Young Choreographer meets Old Critic - Gavin McCaig, 27, and Alastair Macaulay, 67, interview each other

Gavin McCaig’s new creation for Elmhurst Ballet School will have its premiere in Birmingham on July 7, 2023. AM.

AM. We hadn’t met when we began this email conversation in March, but we’d known each other for years. You and I both used to write for the British monthly “Dancing Times”; and we’ve been following each other on Instagram. When I moved back to the U.K. in 2019, you were one of the people I most wanted to meet. You’ll ask me questions as we go along, but I’ll start.

Gavin, how long have you been a dancer with Northern Ballet? Where are you from? How did dance happen for you? What was your training and experience before Northern?

GM. I’ve been dancing with the company for eight seasons now. How fast time has passed. I’ve blinked and I’m one of the “older ones”. I’m originally from Motherwell in Scotland, a national heritage I’m very proud of.

AM. We’re probably cousins! My father’s parents and their ancestors came from East Kilbride, some twenty minutes’ drive west from Motherwell.

GM. I can’t believe that! I have spent many a weekend in East Kilbride, not far at all from my family home.

Dance happened for me long before it was formalised through training. Dance was everywhere - and anywhere - music came on: most notably at the mini-dancing competitions my dad would hold for my sister and I in the lounge. It was my Aunty Shirley, an ex-dancer, who took me to my first dance class. As one might guess, I felt right at home. It was such an outlet for me and a chance to be myself.

AM. All this is like fiction to me, because I haven’t seen you dance. But it’s a story I enjoy and believe. You also choreograph. When did you begin to make dances? What have you made?

GM. I started to dance very young.… In my head, or on myself in my bedroom, without any space and without any inhibition. Usually I’d create the movement to lyrical pop music. At that age, with so little understanding of the form, it’s not about how it looks: it’s about how it feels.

Once dance classes became a regular activity for me, we’d have the opportunity to make a festive dance around Christmas time and present it with my all-female class. I loved the scope of possibility in the task of making dance, even at that young age.

Then later came the more formal entries for choreographic competitions in vocational school and suchlike. Choreographic assessments at ENB School presented a structured creative outlet, leading to my study of Dance on Screen for my dissertation. I choreographed a dance for three ladies called “Figure: 3” and made a dance film shot at Rambert’s studios as part of my assignment. I think that was when I realised: “Wow, it’s really cool to create!”

Then came a professional career and opportunities with the company.

AM: Let me pause you there. Your dance training was in both Glasgow (the Dance School of Scotland) and London (three years at English National Ballet School). Are there points you’d like to make about what you did or didn’t learn in all those years of training ? Other than ballet, what did you study?

GM. I was so lucky during my training; I talk about my gratitude to where I trained regularly. Both schools are centres of excellence and shaped so much of who I am today. At The Dance School of Scotland, I joined like-minded young people from across Scotland and formally began training in classical dance under Kerry Livingstone, Eleanor Tyres and Elaine Holland. Four years went by quickly alongside academic studies. At sixteen, I successfully gained a place at ENBS. I feel I was at ENB School during a bit of a golden era! We had a wonderful team - Anu Giri, Delia Barker as co-Directors, Samira Saidi as a Head of Dance. Alongside this, a superb dance faculty - truly top-notch tutors like Paul Lewis, Ivan Dinev, Nathalia Barbra, Larissa Bamber, Chris Wright, and Sarah McIlroy, who all gave us everything and forged our approach to technique beside our attitude and appreciation of the wider art form. I went through some rough times at ENBS, mainly on account of continuous exposure to injuries and the inevitable emotional fallout of being unable to dance. I had only been at ENBS for a few months and was on an operating table getting an hip arthroscopy. These experiences shape us though, thicken our skin and prepare us for the big, complex world of adulthood.

AM. Your CV tells us that, as a graduate student, you toured for a year with Scottish Ballet, in Christopher Hampson’s “Hansel and Gretel”. Tell me more.

GM. During my graduate year, Scottish Ballet needed an extra boy or two to fill some spots in their festive production, so I was given the opportunity to head back up to my homeland and perform with them. It was a real insight into how company life works and I’m lucky to have had that kind of chance. A full contract never followed for me there, though.

AM. So was Northern Ballet your first proper dance job?

GM. Indeed, an apprenticeship offer from David Nixon allowed me to leave school with the security of a salary and the promise of performing a repertoire which really appealed to me. I had watched the company perform throughout my time at school in productions like “A Christmas Carol”, “The Great Gatsby” (which I have now danced many times), and “A Midsummer Nights Dream”.

AM. How aware of you of Northern Ballet’s history and/or traditions? I’m very old, so I used to know Laverne Meyer, who founded it in 1969 and ran it till 1976. (I knew him in the 1980s.)The company website tells us of the successive artistic directorships of Robert de Warren (1976-1987), Christopher Gable (1987-1998), Stefano Gianetti (1999-2000), David Nixon (2001-2022). Your current artistic director is Federico Bonelli, whom many of us remember as a leading dancer at Covent Garden from 2004 until he moved to Northern in 2022. Yet I’ve seen remarkably little of the company, I blush to say.

You’ve been a Nixon dancer: are you conscious of pre-Nixon traditions at Northern? In particular, Gable stamped the company as a vehicle for narrative dance drama, with certain acting methods unusual to the ballet world. How much is Gable’s name still spoken?

GM. I am not aware of the Meyer era at all really, other than what I have read about in the literature of the company's history.

I’d definitely describe myself as a Nixon dancer; I do believe he both continued the Gable legacy of narrative dance within the company and moved it forward. David and his wife Yoko are passionate advocates of developing young dancers and giving them the tools needed to flourish within the company’s repertoire whilst looking after their bodies in the process. I have immense respect for what David achieved during his time at the company: before he left, I summed it up in a piece for “Dancing Times”. I need to mention the ingenuity of some of his shows: “A Midsummer Night's Dream” in particular but also the modern interpretation of “Beauty and The Beast”, which returns to the repertoire this autumn. I’m so grateful to have worked with him and Yoko for the bulk of my career. They are truly talented, special people.

AM. These are early days for Bonelli. Can you spot signs of change as yet?

GM. Certainly. I think for me it’s about embracing a new style of leadership which is very different to David’s. There are nods towards more classical work coming soon and perhaps different approaches - different from what many of us have been used to. Change is good. There’s always value to be found in fresh perspectives being brought to the fore.

AM. What are the roles from which you’ve learnt most - and why?

