Jasper Johns on Merce Cunningham - nineteen questions (one about Margot Fonteyn) and nineteen answers

In 2012-2013, the Philadelphia Museum presented an important exhibition of Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, and Jasper Johns. This opened less than a year after the closure of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company: most of its members were able to perform in the numerous dance events that occurred as part of the exhibition. Jasper Johns was the only living member of the exhibition’s five artists; he had been a friend of Cunningham’s since the 1950s, served as artistic advisor to the company between 1967 and 1980, and took a close and admiring interest in Cunningham’s work until and after Cunningham’s death.

Johns and I had met a few times by then; I knew he welcomed my reviews of Cunningham dance theatre as chief dance critic of the “New York Times”. Although he tends to use few words in conversation about dance, he proposed that I interviewed him by email. In due course, I sent him eighteen questions.

Most of his replies were brief; considerable “New York Times” editing occurred before the eventual piece was published. Here, however, are his original replies, supplemented by one more question and answer from 2021.

It should not be thought that the shortness of Johns’s replies to my questions indicates haste or rudeness on his part: he is renowned for being enigmatic. I know that he took time to word these replies and discussed some of them with mutual friends. While enigmatic, they show his concern with honesty, accuracy, and facts.

AM1. This Philadelphia exhibition honors five artists: Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Robert Rauschenberg, and yourself. Cage and Cunningham had been working together since 1942; you and Rauschenberg became, with them, an artistic quartet of friends in the 1950s. I hope it's fair to say the four of you, despite being strong individuals with separate qualities each peculiar to himself, represented a new movement in the arts. Robert Rauschenberg worked closely with the Cunningham troupe as its main designer from 1953 to 1964, and you unofficially assisted in the realization of some of his designs; from 1960 onwards you and other artists began to sponsor some of Cunningham's seasons; in 1967, you became the company's artistic advisor, a post you officially held until 1980. You were in Cunningham audiences right up to the final year of his life and after.

The senior figure of the five was Duchamp. And the work that most overtly connects him to you and Cunningham is "Walkaround Time" - which came to the stage in 1968. How do you remember having this idea? and how do you remember shaping it with Cunningham? and with Duchamp?

JJ1. One doesn’t usually know where ideas come from, but I think the trigger for the Duchamp set was seeing a small booklet showing each of the elements of the Large Glass in very clear line drawings. I occurred to me that these could be enlarged and incorporated into some sort of decor. Merce was agreeable, if I would be the one to ask Marcel for permission. Duchamp was agreeable if I executed the work.

AM2. I know "Walkaround Time" only as a wonderful film (made in live performances by Charles Atlas). Even there, it has a luminous quality. its light and color are gorgeous. But the composite parts of "The Large Glass" that you made was often used by the Cunningham company in subsequent years for Events. I can see ways in which Cunningham was working to absorb aspects of Duchamp's work - his striptease solo (a reference to "Nude Descending a Staircase"), the non-intermission in which dancers didn't dance, the serene solo for Carolyn Brown with its use of astonishing stillness. Was "Walkaround Time" also a chance for you to absorb yourself more deeply than (even) before in the work and thought of Duchamp?

JJ2. I think that I was fully occupied trying to get the set completed in time,

AM3. Many Cunningham dances had private ideas - things that helped him to make the dance but which he didn't share. I've sometimes thought I could see references to chess that may have referred to the games Duchamp had with Cage; he often had one woman lifted or partnered by three or more men in what may have been his private reference to Duchamp's Bride and her Bachelors. In "Enter", finshed after Cage's death, he gave himself a solo of standing still in three successive places across the stage - a reference to the three sections of Cage's "4'33"." Did he share any such references with you?

JJ3. Not that I recall. Cage was more apt to have been privy to such thoughts.

