Five Conversations with Suzanne Farrell

For Maria Kowroski and Sara Mearns, with thanks.

It’s meaningless to say that one dancer is the greatest ballerina I ever saw, and yet I mean it. In saying that about Suzanne Farrell, I have to add that I never saw Allegra Kent dance Balanchine, that I never saw Margot Fonteyn or Svetlana Beriosova in classical-tutu roles, and that I arrived far too late to see Marie Taglioni or Anna Pavlova or Alicia Markova – though I met Markova a number of times over twenty years. Perhaps Farrell did not change my life as Fonteyn, in her late autumn, and Lynn Seymour, in her high summer, had both done, converting me irrevocably to the passionate observation of ballet. Kyra Nichols’s diversity and purity, over twenty-eight years (1979-2007) of my watching her, were perhaps even more revelatory to me than Farrell’s.

Yet Farrell is the only dancer who could inflect solos with such a dense and bewildering array of ideas that I felt I needed at once to see that performance again to work out what I had seen: ideas about contrasts of scale; play between loss of balance and recovery; the tension between tradition and modernity; the connections between classicism and romanticism; the inflections of impersonal form with personal drama; and the different ways in which a single piece of music can be heard, She would do that, frustratingly, in performances of those ballets she never performed the same way twice. To watch her dance several performances each of Diamonds, Chaconne, Vienna Waltzes, Walpurgisnacht Ballet, and – above all - Mozartiana in quick succession was to have a masterclass in the possibilities of artistic expression. In her mastery of musical architecture, she was the only ballerina I have seen to equal Maria Callas; and, like Callas, she was hauntingly dramatic.

Heroically courageous and effortlessly grand, Farrell sometimes danced as if in infinite space. Some unused to Balanchine style found her cold, but the reverse was true: unafraid to seem vulgar, she thereby transcended vulgarity. Her grands battements had unmatched power (she was hurling thunderbolts), but she would sometimes round them off in (of all ballets) Symphony in C with pelvic bumps. Yet she was often understatement itself: in Apollo, the way she walked in for the pas de deux, touching her fingertip to Apollo’s as if doing nothing special, was sublime. Often she was incandescent.

I was fortunate that I saw her dance often – in New York, London, and Paris – in the years 1979-1983; and occasionally in the years 1985-1988. I have been doubly fortunate that I have had met her a number of times in the years 2007-2019. Three of those occasions were for two features written for the New York Times: those pieces made great impressions on many readers, but, for copyright reasons, I do not repeat here what I quoted from her there. I’m nonetheless aware that Farrell said other things that may be of interest. Today, August 16, 2021, is her seventy-sixth birthday; I use it to set down what I remember and what I recorded of her words.

I.

When Farrell first emerged as the latest of George Balanchine’s teenage prodigies in 1963, she was not known as verbally eloquent. She left New York City Ballet in 1969, still without any reputation as a talker. When she returned to the company in 1975, she was no chatterbox, but she became known for occasional bons mots; and, when in company with writers she respected, for sometimes speaking at length with searching intelligence, originality, and quotability. The prime evidence of this is a long and exceptional interview she gave David Daniel for Ballet Review vol. 7, no 1 (1978-1979); it is reprinted in Robert Gottlieb’s endlessly rewarding anthology Reading Dance (2008). That’s where she is first found to say, among much else, “You can’t rehearse a performance”, a point dear to her heart.

Although I could be said to have met Farrell fleetingly a couple of times in the last century, we were first formally introduced in 2007, when she presented the Dance Division of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts with a copy of a private film of the 1965 dress rehearsal of Balanchine’s three-act Don Quixote. I was in my first year as chief dance critic of the New York Times; I was asked to speak about her dancing; she followed my speech with one of her own. We then sat together, amid the gala audience, to watch the film. It was a treat to hear and see the pleasure she took in the performances of all her colleagues on screen.

At the dinner after the event, we were seated together. I remember only a few of her remarks. Speaking about growing up and learning to dance in Cincinnati, she said “You British really cornered the market in books of ballet photographs! I needed to study ballerinas, and there were so many books with photos of Margot Fonteyn, Beryl Grey, Svetlana Beriosova! I looked at them all. But when occasionally I found photos of Diana Adams and Maria Tallchief and Jacques d’Amboise, those meant more to me: I loved the kind of energy they showed.”

