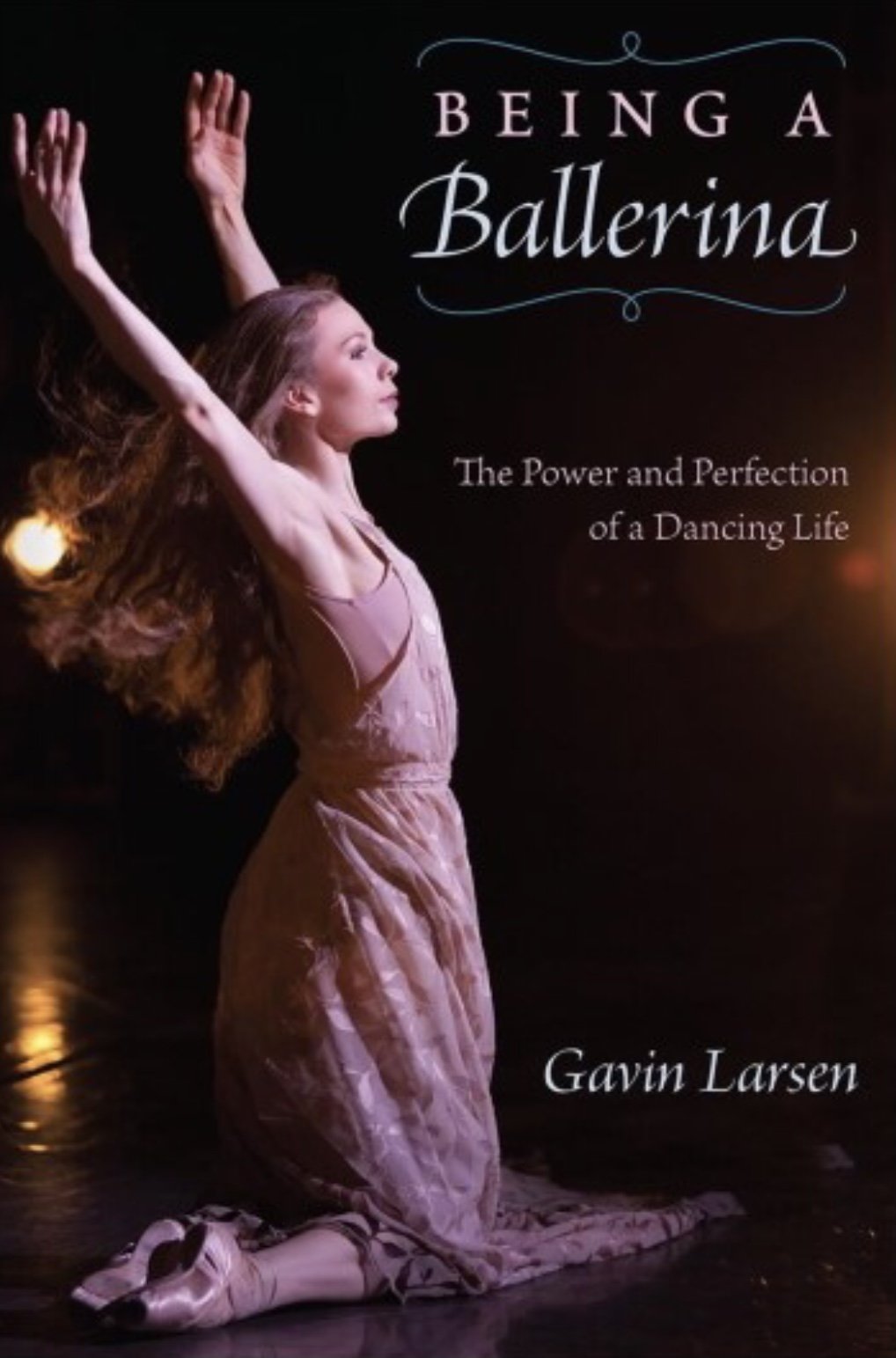

Ballerina Autobiographies, Georgina Pazcoguin’s “Swan Dive”, and Gavin Larsen’s “Being a Ballerina”

I.

Ballerina autobiographies are largely a genre of the last hundred years. True, it seems that Marie Taglioni (1804-1884), the epoch-making ballerina of the Romantic ballet, wrote some memoirs, but they were only published in 2018. [1] Perhaps there were other ballerinas who, before the First World War, sat down to tell their tales in writing; I hope so. But that war and the Russian Revolution changed world history and dance history – and the twentieth century changed women’s history, giving voices to women as seldom before. Suddenly, as the West became home to great Russian dancers who would never return to the country that had trained them to greatness, a number of Russian women dancers began to realise they had witnessed seismic changes of many kinds. They had tales to tell - not least tales of the changed status of women – and they told them.

By some stroke of fate, two ballerinas who had been close friends in ballet school in St Petersburg and who both made their homes in London, published their memoirs in 1929 and 1930: Lydia Kyasht (1885-1959) with Romantic Recollections (1929) and Tamara Karsavina with Theatre Street (1930). Karsavina’s became immediately famous, but there are no fewer fascinations in Kyasht’s. Though she’s only in her forties when writing, she’s well aware she’s describing a bygone world. One chapter - titled “Grand Dukes I Have Known” - begins:

“It might appear to an outsider as if the Russian Grand Dukes spent most of their time in making love, and in being made love to, but one must take into consideration the fundamental fact that Russian men love differently from Englishmen, and that besides being more ardent, they regard love-making as an important part, if not the main-spring, of their life.” [2]

Now read on!

Once Karsavina’s book had charmed the world, Russian ballerinas from generations before hers now produced their life stories. Later in the 1930s, Ekaterina Vazem (1848-1937) - the original Nikiya of Marius Petipa‘s La Bayadère (1877) and a teacher of Anna Pavlova - wrote Memoirs of a Ballerina of the St Petersburg Bolshoi Theatre 1867-1884. (Or rather, in her old age, her son compiled them.) In 1960, the ballerina Mathilde Kschessinskaya (1872-1971), under her Western name of Kschessinska, published Souvenirs de la Kschessinska (published in English in Arnold Haskell’s translation as Dancing in Petersburg). These are women not just aware of their places in history but determined to tell it differently. Both have scores to settle with Marius Petipa. And as for Grand Dukes – no ballerina can equal Kschessinskaya when it comes to recording grand-ducal offstage achievements and generosity.

II.

