Is Mary Wigman’s dance modernism still a fact of history?: Women’s History Month in Dance, 2021

Women’s History Month in Dance 1, 2, 3, 4: Mary Wigman. The history of modern dance - and of modernism in dance - tends to be told as if it were an all-American invention. But the American dance critic Edwin Denby wrote in 1944 that “Its <dance modernism’s> first victories through Isadora and Fokine, its boldest ones through Nijinsky and Mary Wigman... - these are facts of history.” I wish that Wigman’s victories were a more evident fact of history today.

The German dancer-choreographer Mary Wigman (1886-1973) is a figure easy to overlook if you see the lineage of American modern dance as going simply from Isadora Duncan via Ruth St Denis and Ted Shawn to Doris Humphrey and Martha Graham and so onward. Yet Graham would not have been Graham were it not for Louis Horst (1884-1964), her lover, her composer, and her advisor in art and aesthetics. In the 1920s, Horst told Graham so much about what Mary Wigman was doing in Europe that in 1930, after watching Wigman dance in her first tour of the United States, Graham burst into tears: she was overcome by relief to find that her own work was not after all just a clone of the Wigman of whom she had been hearing. What this story tells us - I heard it from Bonnie Bird, who studied with Graham in the 1930s and knew Horst - is that Graham became the artist she did because of the idea of Wigman, while forging her own idiom.

