Pinter’s Women

by Alastair Macaulay - Times Literary Supplement, April 14, 2006

This was the opening lecture of a March 2006 symposium in Turin, Pinter: Passion, Poetry and Politics, marking the playwright’s acceptance of the Premio Europa per il Teatro. When Antonia Fraser, Pinter’s wife, heard that I would be giving a lecture with this title, she emailed me: “I expect to learn a great deal! Love, Pinter’s Woman.” When the lecture was published in the TLS, Pinter telephoned me to say “I read what’s written about me in the Pinter Review and most newspapers; and I can take them or leave them. But you’re really in it.” He encouraged many of his closest friends to read it.

Last year, Harold Pinter let it be known he was unlikely to write any more plays. He said he would devote the remainder of his artistic energies to poetry. I was curious to know if all his recent poetry was about war, cancer, death. Next time I saw him, I asked him. Without skipping a beat, he recited the following:

“Breasts, bottom, thighs, the whole palaver,

I raise my hat to my uncensored sister

Who shone the light of love on those about her

Who lusted longest on her black suspender.”<1>

I remember laughing in glee. But I later realised that he’d quoted it because it had just been published in The Spectator. Actually, according to the latest edition of his anthology Various Voices, he’d written it in 1973. So he hadn’t quite answered my question. Even so, it reminds us that his thoughts turn readily to women and, in part, to their sexual allure even at a time when, to be honest, he knows that the end of creativity and the end of life may be near.[2]

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

As far as I know, Pinter does not believe in God. Some of his characters seem to, but I pay a different attention when Pinter himself refers to the Almighty or the Creator. He does so in a 1996 interview when the subject turns to women:

“There’s a terrible two-line poem by Kingsley Amis, in which he says “Women are so much nicer than men/ No wonder we like them.” My wife considers these lines to be very patronizing and they certainly are, I agree. But nevertheless I just believe that God was in much better trim when He created woman.”

In fact, Pinter misquotes Amis here, from a poem that actually consists of several stanzas. But leaving that aside, what does he mean by that? There’s no one pattern to the women in Harold Pinter’s work. They come from upper class, middle class, lower class. Some are strong, some weak, some both. Some have children, some parents, some sisters, some husbands, and some seem to have arrived out of the blue from nowhere. Some have lives that are circumscribed by men, others demonstrate various degrees of independence from men. Some of them, not all, are intensely sexual beings, but their sexuality isn’t all addressed to the male sex. Some make men suffer, some suffer because of men. What’s more, he doesn’t need women in his plays. In some of his finest - The Dumb Waiter (1957), The Caretaker (1960), No Man’s Land (1975) – there are no women at all.

Much of his drama is to do with power politics; and a point that invariably emerges is that those who try to exert control over others are in fact doing so from some kind of weakness. Another point that arises is that no one in Pinter can be fully possessed or fully controlled by anyone else. And the reason for this is that no one in Pinter can be fully known. Humans in Pinter are inscrutable, ergo unpossessable, ergo uncontrollable.

We feel this best when we sense the space and time he places around each character. Time, of course: those pauses, those silences. But space, too. He told me once that he thinks choreographically in planning his plays. Well, even the weakest and most vulnerable characters in Pinter tend to have space about them most of the time. Time and space are part of the inviolable mystery of each person on his stage.

And he places more space and more time around certain women.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The other chief device whereby a character in Pinter will show his or her freedom from another is the non-sequitur. One of the best examples comes in Act Two of The Homecoming (1965). The men have been talking of this and that, and Ruth has been silent for two pages. Finally, they’re talking about chopping up a table (as men do). Then Ruth speaks:

Ruth: Don’t be too sure though. You’ve forgotten something. Look at me. I… move my leg. That’s all it is. But I wear… underwear… which moves with me… it… captures your attention. Perhaps you misinterpret. The action is simple. It’s a leg… moving. My lips move. Why don’t you restrict… your observations to that? Perhaps the fact that they move is more significant…. than the words which come through them. You must bear that… possibility… in mind.

Silence.

I was born quite near here.

Pause.

Then… six years ago, I went to America.

Pause.

