Galina Samsova (1937-2021) R.I.P.

The news of the death of the ballerina Galina Samsova (1937-2021) has just been announced by Christopher Hampson, artistic director and CEO of Scottish Ballet, a post she herself had held over twenty years ago. Though she was born in Volgograd/Stalingrad and trained in Kiev, she spent most of her career in the West, especially in Canada and in Britain. By the time I first saw her in 1976, when she was in her late thirties, she had starred with the National Ballet of Canada (also as a guest with New York City Ballet according to one source, though this is unconfirmed), and London Festival Ballet, but now was leading New London Ballet with her husband André Prokovsky; it danced at Cambridge’s Arts Theatre in my final term as an undergraduate, when I was newly hungry for ballet.

She had wide and prominent cheekbones that were striking even by Russian standards; her eyes were wide-spaced too. The muscles of her calves were emphatic; her looks were neither for body fascists nor for prettiness addicts. In everything I saw her dance, she had the incisive authority and space-consuming flair that epitomised the word “ballerina” in its secondary, Russian, prima meaning. She had many of the best Soviet qualities: the impetuous ardour with which to make “Spring Waters” exhilarating, expressive plasticity, tremendous largesse of gesture and line. Even while you were observing Natalia Makarova, Monica Mason, Merle Park, and Lynn Seymour in their primes, to see Galina Samsova in hers was to have a vision of heroic rapture. Although she could play ingenue roles with touchingly dewy naivety, her dancing was marvellously adult: she knew who she was, she staked large claims on space, and she was in magisterial possession of time.

In the years that followed (1976-1986), I saw her often with the touring Royal Ballet as it became re-named Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet (and a few times as a guest artist with the Covent Garden company: I saw her dance Giselle, Aurora, Odette-Odile, Raymonda (Act Three), Les Sylphides, Lise in Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée, the Elder Sister in MacMillan’s Las Hermanas, the title role in his Isadora, and many other roles. One of her peak achievements was in staging the grand pas from Marius Petipa’s Paquita in 1980, dancing the prima role herself (covering the Covent Garden stage in a powerful, brisk diagonal of grands jetés in her early forties) but also coaching three other ballerinas (Margaret Barbieri, Marion Tait, Sherilyn Kennedy were first cast) in other variations, so that they showed a fabulous variety of intensely stylish quality, and thereby bringing the whole company to a new high of classical style. Of her Carabosse in Peter Wright’s misbegotten Sleeping Beauty (1986), let us not speak just now: it would be wrong to blame her: at least it had great dignity. She also assisted Wright in his misguided Swan Lake (1981), a production that changed poor Tchaikovsky’s score more than usual while managing to suppress Ashton’s Swan Lake dances while restoring Gorsky’s. For her, Kenneth MacMillan created a lead role in his Verdi Quartet (1982), showing the stretch and sweep of her style. Lynn Seymour and she were friends; in Seymour’s Intimate Letters (1978) to Janácek’s score, Samsova created the central role, finely catching adult, conflicted emotions within a complex, subtle situation.

She herself, wonderfully spacious in style with the most flexible back I have ever seen in live performance, was a source of fascination. She divided opinions, leaving some people cold while moving others greatly. As I remember, there were roles were she moved me, others where I was left cold. But a constantly remarkable feature was how much less obtrusive her wrists and fingers were than any other Soviet Russian ballerina’s: in accordance with several old Russian dancers and most British ones, she made her hands subordinate to line rather than making them ornamental.

It always impressed me that she, a virtuoso who could eat up space and radiate with heroic Russian amplitude, was often at her most marvellous in moments of touching intimacy. The first time I ever found tears filling my eyes at a dance performance - in April 1977, when I was twenty one - was when she first danced Ashton’s Lise, seemingly an alien role for her. She caught the role’s speed and lightness, but she gave it moments of quiet gentleness like no other Lise I’ve seen. In particular, in the farmyard “ribbon” pas de deux with Desmond Kelly as Colas, there was a sequence when he played horse to her driver, with her tenderly cracking the “reins” (ribbons). Suddenly he turned to face her. She was gazing into his eyes with all the dewy lovelorn seriousness that young love can and should have: she gave that fleeting moment such unprecedented depth that, amid a ballet I had already loved with six other ballerinas, my eyes at once flooded. Three months later, in a summer in which I had seen and marvelled at four of the world’s most eminent Giselles (Natalia Makarova, Eva Evdokimova, Cynthia Gregory, Gelsey Kirkland) dancing the role at their peak in London, I saw Samsova’s first Giselle with Sadler’s Wells Royal at the Big Top in Cambridge; she played the mad scene with a poignant absorption, perfect focus, and absolute simplicity that not only moved me more than those more renowned stars but also (I later heard) so amazed her Sadler’s Wells colleagues that they slowly burst into amazed applause after the Act One curtain had fallen. As I remember, I saw her play the role four times with that company; in the second one, her Act One was no less definitive, simple, and moving, but, in her third and fourth performances, her second act took off to new peaks of ethereality.