GM. At the moment, I’m dancing Tom in “The Great Gatsby” - which is a privilege. Fitzgerald is one of my favourite authors and the ballet is arguably one of David’s best works for the company. Starting as one of the butlers during my apprenticeship year and now dancing a principal role is quite special. Other roles I’ve cherished include Acololyte in Jean-Christophe Maillot’s “Romeo and Juliet” and John Brown in Cathy Marston’s “Victoria”, in which I got to wear a kilt and felt most at home. There is also Athos in “The Three Musketeers” and St John in Cathy Marston’s “Jane Eyre”. The roles have been rewarding, however, so much of the work I have done in the ensemble has also brought me real joy. Dancing Kenneth MacMillan’s “Gloria” at the Royal Opera House was a once in a lifetime opportunity. And the many hundreds of shows I have done, over the years, in the corps, through David’s work, have taught me about discipline, resolve and collaboration with my colleagues. The experience you gain from working in an ensemble is invaluable.

My turn to ask questions. I’ve read many of your articles over the last 10 years, not just in “Dancing Times”. I always followed your pieces for the “New York Times” with interest - and thoroughly enjoy your to-the-point prose. How did you start writing?

AM. When I was sixteen, my best friend at school insisted that he and I must write letters to each other during the holidays, and then after leaving school. We probably wrote two letters each per week, probably all of them covering six sides (large handwriting, mind you). They had to be entertaining, and they certainly could include any theatrical or musical performances we’d seen.

By the time I arrived at university at eighteen, I was a passionate, prolific, and instinctive letter-writer. (I still am, as friends and family will testify.) I was wild about opera, so I wrote long letters about that to a range of friends. But I suspect I was trying to write letters to connoisseurs (I had several highly musical friends at university), letters that tried to make me sound like another connoisseur: probably mega-dull!

I began to watch dance at age eighteen, gradually building enthusiasm over the next two years. Then at age twenty I saw Margot Fonteyn (“Romeo and Juliet”) and Lynn Seymour (“A Month in the Country”). Those two experiences made me an obsessive dance-goer; I also saw lots of Rudolf Nureyev, Anthony Dowell, David Wall. Well, I needed to write letters about all that!

The first dance letter I wrote to my friend Bridget - she read Classics with me at the same college but had studied ballet and loved watching it on TV - made her say “I loved your letter, I read it aloud to my mother, and we both think you should become a dance critic.” I didn’t take them seriously - I knew I knew a lot less about ballet than I did about opera, and the idea of being dance criticism sounded silly to me anyway - but I did feel licensed to go on writing letters about dance to Bridget and other friends. When I was twenty-one, I moved to London, working in bookshops, and began watching four or more dance performances a week. Nobody would believe now how much time and space I spent writing letters! I desperately needed to reconcile what I knew I’d seen with what I knew I’d felt. Bridget and others kept on being encouraging.

Finally, when I was twenty-two, the right London friend took me aside to urge me to commit to the performing arts in some way. This time, I paid attention, though I didn’t know whether I should try to get into arts administration or criticism or what. I was reading almost all the dance critics - I’d already been reading multiple music critics since I was eighteen - not because I thought I could do it too but because most of them knew so much; I wanted to learn, learn, learn. And I read collections of reviews of performances I’d never seen, above all those by Edwin Denby.

Then I got a break. A friend, Sarah Montague, who wrote a dance column for a monthly magazine named “Ritz” had to remain in New York for visa reasons. She handed over her column to me, with five days’ notice to deliver my first piece. Only when I read it in print did I realise how gratifying that would feel.

GM: A hand of fate - I love it!

AM. But writing is a form of performance. Good writing - including good criticism - is a form of self-revelation. For me, it therefore usually involves something like stage fright, not just when I’m writing but while I’m waiting to see the impact each piece will make on readers.

Sometimes there’s a big difference in the piece you thought you wrote and the piece as others read it. People see jokes or sarcasm you never intended as such, or they don’t notice the point that you felt was most important or best written. Sometimes that’s your fault; sometimes it’s theirs.

I’d like many of the pieces I wrote in my first ten years to be destroyed! At the time, though, I was a man with a mission. And it was important to “Ritz” that its writers were entertaining. So I made jokes, I dropped names, I gossiped.

But I also began working on describing and analysing dance, in ways that would hold my readers’ attention. That’s the task that never stops. Forty-five years on, I can say it never gets any easier. The rare occasions on which I feel I’ve succeeded to a fair degree really are deeply fulfilling.

Dance is a particularly hard art to describe - i’ve written many reviews of theatre and classical music - yet, inevitably, I go on seeking out the aspects that are hardest. When I began at the “New York Times”, and realised how much space I had, I deliberately set about trying to analyse how choreography responds to music. That’s the hardest of all, but it’s also often the most intimate part of the dance experience.

When I stepped down from the “New York Times” in 2018, forty years after I’d become a critic for “Ritz”, I had a letter from a reader in Massachusetts. He wasn’t terribly interested in dance; he was a music person who read the music critics, but I was the one dance critic for whom he made an exception, just for my writing. That was a big compliment, but what touched and surprised me was that he said I reminded him of the English music critics he had once read in the British music magazines decades before. Well, of course those were really the first critics I’d ever read, long before dance caught my fancy. Here’s hoping that all those hours in my late teens of poring over record reviews by Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Philip Hope Wallace, Andrew Porter paid off!

I mentioned my friend Bridget (Buckley). She and I were Classics students at the same college with Richard Fairman, who was also a very skilled pianist. Really, I learnt more about music from Richard in my three years at university than I did about Classics: not about making music but about listening to it. Well, Richard became a music critic at the same time I became a dance critic. Ten years later, when he had been at the “Financial Times” for three years, he said the word that led to the “FT” inviting me to review for it. He and I and Bridget are still friends - her two daughters are both professionals in different areas of classical music - and he’s been the “FT”’s chief music critic for maybe ten years. In 2022 and now 2023, he’s brought me back to the “FT” as a guest music critic: a real honour and pleasure for me.

Another old colleague who became a writer at the same time as me is the British dance academic Stephanie Jordan. Both of us began as all-rounders who covered everything from ballet to postmodern dance; and both of us taught dance subjects at B.A. and M.A. level. But, after maybe twenty years, she, as an academic, began the discipline of analysing choreographic musicality. All dance connoisseurs should read her book “Moving Music” (Dance Books, 2000), which says so much about the different ways in which twentieth-century ballet choreographers have responded to music. I’m quoted in it a few times: it was a real thrill to discover that she and I had been thinking along parallel lines.

What about you? I didn’t grow up with dance; you did. But have you always written about dance? What kinds of dance writing have you done so far?

GM. I have written about dance since my vocational training started. Perhaps it was a way of processing the intricacies of it or documenting my experiences in a way I could reflect on. Via my work in the “Dancing Times”, I realised it could give me the opportunity to open up conversations and explore talking points for myself as a young artist in the industry. These days, everyone is scared to have an opinion, which is why it’s key we uphold the importance of dance writing and criticism, embracing the subjectivity of our art form and the varied views on it all.