It’s all rock. And sand. It stretches… so far… everywhere you look. And there’s lots of insects there.

Pause.

And there’s lots of insects there.

And with that speech she changes the play. She states, for one thing, that this is her homecoming too. She says, in effect: “Watch what I do – actions speak louder than words. And pay attention to the things that are implicit without being seen or heard.” She asserts her sexual allure. But she also acquires a certain pathos. She went to America, but it isn’t home, it’s arid, and it has these damned insects.

She goes on from there to discard her own husband, to become instead a lover, wife, mother to the other men in his family, and probably to many other men to come. She plays the men’s game, but on her own terms.

Isn’t she the necessary descendant of Nora at the end of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House? Like Nora, she claims that she has a duty to herself that is more important than her duty as a wife and mother. Unlike Nora, it is Ruth’s husband who, at the end, walks out and closes the front door. Ruth’s homecoming is, for her husband and us, dismaying. But it’s among the most breathtaking acts of independence in Pinter.

Let’s not kid ourselves. In giving voice to individual female characters, he’s not just saying, This is what women are like and what men cannot be; this is what I desire or admire or fear or distrust in women. He is also giving voice to one aspect of himself.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Memorable as The Lover (1962), The Homecoming, and other early Pinter plays (and their women) are, the later plays are more audacious and difficult plays – and in the best of them he created women who achieve a much stranger, more painful kind of independence. To my mind, the greatest Pinter starts around 1968. One of the distinctions between the earlier and later phases of his work is to do with a new largeness of spirit, and a new ability to articulate feeling and experience, which he locates principally in certain women.

In early Pinter, the main drama is to do with what is being left unsaid, or what neither men nor women know how to say. (Of course, that’s true of much later Pinter too, even where the characters are clever, as in the 1978 Betrayal 1978.) Looking at early Pinter, I think I find just one character who’s an exception to this rule; and she comes from as early as 1956. It’s a poem, called The Error of Alarm, and the subtitle is “A Woman Speaks”. Here are the final four of its five stanzas:

If his substance tautens

I am the loss of his blood.

If my thighs approve him

I am the sum of his dread.

If my eyes cajole him

That is the bargain made.

If my mouth allays him

I am his proper bride.

If my hands forestall him

He is deaf to my care.

If I own to enjoy him

The bargain’s bare.

The fault of alarm

He does not share.

I die the dear ritual

And he is my bier.

It’s an enigmatic poem, but “her” tone is open, honest, because she so well understands the tension, the ambiguity, of male-female relations. And it’s a striking early example of Pinter disclosing the female voice within himself.

You can’t think about Pinter long without feeling that, within this out-and-out modernist, there is a powerful Romantic at work. When it comes to gender, he’s a Romantic dualist. There isn’t much androgyny in Pinter. Men are men, women women, and the distinction between the two is already one basis for drama, even though he expresses part of himself in some or all of his women. As with heterosexual male artists from Wagner to Balanchine, he has needed to use the feminine principle to give voice to things he will not ascribe to male characters. If I understood Jung better, I think I would analyse some of his supreme male-female dialectic as the dialogue of animus and anima.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Pinter first fully enunciated these separate principles in his 1968 play Landscape, and I think he never wrote anything so perfect before or since. Duff and Beth sit at a table and talk, but they seem not to hear each other. The differences between them are crucial. He talks to her and about her, and is frustrated that she never hears. She, by contrast, never looks at him. Yet it’s possible that at some level she does hear: every time she speaks, she seems to be changing the subject, to be eluding him. The main ambiguity of the play is whether she is talking about him or about some other man. Gradually it emerges that she has passed through some shock and has blocked herself off from present-tense reality. But the beauty of the play is that she has retreated to a realm of memory; of sensitivity, and love.

At its end, Duff describes a moment, possibly the moment when she was first traumatized (“You stood in the hall and banged the gong”). He recalls what he’d like to have done to her, with very definite ideas of what men and women are.

Duff: I thought you would come to me, I thought you would come into my arms and kiss me, even… offer yourself to me. I would have had you in front of the dog, like a man, in the hall, on the stone, banging the gong, mind you don’t get the scissors up your arse, or the thimble, don’t worry, I’ll throw them for the dog to chase, the thimble will keep the dog happy, he’ll play with it with his paws, you’ll plead with me like a woman...