I had watched Farrell dance in New York, London, and Paris between 1979 and 1988, principally dancing Balanchine choreography, from Apollo (1928) to Mozartiana (1981). I, like others, had often been amazed by her unequalled way of reaccentuating some solos differently at each performance, above all in Diamonds (1967), Chaconne (1976), Vienna Waltzes (1977), and Mozartiana (1981). When I, mentioning other Balanchine ballerinas, asked her if she was unique in this respect, she, very simply, said “I don’t know – you must ask them.” She emphasised that no two performances can be the same anyway; that certain solo sequences open up a wide choice of varying opportunities; and that Balanchine had enjoyed her unpredictability.

She did not speak like a diva. It was famous that, in the late 1970s, she had embellished Chaconne with a literally impossible step, the double soutenu turn. (With her long, tapering feet, she had given the illusion of it while actually turning on one foot.) Legend had it that, after the first time she did this, Balanchine, waiting in the wings, had said in astonishment “Suzanne, tonight you do double soutenu turns. Is impossible. How you do?” She, it was said, had teasingly shaken a finger at him while replying “George, if I told you how I do those turns, you’d have every girl in the company doing them in class tomorrow morning” and walked away. After that, she sometimes went back to single soutenu turns but often did doubles and, very occasionally, triples. I asked her about these - but she quietly refused to admit she had ever done (or not done) the step, let alone confirm that conversation with Balanchine; and she made sure I knew that there is no such step as a double soutenu turn.

She spoke a little of her company, the Suzanne Farrell Ballet, and of being a resident artist at the Kennedy Center. Her tone was modest, practical, good-humoured: she did not conceal how few weeks she and her colleagues had to prepare each season.

We also spoke of the critic Arlene Croce and the book on Balanchine ballets that Croce has been preparing for many years. Farrell asked after Croce with respect and interest. When I mentioned that Croce had never studied music, Farrell said “At one time, I wondered if I should study music. I know I’m what’s called a musical dancer, but I left the musical analysis to Mr Balanchine. Still, I wondered if I should know more. But the colleague I consulted advised me that it might spoil the instinct and spontaneity with which I hear music. I think it must be the same for Arlene: we both have a strong sense of what the music is doing, but we’re also working from instinct – which is important.”

At one point, knowing that I had watched many of my early performances in London, Farrell asked if I had attended the 1976 Royal Ballet gala at which she and Peter Martins, as guests, danced the Balanchine Tchaikovsky pas de deux. I explained why I had been unable to be present. But Farrell’s point was not how she herself had danced that night at the Covent Garden opera house; she spoke instead of events leading up to her dancing. She was shown her dressing room, and was told when she could use the stage to rehearse. At one point, all the evening’s dancers were summoned onto the stage together. “A few words were spoken to us. We were from all over the world. We were allowed to assume we all knew who everyone else was, which in most cases we did, but we weren’t properly introduced. I went back to my dressing room to prepare, feeling a little flat. Then there was a knock on the door – and in came Margot Fonteyn. I’d met her a few times over the years, but never known her well. She looked fantastic, and she said, in this wonderfully warm way, ‘I don’t know if anyone has welcomed you to our opera house – but I do so!’ That made such a marvellous difference for me. I remember that now: I’m trying to be the same at the Kennedy Center.”

(The next year, I heard through Cunningham circles that she had indeed welcomed Merce Cunningham, then eighty-nine years old, to the Kennedy Center, visiting his dressing room with the simple greeting “We’re all looking forward to it so much.” Cunningham mentioned his gratitude to colleagues. He died some eight months later.)

II.

I made a rule during my years at the New York Times generally to avoid meeting the dancers and choreographers I wrote about. (A few got through the radar in later years.) Although I attended Farrell’s company’s performances every year at the Kennedy Center - always watching cast changes - she and I never met there. I did meet her another time at the New York Public Library, when she spoke on a panel I was asked to chair on Dance Theatre of Harlem; Frederic Franklin was another speaker. But we had no conversation about her own work or career.

In 2017, however, it was announced that the Suzanne Farrell Ballet would give its final performances there that December. I proposed to the New York Times that this would be an ideal moment for an interview, should Farrell agree. My Times editors approved; so did Farrell. She asked for a preliminary meeting, which we managed when I was visiting Washington in October. I was early. When she arrived, she was strikingly elegant – and immediately funny, in her dry way,

“I do read your pieces, Alastair. And I do believe you do like all the dance you say you like. What I want to know is: How?”

I asked if Washington D.C. was now her home.

“I have two homes: an island in upstate New York – I’ve often taught a dance summer school there - and an apartment here in Washington. I also spend time at the Florida State University - I’m a professor there – but as a visitor, not a resident.”

I do not include here parts of what she said on that occasion, because they were so beautifully formulated that I used them in the published interview two months later. I did ask her about this striking command of words she showed.