AM. Hurrah! You’re a kindred spirit.

GM. The conversations around work and progress for ballet can only happen when everyone can contribute, discuss and reflect - regardless of age, creed, culture or experience. Magazines like the late “Dancing Times” facilitated these conversations…. I am hopeful, however, they’ll continue in other mediums and other ways.

AM. What are you reading right now?

GM. I am at the moment re-reading “Devotions”, which is a collection of Mary Oliver’s best poetry. During creation, poetry is such an inspiration and buffer for me

AM. I ask because I’d advise every writer to be a constant reader. I knew one critic who came to avoid reading as much as possible, of any kind. I can only say it showed in his prose.

I’m impressed that you’re reading poetry. One old friend of mine in the theatre arts told me he never reads poetry. Again, it occurred to me that it showed in his work: it’s prosaic in admirable ways but without those leaps of the mind that often characterise poetry. Théophile Gautier and Edwin Denby, important dance critics both, were both published poets; Mindy Aloff and Jack Anderson - today - are others; so was James Monahan, an important British critic for more than thirty years after the Second World War. Joan Acocella, Arlene Croce, Mary Clarke, Claudia Roth Pierpont are other dance writers who’ve quoted poetry in their dance writing. Frederick Ashton, George Balanchine, Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, Paul Taylor are among the choreographers who draw from published poetry. When Ashton first saw Cunningham’s work in 1964, he said to Cunningham “You are a poet - and I like dance to be poetic.”

GM. I love that Ashton quote. Dance is poetry in motion! I feel strongly that the concept of proposing an image to the audience onstage is much like the one of proposing one to a reader in a poem. The best dance feels like poetry to me.

Has writing itself always come naturally to you?

AM. Well, I work very hard at it! Arlene Croce once said “I don’t write, I rewrite”: well, that’s true for me too. Sometimes I work all day on a single paragraph. Then I look at it the next morning and completely rewrite it again. Arlene once read me the opening paragraph of a piece she was working on; then she told me she’d worked on it for six weeks.

GM. Much like when I remake a sequence of steps or reimagine a scene in a ballet… the process of refining and reflecting is an important one indeed.

AM. I’d add that, if you really work and work on some prose, then some other prose sometimes can materialise remarkably fast. Here’s a peculiar example that still surprises me.

On the day that the news of Michael Jackson’s death broke in 2009, a Friday, I was working on a review of Mark Morris’s “Dido and Aeneas”, which I’d seen in Connecticut the night before. You might think I’d find that relatively easy: I’d reviewed the world premiere of the Morris “Dido” in 1989, I’d written about it on three or more later occasions, once in essay form, it’s a masterpiece I knew fairly well. But I began sketching my review on the Thursday night on the train back to New York, I’d arrived at the “New York Times” at 8am on Friday to start typing and re-working it; I knew it was one of those reviews that mattered to me in a big way - that it was taking me somewhere I hadn’t even before. I kept needing to rewrite, to restructure, to change. Deadlines at the “New York Times” were different on Fridays from those on other days. You could file a piece much later than on other days. Well, that Friday, the news broke that Michael Jackson had died. The “New York Times'' Culture editor, Sam Sifton, a fabulous man, said “I want you to write about Jackson’s dancing!” I said “I’m the wrong generation - I’m not sure how much of his dancing I’ve ever seen.” Quickly he said “What if we get our pop music critics to email you YouTube selections of his dancing?” I said “Okay, on the condition that, once I’ve watched them, I can let you know if I feel I’ve nothing to say.”

Well, I can’t even believe it happened this way, but I don’t think I’m exaggerating: I went on writing the Mark Morris piece, about a dance I already knew, for five or six hours, till 3pm: a thousand words. Then, only then, did I begin to watch the videos that the pop critics, Sia Michel and Jon Caramanica, had emailed me. Well, of course I realised at once I had somehow watched more of Michael Jackson over the years than I had ever known, and that I had something to say. But what was weird was that Sia Michel had sent me a bunch of videos from the second half of Jackson’s career, all of which depressed me; but Jon Caramanica had sent me a bunch from the first half, with which I fell in love.

I have a chronological mind, so I quickly sorted them into chronological sequence. And, while I watched that sequence, I could see what I wanted to say. I think I spent ninety minutes watching the videos, then ninety minutes writing the piece: another thousand words; filed by 6pm. (Thank heavens the editing on both pieces was swift that day: it wasn’t always!)

Anyway, you know what? The Jackson piece https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/27/arts/music/27assess.html felt as easy as falling off a log - and was one of the very biggest hits of my career, with hundreds of readers writing in as soon as they read it. Years later, it was one of the three pieces by me republished by Mindy Aloff in her Yale anthology “America Dancing” (really a Library of America anthology of best American dance writing - yes, I know I’m not American).

Yet only one reader, a friend who adored Mark Morris, commented on the review of his “Dido” https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/27/arts/dance/27dido.html , though that was the piece I was proud of and had worked on so lovingly and so hard. Whaddya ever know?

Bob Gottlieb has been a legendary editor for over sixty years; he’s also been a dance devotee since 1948. He’s edited Robert Caro, John Cheever, Len Deighton, Margot Fonteyn, Antonia Fraser, Joseph Heller, John Le Carré, Natalia Makarova, Toni Morrison, and dozens (or hundreds) more ; he was the man who thought up the title “Catch-22”. Well, one of his mottos is “Don’t think - type!” His point is that professional writers can usually write much faster and more fluently than they often let themselves.

Bob adores dance, but I’m one of the very few dance critics he’s edited - and I like to think I must have been the one who learnt most (had most to learn) from him. He was editor in chief to “The New Yorker” in 1997-1992; I spent two six-month periods as its guest dance critic in 1988 and 1992, when Arlene Croce took sabbaticals. He had edited Arlene, but she was already a superlative writer of whom he was in awe. I, on the other hand, was immature - I was thirty-two when I began there - and had everything to learn abort writing itself.

I didn’t know that, mind you. I’d been a critic for ten years; I took a certain pride that I knew what I could do with a sentence and a paragraph. Maybe for that reason I was an ideal person to learn from the whole “New Yorker” process: I already knew plenty but a whole lot less than I thought I knew. From the Old Style editors at “The New Yorker”, I learnt vast amounts about the composition of sentences and paragraphs (I think of them every day in my use of commas); from Bob, who was New Style, I learnt much else. Once, after he’d looked at a paragraph on which I’d worked half a day, he just said, softly, “This is just throat-clearing - we don’t need this.” About one verb in my first piece, he said, again quietly, “This is boring.” I said “I know, Bob, but I just can’t think of a better word!” Immediately, he reeled off six, like a thesaurus! At once, I then thought of two others, and told them to him. He said “Fine. Choose!” I chose. He exclaimed, “V.E! Verb Enrichment!” - gleefully.