But Beth’s memories are of a quite different moment; and she closes the play like this:

Beth: He lay above me and looks down at me. He supported my shoulder.

Pause.

So tender his touch on my neck. So softly his kiss on my cheek.

Pause.

My hand on his rib.

Pause.

So sweetly the sand over me. Tiny the sand on my skin.

Pause.

So silent the sky in my eyes. Gently the sound of the tide.

Pause.

Oh my true love I said.

Landscape is a modernist version of a Romantic mad scene: she is singing of love and bliss and loveliness; everyone else, in a realm of blunt prose, knows she’s out of her wits. Yet she is happier, freer, and, in an important sense, larger, even stronger than they (or we) are. The unbearable poignancy of the play is its two opposite implications: one, that she is indeed talking about Duff; the other, that it was he who drove her into this condition.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

One way or another, Pinter’s women often elude their men. They remind me of a late-Romantic heroine, Mélisande. In Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas et Mélisande, and in Debussy’s opera, in the opening scene, her future husband Golaud, finding her amid a forest, starts to interrogate her. At one point, he says:

Golaud: Oh! Vous etes belle! Quel age avez vous?

And she replies with a non-sequitur that sounds echt Pinter:

Mélisande: Je commence à avoir froid.

What age are you? - I’m beginning to feel cold. To talk of “cold” is Mélisande’s way of eluding his grasp, and also to put the dampers on his possessiveness. Kate does it in Old Times (1971) to Deeley and Anna. They’re talking about her smile, the smile she had years ago and that she still has, and she chimes in by saying “This coffee’s cold.” Anna apologises straightaway; and the conversation changes. (This isn’t the only time that “cold” occurs in Pinter to put a chill on people who are becoming possessive.) Kate takes charge of the end of Old Times by the opposite of a non-sequitur. She turns to Anna, and says: “I remember you dead.”Kate pronounces Anna dead at some length, consigns her to the past, and – still addressing Anna – she refers to the memory of a man who is almost certainly Deeley. Devastatingly, she says:

He suggested a wedding and a change of environment.

Slight pause.

Neither mattered.

Kate asserts her complete freedom from the others, and remains immobile for the remainder of the play, and, by so doing, she casts them into tragedy. When you first take in Old Times, you feel, at first, liberated with Kate: her act of independence is as breathtaking as Ruth’s was in The Homecoming, and it seems less dismaying because she really does achieve liberty. The more one see this play, however, the more its ending touches on tragedy. Pinter closes it with seven different wordless tableaux: Kate never moves, but Anna and Deeley move around her from one position to another, positions that re-enact the past – that are the past, the past in which they are stuck forever.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I’ve mentioned the Romantic mad scene, and Pinter comes close to it in two later plays: A Kind of Alaska (1982) and Ashes to Ashes (1996). The heroines of these two plays are both set apart psychologically, like Beth in Landscape. In A Kind of Alaska, Deborah is emerging from a terrible ordeal, twenty-nine years of apparent sleep, and the play’s climax is her delivery of an astounding monologue. As it begins, she re-lives the waking claustrophobia of her supposed sleep:

Deborah: Yes, I think they’re closing in. They’re closing in. They’re closing the walls in. Yes.

Let me out. Stop it. Let me out. Stop it. Stop it. Stop it. Shutting the walls down on me. Shutting them down on me. So tight, so tight. Something panting, something panting.

She moves through various stages of feeling and awareness before finally reaching these final two paragraphs:

Deborah: You say I have been asleep. You say I am now awake. You say I have not awoken from the dead. You say I was not dreaming then and am not dreaming now. You say I have always been alive and am alive now. You say I am a woman.

She looks at Deborah, then back to Hornby.

She is now a widow. She doesn’t go to her ballet classes any more. Mummy and Daddy and Estelle are on a world cruise. They’ve stopped off in Bangkok. It’ll be my birthday soon. I think I have the matter in proportion.

Thank you.