AM4. It's famous that the music and design for Cunningham dance theater were composed apart from the choreography. Still, there were a few exceptions, and certainly Cunningham either gave a few ideas or listened to others from his collaborators. I think for “Winterbranch" (which the Los Angeles Dance Project is currently reviving) he told Rauschenberg: "Think of the night as if it were day"; to William Anastasi for "Points in Space" he said "Think of weather"; to Suzanne Gallo for "Pond Way" he said "Think misty". When he was making "Doubles" (a piece he loved to rehearse in his final months), Cage came to rehearsals and suggested that there be two moments when the stage completely emptied for a while; when Rauschenberg told him the costumes for "Nocturnes" would be all white, Cunningham said "Then I won't put any falls in it". Do you remember any particular ways in which you took suggestions from him, or gave them to him, for "Walkaround Time"?

JJ4. No. I don’t remember that I watched “Walkaround Time” rehearsals. I believe that I may have given Merce dimensions of the various “boxes” to help him allow for their presence on the stage.

AM5. John Cage was not officially involved with "Walkaround Time" - but it involved three artists dear to his heart. Do you remember him being around during the planning or rehearsal or performance period? Did he contribute in any way?

JJ5. I don’t know.

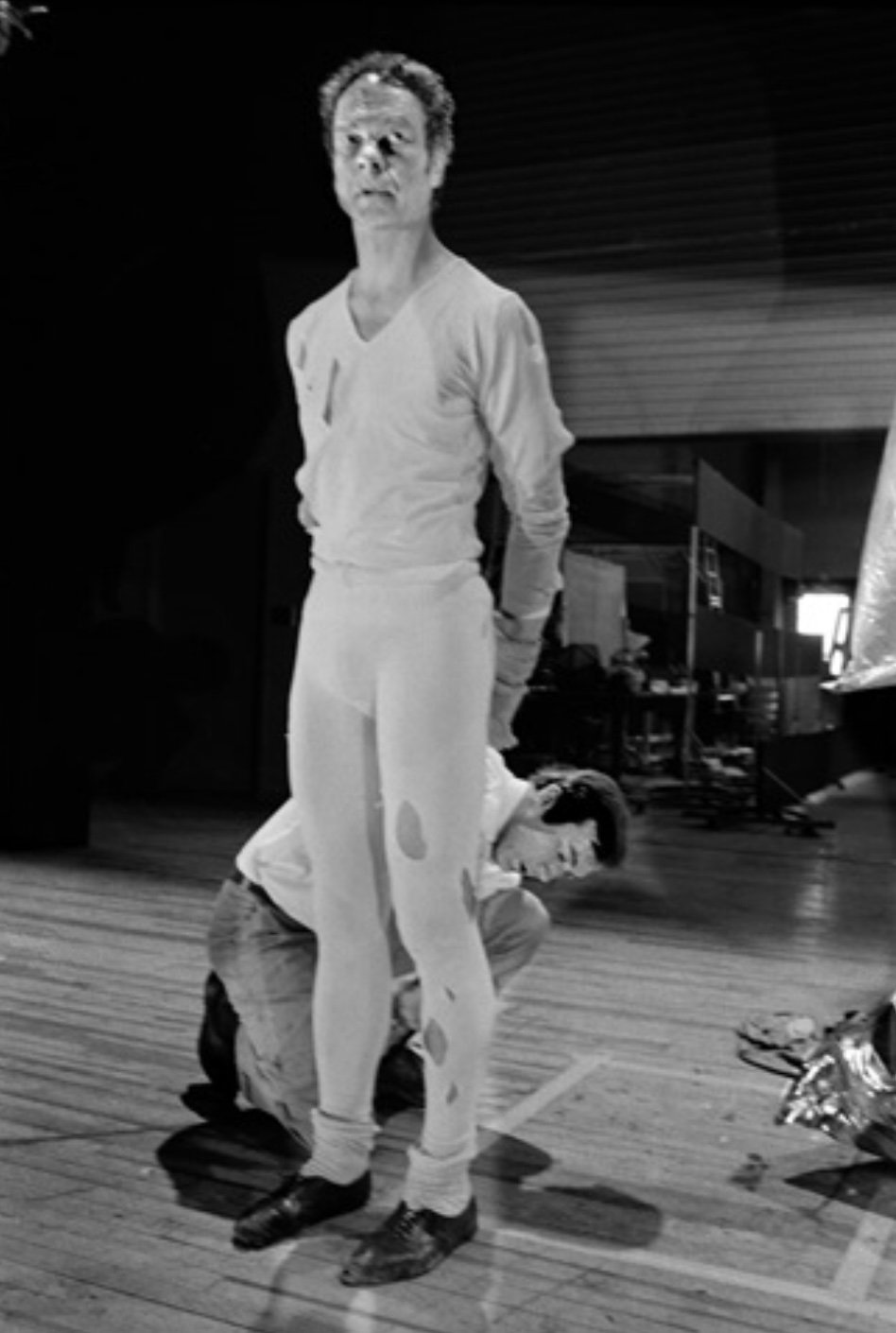

AM6. Earlier that year, you designed the costumes for one of Cunningham's most celebrated and revived works, "RainForest". The decor is famous: silver helium-fillowed pillows by Andy Warhol, some of them free-floating and unpredictable. Can you tell how you came to make the costumes, those flesh-colored woollen tights with slashes revealing bits of the dancers' bodies?

JJ6. I had asked Andy to design costumes to go with the pillows, but his only suggestion was for the dancers to be nude, an idea that had no appeal for Merce. Merce showed me an old pair of his tights that were ripped and torn. I imitated these.