Old Style editing, which he admired and practiced well himself, was about helping you to write correctly and more clearly; New Style editing, which he had spent years on at Knopf and, before that, Simon & Shuster, was about helping you to write more interestingly. Both sides have their controversies, but I was at the perfect stage to learn from both. My ninth or tenth essay was called “This World and Others.” The main editor of my “New Yorker” essays, the wonderful Ann Goldstein (now enjoying a more famous second career as the English translator of Elena Ferrante), asked me if I’d like to put a comma after the word “world”. I asked her to explain analytically the difference of implications between “This World, and Others” and “This World and Others.” She did: we spent several minutes talking it through. I added the comma. (Nobody there ever told me then that was an “Oxford comma”! But I’ve been addicted to Oxford commas ever since.)

So I was always interested in writing, and maybe I already had a feeling for it when I was at school and university. But “The New Yorker” made my instincts ten times as keen. Almost all my best editors have been American. Some of the line-editors at the “New York Times” were superb. (One of them bordered on genius.) In London, I’ve loved certain editors, and I hope have written good pieces for them, but the process was never so instructive or collaborative.

GM. For my generation, you were the dance critic of the “New York Times”, an Englishman in New York. How did that come about?

AM. Well, I was fifty-one when that job became vacant in autumn 2006. I’d been at the “FT” since 1988. I’d been its chief theatre critic - theatre not dance! - since January 1994. I was only covering dance in my spare time, mainly for the “Times Literary Supplement”. And I thought that (theatre for the “FT”, dance for the “T.L.S.”) would probably be my situation for the rest of my career: and a fabulous situation it was. For the “FT”, I’d reviewed world premieres by Alan Ayckbourn, Michael Frayn, Simon Gray, David Hare, Sarah Kane, Martin McDonagh, Conor McPherson, Patrick Marber, Phyllis Nagy, Harold Pinter, Mark Ravenhill, Wallace Shawn, Tom Stoppard, Timberlake Wertenbaker; I’d often reviewed Judi Dench, Vanessa Redgrave, Maggie Smith - the three actresses I called “miracle workers”. Despite what I’ve just said about the technical difficulty of describing and analysing choreographic musicality, acting is more or less as hard to write about as dance: it’s so multilayered. It’s much easier to find words for acting than for dance, but it’s really tricky to analyse what goes into the acting. And I loved that challenge. In some circles I’d become known as the critic who understood acting best, though I felt in 2006 I was only just beginning.

But John Rockwell - then dance critic to the “New York Times” (after many years as a music critic and an arts editor, and an exceptionally pleasant and generous colleague) - suddenly told the “New York Times” he would retire at the end of the next month. Their various experts and advisors began searching. One of their éminences grises, Charles McGrath, who’d been deputy editor of “The New Yorker” when I was there and who’d come to the “New York Times” as editor of its very prestigious weekly Book Review, consulted Bob Gottlieb; Bob, who’d recently visited me in London and with whom I stayed when I came to New York, thought of me. Because I was a very experienced newspaper writer, I was more qualified than most other American contenders. Because I’d reviewed New York dance for “The New Yorker”, I was more qualified than any British contender. Because I was still reviewing dance for the “TLS” and had come to New York to watch dance several times that century, I wasn’t a has-been.

I say all that now, but I was by no means sure I wanted the job. I was very grateful that London theatre criticism had given me a second career; my theatre reviews appeared in the “FT” far more often than the dance reviews of Clement Crisp. Balanchine and Robbins had died. And the “New York Times”, though it told me I was top of its list at the start of November 2006, then took three months before it offered me the job.

I remember thinking “Well, if it offers me less than A amount of dollars, I wouldn’t touch the job. If it offered me more than B dollars, I’d have to take the job.” Eventually, when the offer came in early February 2007, it was exactly halfway between A and B! So money wasn’t a decisive factor. (Some New Yorkers assumed I was paid literally twice as well as I was - they couldn’t imagine I would have come for less. Some Londoners pictured me in an apartment overlooking Central Park, which actually I couldn’t have afforded for a moment.)

Probably the big factor was just that I was fifty-one, a classic time for the midlife crisis, and here was this big paper inviting me to change my life at a time when most lives stop changing.

To be truthful, once I was in New York, I often felt I’d made the wrong decision. I never stopped being homesick for London theatre and my home in London. But I also call my “New York Times” years (2007-2018) the most interesting mistake of my life. I worked hard, I kept taking my own dance writing where it had not been (I was routinely given a thousand words several times a week!), I made many new friends, I reviewed dance in 22 states of the Union and in seven other countries, I found much to review beyond the usual categories of ballet and modern dance…. It was exciting; it was mind-expanding.

GM. You retired from that Chief Dance Critic position in December 2018. What has filled your time since then, global pandemic aside?

AM. I spent most of 2019 staying on in New York: I taught at Juilliard and at the 92nd St Y, I wrote monthly dance features for the “New York Times”, I was a fellow at the NYU Center for Ballet, I curated some educational presentations at New York City Center Studio 5, and I did a lot of research on Merce Cunningham (on whom I’ve been preparing a book for more than twenty-five years).

During the pandemic, I went on working for City Center Studio 5 from London: I curated two series of international online dance masterclasses. That was amazing: to get Nina Ananiashvili in Tbilisi to coach Sara Mearns in New York, as Odette in “Swan Lake” - live!- with me in London interviewing them both; and Alessandra Ferri in Milan coaching Misty Copeland as Juliet in New York. In 2022, I went back to New York to present two more Studio 5 events in person; in January 2023, I went to Phoenix, Arizona, to talk about “Giselle”. I began a website in 2020, on which I’ve posted a wide range of work (with more to follow). I’ve been reviewing classical music for the “FT” and “Slipped Disc” - a real privilege at a time when many music critics have been losing their jobs; I’ve written some super-long essays - on Balanchine, Cunningham, Nijinska, Ratmansky - for a new magazine, “Liberties”, and for the “New York Review of Books”. And yes, the Cunningham book remains in progress. I made one breakthrough in research during the period of tightest lockdown.

But we were speaking of your choreography! How has this progressed during your years at Northern?

GM. I entered our first choreographic lab under David Nixon and then again when it returned, this time my piece being selected to be developed into a dance film with mentorship from Kenneth Tindall. We shot on locations throughout Yorkshire and I collaborated with a DOP for the first time. It went on to win Best Dance Short at the New Renaissance Film Festival in London which was both a surprise and a delight. Here you are: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzkbJuZxssM

AM. Thank you! I have two immediate reactions to watching it. First: this is an intensely - excitingly - edited film, where the brevity of the takes create its own rhythm. I think that rhythm compliments the dynamics and phrasing of the choreography; I also think the tight framing of the camerawork makes the choreographic spacing more exciting. But I’m a theatre person: I’m curious about how this would work in a theatre. Is this a style you particularly use for the camera? Or one you use the camera to heighten?