Deborah is not a victim of other human beings, but of an accidental medical condition. She comes to terms with it; in the end - and this is what makes her a Pinter heroine - she is not dependent on those people who have looked after her for nearly thirty years. She takes control and responsibility for her life, and regains her own space. She has been through something like tragedy, she bears witness to it, and she achieves some painful kind of grim victory. But it is also a kind of shrinkage. Like anyone who has been through a huge emotional experience, to return to the blunt facts of everyday reality does not bring with it unequivocal relief: it brings, too, a sense of loss.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Ashes to Ashes is not a flawless play. Even so, I am tempted to call it Pinter’s greatest. In Landscape, the heroine is locked into an altered psychological state; in A Kind of Alaska, she is painfully emerging from one; in Ashes to Ashes, she keeps slipping back into one. She, Rebecca, keeps expressing what she feels are memories, and what he, Devlin, sometimes insists are delusions.

Devlin is the most ambiguous man in all of Pinter. The conversations between him and Rebecca fall into several patterns. At first, they feel very much like Freudian analysis: she is recounting memories or dreams, and he is trying to pin these accounts down, to understand them. But soon he steers the conversation towards the pattern of Socratic logical dialectic, trying to bring rational explanation and argument – traditional male strengths - to bear upon what she says. And through all of this, she eludes him with lateral thinking of her own, or with what we might call dream logic. Here is one example. As she speaks, we can hear her “vision” inventing itself as she goes along.

Devlin: Do you follow the drift of my argument?

Rebecca: Oh yes, there’s something I’ve forgotten to tell you. It was funny. I looked out of the garden window, out of the window into the garden, in the middle of summer, in that house in Dorset, do you remember? Oh no, you weren’t there. I don’t think anyone else was there. No. I was all by myself. I was alone. I was looking out of the window and I saw a whole crowd of people walking through the woods, on their way to the sea, in the direction of the sea. They seemed to be very cold, they were wearing coats, although it was such a beautiful day. A beautiful warm, Dorset day. They were carrying bags. There were… guides… ushering them, guiding them along. They walked through the woods and I could see them in the distance walking across the cliff and down to the sea. Then I lost sight of them. I was really quite curious so I went upstairs to the highest window in the house and I looked way over the top of the treetops and I could see down to the beach. The guides… were ushering all these people across the beach. It was such a lovely day. It was so still and the sun was shining. And I saw all these people walk into the sea. The tide covered them slowly. Their bags bobbed about in the waves.

These things haven’t happened in Dorset. But they have happened. Rebecca’s imaginings are large, and, to us, disturbing. What makes them more disturbing is the near-detached tone in which she relates them.

It strikes me that, whether by accident or not, Rebecca resembles the speaker of Wallace Shawn’s play The Fever, who addresses, head on, the killings of American foreign policy and cannot reconcile them with the peaceful domesticity of life at home. This way madness lies. In Ashes to Ashes, though Devlin is, in part, concerned for Rebecca, he also wants to possess her, to control her, to claim he knows her, and not to inquire about her visions – which are of mass deaths, people’s flights from genocide, the Kindertransport, the massacre of the innocent. Here’s the climax of the play:-

Devlin: What do you say, sweetheart? Why don’t we go out and drive into town and take in a movie?

Rebecca: That’s funny, somewhere in a dream… a long time ago… I heard someone calling me sweetheart.

Pause.

I looked up. I’d been dreaming. I don’t know whether I looked up in the dream or as I opened my eyes. But in this dream a voice was calling. That I’m certain of. This voice was calling me. It was calling me sweetheart.

Pause.

Yes.

Pause.

I walked out into the frozen city. Even the mud was frozen. And the snow was a funny colour. It wasn’t white. Well, it was white but there were other colours in it. It was as if there were veins running through it. And it wasn’t smooth, as snow is, as snow should be. It was bumpy. And when I got to the railway station I saw the train. Other people were there.

Pause.

And my best friend, the man I had given my heart to, the man I knew was the man for me the moment we met, my dear, my most precious companion, I watched him walk down the platform and tear all the babies from the arms of their screaming mothers.

Silence.

Devlin: Did you see Kim and the kids?

She looks at him.

You were going to see Kim and the kids today.

She stares at him.

Your sister Kim and the kids.

