Anthony Dowell, poet of male adagio style

For the Prix Benois de la Danse

Anthony Dowell

by Alastair Macaulay

In June 2021, Anthony Dowell was given, in absentia, the Benois Prix de la Danse’s consolidated Leonide Massine prize at its week. I was honoured to be invited to write about him. In the event there was room to print only a minor fraction of my tribute in the Benois programme. Here is my complete essay.

In his dancing, Anthony Dowell exemplified Apollonian poetry, Romantic grace, effortless fluency, sculptural line. But let’s begin by speaking of his sheer technique: specifically of how his dancing transformed male adagio style. The word “adagio” is a musical term, used in ballet to characterise sequences of slow control that travel either not at all or gradually. Literally, it means “at ease”. (“Agio” is “ease” in Italian.) In 1964, when Dowell was twenty-one years old, the choreographer Frederick Ashton gave fresh “at ease” meaning to adagio with steps that he choreographed for Dowell as Oberon in The Dream (1964).

That ballet is a one-act distillation of Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream; Oberon is king of fairyland, a master of magic. In one slow legato phrase, with magic on his mind, Dowell-Oberon executed an advancing series of three double pirouettes on alternating legs, with each turn ending in arabesque penchée fondue. The mechanics of this sequence call for the utmost control and contrast. Each arabesque had photographic definition, and yet was merely a pause in the larger (turn-stop-turn-stop-turn-stop) phrase.

With Dowell – who danced Oberon over twenty-two years - this sequence had such fluency and clarity that few non-dance observers even knew it was difficult. Actually, it was unprecedented. In an arabesque, a dancer raises his (or her) leg directly behind him (or her). In penchée, the dancer raises his/her leg above hip height so that the dancer extends their line downward from the extended leg, through the torso, into the gesture of the front arm. Before Dowell, arabesque penchée almost entirely belonged to women. Although some Danish dancers (notably Erik Bruhn) and some Russian ones (notably Rudolf Nureyev) had already been opening up the possibilities of extended legwork and turnout in ballet adagio, the young Dowell’s dancing was a breakthrough. Since Dowell – many roles created for whom remain in international ballet repertory – arabesque penchée has been part of what men in ballet are expected to do.

Arabesque penchée is often recognized as the supreme test of line in ballet, the sense of a dancer’s physical continuity stretching from toe to hand and onward into the space behind and ahead of the dancer. Ashton, one of classical ballet’s supreme poets of line, had made many ballets between 1935 and 1958 for Margot Fonteyn, whom he felt incapable of making an ugly or unclassical shape. Now in Dowell he found a male dancer of comparable linear beauty, whose wide range of glorious arabesques made him, for many observers on both sides of the Atlantic, the ultimate epitome of line in the 1970s. Dowell’s mastery of line was amplified by his sense of gesture and the romantic eloquence of his eyes, which he used with skills evoking the dancers of South Asia.

Two and three centuries earlier, when ballet was young, adagio was the particular domain of the noble genre of dancers: tall, long-limbed virtuosi trained to exemplify the qualities associated with the ruling class, with kings and nobles. Much has changed in both society and ballet since then, but Dowell – tall, long-limbed, courteous, refined - immediately belonged as noble. Moreover, he was never just a soloist. During the 1960s, he inherited such noble roles as the male protagonists of Giselle, Swan Lake, and The Sleeping Beauty; he had forged a world-famous partnership with Antoinette Sibley, the original Titania of The Dream.

Yet Dowell was not just a dancer who matched the existing noble tradition - he took that tradition in new directions. The adagio sequences of The Dream, a ballet danced in many repertories around the world, still demonstrate this; so do those covering space rapidly in allegro tempo. Oberon circuited the stage in fast-turning sequences of steps (notably piqué and soutenu turns) previously associated with ballerinas. In Ashton’s A Month in the Country (1976), Dowell, dancing Beliaev, delivered an opening step of unprecedented intricacy, technically trickier than those Dream pirouettes into penchée: from executing a triple pirouette on one leg (in attitude back), he advanced his raised foot and stepped into piquée arabesque penchée on it. (Over forty years later, there are still few male dancers in the world who can manage that.) What’s more, that penchée’s line was unorthodox, with the arms and chest creating a diagonal line steeper than that of the leg. (See photograph 1.) This surprising line, compounded by the frank openness of the chest, immediately epitomized the alien quality that Beliaev, the twenty-year-old tutor, has in the aristocratic household.

