The juba and the American black origins of tap dance - Black History Month in dance, 9

49; 50; 51. For Black History Month in dance, every dance-goer who has not already read Brian Seibert’s “What the Eye Hears - A History of Tap Dancing” (2015) should start doing so. It’s a big book, over six hundred pages, and yet it’s worth reading slowly and thoughtfully because it opens up so many examples of dance. Do read it with the help of an iPhone or IPad - as I did - so that you can keep googling Seibert’s wealth of research.

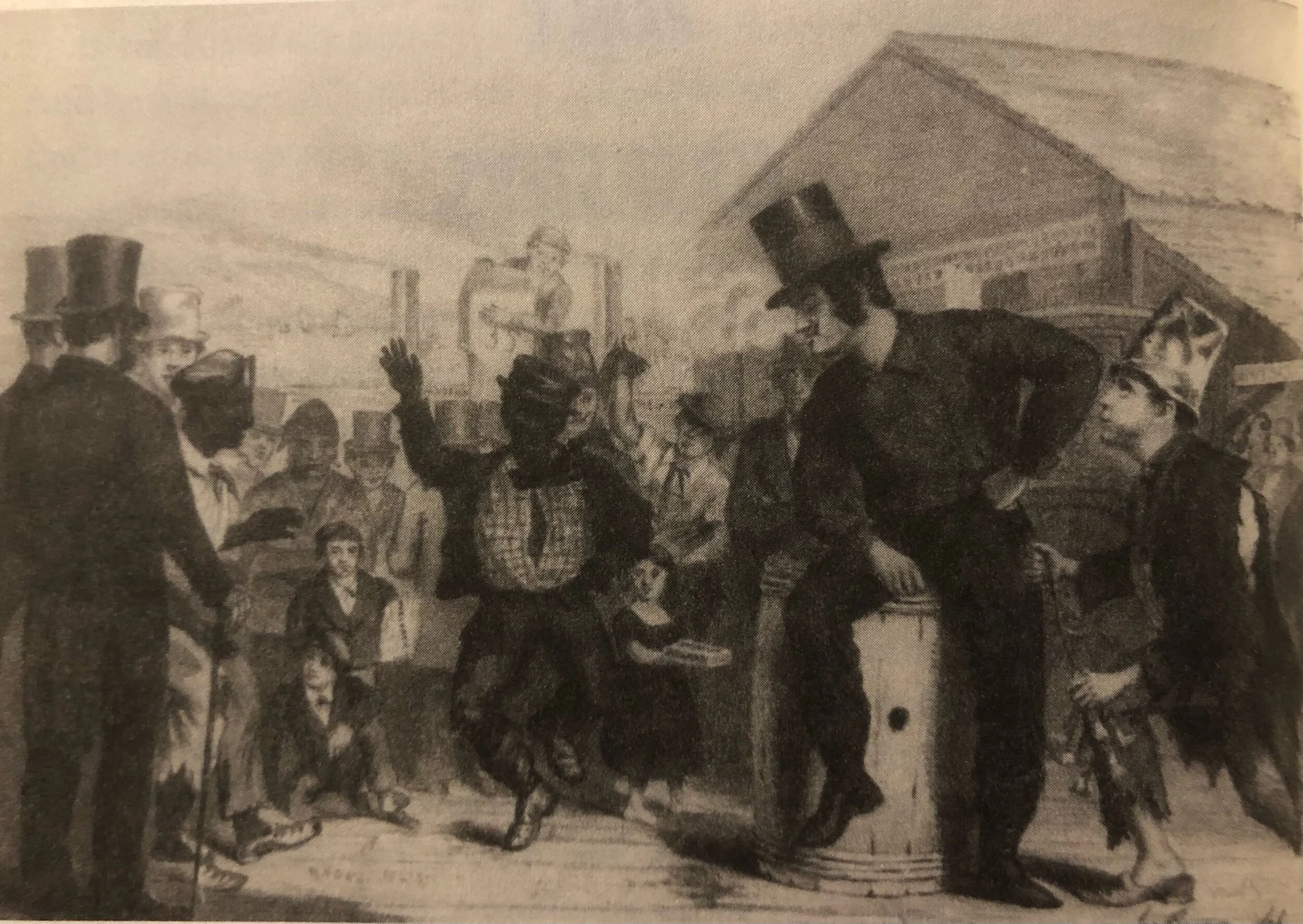

Here, for example, are three images of early nineteenth-century images of juba, one of the forms of black dance - specifically a form of jig - that was an antecedent of American tap dance. 47, an 1848 illustration of the Chatham Theatre’s production of the popular play “New York As It Is”, centres on Jack, “a Negro and Dancer for Eels”; Seibert observes Jack’s pose is close to that of 48, some 1840 sheet music for “Jim Along Josey”, and 49, an illustration of John Diamond, master of the Long Island breakdown. (Seibert reproduces 47; he describes 48 and 49, but you can google them to check them out.)

And so a sociology begins to emerge: not just how black men danced to entertain in America but how they were seen and watched by others. I’m addressing here only one page of Seibert’s book; every page opens up much. Larger than dance, the book’s subject is race, principally race in America. As Seibert shows, tap has long been the domain of white as well as black people, and it has white as well as black antecedents, but it is far from colour-blind; race remains an important issue within it. The principle that “Black Lives Matter” underlies “What the Eye Hears”, among the most instructive and mind-opening books on dance I have ever read.

Tuesday 9 February