“I had to learn how to speak. When I was a dancer, I didn’t need to speak most of the time. And Balanchine much of the time was not verbal: he showed movement – fantastically. He could be witty, he could use words very memorably, but they weren’t his first form of communication with his dancers. Well, I was fine with the non-verbal side. Using words I had to learn.”

Her conversation turned to Balanchine frequently, relaxedly, seamlessly. (“Balanchine is my life, my destiny.”) “When he was teaching class, he was always saying ‘Fifth position, fifth position,’ every day. As a young dancer, I said to him once, ‘You’re always saying “Fifth position.”’ He said ‘That’s because I so rarely see it.’ That made me decide to give him the fifth position he wanted.

“People would be surprised to know the order in which Balanchine choreographed a ballet. With Diamonds, the last thing was our entrance for the pas de deux. We knew the pas de deux itself, but then he took us by surprise with that entrance. There’s a long passage of music with nobody onstage; then the man and woman arrive at opposite corners, standing and facing each other across the whole of that big stage.”

Balanchine made successive changes to Serenade during her era: he opened cuts in the Tema Russo (Russian Dance) in 1966; in 1976, he loosened the three lead women’s hair in the Elegy. That loosening of the hair was a major topic of controversy when I first watched New York City Ballet in 1979; it remains controversial in some circles to this day. I asked Farrell about this. Farrell: “The hair is down only in the final Elegy, which begins with the entrance of the Dark Angel. Did you ever see an angel with her hair up? In paintings, angels have hair flowing.”

“When Balanchine was making Vienna Waltzes, I kept wondering who my partner would be. I kept seeing my partners go by with someone else – Peter (Martins) was dancing ‘Gold and Silver’ with Kay (Mazzo), for example. But then Mr B. said to me ‘You’re not going to have a partner, you’re going to dance alone.’ There is a shadowy partner for me, who comes and goes – and that was Jean-Pierre Bonnefoux, whom I’d almost never danced with. (Then Jean-Pierre was injured, and at short notice we brought in Jorge Donn, whom I certainly had danced with, in the Béjart company, but who wasn’t a member of City Ballet.)”

She also spoke about her teaching, in which she enjoyed challenging her dancers with novel ideas. “I ask my students to visit the zoo, and I ask them to choose an animal and imagine themselves moving like that. (Not a swan! – that’s been used in dance too often.)

“The next day, I take numbers, and I ask them to arrange, say, four counts of five - in the style of the animal or bird they chose. The animal task helps their imaginations - but the rhythmic requirement helps them to think structurally. You need to be able to feel a rhythmic structure in ballet.”

“I’ve been teaching an ‘Adults Discovering Ballet’ course for several years here at the Kennedy Center. These adults really want to move, and some of them don’t have any experience in ballet. That’s fine – it’s exciting, to see them really go for it – but it means I add things we didn’t do for Balanchine. In a Balanchine class, there was no stretching at the barre, no raising of the leg onto the barre. You did one range of exercises at the barre, then you went to the center. With adults new to ballet, however, it’s often a good idea to give them those stretching exercises.”

Again, I hope lightly, I mentioned her double soutenu turns to her, but she brushed them away without ever confirming that she had danced the step I meant. Instead, she spoke of the importance of spontaneity, of not leading people to expect some special technical effect at each performance. “Only once did I say I was going to do a particular virtuoso step. You know that New York City Ballet used to turn the New Year’s Eve Nutcracker into quite a party, with the Snowflakes throwing their wands into the wings and so on. One year, everyone was preparing various changes of costume and makeup. I was going to dance the Sugarplum, so I said ‘Okay, I’ll do four pirouettes.’ But then I had to deliver four pirouettes! Well, I did them, but that taught me not to announce - or plan - in advance.” (She was referring to the sequence in the Sugarplum adagio when the ballerina usually performs a pair of double pirouettes from fourth position: evidently Farrell did deliver quadruples that night, and added them in the pas de deux’s coda too. Eyewitnesses among her co-performers also say – Farrell did not - that she also blacked out her teeth that night, cracking up members of the cast by occasionally flashing an apparently toothless smile.)

“Staging Apollo the first time was an important exercise for me. I was working on the passages with one man and three women, and at first it kept feeling as if there was one woman too many – me. I had to learn how to be part of the rehearsal but distance myself from the dance I knew so well.”

How did she feel, I asked, about the company she was assembling for the farewell season? Many of them had been returning season after season. “It’s a happy company; I have a very good ballet mistress, who used to dance in it – when she retired as a dancer, I knew I wanted her to stay with us. Our rehearsal space is limited, and often we’re all working in one big studio, she with the corps over there, me with the principals over here. That has its advantages: we all have a strong sense of a single objective, so it’s like working on a ballet when it’s new.”