Dowell never danced on point, but his way of stepping onto demi-point – often in piquée arabesque - became one of his signatures. Today it’s still recognized as that by the many male dancers who inherit the roles created for him. With Dowell, this use of demi-point was combined with a richly textured use of plié. To watch him sustain the line of an arabesque while seamlessly lowering his heel and then bending his knee was a luxury for those who watched him; thanks to the wealth of “Dowell” roles still danced around the world, it has become part of dance masculinity.

In his partnerships with Sibley and many other ballerinas, Dowell showed how a male dancer can be a ballerina’s kindred spirit, her poet, her lover. Here, too, he extended the possibilities of the male dancer’s art. In Month, he was also given sustained pas de deux with three dissimilar women. When partnering Vera, the teenage ingénue of the household, Dowell/Beliaev slowly lifted her off the floor - while he himself gradually turned twice - until he held her high above his head. This was a new kind of partnering virtuosity, and yet, again, few noticed it was hard: the theatrical effect was simply to show Vera’s escalating rapture.

The 1960s were a decade when women and men, in society and dance, extended the boundaries of what each gender might be and do. The term “unisex,” much used in 1960s fashion, might have been applied to sections of such choreography as Ashton’s Monotones (1965-1966 –Dowell created one of the roles) and Nureyev’s The Nutcracker (1967, in which Dowell soon danced the central role Nureyev had made for himself), in all of which men and women sometimes executed the same highly controlled steps side by side. Again, Ashton had already anticipated this in The Dream. During the pas de deux for Titania and Oberon, Sibley and Dowell performed arabesque penchée together (see photograph 2), like mirror images meeting to joining their arms in a single diamond shape. (In New York, Sibley and Dowell were nicknamed “the Heavenly Twins.”)

In the larger world of the 1960s and 1970s, women were starting to claim and win new rights in society (“Women’s Lib” was the term widely used). In ballet, largely dominated by women dancers since the 1930s, men were claiming new eminence. During the 1960s, Rudolf Nureyev (five years older than Dowell) and Erik Bruhn (fifteen years older) both added new adagio solos to the role of Siegfried in various productions of Swan Lake. (See photographs 2 and in 1968, Ashton created, for Dowell, not only an adagio solo for the prince in The Sleeping Beauty but a new Awakening pas de deux too, in which the hero both had a virtuoso solo and elsewhere danced with the same flowing arabesques as Sibley, his Aurora. Ballet was changing; observers wryly referred to this transformation as “Princes’ Lib”. Margot Fonteyn, looking back in 1979 on this transformation, wrote “The era of the ballerina is over.” She meant not there were to be no future ballerinas but that the ballerina henceforth would now have to share the limelight.

While Nureyev, with his phenomenally exciting bravura dancing, raised the bar for all male dancers, Dowell did the same. And the two men raised the bar for each other. Almost immediately, Nureyev danced the Sleeping Beauty production with the dances that Ashton had created for Dowell, while Nureyev – though not until the 1970s - also began to dance Oberon in The Dream.

The lyrical refinement of Dowell’s classical style, his personal beauty, the innocent calm of his stage persona, the cantilena fluency of his phrasing, and the intelligent eloquence of his acting were all factors that lured other choreographers to create roles for him. He was Benvolio in the premiere of Kenneth MacMillan’s Romeo and Juliet (1965); he and Sibley were the youngest of that production’s first four star couples as the title lovers. (Later, he would also dance Mercutio.) MacMillan once said that “All the superlatives” should be applied to Dowell; those three words became the title of a television documentary on Dowell. MacMillan went on creating many further roles for him until 1991 – notably the Chevalier des Grieux in the three-act Manon (1974). (There was another Dowell role that Nureyev also danced.) Over the next 14 years, Dowell performed the role with increasing emotional power, showing in solo sequences how des Grieux travels from shining innocence to moral conflict to abject torment. (He also often danced the role of Manon’s attractively sinister brother Lescaut, giving the role a further element of dark slyness.) In 1991, when MacMillan adapted Chekhov’s play The Three Sisters as the one-act ballet Winter Dreams, Dowell – now in his late forties - created the role of Kulygin, the cuckolded husband of Masha: while the romantic Masha falls in love with Vershinin, the unromantic Kulygin is far from unfeeling. MacMillan gave Dowell a solo of tragic-comic pathos that showed how far Dowell’s theatrical skill had evolved over the decades; Dowell went on performing it into his sixties.