But how do you define ballerina? In its original Italian, it simply means “a woman who dances.” To Italians, Isadora Duncan and Martha Graham were ballerinas; and so is the least female dancer in any dance school. It was the Russians, with their essentially provincial misunderstanding of many Western terms, who doused the word “ballerina” with exalted mystique. They then blundered worse with the term “prima ballerina assoluta.” In Italian, a prima ballerina assoluta is simply a principal dancer: Virginia Zucchi was appointed the second of two prime ballerine assolute to the company of Reggio Emilia soon after her sixteenth birthday. The Russians, however, fetishized the “assoluta” label to quasi-sovereign status. You have not known the full nonsense of balletomania until you have heard or read someone announce, with grand authority, that this interpreter of leading roles is “not a ballerina” or that that veteran international star was “never an assoluta”.

Unfortunately for nomenclature, non-Italians have dominated ballet for more than a century. Across the world, “ballerina” is widely used in its non-Italian sense: I confess that, occasionally, I still use it that way myself. Should we include the memoirs of Bronislava Nijinska, Lydia Sokolova, Ninette de Valois, Agnes de Mille among the genre of ballerina memoirs? We know Nijinska primarily as a choreographer and as sister to her legendary brother Vaslav, de Mille almost entirely as a choreographer. Sokolova, though she danced leading roles, did not specialise in the more classical ones that, for many, are those by which to know the true ballerina. De Valois, though she was a noted Swanilda in Coppélia, is chiefly famed as a director and choreographer. Theirs are nonetheless marvellous autobiographies. (De Valois wrote three.) Those of Nijinska and Sokolova are strong contenders for the greatest ballet memoirs of all.

What’s a ballerina? The question receives different answers from two of this year’s American dance memoirists, Gavin Larsen (Being a Ballerina, University of Florida Press) and Georgina Pazcoguin (Swan Dive – the Making of a Rogue Ballerina, Henry Holt and Company). (I write before reading the autobiographies of Leanne Benjamin and Megan Fairchild.) Many of today’s dance-goers will have heard of neither Larsen, who was a principal of Oregon Ballet Theatre before retiring from the stage in 2010, nor Pazcoguin, who is a soloist with New York City Ballet. These women do both know they’re ballerinas – but in different ways and for different reasons. For Larsen, ballerinadom was the goal she eventually attained:

“There are dancers, and there are ballerinas.

“Just like there are cooks, and then there are chefs.

“The first time a dancer, a woman, is called a ballerina may or may not be a defining moment. It depends on who has done the calling. It may be flattering or give a tickle of excitement or an ego boost, but the dancer herself knows already if she is a ballerina or not. She may not think that she knows, but she does. And if she thinks she can become one, if she feels that there is something greater in her that has not yet flourished, being prematurely called ‘ballerina’ can be a little empty. The word’s honor will have lost some luster.” [3]

Larsen knows whereof she speaks. She has danced the Sugarplum Fairy, Juliet, Aurora, the lead role in Allegro Brillante.

Pazcoguin has danced none of those roles, but that doesn’t stop her from being a ballerina. For her, in the cafeteria at Lincoln Center’s Rose Building, “Ballerinas are absolutely everywhere”; and in the vision scene of The Sleeping Beauty “the Prince thinks he sees Aurora, but no! It’s just a bunch of ballerinas dressed in the same princess-style costumes!” (p. 119). After all, she announces, “I am a ballerina of twenty years.” (p.134), “an honest-to-God professional ballerina” (p.107), “a full-fledged ballerina” (p. 112).

What she means by this, it turns out, is that - in 2003, less than twenty years ago - she became a ballerina as soon as Peter Martins gave her a job with New York City Ballet. So what if she hasn’t actually had a career of the twenty years as she claims on p.134? “I’ve been with the company for nearly twenty years, which is about a billion in ballerina years.” (p. 126). So what if she’s never made it to principal status? For Pazcoguin, being a ballerina means having a corps contract. And now, she tells us, “Most people get quiet for a second when they learn I’m a ballerina with the New York City Ballet.” (p.90) (Discuss.)

III.

Over the last ninety years, the ballerina–memoir list has grown long. It includes those by Tamara Geva (Split Seconds, 1972), Alexandra Danilova (Choura, 1986), Alicia Markova, who wrote two (Giselle and I, 1961; Markova Remembers, 1986), Yvette Chauviré, another repeat-memoirist (Je suis ballerine, 1960 and Yvette Chauviré, Autobiographie, 1997), Vera Zorina (Zorina, 1986), Irina Baronova (Irina, 2005), Margot Fonteyn (Autobiography, 1975), Tamara Tchinarova Finch (Dancing into the Unknown: My Life in the Ballets Russes and Beyond, 2007), Maria Tallchief (America’s Prima Ballerina, 1987), Maya Plisetskaya (I, Maya Plisetskaya, 2001), Beryl Grey (For the Love of Dance, 1987), Elaine Fifield (In My Shoes, 1961), Carla Fracci (Passo Dopo Passo – La Mia Storia, 2013), Allegra Kent (Once a Dancer, 1996), Lynn Seymour (Lynn, 1984), Suzanne Farrell (Holding onto the Air, 1990), Marguerite Porter (Ballerina: A Dancer’s Life, 1987), Gelsey Kirkland (Dancing on my Grave, 1986; The Shape of Love, 1990), Merrill Ashley (Dancing for Balanchine, 1984), Darcey Bussell (Life in Dance, 1998; Evolved, 2018), Jenifer Ringer (Dancing Through It: My Journey in the Ballet, 2014), Misty Copeland (Life in Motion: An Unlikely Ballerina, 2014), and doubtless more. No, I have not read all the above.

All these women address various tensions between their dance lives and their offstage lives. Most of them are aware of the sacrifices made during their childhoods to give them a career. In several important cases, the ballerina’s relationship with her mother has been crucial. As the daughter becomes the mother’s wish-fulfilment, the parents’ marriage does not survive the strain.

Strange as it may seem, many ballerinas fulfil their talent in their teens. Before she was twenty, Baronova had created leading roles for Mikhail Fokine, Leonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska, and George Balanchine; she had starred on both sides of the Atlantic. Farrell created a three-act role for Balanchine at the age of nineteen, Bussell created one for Kenneth MacMillan at age twenty. By age twenty, Fonteyn was dancing the three-act roles of both Aurora (The Sleeping Beauty) and Odette-Odile (Swan Lake), exceptional in their high-exposure demands on stamina, style, and technique.

Yet there’s no formula to ballerina lives. Tamara Tchinarova Finch was born in the same year as Baronova, Toumanova, and Fonteyn - 1919. She, Tchinarova, was Baronova’s lifelong friend, but her ascent to leading-lady status was gradual. After dancing with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo for much of the 1930s, she became a prima of the Borovansky Ballet (with which her dancing was admired by the critic Arnold Haskell, who was well acquainted with her repertory). She was elegant, discerning, intelligent. Yet the dance parts of her memoir pale beside those about her early childhood and the end of her marriage. The two most haunting ingredients of her book are the howling of wolves in her Bessarabian childhood and the torments she suffered as she lost her husband, actor Peter Finch, to the sometimes cruel Vivien Leigh.