Second: it’s very much in the expressionist style of “The Green Table” (Kurt Jooss, 1932). Is that a conscious connection on your part? I refer not just to the way the cast is seated around a table for negotiations but also to the staccato use of gestures, emphasising their finite arrival rather than a rhythmic flow of lower-body steps.

GM. No conscious connection on my part - but certainly it was choreographed specifically for capture in mind. When you are aiming for capture it can be camera-specific - a little like in the way that during particular scenes in my Snow White for London Children’s Ballet I knew what lighting I wanted first, then choreographed around that. Corridors of light carving out the space - dictating the trajectory of dancers or suchthelike. This is much the same, working in a way where you could almost say one prioritises another art within the art. That can be a fun experiment and one I enjoy.

“Pinocchio”, for Northern Ballet, came next, a forty-minute production specifically targeted at children and their initial introduction to live music and dance. The calibre of creative team on side for this project was high, so I was really inspired by it all and learning a lot. I don’t know if it was anything extraordinary, but the audiences seemed to like it and I was proud of what we achieved.

More recently, I made a new narrative work, “Assembly Line”, for Images Ballet Company at London Studio Centre, under the direction of Larissa Bamber, set to Copland’s timeless “Appalachian Spring Suite”. Performed at the Lilian Baylis Studio Theatre following a small tour, it dealt with themes of community and loss in a wartime Britain. Narrative, but more conceptual.

AM. Now, more than a month after we began this conversation, April 13 brought the world premiere of your “Snow White” for London Children’s Ballet at The Peacock Theatre. It’s new, it’s full-length - in two acts - and it’s very vividly danced.

GM. It’s my biggest commission yet; I’ve found it hugely exciting. I’ve reimagined it - a new plot and some interesting surprises along the way. There are fifty dancers, ranging from ages nine to fifteen and sixteen; they’ve really put their souls into it.

AM. Among the less important aspects of the world premiere, you and I met for the first time! But too briefly. I had a very good time, and was really impressed by how good you made all your dancers look. I’ve lots of questions.

Tell me about the score, which is by Ian Norriss but has been revised by Ian Stephens, and which was played live. When did Norriss write the original score? For whom did Stephens revise it? If you were involved at that stage, how did you collaborate with Stephens? I’m guessing Noriss wrote a more conventional “Snow White” with Disney-type dwarves?

GM. Norriss wrote the original score in 2009 in the original production created by Olivia Pickford. It was performed and revised again in 2015 with additions by Jenna Lee in somewhat of a reimagining, and then revised by Ian Stephens for me this year. I cut and pasted some of the music - for example the Prologue in my version was originally music for divertissement in Act II - but nothing said fairytale to me like that music - it had to be my prologue. I found reimagining the plot meant the music had to change in some ways to accommodate what I wanted to achieve narratively. It was risky, but I think it worked.

Musically, so much of the original score remained. For example, the first scene in Act II where we introduce our Huntspeople was originally the music for the dwarfs. The same playful characters came out in our Huntspeople, so it worked. Ian worked with me on new music - for example, The Escape, a scene towards the end of the show where the Dove flew furiously back to the castle to rescue our leading man and bring him to save Snow White. This included a battle between the Dove and Raven, glorious music for five ‘Stags’ and more. He, Ian, did an amazing job of honouring what Richard had done and added to it. That’s the beauty of art - it can always be evolving - improving. I suppose a work of art is never really finished for an artist.

AM.The designs are marvellous: very picturesque, pretty, colourful, but always complementing the show without stealing attention for themselves. I see the original costume designs were by Sarah Godwin: when were those made? What’s new here? I’m especially impressed by the series of curtains/dropcloths that take us to different parts of the forest and the court, often in very quick succession, but all advancing the story. Some of the forest backcloths are the prettiest designs in the whole show, with wonderful two-dimensional landscapes suggesting different depths, zones, lights. Were you part of the process of choosing and commissioning the new designs?

GM. Our technical manager, James Smith, curated the entire set as well as co-ordinating the production. This cost-saving initiative did concern me at the beginning of the process but, as you explain above, worked beautifully. James did a brilliant job. We spent many a zoom meeting looking at different cloths and designs from scenic hire companies. I was very ambitious in the amount of cloths and set I wanted. LCB, London Children’s Ballet, actually had to hire extra fly men for the fly floor because there were so many cloths which had to move at such speed to keep the narrative flowing. There wasn’t a single free bar on the fly plot! I asked a lot of every part of the team… but it came together to offer something unique and successful.

AM.When did you begin preparing the production? What was involved before you began rehearsals?

GM. I began preparing the show in August last year. There was a significant amount of planning and preparation which went into the show. Specifically around rewriting the scenario, understanding how I wanted to pitch my new characters and plot lines, whilst rearranging the music. Then came auditions - 600+ children from across England and finding a company which could tell our story. Casting followed, such a challenge but in retrospect I wouldn’t change a thing.

AM.The whole show is about story, and yet you structure it as a dance event, with dances for more or less every character. Each dance is in character - this group of five children dances this way, that group of four children dances that way, and there are any number of characters who have solo opportunities. You don’t ask the children to do too much pointwork - but their footwork is all vivid, precise, varied. When did you begin rehearsing with them?

GM. Yes, lots of dancing and an awful lot of footwork. Particularly in our Snow scene and party scenes, I could show off the talent of our strongest technicians. We began rehearsals in January. One rehearsal a week on Sundays - then 2 “intensive” weeks where we had the company for six consecutive days. It was a very tight turn around…but the young people’s exponential growth as story tellers and technicians was quite something. We were bursting with pride watching them perform to the level they did. It was nothing short of elite for their ages.

AM. What comes next for you?

GM. After that - a new, original narrative work for Elmhurst Ballet School in Birmingham as they celebrate their centenary. This project will include the entire lower school with lots of talented young people to work with.

AM. Tell me about the challenges of making pure dances and of making story ballets - the challenges for yourself, that is.

GM. Creating story ballets is about going beyond creating pure dance, I think. A lot of planning goes in to making narrative work.

You’re making steps, but they need intention or indeed they need to stem from the narrative concepts you want to present. How do we dance in a way that conveys what we need to say, continuing the arc of the story? How can we better refine our choreographic language to say what we need it to? These questions are what excites me about the process of making narrative work. The challenge is getting the balance right and interweaving strong moments that communicate what is happening to the characters.

AM. Watching “Snow White”, I’d have guessed you work the other way round: that, although every movement is characterful, you seem keen to provide as much dancing as possible, to keep changing the dance mood and pace, even with the snow and court ensembles. Nothing gets stuck in a “character” rut. You give us geometries and rhythms that keep changing, and steps that really release these young dancers’ abilities. Do you disagree?!