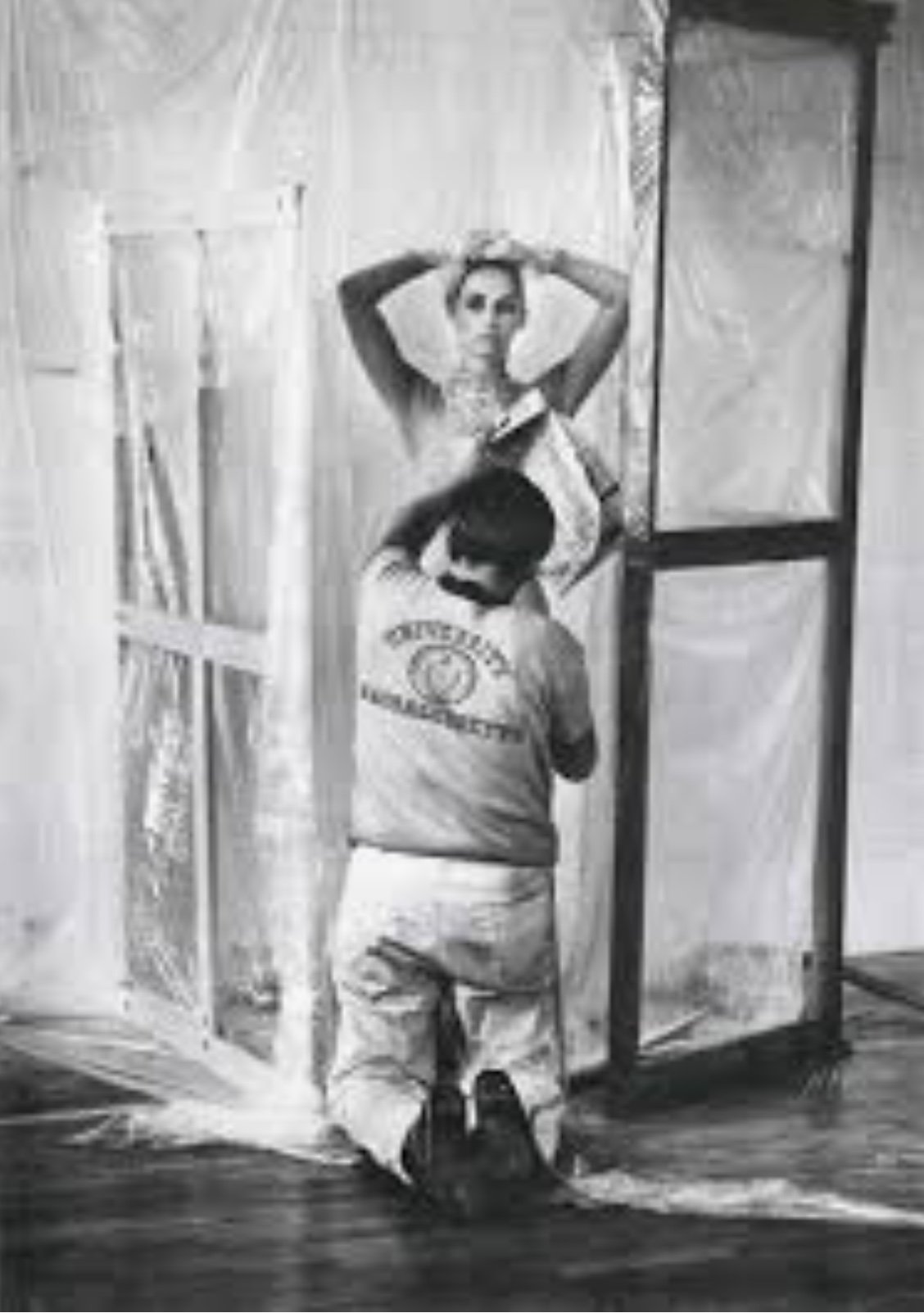

AM7. Carolyn Brown was very proud of wearing the "RainForest" costume that you had torn with a razorblade. And there is a photo of you spray-painting her costume for "Canfield", a work for which you were - presumably by choice - uncredited. Your paintings show the delight you take in the tactile work of brushstrokes: did you feel a related pleasure in working on the practical side of stage design? And/or did you find it frustrating?

JJ7. Both, at different times.

AM8. In 1970, Cunningham made "Second Hand"; you made the costumes, which spanned a rainbow spectrum of color when seen all together. Do you remember what gave you that idea?

JJ8. No. I only remember that Viola Farber told me that they looked “like a bunch of Easter eggs.”

AM9. We now know that Cunningham planned "Second Hand" to fit Erik Satie's "Socrate"; he wasn't allowed by the Satie estate to use that score, and so Cage composed "Cheap Imitation" for piano, to match its rhythmic structure. Only after the premiere did Carolyn Brown, who had a long duet with Cunningham, find from Cage that Cunningham had seen himself as Socrates in this work. Were you given any clue of the Socratic subjectmatter?

JJ9. No.

AM10. One of the Cunningham works of which we know too little today is "Landrover" (1972). It lasted fifty minutes. You made the costumes, apparently in a range of colors. Do you have any particular memories of this?

JJ10. No.

AM11. The next work of 1982, "TV Rerun", seems to have been partly your idea. Cunningham was looking into ways of shifting focus onstage. Apparently you had the idea that camera men might move around the stage. And you were credited with the design. One or more persons onstage was to photograph one or more of the others. What are your memories?

JJ11. None.

AM12. 1973 brought a magnum opus: "Un Jour ou Deux", choreographed for the Paris Opera Ballet. You designed two scrims; and put the dancers into costumes that shaded vertically upward from dark to light gray. Do you remember why you conceived those design ingredients?

JJ12. No.

AM13. You assigned the realization of your Paris Opera designs, and for the costumes for the 1974 "Westbeth" to your young colleague Mark Lancaster, who gradually became more and more absorbed in the work of the Cunningham company and made many superb designs for it himself. But in 1978 you returned to work for the company, designing both scenery and costumes for "Exchange". I remember this as a great work; to me, it felt both tragic and like watching the passing of history. Cunningham danced the lead: the first section featured half the dancers, the second the other half, and only he was a constant figure. Your costumes had a range of color, but all with a strong admixture of gray. What are your memories of the conception and planning of this work?

JJ13. Actually, the realization was carried out in some backstage room where Mark and I worked directly on dyeing the costumes, having been refused the possibility of taking them to a more convenient workplace. Opera officials explained that, if we removed their property from the premises, it might be lost. I doubt that the image that I had in mind for “Exchange” was conveyed by my work - smoldering coals, covered by ash.