Both she and Baronova wrote memoirs that suggest that, by retiring in their thirties to become mothers, they had left dance behind. Yet this wasn’t so. Although I loved their books, I wish they had ended them differently, with their returns to the dance world. Baronova often worked for the Royal Academy of Dance, while Tamara Finch (as many of us knew her), who had had a rich life as a professional translator after leaving the stage, contributed to Dancing Times and translated for visiting Russian ballet companies. You won’t find my favourite Tamara Finch story in her book. In 1986, she (in her sixties) translated for Galina Ulanova when the great Soviet ballerina (in her seventies), returning with the Bolshoi to Covent Garden, spoke at a press conference; it was touching to see the immense respect Tamara had for her. (She translated Ulanova’s words about how important the Bolshoi’s 1956 season at Covent Garden had been for her. “As we say in Russian, the house at first was so quiet, you could have heard a fly fly.”) Afterwards, Tamara (as she told me) asked Ulanova if she could help her in any way. Ulanova said quietly that she would love to see her former dressing room. Tamara, only too happy to oblige, took her backstage; they managed to find it together. Tamara, relating the story, added, “What I did not tell Galina was that, twenty years before her time there, it had been my dressing room, too.”

At the other end of the spectrum is Merrill Ashley’s Dancing for Balanchine. Although Ashley shows she’s well aware that there’s a world offstage (her conversations with her husband form a telling part of her book, and her initial embarrassment in befriending Balanchine is vividly recounted), nothing is more thrilling here than her ultra-detailed parsing of the fundamentals of technique – of Balanchine technique, in particular. Battement tendu, rond de jambe à terre, passé relevé, pas de chat, petit jeté: the loving scrutiny with which Ashley scrutinises these recaptures the gleaming fastidiousness of her dancing onstage.

IV.

An existential question arises for many of these women as they write: “Am I in life the same as the woman who dances?” My own favourite here is always Fonteyn, who is both funny and philosophical about the process of becoming “Margot Fonteyn” (the stage name she took in her mid-teens) and what it sometimes cost. It’s worth having both the original hardback edition of her book (just for its endpapers, a marvellous Victorian cartoon showing two aspects of the ballerina life: “Coming Out in the Limelight” and “Going Home in the Rain”) and the 1989 second edition, in which she covers the years 1975-1988, ending not long before her death in 1991.)

In her early twenties, Fonteyn danced a punishing schedule through the Second World War. Sometimes she performed Giselle or Aurora twice in a day, sometimes she danced Odette-Odile while the theatre and audience was being shaken by bombs falling nearby:

“With the ending of the war, exhaustion and a ‘restricted diet’ together left me quite ill for a while. An infection on my face threatened to leave a nasty scar, and the specialist treating me, Dr Isaac Muende, was so deeply concerned about this that he tried to try a completely new technique. He injected the recently discovered penicillin directly into the point of infection which, to his delight, healed up without a trace. Seeing him so worried about the scar, I said lightly, ‘Oh my feet are far more important than my face.’ I think he took this as a kind of reproof, not believing I was so silly as to mean it. He treated me as delicately as a film star, never realising being the only thing that mattered to me, I attached no importance to any blemish that would be invisible at a distance.” [4]

Describing her life in the early 1950s, when transatlantic tours made her an international sensation, she writes:

“Probably my technical accomplishment as a ballerina was now at its peak, for I had been working very hard to eradicate faults acquired during the crowded war years. If anything I gave too much attention to that aspect and several critics found me cold. I am sure they were right, because there was so little of myself left in the Margot Fonteyn they saw. The created image was in danger of taking over. In retrospect, I can see that I had reached the farthest part in the great arc of my life, and was out in the emotional wastelands of some fallacious person who was yet, in some ways, also me.” [5]

In 1953, she was offstage for five months absence with diphtheria, which for a period paralysed both her feet and tongue. On her return to dance at Covent Garden, she was greeted with an overwhelming ovation – tears were seen to pour down the face of David Webster, that theatre’s director – which expressed how vital she was to her audience and colleagues.

“Flowers spread across the sixty-foot width of the stage. Clearly the welcome was by way of a special message of affection for me, not related to my dancing ability that night. It was a strange, almost weird feeling to realise that I, or Margot Fonteyn – or perhaps both - was – or were – the object of that flood-tide of emotion.” [6]

Later that year, Roberto (“Tito”) de Arias - beloved boyfriend of her late teens, now married with three children and much fatter - returned to her life after fourteen years, sweeping her off her feet with flowers, a limousine, and expensive suppers.

“‘You are going to marry me, and be very happy.’ Tito said as he nonchalantly handed me a little packet containing a beautifully simple diamond bracelet. Margot Fonteyn, ballerina, thought ‘How marvellous! This is the way ballerinas should live!’ But I was quite upset. I don’t like divorce and I believe it sinful to take another woman’s husband. I remonstrated with Tito, begging him to go away, to stay with his family. He want to Panama, but was back in a week, noticeably thinner and happier. [7]

“Meanwhile, Margot Fonteyn had kept the diamond bracelet.”

V.

Larsen and Pazcoguin are very different women with very parallel lives. Both were trained at the School of American Ballet; both refer to the same teachers. Both women name Antonina Tumkovsky (“Tumey”) as the teacher whose classes give them some of the greatest challenges of their lives. Larsen graduated in 1992, joining the excellent Pacific Northwest Ballet for several years, and retiring from Oregon Ballet Theatre in 2010; Pazcoguin graduated in 2003, and is still dancing with New York City Ballet, not yet a soloist but currently rehearsing the Sugarplum Fairy in “The Nutcracker” (a ballet she scorns in no uncertain terms).

Many features of Pazcoguin’s story are remarkable. She is mixed-race (father from the Philippines, mother Italian), the only Asian-American woman soloist in the history of New York City Ballet, and almost invariably a fireball onstage. Since 2008, she has possessed, with singular flair, the singing-and-dancing role of Anita in Jerome Robbins’s West Side Story Suite (1995). Members of the New York ballet audience quickly referred to her as “Georgina” (or “Gina”). Although she remained in the corps for ten years, she was singled out by the company’s ballet-master-in-chief Peter Martins to create two principal roles: the Nurse in his full-length Romeo and Juliet (2007) and Scala in his Ocean’s Kingdom (2011). She made singular impressions not just in acting roles (Carabosse in The Sleeping Beauty) and solo variations but also in often anonymous demi-soloist roles: I can still see the way she attacked steps as one of five women in black leotards in Balanchine’s Symphony in Three Movements, burning up space and time. She had an operation to remove fat from her thighs, to conform better with the company’s ideals of body shape. Several years after joining the company, she had an affair with the principal dancer Charles Askegard, making the headlines in 2011 when his wife of ten years, the celebrity author Candace Bushnell, named her in divorce proceedings.