She wants spontaneity in her dancers. Is this something she looks for in auditions? “I set some tricky combinations in auditions. It’s good to find out how they cope with challenges. Sometimes people have returned because, though they failed the first year, now, a year later, they feel ready for it now. I give them information in class, to show them how to learn. You have to have your eyes and your ears ready to learn.

“Some big companies now get to rehearse ballets with the corps in one room, the soloists in another, and the principals in a third – and it looks like that when you see the performance. I have to have understudies, but I’m also giving them dancing to do at some performances. Everyone gets to be used – we’re not a large troupe. That’s how it was in City Ballet under Balanchine: he found a use for everyone. And he choreographed those ballets so that they’re interesting for the smallest corps roles as well as for the leads.

“I remember standing at the rosin box preparing for a performance, when a young dancer came up. As she was putting rosin on her shoes, she said ‘I’m only on for one entrance.’ And I knew I was doing the big lead role. But I said ‘Believe me, your role counts, and it’s not boring.’

“Balanchine’s Mozartiana is the ballet I teach most. With one variation I say, ‘Do you hear that Whirr in the music?” Well, some dancers just don’t hear that Whirr. You can’t force them to hear the music the same way you do. But you can help them listen more carefully, make them hear the different options in the music. You help them to respond to what they hear, not what you hear.

“Balanchine didn’t arrive with a fixed idea of how everything should be. Look at the film of the first performance of the Mozartiana Minuet (1981): those four girls are all doing slightly different things! Because each is doing what Mr. B. told them, it looks really good – the energy and intention are so sure. But when you’re teaching that Minuet, you have to work out precisely which point he was trying to give them in the first place, exactly what he was asking them all to do. In those situations, I always go back to the music. What did he hear that made him ask those steps in that sequence?”

We spoke of holding balances in Balanchine choreography. Almost always, Farrell confirmed, they should not be static. Movement must continue, “even if it’s just with the eyes.”

In her dance prime, Farrell had been known to object to dancers who used their eyes too much. In the twenty-first century, however, she found herself asking dancers to use their eyes much more, above all to open up space and not to address the area straight ahead (in the studio, the area taken by the mirror).

Did Balanchine teach her about the use of the eyes? “Not eyes but épaulement.”

III.

The Suzanne Farrell Ballet was never a year-round enterprise. Only in some early seasons did its dancers include luminaries from leading companies. Mainly, it danced Balanchine. Several seasons included revivals of rare Balanchine ballets, under the title of Balanchine Preservation Initiative (although on one occasion that included Balanchine’s 1972 Danses Concertantes, a wonderfully witty ballet then in good condition as danced at New York City Ballet and not in need of preservation). Many central Balanchine classics came up as if new. I especially return in memory to her 2010 staging of Balanchine’s Apollo, by far the freshest I’ve seen since Balanchine’s death. The December 8, 2019, performance included Balanchine’s well-known Serenade (1934), George Jackson, a veteran Washington critic, emailed all his local dance contacts with these words: “Tonight's Serenade was the greatest I have ever seen…. Its phrasing has changed my idea of ‘romantic’ and ‘classic; this was a new beast.”

Farrell’s final season was named Forever Balanchine. I watched its December 7-9 performances, then returned to Washington on December 12. As in October, she, now seventy-two, was dressed with quiet but modern elegance.

She often referred to her siblings and their offspring (including a great-nephew aged six, whose interest in each ballet she takes seriously) and to growing up in Cincinnati, Ohio. Mainly, however, she speaks to me of Balanchine. (Sometimes he was “Mr B.” or “Mr Balanchine,” as he remained for many others, very occasionally “George”.) “How could it be that this girl from a small town came to dance all these roles and have this career? I embrace all opportunities. You just have to be prepared.”

She referred to the famous period of 1969-1975 when she danced away from New York City Ballet. Mainly she danced mainly for Maurice Béjart’s Ballet of the 20th Century. “Everyone said I was wasted by dancing those years in Europe. I didn’t feel wasted. I live in the now, I always have. And I would always do my Balanchine barre. Had I not done so, I would have been unable to catch up, on my return.”

Ms. Farrell the ballerina was the ultimate exemplar of off-balance dancing. Croce - whose writing about Farrell was itself superlative - once wrote “She cannot fall.” When I quoted that line to Farrell, however, Farrell exclaimed “Oh, I fell once - in Diamonds! That was with Jacques d’Amboise - a great partner. Tutu ballets can be so hard in terms of partnering, and I didn’t hold back.

