“Oleanna” revisited; ourselves revisited

Oleanna, an eighty-minute “two-hander” by David Mamet new in 1992, is - famously - about the power struggle between a male university professor and a female student. By the end, he is ruined in one sense; she in another.

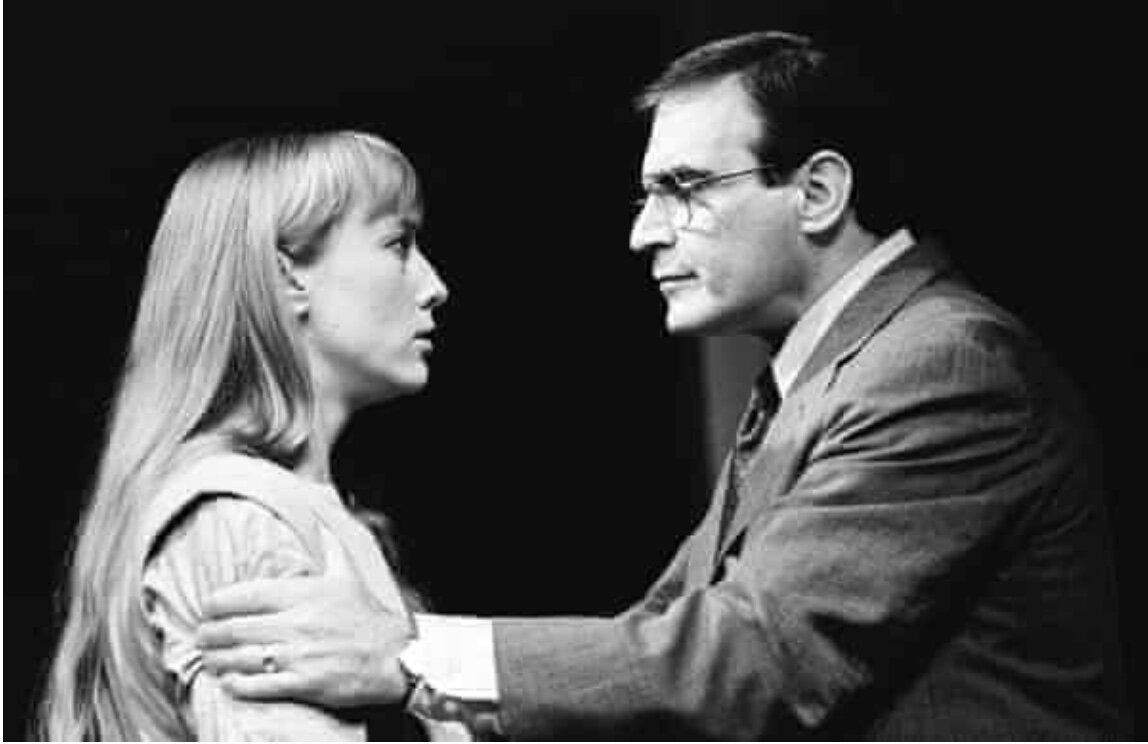

When the play was young in America, it was widely said to be prompted by the Anita Hill/Clarence Thomas hearings. It was always, however, a good enough play to open up much more. When it had its London premiere at the Royal Court Theatre in 1993, directed by Harold Pinter, it was widely said to divide its audiences, making men side with the male professor, women with the student; the same gender-divided reaction had occurred in New York. Curiously, I saw that production with a former student of mine, a woman who had gone on to become a successful newspaper dance critic. Sure enough, she sided with the student (Lia Williams) and I with the professor (David Suchet); I recall that we (good friends to this day) stared at each other in stupefaction to find each other was entertaining the opposite opinion - and to find that men and women in every audience were doing the same, almost entirely along gender lines. (For the London original, Pinter used the ending that Mamet had given to the out-of-town world premiere. Mamet and he clashed, since Mamet insisted that his revised ending was the only one that should be used. In the long run, Mamet won: it’s apparently nearly impossible even to find a copy of the first version.)