Pazcoguin’s career was not damaged by this. She was promoted to soloist rank in 2013. Since then, she has taken time away from City Ballet to appear in Broadway productions of both On the Town and Cats. Before her time in Cats (2016-2017), she was cast as the super-fast Dewdrop in the Balanchine Nutcracker and the Amazonian tornado Hippolyta in his two-act Midsummer Night’s Dream, both of which she played with unusually and excitingly powerful impetus. Although most of us can understand why she spent months on Broadway, it took its toll of her ballet prowess when she returned to the fold. She then suffered a serious injury. When she returned to the role of Dewdrop in 2018, she showed little of the marvellous oomph of three years before.

Even so, the real Pazcoguin is a far more complex and interesting creature than she yet knows how to show offstage. On the page, she is shrill, incoherent, foolish, vulgar, passionately drawn to clichés, and attention-grabbing. “I am one hella graceful diver!” she announces in Swan Dive (p.109). Grace, however, is not the characteristic of her Swan Dive prose. “I dug all of this shit, and it absolutely blew all my four-year-old mind.” (p.23) “You don’t fucking miss class” (p. 126) - though she later tells of having missed class. “When a dancer doesn’t get cast in a role they’ve devoted time and energy into rehearsing, they tend to feel pretty effing shitty and rejected.” (p.137). “Because shit really does always go down at the ballet, I always say!” (p.138). “This is my asshole take… Someone always gets fucked.” (p. 139). “Motherfucker-fucking-fuck” (p. 140). “UMMMMM EEK and WHOOPS!” (p.194) Curiously, if you listen to Pazcoguin talking about her book in interviews, she sounds far more intelligent and deploys a far wider vocabulary than she does in its pages.

On p. 37, she applies “shock and awe” to the dancing of her classmates. On p.39, she homes in on the “shock-and-awe reaction” of the churchgoers when, during her schooldays in Pennsylvania, she falls over in the aisle of her Catholic school’s church: “my legs every which way and my Catholic uniform skirt in a very immodest mess… Wow, how did I manage to pull focus from Jesus?” (You can’t help feeling that Paczcoguin has been figuring out how to pull focus from Jesus and any other unfortunates ever since.)

She loves shooting her mouth off without checking. “Remove the spirit of the corps from a Balanchine production and what you’ll get is bravura without context.” (p.59) Oh yes? Try removing the corps from Apollo (1928), Prodigal Son (1929), Meditation (1963), Duo Concertant (1972), Sonatine (1975), and any other Balanchine pas de deux), Balanchine’s various ballerina solos (the 1975 Pavane and the 1982 Élégie have both been danced this century) or the 1981 Mozartiana. Her account of the famous genesis of Balanchine’s Serenade (p.61) is the most slapdash I have yet encountered. (She can’t even be bothered to check what Balanchine himself wrote about it.) About The Nutcracker, she proclaims “The U.S is the only country that regularly performs a ballet that everyone else in the world considers unwatchable” (p.174) when a quick google could have taught her that the London routinely fields a minimum of two Nutcrackers per annum; this year, the Royal Baller at Covent Garden is presenting its wrongs-headed production thirty-one times. On goes Pazcoguin:

“Dogs? Love them. Food? Sometimes it’s better than sex, if I’m being brutally honest. And people? The jury is still out on whether I qualify as a people person.”[8] The degree of brash self-absorption in those sentences is startling.

Pazcoguin works hard to entertain. There are many more fucks and shits than I have quoted above; she evidently means them to impress. She regales us, at length, with her jazzed-up versions of the twelve most ridiculous occasions on which she has fallen over in public. But, whereas the City Ballet principal Ashley Bouder used to Tweet about her not infrequent stage falls with laconic good humour, Pazcoguin laboriously builds each of her twelve tumbles up into long, dull, but naggingly boastful accounts. Here’s the one when she falls over in a Cats rehearsal:

“I AM WALKING. MY INSTRUCTIONS ARE TO WALK. But I go down so hard – my entire right side crashes onto the floor. Everyone here is an accomplished dancer, but I’m the only professional ballerina in the cast, and when asked to walk, I end up on the floor.

“And I’m also the only person who has total wiped out while walking in front of everyone, the entire creative team, the music director. Everyone is shocked. Legit shocked. I went down so effing hard that people are concerned, Oh my God is the ballerina okay?” [9]

Fonteyn writes of having fallen over in a performance, Suzanne Farrell has spoken in interview of falling over in Balanchine’s Diamonds, Merrill Ashley’s many falls are still remembered by many, Bouder joked of her tumbles, Larsen writes of hers, but so what? Pazcoguin is so over-emphatic that she sounds determined to annihilate every previous ballerina fall. Hence the title of her book.

Every so often, Pazcoguin rouses herself from her loud self-fascination to tell us that she is, guess what, an abuse victim. Principally, she tells us on page 3, she was abused by the man the ballet world loves to hate, Peter Martins, who ran New York City Ballet during her first fourteen years there. She then adds, though only in a footnote:

“To be clear, abuse comes in many forms: verbal, mental, and physical. I also want to be clear that my abuser did not hit me, Nothing I say in this book should be interpreted otherwise. The harm he has inflicted on me is psychological and its effect on me has been devastating.” [10]

The two main forms of abuse that Pazcoguin describes in Martins’s City Ballet are body-shaming and physical/sexual license. I wish she wrote about the body-shaming with a tenth of the precision she employs when she’s interviewed about the book: she’s much more focused and authoritative in the Conversation on Dance podcast [11] than anywhere in Swan Dive. The line of her legs was criticized until she chooses to pay $10,000 for an operation that removes fat from her thighs.

And the male dancer Amar Ramasar, according to her, habitually tweaked her nipples. Pazcoguin tells us - p.102 - how she responded: “he’d pinch my nipples and, rather than demanding he quit it, I’d respond by slapping his ass so hard that I’d leave a handprint.” How traumatised does she sound to you? (Others who worked with them both have told me they never observed any such tweaking anyway.) Ramasar’s behaviour, Pazcoguin makes clear, was part of a larger male-dominated culture: she laboriously tells of some inappropriate talk and behaviour by the ballet master Jean-Pierre Frohlich (her version is not accepted by other witnesses), and she makes sure we know her version of the photo-sharing scandal involving Chase Finlay, Ramasar, Zachary Catazaro, and Jared Longhitano. She goes further:

“In my experience at City Ballet, men of all sexual preferences have equally caused enough pain in their degradation of the female gender, intended or not. They say there are those who can only heal by paying the trauma and harm they’ve experienced forward, and that goes for everyone. I am well aware that there are a lot of individuals affiliated with City Ballet (and perhaps in the broader world) who are going to sting reading that assertion, but I don’t say it lightly or to overgeneralize. I say it because I think it’s a cultural issue at the ballet that often gets a pass, and it shouldn’t. For instance, in no circumstances is it appropriate for any person, colleague, ballet master, or patron to walk up to a ballerina who is standing up in the back of class, her arms protectively wrapped around her stomach, and make a joke, ‘What’s the matter? Are you pregnant?’ I can tell you from experience that what’s the matter is that she’s having a bad body day and confronting that day by staring at herself in a mirror. Applying corrections given on technique while comparing herself to the eighty other taller, thinner ballerinas in the room. Anyone with a beating heart can sometimes be a shitty human.” [12]

Pazcoguin’s basic point here is spot-on. Men in and around ballet have been routinely and hurtfully insensitive to women when it comes to matters of physique (other matters, too). You can’t help wishing Pazcoguin could make the point with fairness and with precision.

