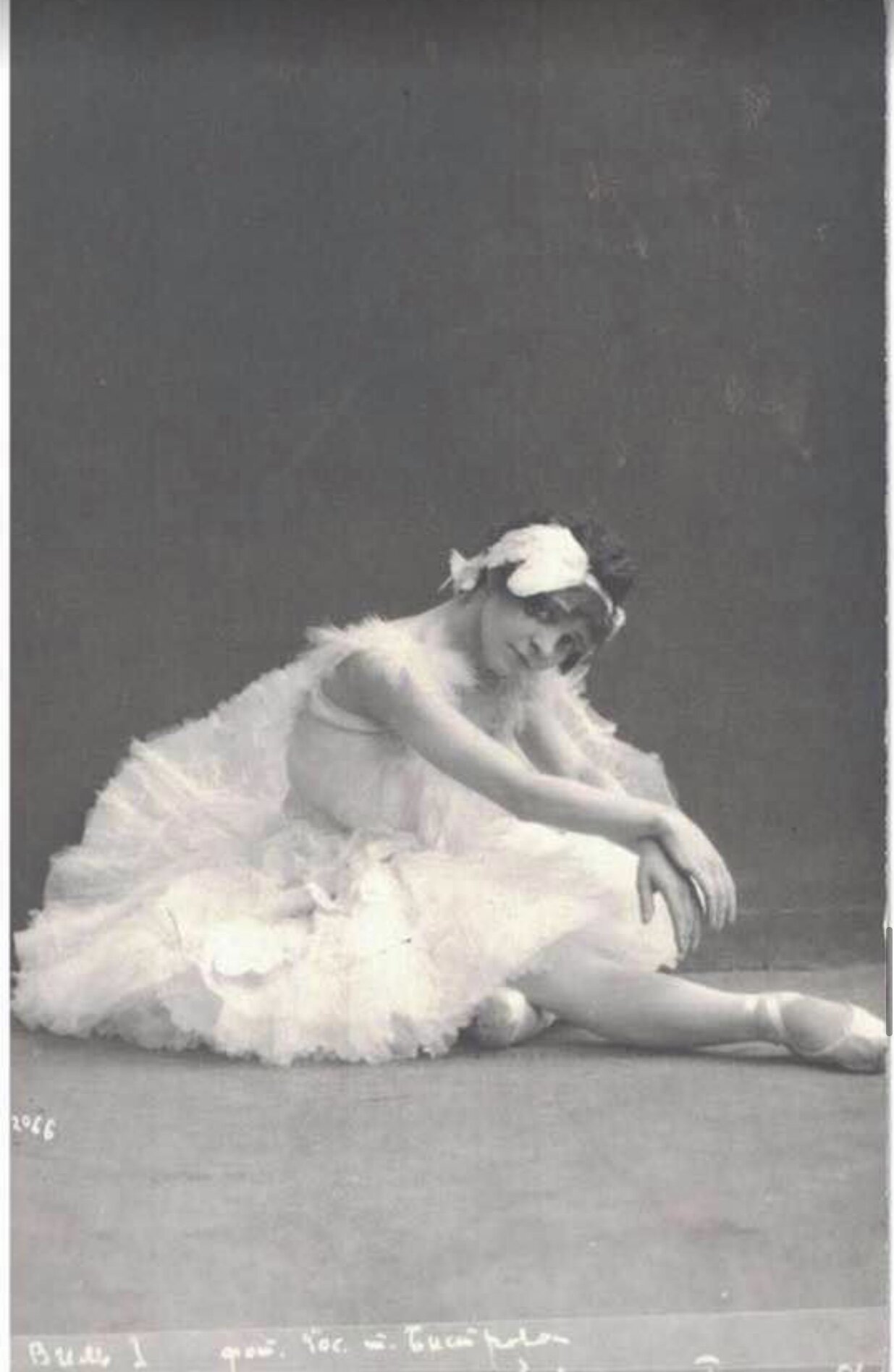

Photographs 143 (Margot Fonteyn in 1959), 144 (Tamara Karsavina 1908/1909), 145 (Lubov Egorova, 1913/1917), and 146 (Elsa Vill, 1918/1919) here show Odette alone at the adagio’s beginning - but with important divergences of position. Fonteyn’s position is akin to what we see in all modern performances of “Swan Lake”, Western or Russian. (My thanks for Andrew Foster and Sergey Belenky for helping with identifications and dates here.) So why is it not to be found among those who had worked with choreographers Lev Ivanov or Marius Petipa?

