“Word-Play”, politics and words at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs

I.

Rabiah Hussain’s new “Word-Play” is semantics as drama. The play builds variations on individual words: river, waves, blood, normal, different, stones, bones, colour…. It’s a play in multiple scenes, many of which introduce different characters, all of them nameless; but all of them occur in an England that’s highly, hilariously, and painfully recognisable. Race and language are such vital issues here that you want the Home Secretary, every civil servant in the Home Office, and every British politician to see it at once. At first, “Word-Play” seems merely clever, and merely satirical, but soon enough you see - you hear - that it’s much more. In this England, words and their meanings are bounced around, now like an absurdist divertissement, now like political dynamite.

The racial dimension of words is apparent from the opening scene, “Rivers of Blood”, spoken by male voices over an empty stage. At first theirs is merely talk about talk, giving names to moments. Metaphors that arise amid all this talk are ripples, waves, rivers, blood, until finally we hear the phrase “rivers of blood”. My generation can hardly forget that “Rivers of Blood” is the name given to a celebrated speech given in April 1968 by the Conservative politician Enoch Powell (I was twelve) - even though Powell, in context of his alarm about mass immigration, specifically from former Commonwealth countries to the United Kingdom, spoke not of rivers (plural) but of one river alone:

“As I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see 'the River Tiber foaming with much blood'.” Since then, “rivers of blood” has been a metaphor for racially based civil warfare.

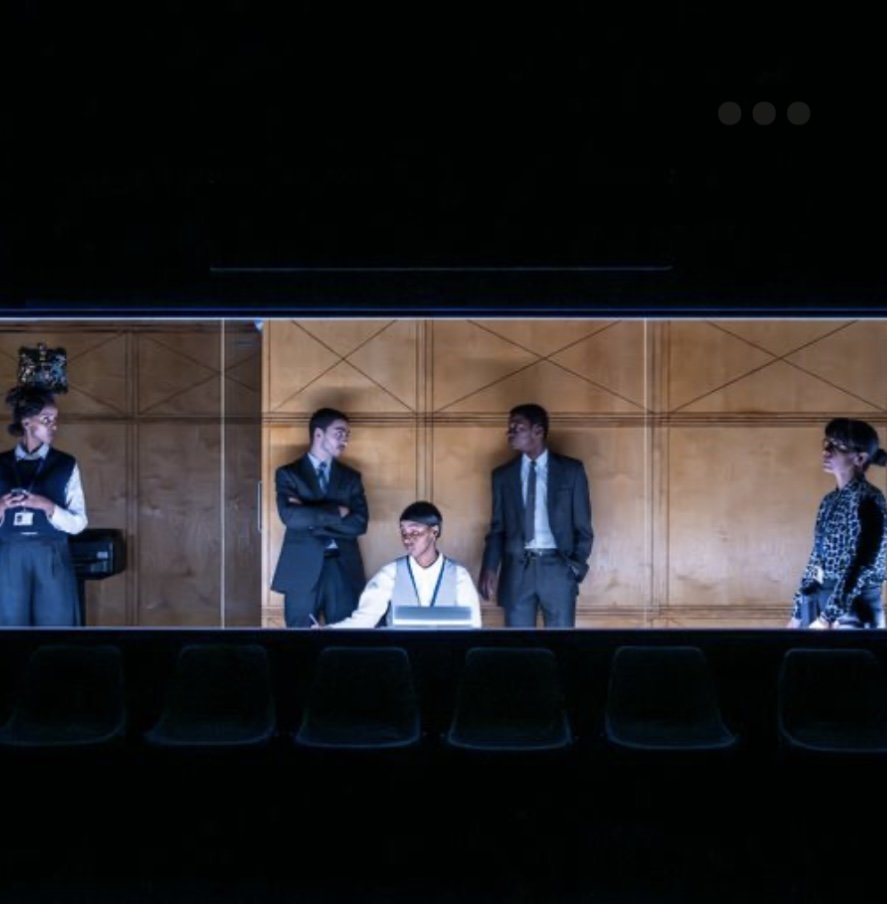

At first, however, “Word-Play” passes lightly over that echo. Instead it moves to the comedy of the Number Ten Downing Street press office reacting in alarm to a divisive speech made by (we presume) a Prime Minister. (With so many recent PMs, let us not detain ourselves with speculation about one PM being more implicit here than another.) Nobody in this Downing Street Press Office is bothered by the actual sociopolitical intention of their leader’s words, though gradually it emerges they were racially loaded. These lackeys are focused only on spin, on how how the leader’s words can be handled. We mustn’t say he’s sorry, but let’s find what alternative wording might solve the problem. Let’s check how all this blunder is being reported in the media outlets, in the blogs; let’s counter that by drawing attention to anti-semitism in the opposition party; let’s scour social media for expressions of support (yes, here’s one from China). The whole scene is funny, silly, even though we can’t miss that it’s the absurd face of a dismaying larger politics.

In another scene, a man comments on the wording of the ubiquitous British poster and message “See It. Say It. Sorted”. He: “So, if I see something… I say it? And then it’s sorted?” (Thank heavens someone is commenting on this appalling propaganda.) It is explained to him that he is to look for - and report - whatever is not normal, whatever is weird, whatever is suspicious. “You know what ‘normal’ is. We all know what ‘normal’ is. I know it. You know it. They know it.” Having ascertained that we are to prevent whatever is not normal, he asks, “And that’s the strategy?” No, comes the reply: “That’s the duty.”