“I knew a dancer who had a great fear of falling onstage, but I didn’t. You have to fall off balance the whole time; that’s part of the essence of dancing.”

Her Forever Balanchine program included Meditation, the first work he ever made for her. Farrell: “In 1965, Balanchine gave me the rights to that. He didn’t want anyone else to dance it. I respected his wishes while he was alive and while I was dancing. But ten years after I retired, 1999, when I began to set up a Suzanne Farrell season here at the Kennedy Center, I did revive it. What good is a Balanchine ballet if it’s not seen any more?

“There are two moments in Meditation I found hard. The first was the entry, with arms open wide; I kept wobbling. Balanchine could see I found that problematic, so he moved onto the next section and left me to work on that. And I tell my dancers that now (we had three casts of it this weekend), so that they know. I also tell them that there’s another step later in Meditation that I always found hard – but I don’t tell them what it is!”

I told Farrell that my companion at one Kennedy Center performance had seen Meditation as the story of his recent short-lived second marriage. He felt the woman (like his new ex-wife) is all self-contradictions, saying “I am your dream - I need you - you cannot have me - I inspire you - keep your distance - you are everything to me - farewell forever!”

Farrell laughed at that. “I couldn’t have thought that when Balanchine made it for me – I’d never been in love. I only knew about love what I’d seen in the movies – and Swan Lake. I did have a very Hollywood idea of love.”

Her December program included Tzigane, the first piece Balanchine made for her when she returned to City Ballet in 1975. Farrell: “Tzigane was made for the Ravel Festival. Balanchine made Tzigane for me one week before its premiere. I had very little information. But Balanchine came round to my house and played me the music – I think it was a Jascha Heifetz recording, quite scratchy.”

Much of what she said to me that day is in the New York Times piece published on December 19, 2017 (“After the Curtain Falls: Talking to Suzanne Farrell, Artist and Muse”); I do not copy that here. But here is one further example of how she spoke of herself with amusement.

“Sometimes I call myself ‘Miss Farrell.’ When I was first staging Mozartiana, I said to myself ‘Miss Farrell, maybe you should watch the video and see what you did.’ But when I looked, I saw that, in that performance, I wasn’t doing things the way I know I liked to do them. Even I wouldn’t be me!”

IV.

The following year, I convened a New York Public Library seminar on Balanchine’s Apollo. Farrell could not attend, but agreed to speak to me by telephone. I had seen her dance Terpsichore on both sides of the Atlantic, with two different male dancers as Apollo, in 1980 and 1982, in Balanchine’s final version of the ballet, without prologue or staircase finale. I had also seen her own 2010 production of the complete ballet, in which both Prologue and final apotheosis ascent were restored (the 1957-1978 version of the ballet).

When I said I would send a list of Apollo questions by email, she told a mutual friend “I’ll answer maybe two!” Nonetheless I sent thirty. She began the phone conversation by saying “These are really good questions, Alastair. They’re about what matters in Apollo. But I’m not going to answer any of them!”

Though she’s good with words, she’s also wary of them. We spoke for an hour, but often on non-Apollo matters. Nonetheless she did speak on a few points. I’d also say that, by the end, she answered quite a number of my questions.

Had Balanchine coached her as Terpsichore, a role she danced for perhaps twenty years?

Farrell: “I didn’t really learn Apollo. I was thrown on in it. I’d been a little handmaiden in the Prologue. I knew my part in the birth scene; I returned at the end. I stayed around in between.

“Then I was thrown on at the last minute. I said ‘I don’t think I’m ready.’ He said ‘You let me be the judge.’

“I also think that, by then, his vision was of a tall Apollo. He may have tried smaller Apollos earlier on, and indeed he did briefly later. But when he came to Jacques, it was thirty years after the premiere.”

I asked about imagery. Balanchine, when coaching male dancers as Apollo, amazed them by providing a greater supply of verbal imagery than for any other ballet. Of the Balanchine women dancers to whom I had spoken, however, only Suki Schorer (dancing Calliope) remembers any specific imagery he gave her.

Farrell: “Imagery. Balanchine never referred me to any Greek statue; but I do think a sense of Greek statues does inform you as you look for how to be in this ballet. Half of the Greek statues don’t have their appendages, and yet they tell us so much of how to stand and carry ourselves. I tell my dancers, ‘Find how to be comfortable like a Greek statue.’

“The libretto is by Stravinsky. Everything is then blocked out by Balanchine. Apollo was important to him.”

I asked about the particular use of shuffling on flat feet that recurs at several points in Apollo.

Farrell: “The shuffling on flat feet: I find it vulnerable.