AM14. Cunningham was almost sixty when "Exchange" had its premiere; this was perhaps his last full-out role, and he went on dancing it till about the age of sixty-two. He was no longer doing the jumps that had been a forte of his. Gradually in the 1980s and early 1990s he began to give himself less taxing roles, smaller or even supporting roles, as he became more limited and arthritic. Because he was a natural stage animal, he was always riveting - but he was also controversial, both among viewers who could "remember him when" and among newcomers who had no comparable experience. I loved his performing in these years, but it was certainly a challenge. How did you find it to watch him onstage at that time?

JJ14. An answer would be too complex for me to formulate.

AM15. I had heard that he and Margot Fonteyn had a mutual admiration society, with talk of dancing in a duet by him. That never happened, but he told me in the 1990s that it was you who was keen on this. (And he had a favorite story of going to her apartment in New York, where he overheard her talkingh about the cost of her stepdaughter's wedding and saying "Oh well, I shall just have to dance one more 'Swan Lake'".) Did you know Fonteyn well enough to try bringing her and Cunnigham together? (I am a Fonteyn obsessive, Jasper, so am asking this question more for my own sake than for the "Times"!)

JJ15. I met Fonteyn and her husband at the Jacob Javits’ apartment and saw Margot a few times. She visited my studio on East Houston Street when Mrs. Javits was trying to convince her that she should have a loft in New York. I don’t remember why, but I did suggest to Merce that he make a dance for her. Perhaps the idea came from feeling that someone other than Cunningham Company could perform his work and that this might best be shown by someone as distinguished as Fonteyn. Merce and John seemed OK with the idea and we visited her on Central Park South.

At some point, Merce said,” Margot, I would like to make a dance for you.” She seemed to find the possibility interesting and as she thought about it she said that she would do it if Merce would dance with her that, perhaps, they could perform for some charitable benefit.

We left and the following day Cage called me to say that Merce was not going to do it. I asked why not. “He can’t. What would Carolyn think?”

I don’t know how Merce explained to Fonteyn. He and I never discussed it again. I always wondered if the decision had been Merce’s or John’s.

AM16. One of the great features of Cunningham's own dancing, and of the roles he made for others, was its quality of privacy. Even when several people shared the stage, and often even in a duet, they remained soloists - loners, one might say. Was this quality of privacy something to which you responded?

JJ16. Yes.

AM17. Cunningham himself ranged as a dancer from the animal to the urbane. There are connections within his works, but often each premiere marked a great departure from his last work. When you were working with him, how did you respond to that changefulness, the need to reinvent himself?

JJ17. I did not think of reinvention but of the unfolding and exercise of an inner language.

AM18. In a very remarkable tribute in 1967, you said "Merce is my favorite artist in any field. Sometimes I'm pleased by the complexity of a work that I paint. By the fourth day I realize it's simple. Nothing Merce does is simple. Everything has a fascinating richness and multiplicity of direction." Do you remember how you came to notice the complexity of his work? Were you used to watching dance before you watched his choreography? What were your early experiences of it like?

JJ18. In this period my own development involved important formative changes. It seems pointless for me to attempt to give order to them.

This September (2021), I emailed Johns this further question. In October, he replied.

AM19. In 1971, John Cage said the following: “We have to take a Buddhist approach toward this business. We are all related and it was simply fortunate that we came together. My relationship with Jasper Johns is similar to my relationship with Cunningham and Tudor. That is to say, I don't understand him. My relationship to Rauschenberg is quite different, as if we were the same person. We do not have to explain things to one another. I can have conversations with either Tudor or Cunningham, or Johns, in which I remain puzzled by what they say, even after many years. I never know what any one of those three is going to say, whereas I can predict, but still enjoy, what Rauschenberg could say, because he, like me, is interested in constant changing."

(Interview with Alcides Lanza, 1971, quoted in Richard Kostelanetz's 1988 "Conversing with Cage".)

I'm fascinated by this, especially its implications for his relationship with Merce, but I'm not entirely surprised. Is there anything you'd like to add to, or subtract from, John's statement?

JJ19. I think that John made such a statement about himself and Bob Rauschenberg more than once. I never understood it.

