Arthur Mitchell - Black History Month in Dance, 2021

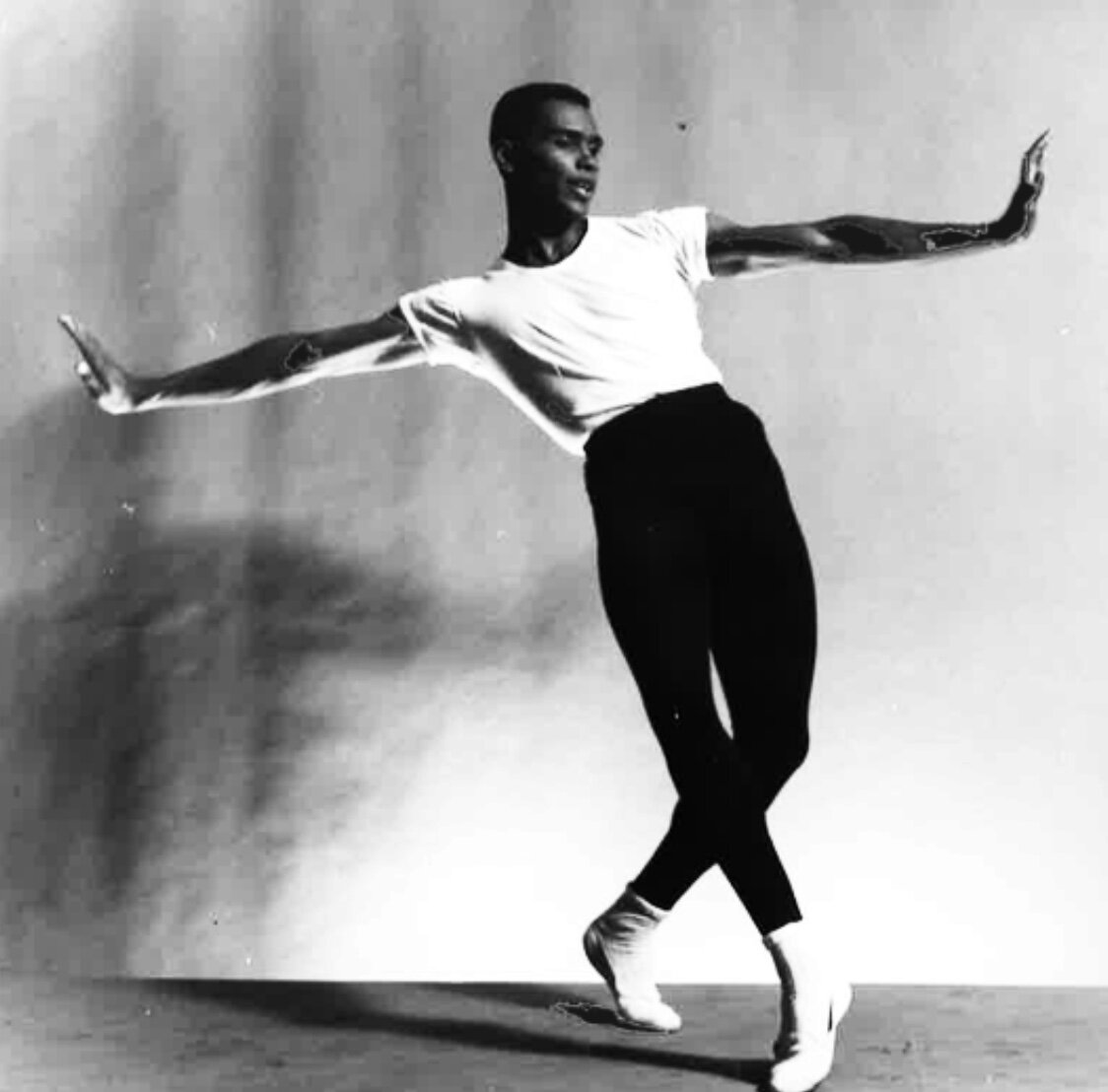

32; 33; 34; 35; 36; 37; 38. For Black History Month in dance, here’s the fabulous Arthur Mitchell (1934-2018). Like the slightly older Louis Johnson (24 in this series), Mitchell danced in the Broadway show “House of Flowers”, both men making friends for life with other cast members. In 1955, he was the first African American dancer taken into New York City Ballet as a company member; in 1957, George Balanchine gave him and the ballerina Diana Adams the climactic pas de deux of the new Stravinsky ballet “Agon”. Tall, beautiful, and devoted to the teaching and choreography of George Balanchine, Mitchell created other Balanchine roles (notably Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, 1962 - see 36 - and the Hoofer in “Slaughter on Tenth Avenue”, 1967) before co-founding, with Karel Shook in 1969, Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Today, the “Agon” casting of an African American man with a white ballerina has made that ballet seem a crucial achievement for the presentation of the races. It was indeed, but it was not without precedent; and it’s remarkable that this element in 1957 was underplayed in critical discussion of the ballet. Balanchine’s ballets are multi-layered; he took fascinated care with the precise placing of Mitchell’s black skin on and beside that of Diana Adams, but partly for musical reasons - that pas de deux is where music’s black and white notes are mixed in new ways. Balanchine, however, certainly knew the interracial and cultural significance of casting Mitchell: in 1958, he rearranged the Sugarplum adagio in a television special of “The Nutcracker” so that Mitchell (dancing the role of Coffee) was one of the four men to partner Diana Adams (the Sugarplum Fairy); Balanchine told Mitchell “This is for Governor Faubus!”, referring to the Governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, whose 1957 stand against racial desegregation in schools had become a vexed national issue.

It is impossible to underestimate the impact of Dance Theatre of Harlem, under Mitchell, within and beyond the United States. On its first visit to London, in 1974, it was singled out for a level of musicality beyond all other dance companies by the critic James Kennedy Monahan in “The Guardian”; between 1979 and 1985, it was the American dance company that visited London far more than any other, dancing at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, the Royal Opera House, and the London Coliseum. In a 1983 season at Covent Garden, I remember that its virtues of clarity, rhythm, line, and phrasing showed it to be a more luminously classical company than the Royal Ballet. And, marvellously, it