She never showed off the suppleness of her back as some Harriet Hoctor stunt. And yet in autumn 1976, dancing with Prokovsky in a number he had arranged to Fauré’s Cinq Mélodies de Venise, I remember a moment when she approached his outstretched arm and, in a quick breath, on point, softly arched back over it until her shoulders were astoundingly close to her knees; she then unfolded back to the vertical just as quickly. In that April 1977 first Fille mal gardée of hers, she arched back in arabesque in the wedding pas de deux, with Desmond Kelly (always a superlative and handsome partner) so that, again, her shoulders were, just for an instant, unimaginably close to the knee of her raised leg. In those third and fourth Sadler’s Wells Royal Giselle performances, she not only held a glorious arch above Kelly/Albrecht’s head in the “Bolshoi” overhead lifts, she - unique in my experience - went on arching, her upper body and legs stretching further upward into the air above.

Even if you already knew and loved the glamorous grandeur with which the Sadler’s Wells company danced Rudolf Nureyev’s production of Raymonda Act Three, it was a thrill to behold the quietly majestic amplitude of her style: a form of grave tranquillity. Her épaulement and port de bras were wonderfully outstretched; and her authority had none of the exaggerated hauteur (“Brie under the nostrils”) that many British dancers think appropriate to aristocratic or royal roles.

She directed Scottish Ballet between 1991 and 1997; from the little I saw of the company then, I could discern a mind that was leading her dancers towards further eloquence, nuance, and subtlety. I never met her, but I never heard any dancer speak of her without affectionate admiration and gratitude. A mutual friend in 2019 encouraged me to visit her and to converse: you rightly imagine that I wish now I had done so.