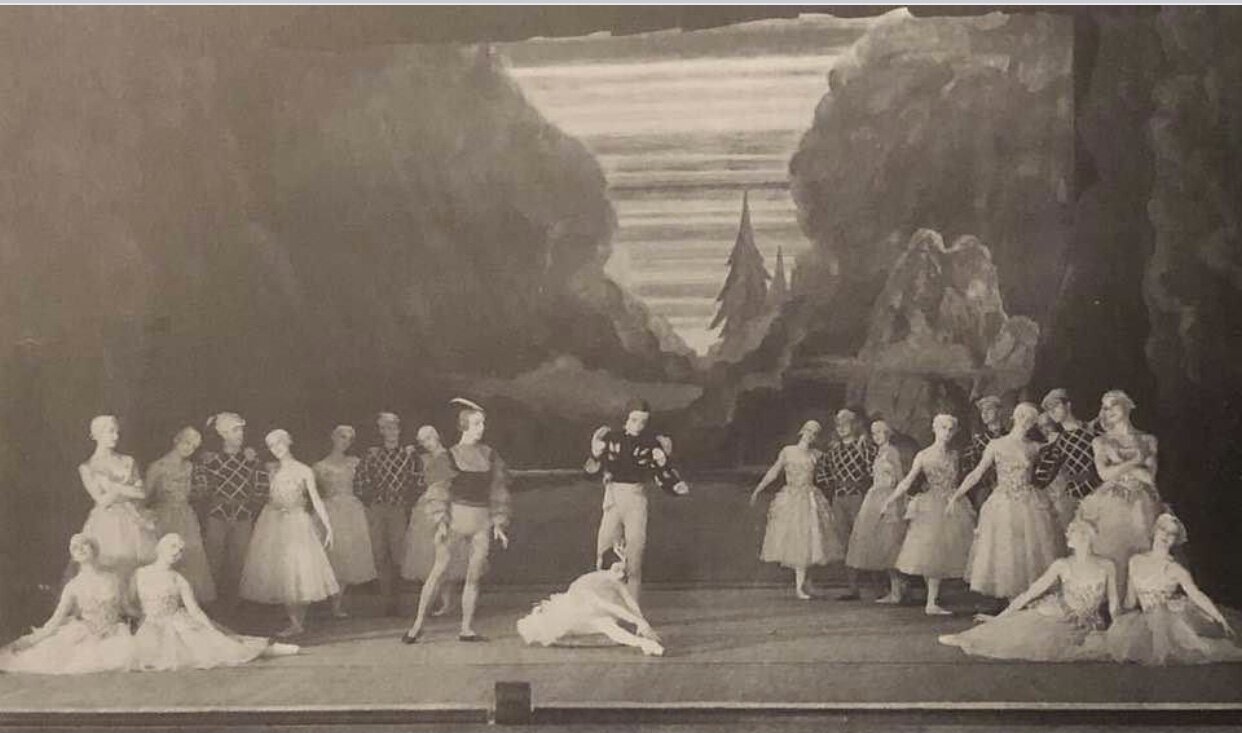

Photograph 147 (Alicia Markova, Robert Helpmann, William Chappell and the Vic-Wells Ballet in 1934) shows Odette in a posture close to the earlier Russian ballerinas seen in 145 and 146. Although the grouping has been arranged for camera, the production was staged by Nicholas Sergueyev, former régisseur to the Mariinsky.