“You have to give yourself to both the classicism and the unclassicism of the choreography. To me, those two sides are the style of Apollo: it’s both.”

Lynn Seymour, who learnt Calliope from Balanchine in Germany in the 1960s, had been my own first Terpsichore, in 1975. In a 2014 interview, she had told me that he - lightly - told her that all three muses were versions of himself as a failed artist. I ran this past Farrell.

Farrell: “What Lynn remembers Mr B. saying: that’s interesting. But I don’t think they’re failures. I know Apollo shows his shoulder to one muse and turns his face from another. You have to think about what that means: but I don’t think they’re failures.”

I mentioned the different levels or layers to the music in Calliope’s variation, with bass notes as this muse seems to reach into her own guts.

Farrell: “With Calliope’s variation, that gesture to her torso – she’s going to her heart: her poetry is coming from her heart.”

I asked about Terpsichore’s variation. Farrell: “I may have learnt the variation from Jacques (d’Amboise): he showed me so many things. I watched Diana <Adams>: she was very important to me. There’s one jazzy step in her variation: it’s syncopated. It’s only awkward if you don’t give yourself fully to it. You have to give yourself to the choreography: that classicism and that unclassicism.

“When we danced it with Stravinsky in Hamburg in 1966, Stravinsky took my variation very fast. I even fell, trying to do the steps at that tempo. I asked Mr. Balanchine, ‘Was it always that fast?’ He said ‘No.’ So that’s why, in that German TV film with Stravinsky conducting, I only do that step – relevé in arabesque with arms en couronne – twice, not three times! I’d hate that version to be passed down as the right one.”

I mentioned the simplicity with which she walked in for the pas de deux to touch her fingertip to Apollo’s. (The image is taken from Michelangelo’s God and Adam in the Sistine Chapel.) Farrell: “The entry for the pas de deux: she makes her entrance to one chord in the music. So that Sistine Ceiling moment is just a transition: you touch fingers with Apollo, but the music builds and you have then to turn away and gesture up and out. That’s such a chord building. The fibres of your body are affected. This is the beginning of their union. Then their fate is sealed.”

When Apollo makes his final return to the stage, the three muses watch him in a wonderfully 1920s way, keeping their legs parallel and their knees bent. Farrell; “That pose for the three muses as Apollo returns, with one leg crossed over the other – that was a very contemporary pose when Apollo was new in 1928. It’s not normal nowadays. But you have to make it normal.”

The muses and Apollo then dance together in a finale that is by turns playful and energetic. They chug rhythmically together, and then they become wonderfully multi-directional, pivoting together to face north, south, west, east, and so on. Farrell: “When it comes to the finale, the whole thing is building. Apollo has grown. We’ve taught him all he knows. He’s grown. He’s absorbed all the muses have taught; they honour him. They are exalted, because they succeeded.”

Farrell had performed Terpsichore for Balanchine in the 1960s, dancing it in several countries. When she returned to New York City Ballet in 1975, Apollo was out of repertory until 1979, when he cut the Prologue, removed the staircase, and changed the ending. Farrell returned to the role of Terpsichore in 1980.

“The birth scene: I think other circumstances led him to cut it. I did ask him about it; he said nothing. I knew he could do whatever he wanted to his ballets, but he rarely altered the music. It was puzzling. He was so loyal to the music.”

V.

Farrell’s career has featured two prolonged absences from New York City Ballet; the 1969-1975 one and then a much longer one, for twenty-six years beginning in 1993. She returned in April 2019, to coach the two leading couples in Balanchine’s Diamonds (1967), in the same large cube-shaped studio where Balanchine had created it, with herself in the ballerina role. Her visit to New York was dual-purpose: she was also teaching a Balanchine seminar at Steps. Although few knew this in April 2019, Farrell was at the time preparing to leave the East Coast; she subsequently moved to Arizona, where she has good friends and where the warm, dry weather suits her health.