brought an enthusiastic black audience to those theatres. The company danced a wide range of Balanchine ballets: its “Agon” was widely felt in the 1970s to have restored the edge that that ballet had lost. I remember what knockouts the company’s “Serenade”, “Concerto Barocco”, and “The Four Temperaments” often were; but the company also danced its own productions of “Giselle”, the “Paquita” grand pas and “Swan Lake” Act II (both staged by Alexandra Danilova), “Scheherazade”, and “The Firebird”.

Mitchell knew how to make stars. Lydia Abarca, Ronald Perry, Virginia Johnson, Mel Tomlinson, Lorraine Graves, Eddie Shellman, were just some of the names that created intense buzz across the ballet world. Mitchell himself was a perfect ambassador; he took great pride in having welcomed members of the British royal family to Harlem’s performers and to its New York headquarters.

Of course there were controversies, some of them raised only out of print: many of the Harlem physiques were different in outline as well as colour from the white ones in many ballet companies. (Some of the company’s other repertory was widely deemed atrocious by us ballet connoisseurs, and warmly greeted by the company’s general audience.) Those were important debates for everyone to work through; I’m sorry that Dance Theatre of Harlem has not carried the same prestige in recent decades.

The photographic portrait 38 is by Debra Seibert; 33 (the tucked-up jump), used as a logo for Dance Theatre of Harlem, was taken by Martha Swope; I’m afraid I cannot find credits for the others. 32 and 34 show Mitchell in “Agon”, 34 with Allegra Kent; in 35, he is dancing Phlegmatic in “The Four Temperaments”; 36 shows him as Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”. In 37, he is teaching young students at the Harlem school. When I worked in New York in 2007-2018 for the “New York Times”, I met Mitchell a few times, always with delight and humour - and, on my part, intense admiration. I last saw him, a few months before his death, at the ceremony opening the exhibition with which he donated his archive to the University of Columbia; he was so robust and proud that it was a shock to hear of his death that same year.

Sunday 7 February

Arthur Mitchell in George Balanchine’s “Agon”, 1957

Arthur Mitchell, photo by Martha Swope (used as logo for Dance Theatre of Harlem)

Arthur Mitchell partnering Allegra Kent in George Balanchine’s “Agon”

Arthur Mitchell in the Phlegmatic solo of George Balanchine’s “The Four Temperaments”

Arthur Mitchell as Puck in George Balanchine’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”, 1962

Arthur Mitchell with young students at the Dance Theatre of Harlem school

Arthur Mitchell; photograph by Debra Seibert