Sunday 12 December

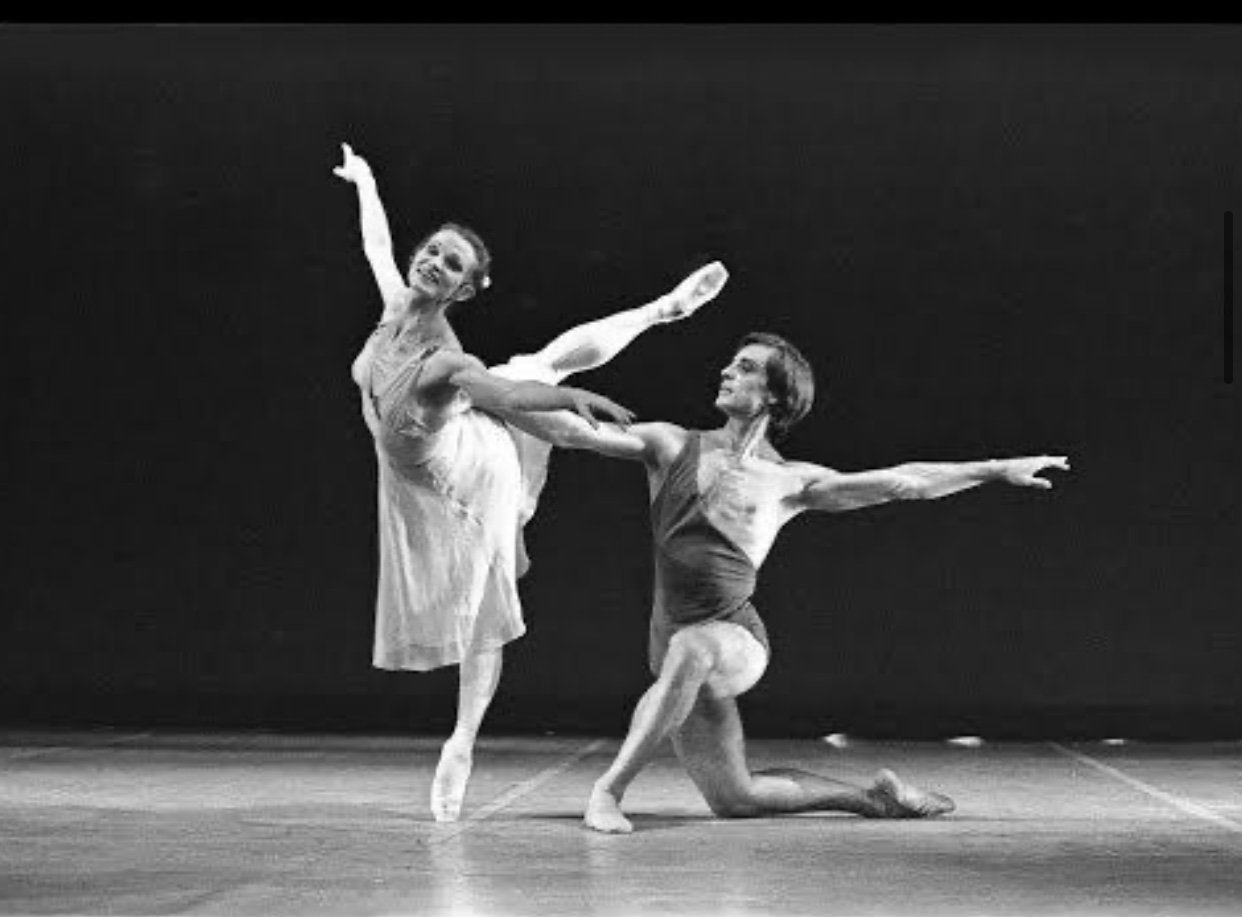

1. Galina Samsova with Desmond Kelly in the Soviet number “Spring Waters”.

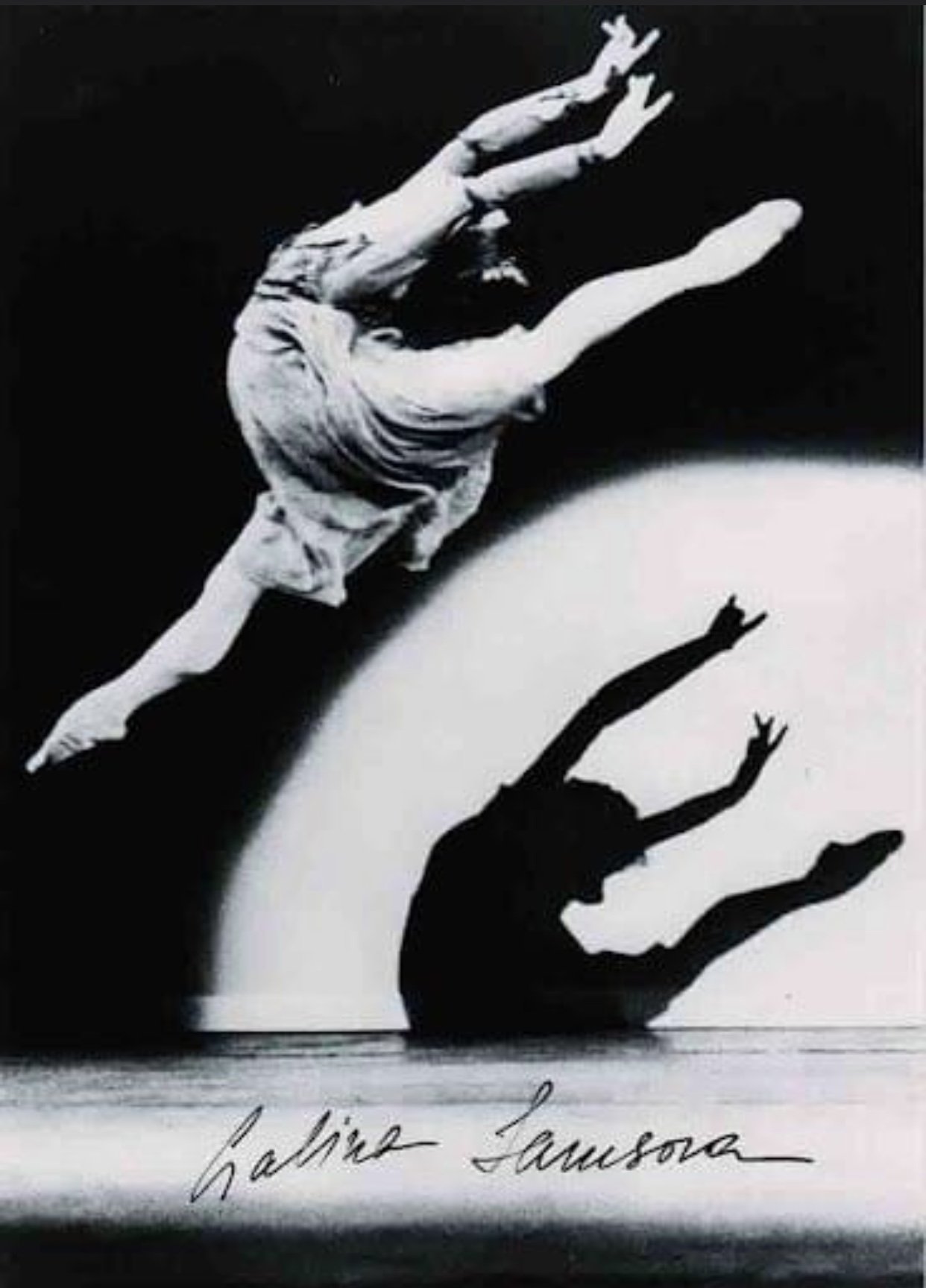

Photographs show Samsova’s impressive blend of Russian physical grandeur with unmannered and unobtrusive wrists, fingers, and arms; but I know no photographs that show how singularly touching she could be.

2. Galina Samsova as Juliet with the National Ballet of Canada, presumably in John Cranko’s production of “Romeo and Juliet”. This photograph shows the ardour and spaciousness that were constants of her style.

3. This signed photograph shows the plasticity of her back. But to see how she could achieve the same arching line meltingly, without bravura emphasis, in either supported arabesque or over the arm of her partner - this was breathtaking. My thanks to Janice Adelson for finding this photograph.