Rebecca: Oh, Kim! And the kids, yes. Yes. Yes, of course I saw them. I had tea with them. Didn’t I tell you?

Of all the moments in all the plays I’ve reviewed over the years, I don’t think any has felt stranger than Devlin’s question “Did you see Kim and the kids?” At the Royal Court world premiere in 1996, it seemed such an act of denial on his part, such a refusal to attend to her astonishing testimony, that it felt like being slapped in the face - like walking into a brick wall. But I was lucky enough to be able to watch Pinter’s original production, with Lindsay Duncan and Stephen Rea, over some seven months, first in London, later in Dublin, four times in all. And in due course I came to realise that Devlin here is trying, however questionably, to restore her to the real world, trying to bring her back to her senses. And he succeeds, for the moment.

He pulls her back from the brink a few more times. But it never lasts. She keeps withdrawing into this other world, of what strikes us as horror, but is in fact worse - because it is a virtually calm complicity with horror. I really don’t believe she has ever experienced this trauma in her own life; Ashes to Ashes is Pinter’s mosr dismaying psychodrama; I think Ashes to Ashes is Pinter’s most disturbing psychodrama. Unlike Rebecca, Devlin is utterly sane. He is lucid, and, partly, a figure of pathos and compassion, trying to comprehend her. Another part of him, though, is more dictatorial; and, like every bully in Pinter, he senses his own weakness. He makes matters worse when he tries to get her to re-enact with him her memories of a fascist brutalist lover. He tries to possess her fantasy, and his manner of doing so suggests to me that Rebecca’s fantasies of the fascist monster she recalls having loved are really dreams of this man she has been living with all along, Devlin.

Now, eluding him forever, she is locked in memories that aren’t memories. She talks about her baby, then says she doesn’t have a baby. There is, finally, no dialogue now between her and Devlin, only between her and an echo of herself. The echo partly tells us that she is now stuck in her own imaginings and can hear nothing else. But it tells us, too, that she is dreaming of something: a baby, somebody’s baby, anybody’s baby. Rebecca’s dreams, her madness, are larger, more sane than Devlin’s sanity. Does drama get stranger than this?

I met Pinter a few days after the premiere of Ashes to Ashes. He asked me if I would be seeing it again. I said yes, I would be going back to it in a few days’ time. He asked me to let him know what I made of it after this second viewing. So I did. I behaved like a good schoolboy: I wrote him a long letter, in which I explained the four or more main ways, each quite different, in which I felt the play could be interpreted. In one of these, I said that Rebecca, however deranged she might seem, was nonetheless in touch with the larger crimes against humanity of our time, whereas Devlin was deliberately deaf to them; and that Rebecca and the play therefore were saying “No man is an island”. It took pages. I don’t do short; Pinter does nothing but. His reply said mainly this:

Dear Alastair,

Your letter was a good read!

‘No man is an island.’

That’s it. On the nail.[3]

And, if I understand Pinter’s plays aright, it is his women – some of them – who comprehend best that no man is an island. They are the divining rods of identity that commune with larger aspects of feeling and experience, sometimes at terrible personal cost. Really, the dialectic of Ashes to Ashes is the dualism that we can discern within Pinter’s own thought in his Nobel acceptance speech. On the one hand, there are facts; on the other, uncertainty. On the one hand, there is denial; on the other, there is open witness and serious re-imagination of trauma, of death, of horror, even though these may be inextricably connected to love and loyalty.

How do we reconcile the two? It seems Pinter does it by giving voice to masculine and feminine sides of himself – and thereby finding those voices within us too.

[1] In the versions printed in both The Spectator and Faber, there is a full stop after the second line. Pinter stated that this is erroneous.

[2] He died on December 24, 2008.

[3] Later that year, Pinter, speaking to The New Yorker, said that Ashes to Ashes says “No man is an island.”

1: Lindsay Duncan and Stephen Rea in the world premiere production of Harold Pinter’s “Ashes to Ashes” (1996), directed by Pinter himself.

2: Judi Dench and Anna Massey in the world premiere production of Harold Pinter’s “A Kind of Alaska”.