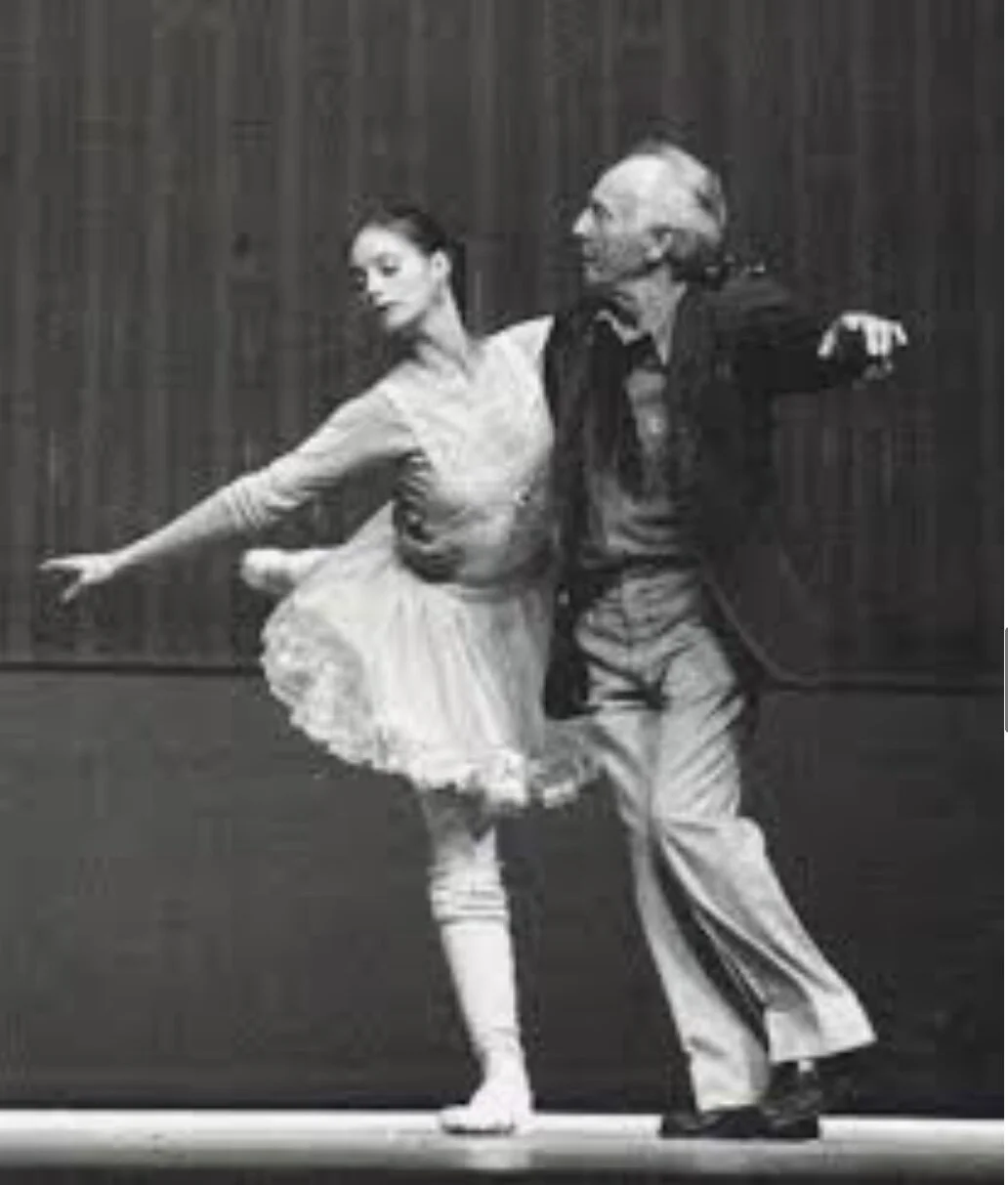

She worked for two hours on Wednesday 17 April with Sara Mearns and Russell Janzen, then for two hours on Thursday 18 with Maria Kowroski and Tyler Angle. I was privileged to be invited by City Ballet to observe the Friday 19 session, when she took each couple through their roles. Watching the rehearsal were Jonathan Stafford and Wendy Whelan, City Ballet’s artistic director and associate artistic director since February that year; and Andrew Litton, the company’s music director since 2015. Kathleen Tracey, the City Ballet master charged with supervising Diamonds, was present throughout, taking notes. Stafford, in particular, had begun a policy of bringing in Balanchine and Robbins alumni to coach; he had been trying for months to bring in Farrell. I had never attended any rehearsal there, and had seldom been backstage in the New York State Theater.

My account of that afternoon was published in the New York Times on April 23 that year (“A Balanchine Muse and Star Returns to New York City Ballet”). It was a big hit with readers; I don’t repeat here what I wrote there. I do, however, add some further notes.

The mood for those two hours (and more – Farrell overran) was full of laughter, deep emotion, close analysis, and liberating commentary. All four dancers were happy to receive any correction, because Farrell, on the two preceding days, had established an exceptional mood of intimacy and intelligent inquiry with them. Known sometimes for cutting a high-fashion figure on other occasions, Farrell was dressed in ordinary clothes, but her outfit included a shocking-pink top. When Angle arrived in a T-shirt of the same colour, he laughed as he drew everyone’s attention to the coincidence. Farrell, after saying how seldom she wore that colour, remarked “We’re in synch.”