Yet her book is so incoherent that, if you read it carefully, she makes a bigger mess than she realizes. On the same page 3 where she names Martins as an abuser, she speaks of ballet master Rosemary Dunleavy: “Rosemary’s career as a ballet mistress began under Balanchine and continued with Peter – in other words, she’s dealt with some shit.” Even when you appreciate that Pazcoguin uses the word “shit” in many different circumstances, what on earth has prompted her to associate Balanchine in the same “shit” as Martins? Maybe she’s one of the people who feel Balanchine should be accused under the new #MeToo climate – and maybe he should - but Pazcoguin can’t be bothered to explain what she means. As she announces, “shit always goes down at the ballet,” And Pazcoguin is determined to spread shit far and wide.

She feels compelled to admit that Frohlich has always been on her side, casting her in the Robbins roles that he supervises. His inappropriate talk and behaviour were not directed at her, but she still feels he should apologise to her for her having witnessed them. She does not, however, feel she should thank him for having given her a series of big breaks in her career.

Just how devastating does Pazcoguin really feel Martins’s treatment of her has been? She admits that he singled her out to create two large roles while she was in the corps. Oh, and then he made her City Ballet’s first Asian American soloist. Oh, and he let her dance with American Dance Machine, which introduced her to Broadway choreography. Oh, and he gave her leave to appear in not one Broadway show but two, while telling her which lead Balanchine roles he was considering her for. Oh, and he established a climate where it was fine for her to respond to Ramasar’s nipple-tweaking by harshly slapping his (Ramasar’s) backside. Oh, and she meanwhile has made time to gain a real-estate license, thus preparing what may prove a lucrative second career. Oh, and she and Phil Chan began spearheading the “Final Bow for Yellowface” movement in 2017, influencing Martins and others to revise the makeup and gestures used in the Chinese Dance in The Nutcracker. Is this your idea of devastation? Well, it’s certainly Pazcoguin’s.

Martins, Frohlich, and others have gone out of their way to be good, at times, to Pazcoguin. Sure, some of those men are thoroughly flawed. I don’t miss Martins, who resigned on January 1, 2018 - and yet Pazcoguin’s book makes me more aware than before that he acknowledged her talent and often did her favours. Does she bother to mention the part that American Dance Machine played in transforming her career? Don’t even ask. It’s hard not to find her autobiography the biggest exercise in ballerina ingratitude since Gelsey Kirkland’s.

I’m aware that here I sound dangerously close to saying that Pazcoguin and other women should damn well be grateful for the breaks they received (and put up with the demeaning treatment they received). No, I don’t mean that or say that. But the Martins history needs a far more exact survey.

And Pazcoguin proves herself a thoroughly unreliable witness. Most strangely of all, she turns out to have been really close friends with Ramasar (pp.122-125), a late-night drinking companion with whom she and others could enjoy being outrageous, after three gimlets playing rounds of Fuck Marry Kill. She loves telling us how they enjoyed making Ramasar the loser.

But then, making Ramasar the loser has been, it seems, an ongoing project for Pazcoguin. She whopped him when he tweaked her nipples; she jeered when he lost at Fuck Marry Kill. (She relates how every round ended with “Kill Amar”.)

I don’t condone nipple-tweaking - and yet it’s hard to accept such tales when they come from someone who brags about having fun by imagining killing her male colleague and from falling over backwards from excess drinking. Over to Pazcoguin:

“…the next thing I knew I was flying through the air and then lying on the floor of the bar…. The bartender looked concerned, like maybe he shouldn’t have given me that last margarita.” [13]

Pazcoguin, however, climbs back onto her stool and goes on drinking. When she hung out with Ramasar in bouts of competitive drinking, he was the fall-guy. She relishes telling us how she and her pals laughed at his expense. I hadn’t thought of Ramasar as a victim until I read her book.

It’s objectionable that she, so keen to name and shame others, refrains from naming Candace Bushnell and Charles Askegard in her account of the breakup of their marriage, though she was cited by Bushnell and named in newspapers. Is this reticence or this hypocrisy? Pazcoguin:

“I fell in love with a fellow company member. While he made himself available to me, he was legally married to somebody else. My choices hurt people, and it’s something I will always be sorry about. I do not suggest following this path, even if your heart is screaming for you to follow it wherever it wants you to go. I would never do it again.” (p.205)

This brief no-names account might seem admirable did she not then make it a mere prelude to yet another of her raucous I-fell-over-onstage stories (“Swan Dive #10”). Amid her eagerness to celebrate her maladroit stage behavior here, she’s exceptionally graceless in failing to acknowledge the solicitude extended to her by ballet master Rosemary Dunleavy (and therefore by the Martins regime). Nobody fired her, nobody in the company gave her a telling-off, but instead the ballet master repeatedly showed kindness and concern. Does Pazcoguin express any thanks? Of course not! She’s far too keen to encourage you to find the video record of her stage tumble (“my falling-on-my-ass-as-a-result swan dive is featured in a reel of Nutcracker bloopers, available online for your viewing pleasure and to haunt me forever,” p. 206).

Pazcoguin, you see, isn’t really responsible. She’s been a victim all along:

“On January 1, 2018, seven months after allegations about Peter were brought to the forefront… seven months that I would describe as Requiem for a Dream-level fucked-up and traumatic, I was jolted awake by the realization that I am a victim.

“I am a survivor of some deep emotional abuse, and all of the behaviors I have exhibited prior to that moment, in my relationships with men, actually in ALL my relationships, came down to the abuse I started being exposed to at the age of seventeen. Stockholm syndrome is also very real, and the experience of coming out of it is excruciating. The shame and the brokenness that have been ingrained into my psyche largely by the power dynamic imposed upon me by this leader is something I will battle for years to come.” [14]

I think this means - among much else - that Peter Martins is to blame for Pazcoguin’s affair with Charles Askegard. Interesting.