GM. I’m touched you thought so. Indeed the scenes you mention better facilitate me showing off their dancing, but for the most part story came first in “Snow White”. So narrative-centric it had to be that way. In my new ballet for Elmhurst, it’s slightly different. I’m telling a story but sometimes in more conceptual ways. I found it easier to “make steps” in that process and in some ways the steps led the narrative.

AM. Dancing is one thing, but performing is another. I guess that some of your child dancers are natural performers, but did you work on some in terms of projection? If so, how?

GM. We worked massively on them in terms of projection, acting and approach to the work. For the first time, we asked LCB to offer morning classes before our rehearsals to also have the opportunity to get the young peoples bodies warm and ready for their rehearsals whilst refining their technical abilities. We coached and coached to get the soloists to where they got to… Bigger, longer, further…I pushed every step of the way to get as much out of them as possible. The results corroborated the importance of doing that.

AM. And acting. British dancers tend to be instinctive actors if the climate is right - the Royal and Northern and New Adventures are among the British troupes that are all havens for dance actors - but not all children (and not all adults) find their characters easily. Here, you’ve got characters wicked and good, funny and poignant, human and supernatural, royal and plebeian.

Do you have ways of helping the dancers to find their characters? It actually looks, in a good way, as if you’ve given them the steps that will help them find their characters: I loved those fast, hopping arabesques voyagées and big sauts de basque for the Queen - the steps themselves seemed to convey the intention and the role. But how did the process happen?

GM. There is definitely a language for each character in there and I loved building that language and making them distinctive. We used word banks for the dancers, talked about “how” they would move and their thought processes. We posed questions, made them take ownership of their choices and their roles. When they bought into it, deeply understanding who they were, where they have been and where they were going - it became easier to make. Everything starts clicking into place at that point.

AM. Which choreographers do you feel have influenced you?

GM. Akram Khan, Jean-Christophe Maillot, David Nixon, Crystal Pite, Kenneth Tindall, Christopher Wheeldon, to name a few, in alphabetical order.

AM. Can I get you to enlarge on one or more of them? Can you word what you admire in them and/or what you have taken from them?

GM. All of these artists are top-notch story tellers. They make me, as an audience member, ask questions; they present clear ideas visually but usually in ways I hadn’t considered could be possible. Dancing Jean-Christophe Maillot’s “R&J” and having him and his team in the studio with us was a career highlight. Narrative comes so second nature to him. The movement just laces so naturally with what he’s trying to say. It feels familiar, relatable and assimilates with audiences. Sometimes I am watching his work and think “Wow, that’s so clear”.

AM. And are there choreographers whose work you love but which hasn’t yet influenced your own?

GM. I think everything we see and do influences us and the decisions we make. The questions or ideas prompted by the things we see in theatres or on screen are so important. That is whether they make us think “Wow, that was such a bad choice” or “Gosh, I wish I could make dance that says that with this level of originality”.

I try and keep my worldviews as open as I can, vary my life experiences and my consumption of the wider culture sector. It all better informs what I go on to make or produce on stage as an artist for audiences.

AM. I note from Instagram that you’re a great traveller. And yes, travel does broaden the mind.

I also find you exemplary in the way you present on social media your long term relationship with your offstage partner and fellow Northern dancer, Kevin Poeung. You don’t trumpet gay liberation as an agenda, you just show yourselves as liberated that way. Being maybe forty years older than you - I’m sixty-seven - I’d say this openness about same-sex relationships is, in the dance world, something of this twenty first century. Of course there were gay dance couples back in the twentieth century, but (apart from the amazing Diaghilev) generally there was a convention never to draw attention to their private lives. Do you still feel that you’re exemplary in this way? Have you encountered problems or hostility for your sexuality or at least for your (very in aggressive) openness about it?

GM. That’s so kind of you. I think as a boy I spent so many years pretending to be a more socially-accepted version of myself that, once I decided I knew who I was and told the people I loved, it became about trying to live authentically whilst somewhat unpicking the more difficult years of spending parts of my childhood embarrassed about who I was. There is no greater resistance to any kind of bigotry than just being yourself, being kind to everyone around you and putting the good honest work in.

AM. Do you, as a dancer, like reading reviews of yourself? I know that most performing artists do read their reviews, but I’m still inclined - with a very few exceptions - to feel that Edwin Denby was right in the 1940s to write that reading reviews of oneself is a waste of time (“like smoking cigarettes”). Reading reviews of other artists, he added, might be better. Reviews are like part of a conversation between members of the public;, so, for a dancer to read reviews is like eavesdropping - obviously provocative but almost never of real use.

GM. I do indeed read reviews of my own company’s work and of others, mainly because opinion interests me. Particularly when it’s opinion on work I feel has value. Whether someone has loved or hated a show we’ve put on or not is not important per se. I like to understand what people have taken away from the experience as distinct from what I feel we have tried to give them - be that as an artist on stage or as the choreographer.

What has been your favourite piece of your own writing to date - and why?

AM. I don’t spend much time looking through my old pieces. Sometimes (not often), I come across old reviews I wrote, only to find that I simply don’t remember having seen having seen those shows at all. Sometimes (not infrequently), I shudder at infelicities or blunders in my prose. But favourites? Hmmm. Well, here are a few contenders:-

In 2006, I wrote an essay “Pinter’s Women” in the “Times Literary Supplement” that excited Pinter himself: I kept meeting people whom he’d told to read it. That was maybe the biggest compliment of my career.

In 2007-2009, I was able to write a whole series of reviews and essays for the “New York Times” about Merce Cunningham’s work as danced by his company while he was still alive, and then to go on doing so in 2009-2011 after his death until the company closed. That was a big adventure, because Cunningham’s choreography, even though I’d been watching it since 1979, just went on giving me more things to see and to say. Merce himself never remarked on my reviews of his work (he let me know he liked my reviews of other dance, especially dance about which he hadn’t known - the flamenco dancer Soledad Barrio, the African American downtown choreographer Reggie Wilson - but there was one review of a Cunningham Event https://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/09/arts/dance/09merc.html “Being Alone Together in Cunningham’s World” (December 8, 2008), an Event that featured male-female duets, that prompted his most famous dancer, Carolyn Brown, to write to me, saying that she felt I’d hit on something true about the nature of love in Cunningham that nobody had said before.

