Dante’s “Divine Comedy” according to Wayne McGregor, Thomas Adès, and Tacita Dean

Was Ninette de Valois right or wrong to claim, as she did around 1949, that the three-act ballet was the future of the art? The debate continues, nowhere more so than at Covent Garden. In eleven years, pandemic notwithstanding, the Royal Ballet has presented the premieres of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (2011), The Winter’s Tale (2015), Woolf Works (2015), Frankenstein (2016), and now The Dante Project in eleven years, all to commissioned scores. My own experience is that our century’s best ballets have been one-acters created in New York, and that its greatest full-length works (Merce Cunningham’s Nearly Ninety, Pam Tanowitz’s Four Quartets) have been barefoot modern-dance creations – but I enjoy the debate.

The three-act format poses compositional challenges quite unlike the two-act one. How to shape Acts One, Two, and Three into a memorably suspenseful architecture? (Especially with the monstrously long intervals between acts standard at Covent Garden?) The Dante Project has an element of narrative – the poet and protagonist Dante is taken through successive realms of the Christian afterlife, the Inferno: Pilgrim (Act One), the Purgatorio: Love (Two), and Paradiso: Poema Sacro (Three) – but its overall method is to give us three strikingly unalike zones, each of which goes on changing and introducing new levels of thought and experience. It’s as if we see three different forms of the same element: coal; carbon; diamond.

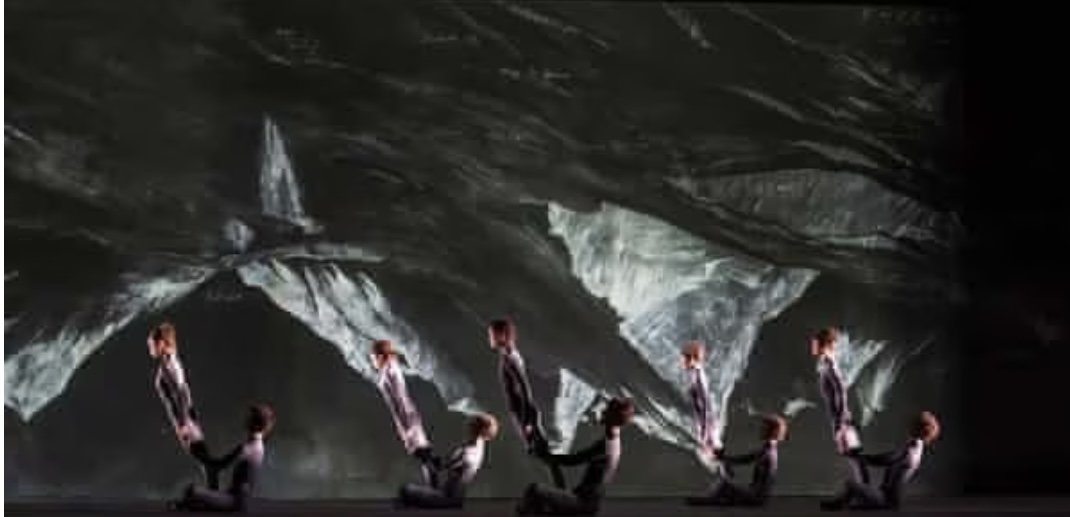

This Dante Project has six main makers: composer Thomas Adès (he also conducted the initial performances), choreographer Wayne McGregor, designer Tacita Dean, dramaturg Uzma Hameed, and lighting designers Lucy Carter and Simon Bennison. It’s Adès and Dean who have most evidently conceived this creation as a tripartite architecture. Adès’s Inferno (much the longest part of the trilogy) takes us through a series of late Romantic soundworlds, chiefly ones created by Franz Liszt, whose scores Adès plunders shamelessly, while Dean’s changing décor is chiefly a cavern, whose craggy ceiling (an upended mountainscape) seems inspired by Gustave Doré’s engravings.

With Purgatorio, Adès takes us to an amalgam of religious chants from different sources, often punctuated by knells like depth charges, while Dean gives us a slanted view of a painting of a green-leaved jacaranda tree before a view of modern housing. And the music for Paradiso - here Messiaen is Ades’s inspiration - is almost all ecstatic scales and ascents, while Dean’s visual look is space-age, with a film of abstract colours projected above the dance space.