In 1967, Antony Tudor made Dowell the protagonist – “The Boy with Matted Hair” – in his narrative one-act ballet Shadowplay, a ballet based on Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book and still danced this century: the role had great impact on awakening Dowell’s instincts as an interpreter. In 1974, Hans van Manen made Dowell the central figure of his pure-dance Four Schumann Pieces, which memorably showcased a wide range of Dowell’s adagio and allegro skills. That was yet another Dowell role that Nureyev would also dance; and in 1982 Nureyev cast Dowell as Prospero in the premiere of The Tempest, his one-act adaptation of Shakespeare’s play.

The many ballerinas whom Dowell partnered other than Sibley included Lesley Collier, Fonteyn, Cynthia Harvey, Gelsey Kirkland, Natalia Makarova, Merle Park, Jennifer Penney, and Lynn Seymour. In 1977-1978, he spent a year in the United States as a principal of American Ballet Theatre, a company to which he later returned, not least as the original Solor of Makarova’s three-act production of La Bayadère (1980).

In his mid-forties, while still dancing lead roles, he became director of the Royal Ballet, a post he held for fifteen years. Those years contained many unforeseen difficulties for the company - not least the deaths of Ashton (1988) and MacMillan (1992) and the two-year closure (1997-1999) of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, for extensive rebuilding – but Dowell steered the company into an era where far more of its principal dancers were international. The “British” styles of Ashton and MacMillan choreography became ones he opened up to such dancers as Carlos Acosta, Nina Ananiashvili, Altynai Asylmuratova, Alina Cojocaru, Sylvie Guillem, Laurent Hilaire, John Kobborg, Irek Mukhamedov, and Tamara Rojo. A skilled coach himself and a friend to many dancers of his own generation, he passed on the tradition to many younger dancers, ensuring the future of both his company and its choreographic legacies.

Since his retirement from running the company, Dowell has often returned, both to perform and to coach; he has also worked as coach internationally. Ashton, in his will, bequeathed both The Dream and A Month in the Countryto him: and so Dowell in this century has coached such dancers as Roberto Bolle, Federico Bonelli, David Hallberg, Julie Kent, Evan McKie, Vadim Muntagirov, Gillian Murphy, Marianela Nuñez, Natalia Osipova, and Zenaida Yanovsky. His dancing had epitomised one kind of line. His continuing work with younger dancers now represents a different sense of line: passing the inheritance on to those who never saw him dance.

@Alastair Macaulay 2021.v.21

1: Anthony Dowell’s piquée penchée arabesque in Beliaev’s opening solo in Frederick Ashton’s “A Month in the Country” (1976). Beliaev takes this piquée penchée as his petit développé conclusion of his opening triple pirouette en attitude. Dowell, apparently incapable of an ugly or unclassical shape, made the unorthodox line here the perfect epitome of Beliaev’s fresh but alien presence in the aristocratic household Photo: Leslie E. Spart.

2: Anthony Dowell and Antoinette Sibley (“the Heavenly Twins”) as Oberon and Titania in Frederick Ashton’s “The Dream” (1964). They continued to dance this ballet until 1986. Ashton left it and “A Month in the Country” to Dowell, who has now supervised stagings of it in countries across the world.