In 2013, American Ballet Theatre presented the world premiere of Alexei Ratmansky’s “Shostakovich Trilogy” at the New York Met. Strictly speaking, it was the world premiere of two thirds of the trilogy: we’d already seen the opening ballet. It was a highly imaginative study of Shostakovich the creative artist in the oppressive context of Soviet society. At some level, I’m always nervous before reviewing a premiere - it’s a great responsibility - even though the trick is to be as relaxed as possible. That night, various things made me far more nervous than usual. And as a trilogy it was unprecedented: it told no overall story, and it dramatised Shostakovich’s inner world in three quite different ways. When my review appeared (“Wit, Poetry and Shadows” https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/03/arts/dance/ratmanskys-shostakovich-trilogy-at-american-ballet-theater.html June 2, 2013), I won compliments from a surprising range of fellow-critics who admitted that they hadn’t “got” the trilogy but that this review had helped them to do so.

That’s more than enough of me blowing my trumpet for you! There are pieces by Denby and Croce to which I return far more often than anything than anything by myself. One example is Denby’s 1952 essay “New York City’s Ballet”; another is Croce’s 1975 essay “Free and More than Equal”. But I could name dozens by each of those two writers.

GM. Do you still get a thrill from seeing your words published? I know the feeling never got old for me in my time contributing to the “Dancing Times”.

AM. Well, I do remember that thrill from my first fifteen years and a half. I remember getting up early once in 1980, so that I could read one of my first reviews for “The Guardian” as soon as it reached the local newsagents at 7am or earlier.

But in January 1994, when I became the “FT”’s chief theatre critic and was often being published four times a week, I found myself actually scared. The review had a life of its own. Sometimes it was the cause of controversy; sometimes it was quoted in part or reproduced as a whole outside the theatre; sometimes people assumed you’d written a more negative or more positive review than you’d intended. With theatre, reviews often are interpreted in powerfully commercial terms - they’re said to close a show after a few performances or to prolong the life of a production that the management did not foresee as successful. So i would open the paper an inch just to see if the review was on the page, then I’d close it again until I got any feedback from readers, if I did.

When I moved to the “New York Times”, there was usually at least ten times more feedback from readers. I would be excited if the review was on the front page of the Arts section in the print edition, especially if it was “above the fold” - but I still felt that the piece was a mystery to me until I sensed what effect it had had on readers. Is this one going to be like that review of the Mark Morris “Dido”, making scarcely a ripple? Or is it going to be like that one of Michael Jackson, causing what felt like an unexpected tsunami? In advance, you can have no idea. Posterity will decide that this review or that review is important or unimportant. But I’ve been around long enough to know that posterity can be wrong!

I’ve never seen you dance, but you read my reviews of other performances. Not all dancers read reviews of other companies and other dancers and other dance genres, by no means all. What makes you read reviews of other dancers?

GM. I think a curiosity about other work, how it was received and to understand the art form better. I’ve always been intrigued by the breadth of work presented on stages throughout the world. Tapping into those experiences was possible through reading about them through a critic’s lens.

You’ve had some controversy over the years. Do you feel you always approached your critiques and articles with authenticity and kindness?

AM. You’re probably remembering my most notorious review, the 2010 review of New York City Ballet’s “Nutcracker” opening night. I don’t think anyone has ever commented on the first twelve paragraphs, of which I’m certainly proud; but they’re not seen as controversial. Near the end of the review, however, I wrote that the Sugar Plum ballerina seemed to have eaten “one sugar plum too many”. For the next five weeks, that went viral, especially after Jenifer Ringer, the ballerina in question, went on a TV talk show about it. On my website, www.alastairmacaulay.com , you can find the “Sugarplumgate” essay I’ve written about that whole episode.

Because there was an international brouhaha about my choice of words, you may not believe that some people felt I was restrained. But the very first response to that review came from a fellow-critic who’d been watching City Ballet far longer than I and who had kept complaining about how boring Jenifer Ringer and Jared Angle were. In the past, he’d been furious that I’d sometimes written complimentary reviews of each of them. But now he chose to email me to say that my words about those two were “very sensitive”.

As I’ve said before, I only wrote those words because, at that performance, a voice in the audience after the pas de deux said, firmly, “God, they’re fat!” and because my companion, when I consulted her, firmly supported that view. Otherwise I had no reputation for writing about women being overweight (I’d mentioned three or more men’s being overweight, but those were men who were very obviously on the plump side).

What I regret now is that I’d never made an issue of some women being too skinny. I don’t know that there’s an eloquent way to address that, but I realise that, throughout my career, I’ve been bothered by the somewhat skeletal physiques of some women dancers; and I wish, perhaps without naming names, that I’d shown that I took no pleasure from watching that degree of skinniness.

Let me ask you about two words you used just now. I don’t know what you mean by authenticity. Sincerity? I always tried for that. Over the years I’ve spotted insincerity in several critics: some of them were afraid to say what they meant, some of them were keener to be popular than to be honest. Most critics like to believe they themselves are not corrupt, but I think companies know all kinds of ways of buttering critics up, sometimes in ways that seem harmless. Over thirty years ago, a British dance company executive called me to invite me to have a good meal with him, at the company’s expense, because (he put it bluntly) all the other critics were now writing glowing reviews of that troupe. I remember saying “I’d be very happy to change my mind about your company. But I need to have it changed by its performances, not by what I see onstage.”

That makes me sound virtuous, but I bet I’ve been buttered up a few times without realising. One of the cleverest methods is for a director or a press officer to compliment you on the most negative part of your last review. You’re touched that they’re commending your honesty. What you don’t notice is that their compliment softens you up! And the effect tends to be that your next review is less negative. They’ve got you on their side without your noticing.

As for kindness, no. Kindness to whom? I write for other members of the audience, many of whom welcome tough-mindedness. I’m one of several critics who’ve used sarcasm, but I’ve known non-critics speak with greater sarcasm and more scorn. Some of my reviews must seem unkind to people who don’t agree with them, others very kind.

Sincerity is remarkably hard to achieve. There are so many things to write about any performance: it’s hard to balance them judiciously. Critics often feel, with good reason, that they don’t know what they feel about a production until they’ve written their review. Certainly I’ve often felt that writing the review has helped me to describe and analyse much of what I felt at the time.

But occasionally - I hope not often - I think I’ve under-emphasised some feelings and over-emphasised others. In this sentence, I was on a bigger roll than I really should have been; in that paragraph, I neglected to address a point that actually struck me while I was watching and listening. I think I’ve spotted a number of critics do this; and it’s often the critics who are the best writers. They know how to turn on the charm of their own prose without too much effort; but addressing all the nexus of conflicting feelings in the performance takes a rigorous precision they - we - can’t always manage. Does any of this make sense?

Gavin, do you long to write reviews yourself when you watch other dancing?

GM. I can’t say I long for it; but I’d love to give it a try with a commission someday. I have never had a review published, only interviews or opinion pieces. I find opinion tends to be valued more when people are in the later stages of their lives. Personally, I enjoy following the work of younger critics like Emily May, who writes for “Dance Magazine”, and Isabelle Brouwers, a friend who writes with such clarity via “Dance Europe” but also on her Instagram, @isabelle_insights, on a wide range of dance and theatre work.