Yet I wish Hameed, the dramaturg, or someone at Covent Garden had drawn Adès’s and Dean’s attention to the extent their work here reminds Covent Garden viewers of other familiar works. Adès’s Inferno music uses several of the same Liszt items as John Lanchbery’s score for Mayerling (many ballet-goers immediately recognized music they associate with the Hofburg and also the shooting-in-the-snow scene) and a stupidly oompah Galop; Dean’s two-dimensional, only partly coloured Purgatorio tree looks flat and pallid to all who know the magical, three-dimensional one designed by Bob Crowley for Act Two of The Winter’s Tale.

Film, though not an element new in dance theatre, here does nothing to create a theatre of marvels. And why is so much of the surrounding space so Stygian-black in both Purgatorio and Paradiso? The idea of changing Dante’s costume from turquoise (Inferno) to bipartite turquoise/scarlet (Purgatorio) and so to scarlet (Paradiso) is awkwardly realized. Despite his attire’s connections to Dante illustrations by Botticelli and Blake, its cut (a calf-length housecoat with a quasi-mediaeval shoulder-drape over bare legs) is altogether awkward.

McGregor’s choreography is surely his most conformist – but also varied - to date. There’s none of his old penchant for head-jutting. (Some expressive sideways head-tics in the Purgatorio, mind you.) The quantities of expressionist gesture (self-stabbing, above all) seem un-McGregor. Although the dancing features plenty of hyperextension, this is used with discrimination: the prolonged, seraphic open-legged body language of lifted women in the Paradiso is far from the high-kicking torment of Dante’s opening Inferno solo.

And McGregor gives individual Inferno characters their own idioms. If you know your Inferno, you recognize Paolo and Francesca on their first appearance, especially with first-cast Francesca Hayward and Matthew Ball. But more than one of us thought Dante’s first sustained duet was with Beatrice: actually it’s with Satan - a disastrous error of characterization on McGregor’s part.

With the second cast – Federico Bonelli as Dante, Fumi Kaneko as Beatrice – some three-dimensional sculptural beauty and dynamic drama emerged. Two examples, both from Paradiso: when Kaneko travels down the stage centreline towards Dante, her bourrées radiate deep into the theatre; when Bonelli promenades her by the hip in a tilted attitude, we immediately sense Dantesque qualities of chivalry, courtesy, and sublimity. When the same moments occurred on opening night with Edward Watson and Sarah Lamb, they lacked eloquence. Let’s hope that Watson’s extreme physical tension (his shoulders are hoisted high throughout) and Lamb’s polite blandness were due to first-night strain.

Even so, McGregor doesn’t bring his artistic elements together well. Purgatorio ends with some of Adès’s most urgent, vivid, innovative, pulsating music, but the long dance duet for Dante and Beatrice that accompanies it seems weirdly unconnected to what we hear. A problem throughout this whole Dante trilogy is not McGregor’s choice of movements but his weak phraseology. The dances don’t cohere rhythmically. As yet, the thrilling ambition of The Dante Project seldom fuses into living dance theatre.

<Originally published in Dancing Times, November 2021>

@Alastair Macaulay, October 2021

1: “The Dante Project”: Gary Avis (Virgil) with Edward Watson (Dante). Photograph: Tristram Kenton.

2: “The Dante Project”, Inferno: Pilgrim scene. Photograph: Foteini Christofilopoulou.

3: “The Dante Project”: Edward Watson (Dante) with Fumi Kaneko (Satan). Photograph: Foteini Christofilopoulou,

4: “The Dante Project”: Edward Watson (Dante), Sarah Lamb (Beatrice). Photograph: Andrej Uspenski.

5: “The Dante Project”: Purgatorio. Left to right: Joseph Sissens, Matthew Ball, Calvin Richardson and Ryoichi Hirano. Photograph:

Andrei Uspenski.

6: “The Dante Project”: Edward Watson (Dante) and Marco Masciari. Photograph: Andrej Uspenski.

7: “The Dante Project”: Inferno: Pilgrim. Photograph: Tristram Kenton.