Very possibly, Pazcoguin is indeed one of many female dancers across the ballet world who have reason to feel abused. (Conditions for women have been worse in some other companies, by the way. One artistic director of Martins’s generation used to boast in the company showers, the next day, of which ballerinas he had just beaten up and bruised before having had sex with them.) In recent years, the ballet world has begun changing, principally in terms of race, gender, sexuality, and sheer human respect.

Anyone who’s seen Pazcoguin dance knows that she has cause for pride – that she dances with the best kind of pride. That’s not how she writes, though. Instead she unwittingly portrays herself as more of a mess than she is. (Nobody reading this book could have any idea of the impetus and precision Pazcoguin shows as a classical dancer.) And she sounds most damaged when – much of the time – she insists she’s the life and soul of the party.

VI.

Ramasar was one of three male City Ballet principals named and shamed in the Alexandra Waterbury case. It’s shocking how little odium has been directed to Jared Longhitano, the donor who wrote the single most heinous line in all the much-published texts (of women dancers: “I bet we could tie some of them up and abuse them like farm animals”). Instead, Waterbury and others have tried to claim that it was Ramasar who was part of the “farm animal” exchange: he certainly wasn’t.

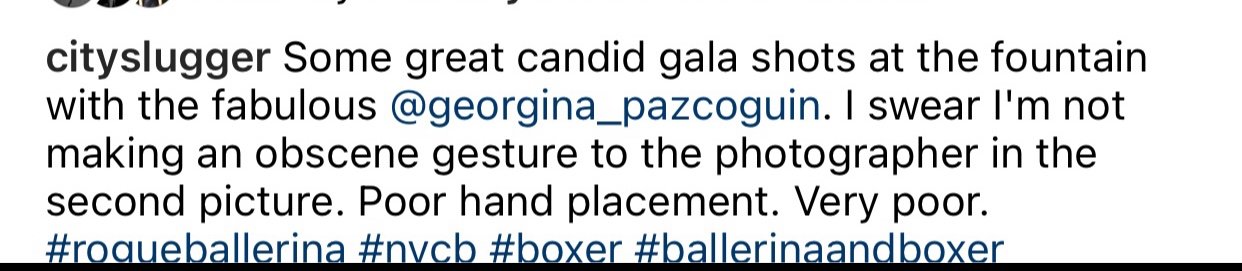

Why does Pazcoguin go easy on Longhitano? Perhaps because she’s been shown closely beside him in two photos he posted on Instagram. He, writing as “cityslugger,” mainly posts about boxing. On 2 October 2017, however, he posted a pair of pics (see illustrations 4 and 5) of “the fabulous @georgina_pazcoguin” beside him at the Lincoln Center fountain, while drawing attention to the way his hand gesture might be misconstrued as obscene. Actually, Pazcoguin seems to be sitting on his right hand, while his left hand is covering his groin. Longhitano:

“Some great candid gala shots at the fountain with the fabulous @georgina_pazcoguin. I swear I’m not making an obscene gesture to the photographer in the second picture. Poor hand placement. Very poor #rogueballerina #nycb #boxer #ballerinaandboxer.”

The next day (3 October 2017), he accompanied one hooded selfie (illustration 7) with these words:

“10 rounds nonstop on the heavy bag. 30 straight minutes of throwing punches with no rest at all followed by a 20 minute tempo ride in the bike. THIS is training. I don’t post videos of me working out because I’m too focused on demolishing my competition. I’m on this journey myself.”

A month earlier, he posted a photo of himself (illustration 9) with his gloved fist beside his face, with the words “I’ve retired more men than Social Security. Respect me or pay the consequences. Pick your poison: you get beat down or you get shot.”

Don’t you think his prose style resembles Pazcoguin’s? Yet in her book she mentions him only as “a young patron donor named Jared Longhitano”, as if she’d never encountered him in person, when recounting her version of the Alexandra Waterbury photo-sharing scandal.

Instead of denouncing the non-celebrity creep Longhitano, Pazcoguin and Waterbury are among those who have gone on attacking Ramasar. True, AGMA insisted that New York City Ballet should reinstate Ramasar as principal. True, the judge in the Alexandra Waterbury case dismissed charges against him. But “Let’s pick on Ramasar” seems to remain the name of the game. (Pazcoguin, p.124: “no one would want to fuck or marry Amar ever, no matter how hideous the other options.”) I hope it’s not relevant that Ramasar is City Ballet’s most eminent Asian American dancer this century.

I don’t doubt that Peter Martins allowed a number of heterosexual men (Ramasar included) to treat City Ballet as their sexual playground. Some of this behaviour may have begun with Balanchine, who – it’s likely – encouraged and licensed some straight male dancers to seduce a number of the company’s women.

Seduction alone is no crime, but, where power and influence become involved, we enter into difficult waters. This century, official regulations have been changed this century, not least around Lincoln Center, for a number of companies, covering the sex-power connection in impressive ways.

The 2018-2019 transition from Martins to his successors was slow. It may have seemed symbolic that a woman, Wendy Whelan, was eventually named as associate artistic director of City Ballet in February 2019 – but neither she nor artistic director Jonathan Stafford have made any proclamation to match the one made by principal dancer Teresa Reichlen on September 27, 2018. (Reichlen co-wrote it with Adrian Danchig-Waring.)

“Good evening.

“We the dancers of New York City Ballet want to take a moment to thank all of you for being here tonight at one of the most important evenings of our year.

“As dancers, we decided early in our lives to dedicate ourselves to this beautiful art form, many leaving family and friends as teenagers. Our teachers at the School of American Ballet led us through Balanchine’s teachings, and instilled in us a strong work ethic and a pursuit of excellence. Our teachers taught us to be proud and not settle for less than perfection.

“With the world changing – and our beloved institution in the spotlight – we continue to hold ourselves to the high moral standards that were instilled in us when we decided to become professional dancers.

“We strongly believe that a culture of equal respect for all can exist in our industry. We hold one another to the highest standards and push one another while still showing compassion and support.

“We will not put art before common decency or allow talent to sway our moral compass. NYCB dancers are standard bearers on the stage and we strive to carry that quality, purity and passion in all aspects of our lives.

“We want to be role models and create an inspiring environment in which future generations of girls and boys will have access to both the joys and responsibilities that we have as dancers of NYCB.

“Each of us standing here tonight is inspired by the values essential to our artform: dignity, integrity, and honor.

“And all of us in this magnificent theater share a love for dance, whether it is the physical act of performing, the nightly pleasure of watching, or both.

“We, the dancers of NYCB, want to take this moment to thank you for appreciating and supporting this Company. And thank you especially for your continued support at this time.

“We are proud of the work we do, and we are grateful for the opportunity – and the honor – to bring beauty into the lives of our audiences.” [15]

This speech was thrilling to hear at the time; it remains inspiring to read now. We should look on it as the moral turning-point for New York City Ballet; I’m sorry that Stafford and Whelan have never referred to it. And does Pazcoguin even mention it? You bet she doesn’t.