AM. It’s often invaluable to read the voices of one’s own generation and/or the artist’s own generation. In 1983-1987, Arlene Croce wrote some “New Yorker” reviews that did much to put Mark Morris on the map. She wasn’t the first to praise him, but she wrote of him in ways that brought him and his work to fascinating life for thousands of readers around the world. In 1988, standing in for her while she took her six-month sabbatical, I wrote my first long Mark Morris review. Arlene’s immediate response was to say how good it was to see how much more Morris meant to his own generation (I’m a year and a month older than him, whereas Arlene is twentyone years older than I). The 1980s were years in which a number of modern-dance choreographers addressed same-sex coupling far more openly than their predecessors. Morris did that enchantingly; I welcomed it - whereas the more socially conservative Arlene, although she had praised him in very high terms, could admire and acknowledge that but not love it.

Now I’m in the senior-generation situation that Arlene was in then! I’ve praised a number of choreographers younger than I - Ratmansky, Pam Tanowitz, Liz Gerring, Justin Peck - but it may be that younger viewers connect with some of their values in ways that elude me.

GM. For me, younger voices are a key component of important conversations and critical work. Often missing from board rooms and critical forums, young people’s views normally go unheard. This is why I so valued the platform Jon (Gray, ex-editor of “Dancing Times”) gave me.

I know you have a wide interest in the wider world of art - how has this fed in to your writing on dance?

AM: Dance always exists in one larger context or another, doesn’t it? Arlene liked to say “Who knows dancing who only dancing knows?” - and to say that that was her motto. Well, I made it my motto too. I’m all for dancers becoming critics. Denby was a dancer before he was a critic.

But every dance critic has to remember they’re not just reviewing dancers and choreographers. (When there’s live music, the musicians are often the best paid people involved!) Dance can be poetry, it can be drama, it can be politics, it can be painting, it can be religion. We just have to keep our minds open to the possibilities.

1: Gavin McCaig

2: During the run of Northern Ballet Theatre’s “Nutcracker”, McCaig (right) and Matthew Topliss (left) lift Natalia Lerner backstage.”: three Arabian dancers.

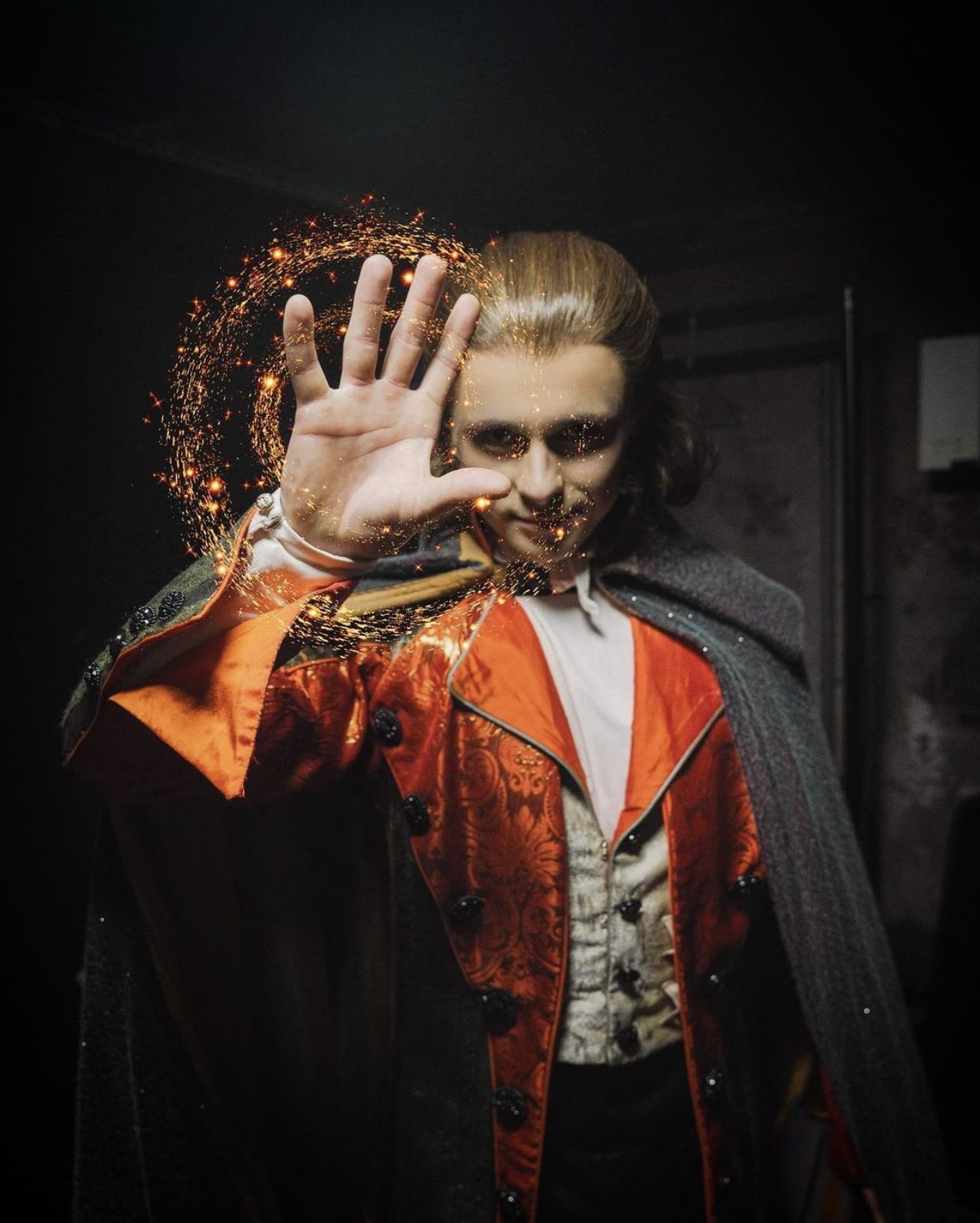

3: Gavin McCaig as Drosselmayer in Northern Ballet Theatre’s “Nutcracker”.

4: McCaig as Drosselmayer, Northern Ballet Theatre.

5: McCaig rehearsing London Children’s Ballet dancers for his “Snow White”

7: McCaig rehearsing London Children’s Ballet dancers for his “Snow White”

8: McCaig rehearsing London Children’s Ballet dancers for his “Snow White”

9: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, London, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

10: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

11: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

12: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

13: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

14: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

15: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

16: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

17:

London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

18: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

19: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

20: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.

21: London Children’s Ballet performing McCaig’s “Snow White” at the Peacock Theatre, April 2023. Photography by ASH.