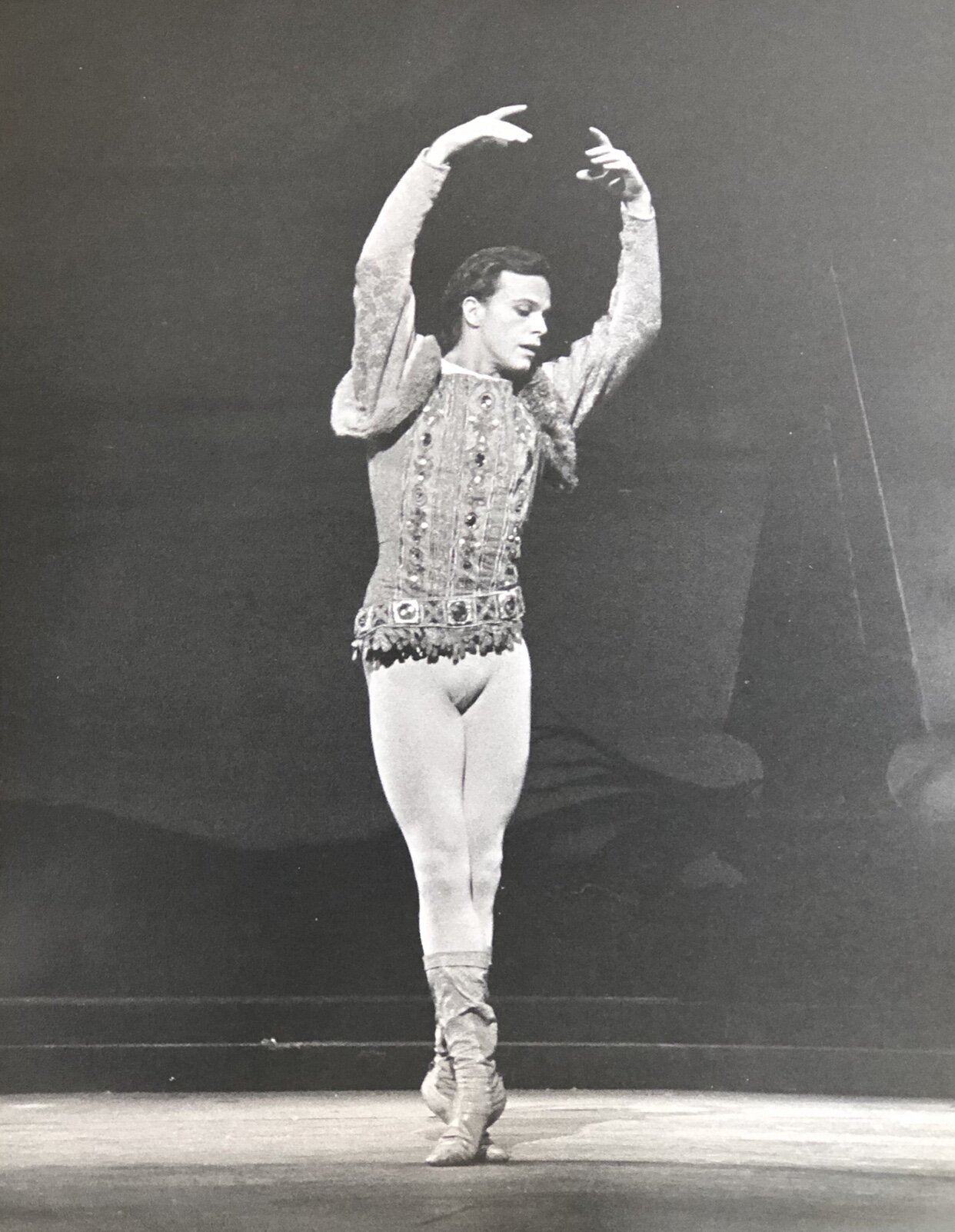

3: Anthony Dowell in Rudolf Nureyev’s 1963 adagio Act One solo for Prince Siegfried in the Royal Ballet production of “Swan Lake”. (It is fair to assume that Frederick Ashton advised Nureyev in the choreography of this variation; it is also unlikely that Nureyev ever danced it as beautifully as did Dowell.) This photograph, by Leslie E.Spatt, was probably taken in the early 1970s; it shows the “Swan Lake” designs by Leslie Hurry.

4: Dowell in the same Nureyev solo for Prince Siegfried - see 3. Photo: Leslie E. Spatt.

5: Dowell in the same Nureyev solo for Prince Siegfried - see 3. Photo: Leslie E. Spatt.

6: Dowell in the same Nureyev solo for Prince Siegfried - see 3. Photo: Leslie E. Spatt.

7: Dowell in the same Nureyev solo for Prince Siegfried - see 3. Photo: Leslie E. Spatt.

8: Anthony Dowell, dancing Frederick Ashton’s Sarabande Act Two solo for the Prince in “The Sleeping Beauty”. Ashton had choreographed this for Dowell in 1968; this photograph by Leslie E. Spatt shows Dowell dancing it in Ninette de Valois’s new 1977 production. Dowell stopped dancing the role after 1978; this Ashton solo remains part of the current Royal Ballet production and the Boston Ballet production too.

9: Anthony Dowell, dancing Frederick Ashton’s Act Two Sarabande solo in the 1978-1972 Peter Wright production for which it was originally choreographed. Photo: Leslie E.Spatt.

10: Anthony Dowell, dancing the Prince’s Act Three variation in “The Sleeping Beauty”. This photo shows Dowell dancing at the dress rehearsal of Ninette de Valois’s 1977-1992 production. He had been absent with a neck injury for almost twelve month; this photograph demonstrates the beauty of form with which he returned to the stage. Today, Royal and other interpreters of this variation tend to take this piquée first arabesque (in the variation’s opening zigzag) with head turning to face the audience (or the mirror); but it was characteristic of Dowell to emphasise the arabesque’s line with his face abs eyes.

11: Anthony Dowell as Solor in Rudolf Nureyev’s 1963-1987 production of the Realm of the Shades from Marius Petipa’s “La Bayadère”. Photo: Leslie E.. Spatt.