But it’s also worth observing L.P.Hartley’s line - “The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.” Yes, people behaved badly before Reichlen’s speech. We should judge them by our modern standards as well as by the standards of their day. But now we move forward. And if we spend time thinking about Ramasar, Longhitano, Finlay, Catazaro, we can see that they, too, were victims. Pazcoguin uses the modern cliché “toxic masculinity”: it’s worth establishing that such masculinity is toxic to the men who need to display it as well as to those women and men who are scathed by it. I wish I did not find Pazcoguin desperate to make her own personality seem toxic too.

VII.

The psychopathology of ballerinadom is complex. Fonteyn, with her rich sense of humour, speaks of herself at a few moments in the third person singular (“Margot Fonteyn, ballerina”) as well as in the first. But Larsen, in Becoming a Ballerina, moves immediately into a form of multiple personality syndrome. Part One Chapter 1 (“The Eight-Year-Old, Part 1”) alternates between first and third persons singular , but with Chapter 2 (“How to Be a Ballerina, Part 1”) we’re also off into the second person singular:

“Get out of bed gingerly. As soon as your feet touch the floor, even before hauling yourself upright, carefully test your back for spasms: to do this, flop face forward over your mattress, legs hanging over the side to make an L-shape with your body. Stretch your arms our across the bedsheet, feeling its softness against your cheek, and pause. This is only the first of many moments today when you’ll try to imagine what’s deep under your skin, listening hard enough to hear the inner mechanisms and your muscles and bones. The always audible pops and cracks are meaningless noise and crackle. Once your spine has unkinked, move immediately to a very hot shower.” [16]

What age are we/you/she supposed to be now? Are we/you/she still eight?

“…I’ve always known who I am. Spending my time wrapped up in dance and all the peripheral things that it required did not hide me from myself.

“But now, when I look back in time, what I wonder is just who, exactly that dancer-person was. I’m in awe and even disbelief, sometimes, that she and I are the same being. My dancer-self really does feel like a “she,” another person inside me, like a Russian nesting doll, uncovered then, but now sheathed in an outside layer that looks exactly the same but is just a shell.

“The further I look back through the years, the more removed I feel from that person…” [17]

By the time we’ve reached Chapter 11, when “her father” changes identity to become “Dad”, we’re growing deeply disoriented. Yet this, at some strange level, is part of the intention: Larsen the ballerina is a composite personality, aware of the self she watches in the mirror, aware of the alchemy she achieves with music, aware of herself as child and student and colleague.

And if you haven’t heard of Gavin Larsen, that, too, is part of her plan. This is something of a self-help book. It’s not quite “You too can be a ballerina”; instead it’s “This is what’s involved for any of us who find we are made of the right ingredients and who stay the course.”

Unlike Pazcoguin, Larsen has not been criticised for physical imperfections – and yet Larsen, unlike Pazcoguin, was not invited by Peter Martins to join New York City Ballet. Larsen instead succeeded in joining another of America’s finest companies, also Balanchine-based, Pacific Northwest Ballet. Yet there came a moment when this young woman, though so much less assertive than Pazcoguin, had to acknowledge that her talent was going unappreciated by those that ran Pacific Northwest. She upped and left; she freelanced; she joined Alberta Ballet. Finally, she found Oregon Ballet Theatre, then run by Christopher Stowell, the son of the couple who had failed to appreciate her at Pacific Northwest. There, paradoxically, she fulfilled her potential: she became a ballerina.

Each of the short chapters of her book is a step in this ballerina Gradus Ad Parnassum – sometimes an apparent step backward. Like Pazcoguin and other dancers of recent years, Larsen records the pain involved in dancing, but I’ve never read a more harrowing account of a ballet dancer’s physical pains than hers of her first period with Pacific Northwest Ballet.

“Up until this point, I’d never worn pointe shoes for more than three hours at a time, but now I was called to rehearse for six hours a day – after the hour-and-a-half-long class. I had never known such foot pain. I began to live by the clock, counting the minutes until another hour had passed and we were given our union-mandated five-minute break. I searched for ways to stand that might give my feet some degree of relief. I rocked back and forth from leg to leg, giving each one a chance to be pressure-free while the other took all my weight for a minute. The glory of sitting down – oh, it was pure nirvana. Even kneeling felt blissful. I would happily, joyously, gratefully spend five minutes on my knees if the choreography called for it. Anything, anything, to get off my feet.

“….I did have a few blisters, but even worse were the ‘zingers,’ the electric zapping sensations that shot through my toes and couldn’t be taped or padded. The inner sole (the shank) of a pointe shoe is slightly smaller than the length of the dancer’s foot, and the place where my heel overhung the shank burned so much I expected to see blood, but the skin wasn’t broken….

“…When the one holy hour each day that was my lunch break finally arrived, all I could do was lie on my back with my legs straight up in the air, feet overhead, and wish upon wish that I didn’t have to put my pointe shoes back on. I didn’t know how the day could be only halfway over, how I could conceivably do this for another three hours….

“…Delaying the inevitable moment of putting my pointe shoes back on was always a mistake, since the initial few minutes inside them was the worst. At then minutes before four o’clock, I re-taped my toes, vainly hoping that fresh athletic tape and corn pads would magically alleviate the pain. I gave my arches one final stretch and pulled each pointe shoe back on, almost stunned at how disgusting it felt. Awkwardly standing up, I could not conceive of dancing, or doing any ballet steps at all, but luckily, walking was harder than dancing.” [18]

Many have claimed for decades that pointwork is a practice as barbaric as the bygone Chinese practice of binding women’s feet: Larsen’s account gives potent support to that argument. (Fonteyn once remarked that, if people knew how painful ballet was, it would appeal only to people who enjoy bullfights. [19])

Yet Larsen somehow transcends that ordeal, which occurs only a third way into her book. Her step-by-step ascent to ballerinadom is not a staircase of pain or injury or resentment. And, though it abounds with personal detail, it’s both much less than the Gavin Larsen Story and much more.

Along its way, Being a Ballerina has obvious weaknesses. Why, having named two of her School of American Ballet teachers as Mr. Rapp and Madame Tumkovsky (“Tumey”), does Larsen coyly avoid naming two other instructors, whom instead she calls “the Curly-Haired Teacher” and “the Pastel Teacher”? (She goes out of her way to make them sound like Suki Schorer and Susan Pilarre, too.) She muddles her spelling of French ballet terminology: she writes “ronde de jambe en l’air” (p.14), when the first word should be “rond”; “grands battements” (p.18), which is correct, but then “grand jetés” (p.38), which isn’t; and so on. Chapter 47 - “A Conversation with My Feet”, beginning “Hello, feet. I haven’t seen you in a while…” - is an exercise in tweeness. In Chapter 54, “A Boyfriend and a Cat”, the way she keeps the cat but dumps the boyfriend is thoroughly awkward for those of us trying to work out who Larsen is.

