Poussin and the Dance (to the music of time)

<originally published in “Dancing Times”, November 2021>

The National Gallery introduces its new “Poussin and the Dance” exhibition with the premise that Nicolas Poussin (1595-1665) is the most important and/or influential French artist before Manet. Is he? The National is a good place to make a counter-argument: J.M.W.Turner, bequeathing many of his paintings to the nation on his death in 1851, stipulated that two of them should hang in the National between two by Poussin’s contemporary Claude Lorrain (1600-1682), making a quartet that remains one of the gallery’s most enduring and valuable statements. Even so, “Poussin and the Dance” – at the National until January 2, 2022 - makes a beautiful and original exhibition. Marvellously, it casts new light on this influential artist, since dance is an element often overlooked in Poussin.

Paradoxically, Poussin achieved his eminence among other French painters by spending most of his final forty-one years in Rome. There, he absorbed himself in the classical traditions of Greece, Rome, and the Italian Renaissance. During the first thirteen years of that Roman residence (1624-1636), part of what fascinated him in classical art was its depiction of dance.

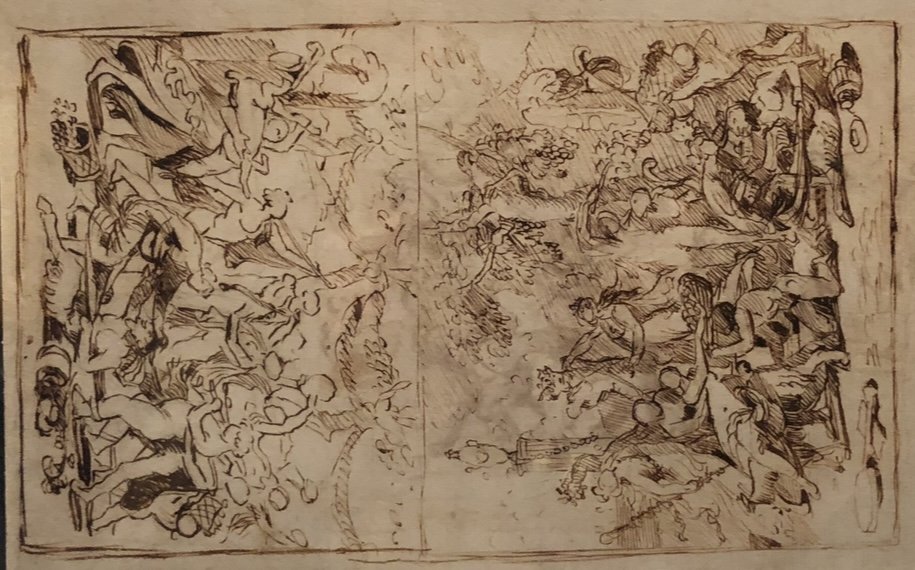

This exhibition shows the stunning ancient Roman vases that mattered to Poussin, allowing us to see what he derived from them. It also shows how he prepared his work. Poussin, it emerges, needed to make three-dimensional sculptural wax models before he painted people in motion. Although those models are now lost, modern artists have here provided substitutes.