Photographs 147, 148 (Fonteyn and Michael Somes on television in 1954), 149 and 150 (Viktoria Kapitonova, Alexander Jones, and Wai Chen in Alexei Ratmansky’s 2016 Zürich production), and 151-153 (Fonteyn, Somes, and Bryan Ashbridge with the Royal Ballet in 1959) all show Odette in context of Prince Siegfried, and in some cases others (Benno; the swan-maidens; the huntsmen) - but these contexts are quite different according to each production. The arc of eight swan-children in photos 149 and 150 comes from the Stepanov notation of Lev Ivanov’s original 1895 Mariinsky production: it seems that Sergueyev chose not to include them when he staged the 1934 production for the Vic-Wells, probably because St Petersburg “Swan Lake” tradition had already moved on before he left Russia. Fonteyn, who had made her debut as Odette in 1935 at age sixteen, usually danced the adagio without Benno when she was away from the Royal Ballet in the 1950s; in 1963, the Royal (like most other companies by then) edited Benno out of the adagio.

Photographs 152 and 153 show Siegfried assisting Odette (Somes and Fonteyn) to rise and prepare to dance her initial pirouette and arabesque.

Some of you will prefer “Swan Lake” without Benno or huntmen in this adagio, with the body language shown by Fonteyn in the 1950s photographs here, and/or without the backing arc of eight swan-children during the opening phrase here. That’s fine - as long as you’re aware that you’re preferring a post-Ivanov adaptation to the original choreography. You should at least go on to ask whether or not you’re seriously interested in the original choreography anyway; would you rather see a version that is continually revised to suit the dancers and tastes of each generation? Mathilde Kschessinskaya and Nicholas Legat were the first to perform the adagio without Benno, but their showier version did not become standard: Ivanov wanted the involvement of Benno, as did many Western productions (including George Balanchine’s one-act version, new in 1951) until the 1960s. (All dance-goers suffer from this problem: we all tend to harbour a lingering prejudice in favour of the version of choreography that first attracted us; few of us like to recognise that it contains anachronisms. I could include here the versions of Odette’s adagio featuring Galina Ulanova, Maria Tallchief, Maya Plisetskaya, and Natalia Makarova - but we would be wandering yet further from the source.)

I’ve deliberately omitted all photos showing Odette, while on the floor, lifting her face to gaze into Siegfried’s eyes. I well remember Markova coaching that moment in a televised 1980 masterclass: “Don’t look!”, she told the Odette there. She had first danced the adagio in 1925, coached by Kschessinskaya in the version for ballerina and a single partner; she made a puzzling film of this c.1932 with Frederick Ashton as Prince Siegfried. She then learnt the full-length role of Odette-Odile from Nicholas Sergueyev in 1934: her position in the 1934 photograph strongly suggests that Sergueyev taught her to avoid meeting Siegfried’s eyes at the opening of the adagio. Nonetheless many Odettes turn their faces to look him in the eyes as he assists her to rise. (In the 1954 TV film, Fonteyn does meet his eyes briefly, but this seems to have been an exception in her long history in the role.)

To me, if Odette begins the adagio with a direct look into Siegfried’s eyes, the whole drama becomes immediately sentimental. Much of the drama rests in her reluctance to meet his gaze. This opening is a quintessential image of his chivalry: he helps her to rise and to open up from this withdrawn position at his feet. Yet her eyes at first remain withdrawn from him: this adagio will develop the most remarkably psychosexual complexity in nineteenth-century ballet, as Odette vacillates between trust and independence. And yet they are not alone. The corps is present and responsive throughout: Ivanov’s plan was that the eight swan-children, Benno, and the huntsmen contributed too.

143 shows how Margot Fonteyn, at least in her prime, began the adagio in the fully folded-over position often known as the “dying swan” position, and with which all Odettes now begin the adagio. Fonteyn’s back struck all her colleagues as gorgeously supple and expressive (not least John Meehan, who partnered her in the Odette adagio - probably her final performances of it - when she was in her mid-fifties). Her back’s forward curve as Odette has struck many observers as ineffably swanlike; but the point of the ballet’s story is that Odette in this scene is not a swan but a woman. (Fonteyn herself, in perhaps her final piece of published writing, wrote in 1989 that she thought the swan aspect of Odette had become over-emphasised in recent years. It’s possible, though, that the same might have been said of her own Odette.)