Tonight, when I watched it with an actress friend (it’s running at the Arts Theatre until mid-October), our reactions proved to have grown far more various, more multifaceted: it seems now to have long anticipated the Woke politics of today, and my sympathies swung considerably during each of the three scenes. I heard afterwards that when this current cast - Jonathan Slinger, Rosie Sheehy, directed by Lucy Bailey - played it in Cambridge, students afterwards remarked that nothing has changed and that it could have been written about supervisions they had had that week. (I’m amazed by this. It was nothing like the Cambridge supervisions I had in the mid-1970s, but I was a male student, and one of my teachers, who remains a friend, was female, while my main Literature supervisor was simply dull and frivolous. When I taught B.A. students between 1980 and 2002, chiefly in 1980-1988, I was mainly highly conscientious, but the play now raises the memories of one isolated incident c.1985 when I was too harsh to one (in my view) amiable but lazy student. She complained; I apologised; and we were both fortunate to have an excellent director of the B.A. course who advised us both. Still, I don’t forget, and I do still castigate myself for every time (few, I hope) when I was, even forty years ago, insensitive to a student; and I’m grateful that many of my students, like the one with whom I watched the 1993 Oleanna, have remained friends.

My 1986 experience was minor compared to the one in Oleanna. Yet I, like every man in academe and related areas, have had to go on learning that men can too easily sound - and be - overbearing, bullying, insensitive, privileged, patriarchal. My hunch is that many in today’s audience, male and female, now feel the same, but also feel that Mamet’s female student is by no means entirely sympathetic. As so often in my life, I wish I could revisit my original experience of the play, in which David Suchet and Lia Williams were both brilliant; but I’m most curious to revisit my own 1993 self. Bring on that time machine!

More important yet, though, is to investigate our own reactions now: Oleanna itself seems more prescient and yet subtler, more ambiguous, and unusual than it did. We ourselves have changed more than the play; we can’t help being shocked by that change, which we often project onto both play and production. To what extent is any of us woke, to what extent complacent?

Many of Mamet’s plays are about gender politics. I remember that, in 1994, after the London production of The Cryptogram, my male companion remarked “I’d forgotten what a misogynist Mamet was.” Since I had followed the play largely from the heroine’s point of view, I was appalled by this reaction: an intense argument - about ethics and gender rather than the play - followed for two hours, and perhaps for years. What other current playwright had had the same effect, making audiences argue not just about what happened onstage but about its implications in the world?

Mamet is also a classical author in that the meanings of the play lie within the precision of his writing. In this sense, he is part of the same modernist movement in drama as Pinter, to whom he dedicated Glengarry Glen Ross (1983). The rhythms of Oleanna - and so many other Mamet plays - are dazzlingly precise: they chart details of the power play between the two characters even more revealingly than the actual words.

One of the many great mysteries of the twenty-first century is that Pinter and Mamet, stylistically akin, turned to politically opposite sides. In his final years, Pinter gave up playwriting for concentrate on poetry and politics; when he won the Nobel Prize in 2005 for his plays, he devoted most of his acceptance speech to a denunciation of American foreign policy. Mamet, in 2008, the year of Pinter’s death, published an essay “Why I Am No Longer a Brain-Dead Liberal”, explaining his gradual rejection of political correctness and move to conservatism. Liberals, not least for that reason, take delight in finding Mamet’s recent plays poor. I’m liberal, but I don’t enjoy any deterioration in Mamet: the world is large enough to include a brilliant right-wing artist. He’s in his mid-seventies: does his greatness all belong to his liberal past?

Friday 27 August

1. The set for the Arts Theatre Oleanna while the audience is still arriving. The designs are by Alex Eales; lighting by Oliver Fenwick.

2: Main publicity poster for the 2021 Oleanna.

3: Lia Williams and David Suchet in Harold Pinter’s 1993 Royal Court production of the British premiere of Oleanna. Photo: Tristram Kenton, Guardian.

4: Lia Williams and David Suchet in Harold Pinter’s 1993 Royal Court production of the British premiere of Oleanna. Photo: Tristram Kenton, Guardian.

5: Jonathan Slinger and Rosie Sheahy in Lucy Bailey’s 2021 production of Oleanna, at the Arts Theatre till October 23. Photo: Nobby Clark.

6: Rosie Sheahy and Jonathan Slinger in Lucy Bailey’s 2021 production of Oleanna, at the Arts Theatre till October 23. Photo: Nobby Clark.

7: Jonathan Slinger and Rosie Sheahy in Lucy Bailey’s 2021 production of Oleanna, at the Arts Theatre till October 23. Photo: Nobby Clark.

8: Jonathan Slinger and Rosie Sheahy in Lucy Bailey’s 2021 production of Oleanna, at the Arts Theatre till October 23. Photo: Nobby Clark.

9: Lia Williams and David Suchet in Harold Pinter’s 1993 Royal Court production of the British premiere of David Mamet’s Oleanna.