She had helped Kowroski and Mearns by telling them aspects of the ballet’s creation. In its second movement, ballerina and male dancer approach each other in a zigzag route from opposite corners; but Balanchine added this entrance later, as if at first unsure how to handle that music. Rehearsing Mearns, Farrell drew attention to the use of the raised elbow (“We’re developing a motif here”); rehearsing Kowroski at almost the same moment, Farrell simply said “You reveal yourself.”

More than once to Mearns and Janzen, she advised “It’s not Swan Lake, remember?” (The man should not always follow the woman here; sometimes the woman summons him with her eyes. And no “wing-beat” arms.) After working on a revised phrasing in one passage of the pas de deux, Angle exclaimed in satisfaction, “What alchemy! That works so well.”

She also drew the dancers’ attention to the ways in which Diamonds, the closing ballet of Balanchine’s pure-dance trilogy, differed from the preceding Emeralds and Rubies. “Emeralds has a different rhythm in the walk. That’s why emeralds have a different colour.” When Angle stretched an arm one way, Farrell remarked “The arm is down like that in Rubies. For Diamonds, stretch it higher.” (She also changed its direction to a diagonal. She added “It’s not a pose! You’re just using your arm to get momentum. If it were a pose, you’d have to start all over again.”)

Diamonds is to four movements from Tchaikovsky’s five-movement Symphony no 3. Though Farrell took the dancers through the precise counts for their movements, she often sang those counts to the music’s melody. One particular series of low-sweeping lifts, set to counts of six, became newly fascinating as she showed how Balanchine brought a different rhythmic accent to each one.

A mood of wry humor kept resurfacing. Once, Kowroski asked “Was that okay?” Farrell replied “I didn’t wrinkle my nose.”

They moved on to the ballet’s finale. Angle, the most extrovert person in the room, made everyone laugh as he asked Farrell “What was the most offensive thing about that?” Ms. Farrell calmly established that he had been doing a step that was never in the original choreography.

Sometimes she said “That was nice,” at other times “I didn’t think that looked very pretty.” Further on, she emphasized, “We’re substantiating everything we established in the pas de deux! We’re recapturing it.” But the interpreters should avoid overstatement: “You can’t out-Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky.”

She spoke to the two ballerinas if she were inside their bodies. Kowroski and Mearns, speaking to me immediately afterward, were both wide-eyed with wonder and gratitude. Kowroski told me she had left after the previous day’s rehearsal “in a dream”; Ms. Mearns had found the experience “unreal.”

Both, as they went home and absorbed what they had learned, had found themselves in tears; and both recalled multiple revelations. Mearns said “It’s freed me more. I feel I can be more normal, more human with the person I’m dancing with, less stuck-up in this tutu role..… Everything she said made such sense. She’s shown me little moments when I should stop, finding pauses within the phrase that I never knew were there. And she said ‘Don’t go to the audience. They’ll come to you by the end.’”

Kowroski remarked, “I was surprised by how nurturing she was. She’s so much on our side, almost maternal, very comforting. To know that we could try new things was so wonderful – it didn’t matter if I got things wrong! I was so happy to try things out for her…. It made so much difference to learn that the ballerina here is not the queen – that she is vulnerable.”

Farrell seemed the coolest person in the room. After the rehearsal ended, she spent time talking extensively with Kathleen (Katie) Tracey, the ballet master supervising Diamonds (and who took copious notes), pleasantly discussing fine points.

To me, she then remarked, “Most of the things were timing things. I’ve said to them ‘You don’t have to be beholden to counts; but you must sense the structure and the phrasing. You can hear the music different ways; I just want them to show me how they’re hearing it.”

I mentioned Kowroski’s fascination with learning that the ballerina enters with vulnerability. “Yes,” said Farrell, “You <the ballerina> are capable of being changed.”

Litton, the company’s music director, watched most of the rehearsal. He told Farrell in mid-rehearsal how much he was learning. To me, he later remarked “It was moving on so many levels.”

All this took place in City Ballet’s home, the David H. Koch Theater, at Lincoln Center. It was originally named the New York State Theater; she had danced in its opening performance in 1964. I left it with her and with two of her most trusted colleagues from the Suzanne Farrell Ballet. Turning to me, she made a remark both wistful and paradoxical: “I’m staying at the Beacon Hotel, which is near Steps. It’s directly opposite the Ansonia, where I stayed with my mother and sister on my first trip to the city. I feel as if I’ve never left New York – and I feel as if I’ve never lived in New York.”

@Alastair Macaulay 2021