@Alastair Macaulay 2021

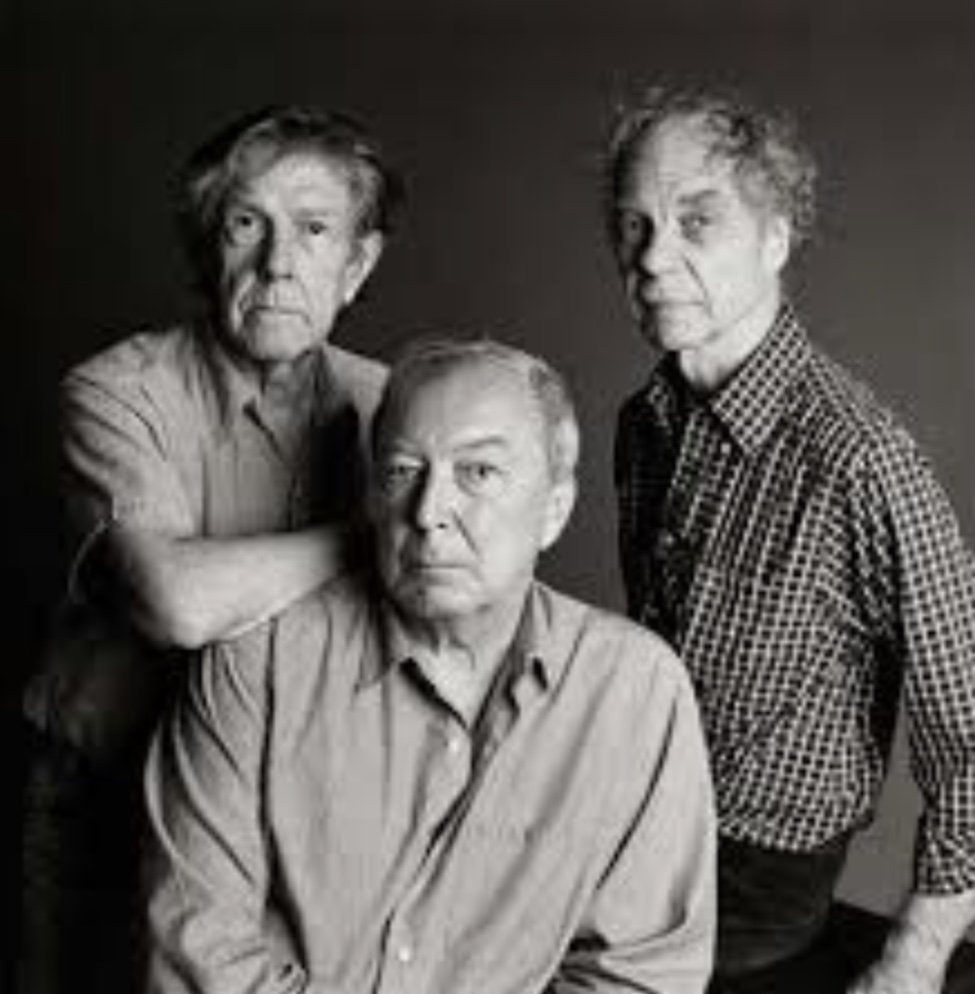

1: John Cage, Jasper Johns, Merce Cunningham. Photo: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders.

2: Jasper Johns (kneeling) adjusting or cutting Merce Cunningham’s costume for Cunningham’s “RainForest” (1968). Photo: Jim Klosty.

3: Jasper Johns spray-painting Carolyn Brown’s costume for Merce Cunningham’s “Canfield” (1969). Photo: Jim Klosty.

4: Dancers in Jasper Johns’s costumes for Merce Cunningham’s “RainForest” (1968), against Andy Warhol’s helium-filled “Silver Clouds” pillows

5: Merce Cunningham and dancers in Cunningham’s Exchange” (1978), with decor and costumes designed by Jasper Johns.