Yet discard all that. Few if any books have ever taken us so acutely into multiple facets of the dancer’s art. Larsen’s quick, anecdotal chapters are more album than narrative: they give us acute glimpses of crucial or revealing career moments. In one shrewd and telling chapter (no 36), she marvellously analyses the challenges of dancing adagio:

“Among my colleagues, I was known to be a perfectionist, which is silly to say because every dancer is, in some way, obsessed. We all get crazy over something having to do with technique: maybe it’s speed, height, pure brute strength, ‘tricks’ (the flashy, bravura step that makes audiences go wild), or the subtleties of partnering. My personal craziness was a fixation on details and precision. I calculated the placement of each millimeter of my body and every nanosecond of my movements. Finger positioning and the exact curve of my neck, shoulders, and arms were my hallmarks. Turnout (which I was not born with) was not limited to my legs – I wanted to emanate outward rotation from the middle of my soul.

“An effect of my anatomical self-scrutiny was that I craved the satisfaction of perfect balance. And by perfect, I mean holding a position on my terms: every part of my body obeying my commands, arranged exactly just so. When everything is accurately lined up, you are completely at ease, there is no struggle, just the continual outward stretch of each muscle away from your center. It’s a stasis that keeps the energy moving and the shape alive. It’s a feeling like no other. You’re a body of water that appears still, though the current flows swiftly beneath its skin. And then, when you are ready, you decide to bring yourself out of that balanced position and on to the next. You don’t fall out of it because you’ve lost control, you take yourself out of it.

“We think of those balances as being most impressive when they’re held on pointe or demi-pointe, but performing an adagio, with its sequence of slow extensions and smooth transitions, is just as balance-challenging as a static pose, if not more so. Your center of balance keeps shifting. There isn’t time to look for it – you have to have it in hand while you’re moving and be balanced before you even arrive. Most dancers dislike adagio because of its slowness, but I loved it, for perfecting an adagio meant having utter control. The majesty of long, weighted, movement, seamless flow from one second to the next, leaves time for pure beauty. Purity of shape and movement. Pristine cleanliness. Glory, Bliss, Peace.

“Usually, in class, an adagio exercise is done at the barre and then again in center. At the barre, of course, the goal is less about balance and more about strength (holding a leg as high as possible with correct alignment, for as long as the music dictates). In center, that strength challenge quadruples. Your core muscles are what holds up your leg, with no assist from your hand on the barre. Through my obsessive explorations, I learned that perfect balance is achieved when the strength at the middle of one’s body is equal to the dynamic energy being stretched out to its extremities – the fingertips, toes, and the tops of the head. Push from the center, pull outward from the edges.

“Once my body figured that out, adagio was fun – not easy, but the kind of physical puzzle my detail-centric mind found satisfyingly hard. I could, in any given adagio exercise, usually perform some portion of it with the kind of ease I knew was ideal. A sixteen- or thirty-two-bar exercise, though, is a long time to be so pinpoint correct. But I never stopped trying.” [20]

This remarkable analysis of the inner feeling of dancing is something few dancers have ever managed effectively; Larsen bring it off at several other points of her memoir. In one chapter, she takes us through the sublimity of executing one particular performance of the Nutcracker Sugarplum pas de deux. She analyses successive details of working with a partner in choreography they know well.

“Arthur’s hand at my waist is warm, his grip firm and encouraging. And then, suddenly I’m aloft, unfolding my legs into a full split, arms overhead, reaching my feet and stretching my limbs for eternity, every cell driven by the power of the orchestra raging under us likes the waves of an ocean.

“Ever since I walked onstage at the start of the pas de deux, my thoughts have been a fast-moving, shifting stream of second-by-second calculations and adjustments. I hadn’t consciously told myself what steps came next; my body knew the choreography on its own. Sensations like the heat of the stage lights, a glimpse of someone in the wings, and the roughness of the fabric of Artur’s tunic against my skin registered distantly, well below the current.

“But suddenly, at the height of the lift and on that one magnificent note, everything was crystal clear: this is the apex of life. This is the happiest a person on earth can be. This is perfection.

“I may never be this happy again. And that’s okay.”

This is hyperbole - and yet it’s not. I’ve never seen Larsen dance the Sugarplum adagio, but I believe her account of this ballerina bliss, because I’ve known other dancers make me feel the same way. Yes: their rapture becomes ours.

Karsavina, Fonteyn, Seymour, Makarova, Seymour, Farrell, Ashley – greater celebrities than Larsen by far, and historically more important artists – tell their stories of their lives much better than she, and explain who they are far better. Yet they do not take us into this core level of a ballerina’s experience so profoundly. It’s an important addition to the dance bookshelf – and an important, sensitive, intelligent case study in ballet as psychological odyssey.

@Alastair Macaulay, 2021

[1] Marie Taglioni, Souvenirs - Le Manuscrit inédit de la grande danseuse romantique, ed. Bruno Ligore).

[2] Lydia Kyasht, Romantic Recollections, edited by Erica Beale, 1929, p.122.

[3] Gavin Larsen, Being a Ballerina (University of Florida Press), p.113.

[4] Margot Fonteyn, Autobiography, W.H.Allen, 1975., p.94.

[5] Fonteyn, op. cit, p. 127.

[6] Fonteyn, op. cit, p. 138.

[7] Fonteyn, op. cit, p. 142.

[8] Pazcoguin, Swan Dive: The Making of a Rogue Ballerina, p. 41.

[9] Pazcoguin, p.234.,

[10] Pazcoguin, p.3.

[11] Conversation on Dance no 255, Georgina Pazcoguin On Her New Book “Swan Dive”.

[12] Pazcoguin, p. 136.

[13] Pazcoguin, p. 155.

[14] Pazcoguin, p. 243.

[15] Text shared by New York City Ballet press office, September 28, 2018.

[16] Larsen, p.6.

[17] Larsen, p. 12.

[18] Larsen, pp. 71-73.

[19] Fonteyn, quoted in Keith Money, The Art of Margot Fonteyn, 1965. Dance Books, 1975 edition.

[20] Larsen, pp.137-138.

3: Georgina Pazcoguin in the world premiere of Alexei Ratmansky’s Voices (New York City Ballet, 2020). Photograph: Erin Baiano.

5: Georgina Pazcoguin and Jared Longhitano, October 2017, Lincoln Center

6: Jared Longhitano’s Instagram caption to photographs 4 and 5.

.

8: Jared Longhitano‘s Instagram caption to photo 7.

9: Jared Longhitano.

10: Jared Longhitano’s Instagram caption to photo 9.

.