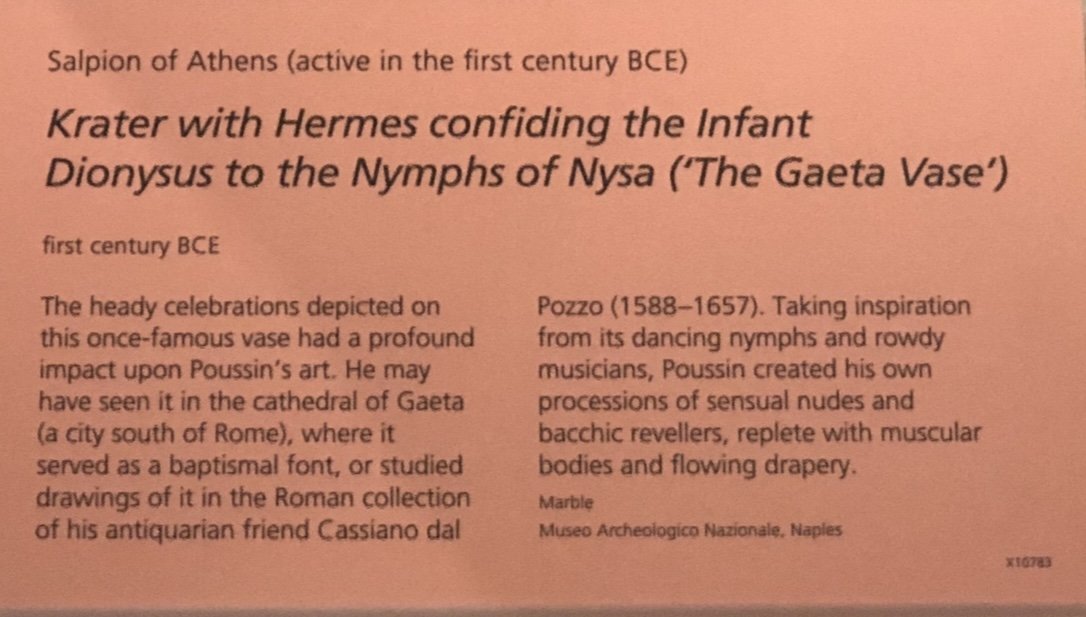

Yet Poussin seems never to have painted the dancing of his day. Peculiarly, the National Gallery makes no comment on this. The dancing he drew and painted is all mythological (including Old Testament subjects). We’re shown how keenly he derived dance ideas from three Graeco-Roman masterpieces from the first century BCE and second century CE: the “Gaeta Vase”, the Borghese vase, and the “Borghese Dancers” relief. But do the creators of this exhibition really suppose that Poussin was so divorced from his own times that his paintings carry no trace of the life outside his studio? And what would it say about him if he did indeed in no way reflect the moment in which he lived?

Every work of art carries in it the time of its creation; every subsequent interpretation of the Graeco-Roman tradition imposes its own anachronistic ideas. In what ways was Poussin’s vision of dance shaped by the dancing of the seventeenth century? Alternatively, if Poussin’s ideas of dance in 1624-1636 were far removed from the social and theatrical dancing of Paris and Rome in that period, what kind of escapism on his part does that represent?

Much of the dancing he showed is barefoot, performed with clothing that reveals plenty of bare flesh elsewhere. In these and other respects, he’s escaping to a world surely unlike that of the baroque courts and theatres.

Even so, it’s striking that Poussin’s dancers’ legs seldom rise high. Arms tend to be kept below head-height except with some Bacchic revellers. When deportment veers from the vertical, that implies inebriation, ecstasy, or some other departure from harmonious convention. Poussin may well, at least in some respects of physical behaviour, have been echoing the dancing of his day.

And he anticipated aspects of the ballet classicism that was to follow. Inspired by Raphael and other masters of the Italian Renaissance, was establishing French classical form. Poussin may well have been among the sources of those who went on to make ballet a classical genre after his death. In this respect, it’s especially striking to see two pen-and-ink drawings of a male votary of Bacchus from c.1635: almost nude, the dancer rises high on his toes (keeping the knee of his supporting leg bent), balancing on one foot. The shape he makes is an early form of ballet attitude croisé – but the way he stretches his torso to address out gaze while holding his head and arms in profile creates a thrillingly sculptural tension.

For many people, one single painting forever links Poussin to dance: “Dance to the Music of Time” (1634), a celebrated allegory that has long hung in London’s Wallace Collection and which gave its name to a celebrated cycle of twelve novels (1951-1975) by Anthony Powell. This is not a painting to be absorbed in a quick glance: it’s truly multidimensional. Though the central four figures are dancing in a ring, all four face outwards, their hands joined. (Try that.) One, Poverty, is a man, with his back to us. Maybe he and two of his companions, Pleasure and Labour, are dancing clockwise, all currently with weight on the left foot but perhaps preparing to transfer weight to the right as they move to their right. Yet Wealth, in the foreground (she alone wears golden sandals), is out of step with the others, her weight on her right foot. And Pleasure, on the left of the group, is looking to her left – directly at us - with no regard for Poverty, even though she may be heading his way.