At any rate, none of the pre-Fonteyn Odettes in this group is in that position. I would have assumed that they’re simply adopting modified position for their photographers: Karsavina’s and Elsa Vill’s support this. In June 2019, however, Alexei Ratmansky (while sharing those three photographs) proposed on Facebook that actually this position was how Odette really did begin the adagio. Above all, he observed, the Stepanov notation does not show the fully folded-over position: the Odettes of Lev Ivanov’s and Marius Petipa’s era neither fully straightened their extended upper leg(s) nor leant their torso(s) to touch their knee(s).

Since then, I’ve rediscovered photo 147 (Markova, Helpmann, Chappell). Again, this is certainly arranged for the camera - and yet Markova’s position as Odette is very specific, and remarkably close to 145 (Lubov Egorova) and 146 (Elsa Vill). This production was staged from the Stepanov notation by Nicholas Sergueyev; according to Ratmansky, Markova’s position is what the notation describes.

Fonteyn - the Odette of photographs 143, 148, 151, 152, and 153 - worshipped the Markova of 1934-1935 and surely did the same position when she danced her first Odette in 1935. Probably, when she adopted the more modern and stretched version of that position (perhaps from the mid-1940s on), she was by no means the first to do so: probably by then many Odettes, in Russia and the West, had turned it into the Pavlova/Fokine “Dying Swan” position.

Fonteyn, however, became singularly and globally influential, the exemplary prima of a young company (today’s Royal Ballet) that swept the West after the Second World War; I am among the many that tend to think that whatever Fonteyn did in the choreography by Petipa and Ivanov must have been more conscientiously close to the Mariinsky source material as she could make it. Well, she was one fastidious, beautiful, and stylish dancer; but her style had its neologisms.

Photographs 149 and 150 are screenshots of Ratmansky’s own 2016 Zürich production, with Kapitonova, Jones, and Wai Chen. They show that even Ratmansky originally went along with the neologisms. But in this and other ballet’s Ratmansky has been admirably open about re-checking the notation and the early photographs. He made the points about Odette’s initial position last year, after I had posted a photograph of Fonteyn’s Odette later in the adagio. The photograph, in which Fonteyn/Odette - supported on point from behind by David Blair’s Siegfried - leant forward was among the most widely admired I’ve ever posted; it showed the wonderful (and swanlike) plastique with which Odette, withdrawing from Siegfried even when supported by him, folded her torso over her own passé leg. Ratmansky, who didn’t deny its beauty, admitted that in 2016 he had given his Odettes the same body language. In 2019, however, he felt that neither the notation nor any other pre-1910 notation supported it as being Ivanov’s intention.

Do we know still nothing? Perhaps, just perhaps, we’re beginning to learn something.

Friday 28 August

143: Margot Fonteyn in the 1959 film of “Swan Lake” Act Two with the Royal Ballet.

144: Tamara Karsavina as Odette, Maryinsky Ballet, St Petersburg.

145: Lubov Egorova as Odette.

146: Elsa Vill as Odette.

147: Alicia Markova and Robert Helpmann, with swan maiden corps and huntsmen, 1934 Vic-Wells Baller first production of “Swan Lake” by Nicholas Sergueyev from the Stepanov notation.

148: Margot Fonteyn and Michael Somes in a 1954 TV film of the Odette-Siegfried scene.

149: Alexei Ratmansky’s 2016 Zürich Ballet production of “Swan Lake”, with Wei Chan (Benno), Viktoria Kapitonova (Odette), Alexander Jones (Siegfried).

150: Siegfried (Alexander Jones) prepares to reassure and touch Odette (Viktoria Kapitova), observed by Benno (Wai Chen) and framed by the eight student swan maidens. Zürich Ballet production by Alexei Ratmansky, 2016.

151: Odette (Margot Fonteyn) keeps her eyes averted as Siegfried (Michael Somes) begins to touch and partner her. Royal Ballet film c.1959.

152: In the same film, Odette rises to a kneeling position with Siegfried’s assistance, while keeping her eyes averted from his.

153: With Siegfried’s chivalrous assistance and yet without ever meeting his eyes, Odette has risen to point. She prepares to dance the adagio with him. Bryan Ashbridge (Benno), the corps and (yes) the huntsmen all stand by.