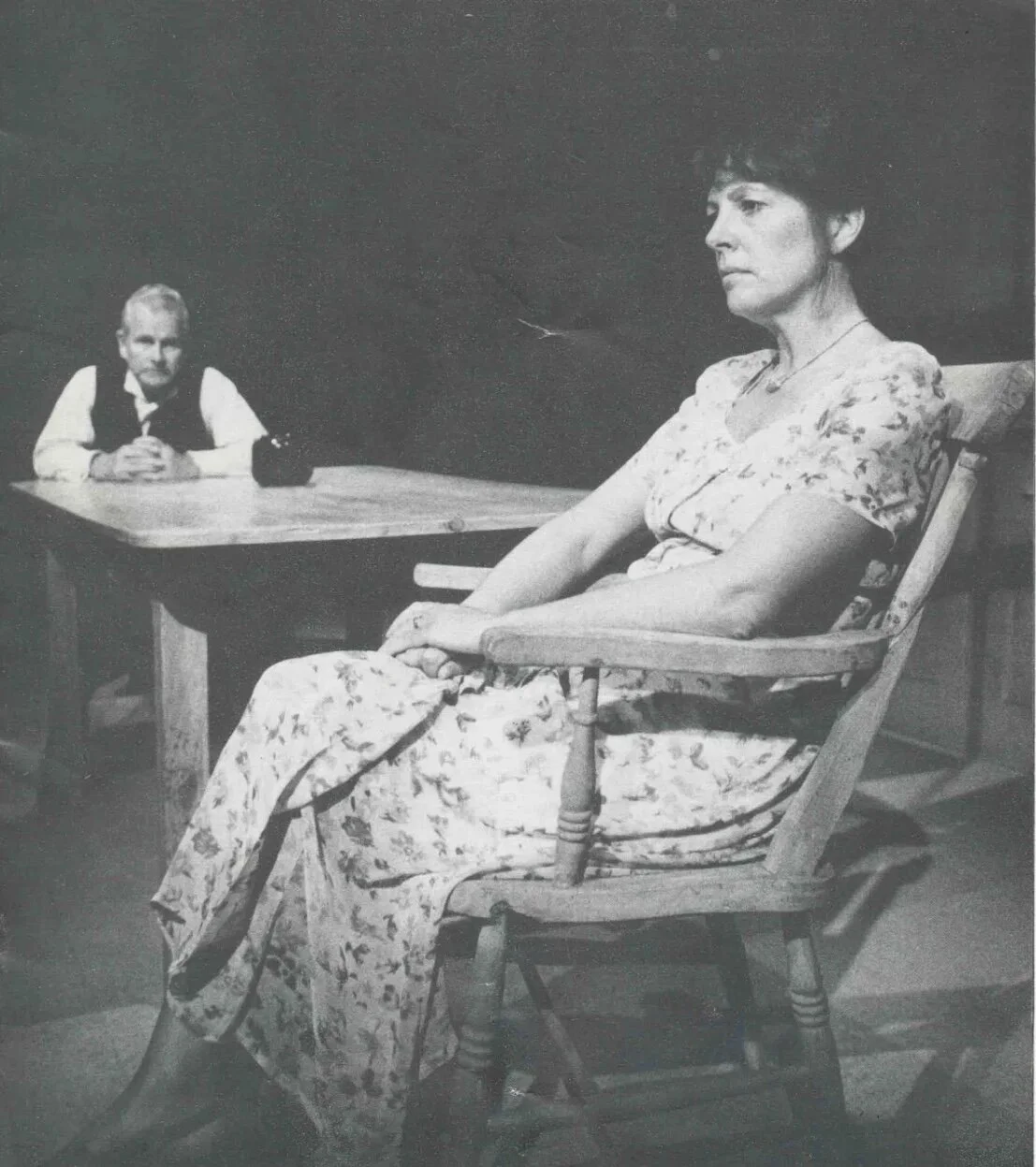

3: Ian Holm and Penelope Wilton in Harold Pinter’s 1994 production of his own one-act “Landscape” (1968). This production, among the most perfect I have ever seen of any play, began life at the Gate Theatre, Dublin’s, 1994 Pinter Festival. Later that year, it transferred to the National Theatre’s Cottesloe Theatre.