The winged but naked old man, strumming the lyre and conducting the dance, is Time. The pillar on the left has a Janus pair of heads facing in opposite directions. (Janus, Roman god of doorways, faced both forwards into the future and backward to the past.) A baby on the left blows soap bubbles; a baby on the right inspects a salt-cellar clock. In the sky above, Apollo drives his chariot across the morning sky, preceded by Dawn (scattering rose petals as she goes) with the Hours following in his wake. Movement and stillness are juxtaposed throughout the painting, but at its heart is a dance that is poetic, absorbing, yet uneven, even unbalanced.

Poussin painted this pagan work for Giulio Rospigliosi (1600-1669), who, for the final two years and a half of his life became Pope Clement IX: it was Rospigliosi who dictated its iconography to the painter. The exhibition’s other three other climactic works - “The Triumph of Pan”, “The Triumph of Silenus”, and “The Triumph of Bacchus”, all realized in 1635-1636 - are visions of pagan riot (maenads, satyrs, commissioned by France’s most eminent priest, Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister of the French king Louis XIII. Rospigliosi was passionately involved with the performing arts, writing dramas, poetry, libretti, and what may have been the first comic opera; Richelieu was a patron of the playwright Corneille. These men were leaders of the late Counter-Reformation: clerics determined to be involved in the secular. Still, it’s a shock to imagine the Bacchanalian “Triumphs” on the Cardinal’s walls.

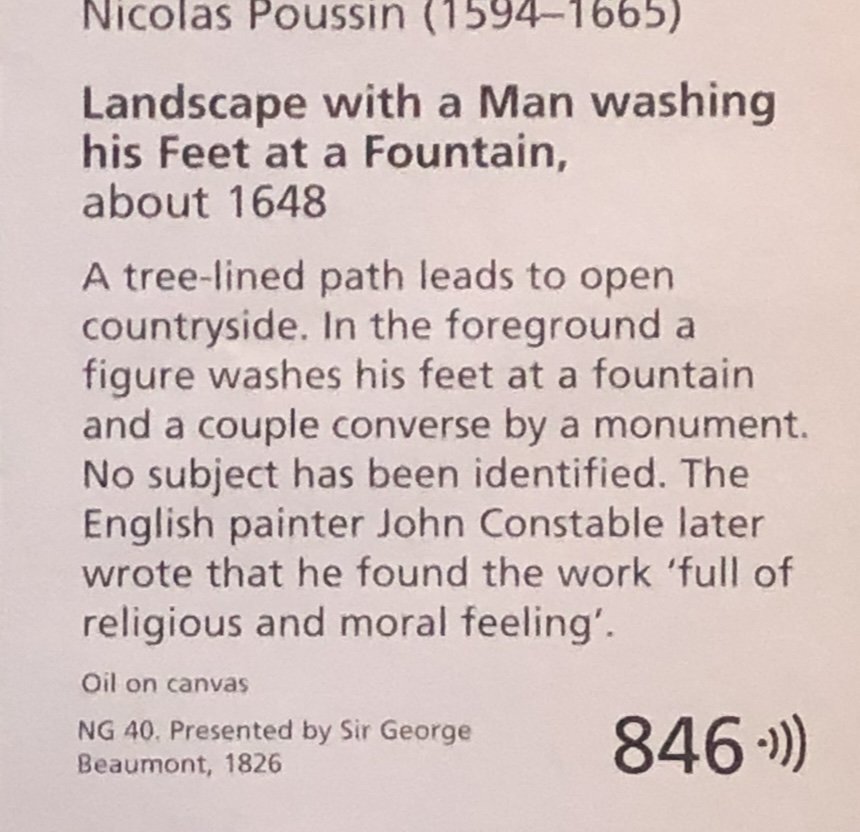

Dance is an element that Poussin eschewed in later years. To my mind, he became a yet greater painter. This exhibition is in the heart of the National Gallery: it’s not many rooms from his “Landscape with a Man killed by a Snake” and “Landscape with a Man washing his Feet at a Fountain” (both probably painted in 1648). The movement in these paintings is poignantly juxtaposed against layered scenery: matters of humanity are set within larger content to sublime philosophical effect. Poussin, we can see, never lost his feeling for movement and gesture. Even without real dancing, his mastery of choreography grew only more profound.

@Alastair Macaulay 2024