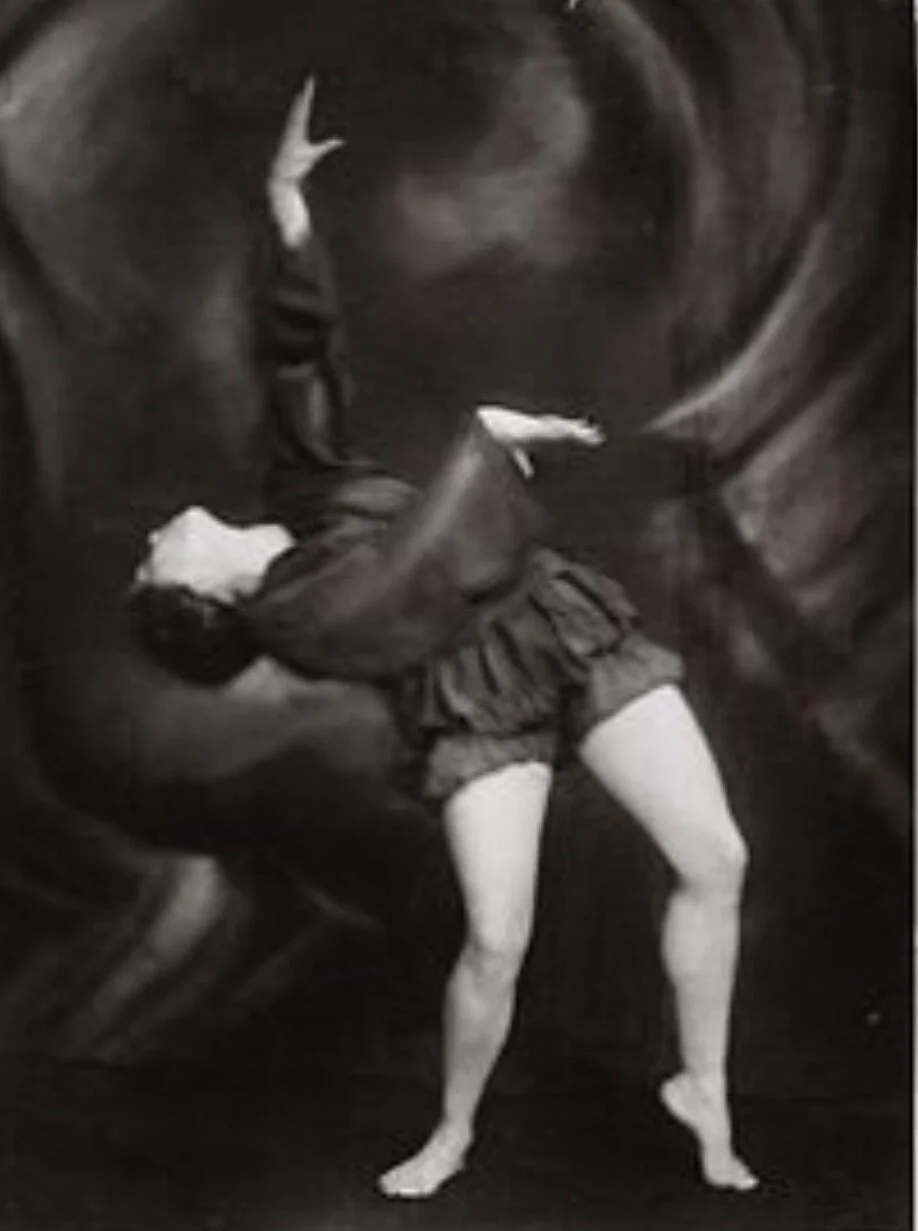

Long before “Lamentation” (1930) and other early Graham solos, Wigman was making solos of harsh, fragmented, and urgent tensions, angles, and rhythms, themselves a radical break away from the essentially Romantic rapture of her contemporary Isadora Duncan. This was a new, uncomfortable, and disconcerting image of womanhood: one capable of darkness, violence, anguish, and protest. The physical tension of the Wigman style, as described by Horst, surely did much to stimulate Graham’s conception of the physical tensions of her own technique. Wigman made her first version of “Witch Dance” (“Hexentanz”) in 1914: YouTube shows her in a 1926 version of it https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=AtLSSuFlJ5c. (Photo 3.) Go from that to Graham’s “Lamentation”: both dances start seated, legs parted. You can feel the connection as well as the difference.

Wigman developed her idiom within the contexts of the eurythmics of Jacques-Emile Dalcroze and the movement analysis and technique of Rudolf von Laban. During the 1920s, she became the standard bearer for Ausdrucktanz, the new German tradition of expressionist dance. Her authority was impressive: Edwin Denby, who danced and collaborated in Germany with her former student Cläre Eckstein in the late 1920s and early 1930s, later recalled a group discussion in 1930 when Wigman rose to speak. As Denby’s friend William Mackay later recalled Denby’s account, “Her standing cut the room with silence, and all around, in odd contortions, a hundred dancers froze ‘like statues, or mimes.’ (‘Whose speaking could be so important now?’ he liked to ask. ‘I know of only two.’” (Mackay does not identify Denby’s two, but it’s likely he meant Graham and Balanchine.)

As so often with German artists, she has acquired a reputation for humourless earnestness, but the diaries she made of her 1930 tour - in the collection of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (Dance Division) - show her often jolly and humorous. In 1933, she wrote “Dance is the unification of expression and function, illumined physicality and inspirited form. Without ecstasy no dance! Without form no dance.”

She was a German patriot. Whereas Laban and Kurt Jooss left Germany before the Second World War, Wigman remained, suffering the fate that many artists did who worked under the Nazi regime. Her style was annexed by the Nazis in their glorification of the Aryan ideal. Still, her schools were closed in 1942, and she was called “decadent”; Goebbels had proclaimed in 1937 that dance should “must be cheerful and show beautiful female bodies and have nothing to do with philosophy”. The pathos of artists who remain in a beloved homeland that becomes oppressive is immense. But Ausdruckstanz has gained a new vitality in recent decades. Today, scholars and dancers continue the work to denazify, clarify, and honour Wigman’s achievement and reputation.

Monday 8 March

14: Mary Wigman, 1922

3. Bonnie Oda Homsey in the early 2000s in Witch Dance II, her recreation or reconstruction of Wigman’s 1926 solo Hexentanz.