We can enjoy this as comedy because everyone in Britain knows the Orwellian absurdity of the “See it. Say it. Sorted” message. But “Word Play” moves on through many scenes - domestic, social, academic, political. Dinner parties, research students, followers of the faith, members of a theatre audience. The many roles are taken by five actors (three women, two men).

Ultimately one woman, a British citizen of colour (played by Yusra Warsama), relates, in one quiet, sustained monologue, how she took her daughter Iman (the name means Faith) to meet her grandparents in their country for two weeks; when Iman returned in England, she was interrogated at school about the little stones and pictures and words she has brought back from her grandparents. The suggestion is that the child Iman is now to be considered a dangerous foreign agent. The experience destroys the child’s innocence; the mother’s, too. “Word-Play” has turned tragic and horrific.

In a moving two-page introduction to the printed edition (Nick Hern Books), Hussain writes how her life was changed by the experience of aphasia, after an operation to remove a brain tumour; how she learnt the power of language by (temporarily) losing it. She goes on to say, “When policy around language is changed and shifted to equate language with how ‘good’ a citizen you are, we arrive in a place where verbal stones are thrown at certain communities, who then are asked to forgo their mother tongues for the more ‘progressive’ and ‘normal’ languages of the countries they now live in. Multilingualism becomes a negative thing. And it is monolingualism that is then tied to nationalism.”

“Word-Play”, which lasts ninety minutes, is an important premiere in terms of politics as well as theatre. It’s in repertory at the Jerwood Royal Court Theatre Upstairs until August 19. It’s plainly in the lineage of plays by Harold Pinter (notably “Mountain Language” and “Party Time”) and Caryl Churchill; and it brilliantly refreshes the reputation of the Royal Court for theatrical excellence. Nimmo Ismail directs vividly, so that the space keeps changing: the audience sits on three sides, but the actors sometimes move behind the audience or sit beside them. The five actors - Issam Al Ghussain, Kosar Ali, Simon Mayonda, Sirine Saba, Yusra Warsama - show the fun as well as the anguish within all the situations. My main cavil is that Ismail’s production sometimes relies too much on its music and sound score (by XANA) to build up sonic effects of suspense and doom.

II.

When I was in my teens, my idea of political theatre was taking my parents to see a drawing-room comedy by William Douglas-Home in which various more or less upper-class characters had time in which to be amusing and endearing about the three or four main candidates at the local by-election. And in the interval, tea was brought to our seats on a tray. (I’m not making this up. My parents and I did see Ralph Richardson and Peggy Ashcroft in Douglas-Home’s “Lloyd George Knew My Father” at the Savoy Theatre in summer 1973, when I was between school and university. Tea really was brought on a tray, at our request.)

Probably there are still people who, while going to the theatre, can avoid political seriousness as I certainly chose to do in those days. And British theatre still goes through periods when politics enters too little into its nervous system. Just now, however, I’m happy to say the opposite is true. I came to “Word-Play” after the matinee of James Graham’s “Dear England” at the National Theatre’s Olivier auditorium: Joseph Fiennes and Gina McKee lead a large cast, directed by Rupert Goold, that takes the recent fortunes of the English soccer team, as managed by Gareth Southgate (Fiennes), through a long and serious investigation of issues that include race, history, psychology, and politics. Two days earlier, I watched Peter Morgan’s “Patriots” at the Noël Coward Theatre: Tom Hollander is Boris Berezovsky, Will Keen is Vladimir Putin, Luke Thallion is Roman Abramovich. New at the National is “Grenfell: in the words of survivors”, the second verbatim drama about the Grenfell Tower disaster of 2017. At the Park Theatre is Andrew Stein’s play about AI, “Disruption”. These are by no means all.

III.

It’s good to be back at the Theatre Upstairs, one of London’s most spatially flexible stages and auditoria, seating maybe a hundred. My memories here go back over thirty years, often to premieres of plays by women: “Weldon Rising” (1992) by Phyllis Nagy, “Credible Witness” (2001) by Timberlake Wertenbaker, and “The Sugar Syndrome” (2003) by the then unknown Lucy Prebble come to mind. Twenty years ago, I was told that a play receiving its world premiere here could soon expect a dozen subsequent productions on the European continent. Has Brexit changed those statistics? Although “Word-Play” is targeted at the U.K., it applies to social and political - and linguistic - conditions around the world.

@Alastair Macaulay, July 27, 2023

1: Simon Manyonda in one scene of “Word-Play”. Photograph: Johan Persson.

2: Simon Manyonda, Kosar Ali, and Sirine Saba in one Number Ten Downing Street press office scene of “Word-Play”. Photograph: Johan Persson.

3: Kosar Ali in one scene of “Word-Play”. Photograph: Johan Persson.

4: Kosar Ali in one scene of “Word-Play”. Photograph: Johan Persson.

5: YusraWarsama in one scene of “Word-Play”. Photograph: Johan Persson.

6: Another Downing Street press office scene of “Word-Play”. Left to right: Yusra Warsama , Issam Al Ghussain, Kosar Ali, Simon Manyonda, Sirine Saba. Photograph: Johan Persson.