7: Jasper John’s “Numbers”, New York State Theater. Merce Cunningham‘s footprint may be seen on an upper right corner. Legend has it that Johns told Cunningham “I’ve got your foot through the door of that theater”, when the State Theater was new in 1964.

.

8. Two former colleagues of Cunningham before the Johns “Numbers” painting, February 2020, New York State Theater: Cunningham’s former dancer Catherine Kerr (left) and his former company manager Marleine Huffman. Cunningham‘s footprint can be clearly seen above them.

9: “Merce’s other foot”: a 2009 painting by Jasper Johns in which Cunningham, aged ninety, placed his footprint once more on a new Johns painting, this time shortly before his death in July that year.

10: Jasper Johns, “Dancers on a Plane” (1980-1981).

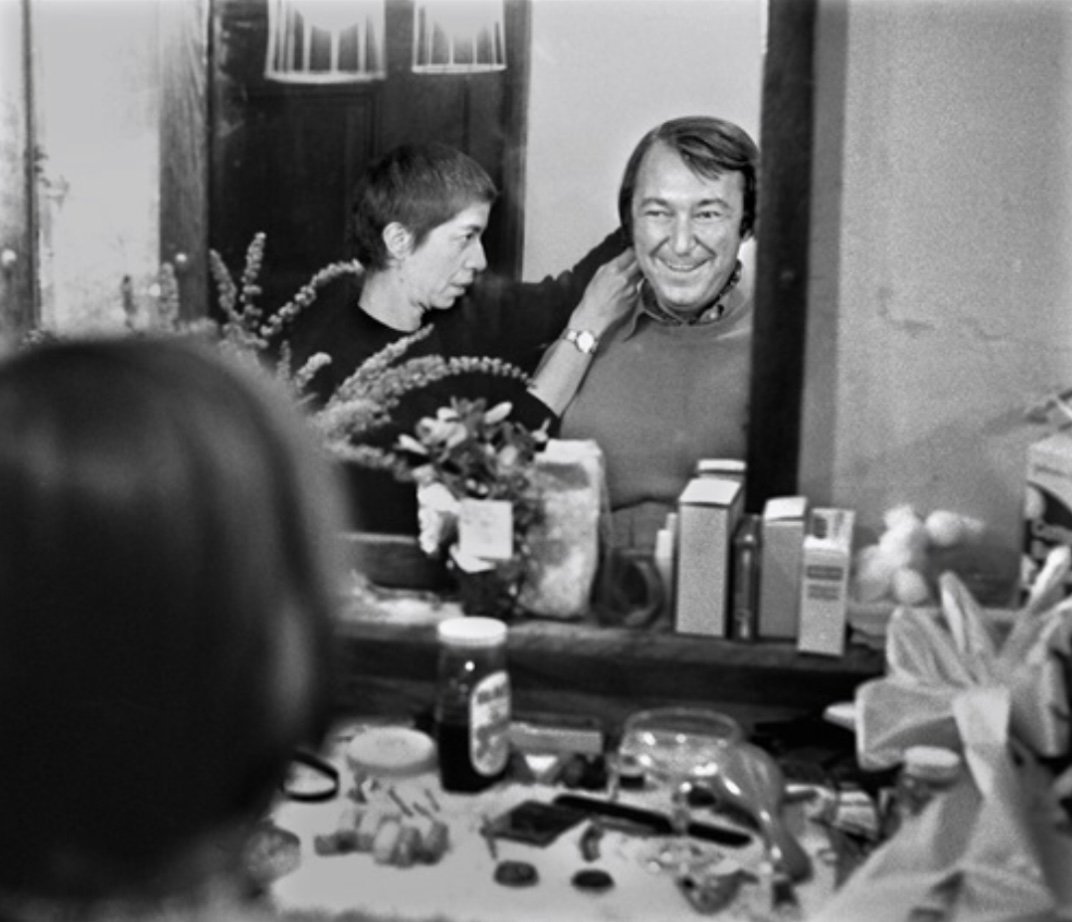

11: Viola Farber cutting Jasper Johns’s hair. Photo: Jim Klosty.

12: Jasper Johns, 2011. Photo: Jim Watson.