Michael Cole: Black History Month in Dance, 2021

Black History Month in Dance 117, 118, 119. Michael Cole danced for over nine years (1989-1997) in the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, the third of four highly individual African American male dancers who distinguished the company between 1964 and 2011. In the year of his joining, Cunningham made the classic “August Pace” (1989) for what was recognised as a vintage company, with Cole jumping, jumping, and jumping again during a featured duet with Larissa McGoldrick: Cunningham tailored individual moments to make Cole’s role especially vivid and personal.

Cole was there during a period of crucial and complex transition. When he arrived, in 1989, Cunningham himself was still dancing in every single Cunningham performance (in November 1989, that factor ceased to be constant). Cole was there while, in 1991-1997, Cunningham began to compose dances with the assistance of a computer; there when, in 1982, John Cage died and a long period of complex and painful administrative fallout caused havoc and distress across the Cunningham enterprise; there for both the magnum opus “Enter” (1992, world premiere at the Paris Opéra) and the next magnum opus “Ocean” (1994, world premiere at the Brussels Cirque Royal).

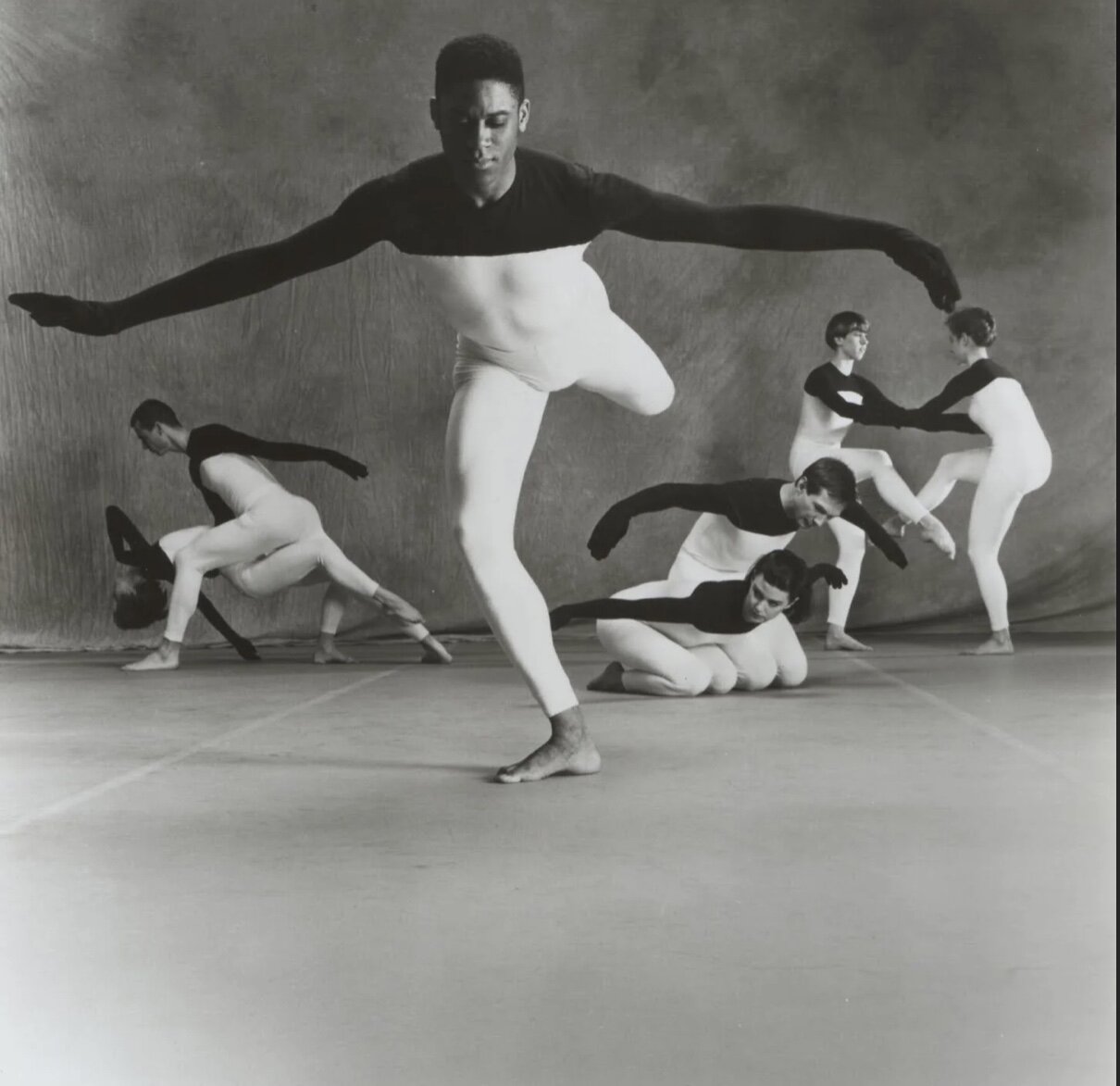

Over the decades, certain feats of balance/imbalance on one leg in the Cunningham repertory become legendary: I immediately think of Helen Barrow’s prolonged seconde in “Quartet” (1982), Karen Redford’s Shiva-like attitude front in “Pictures” (1984), and Silas Riener’s hopping, bending solo in “Split Sides” (2003) - but the whole Cunningham repertory is dotted with various examples of balance both as stasis and as changing negotiation. Cole’s balance in Cunningham’s “Beachbirds” (1991) and “Beachbirds on Camera” (1993), leaning forward in attitude back with slowly moving arms that suggested both a wading bird’s long wait and a flying bird’s seeming immobility on a stream of air, was one of those legends. (See photo 117, by Michael O’Neill; and photo 118.) Over seasons and years, Cunningham coaxed Cole into sustaining that balance for whole minutes. Other things were happening elsewhere in the choreography; it was very possible to focus on other matters - until Cole’s breathtaking fixity began to dawn on you. “Beachbirds” was one of Cunningham’s classic nature studies, more literally imitative of bird behaviour than any other Cunningham work and yet with just enough complexity and mystery to remain elusive: Cole was part of its heart.

In 2019, he and twelve other 1989 Cunningham dancers coached their original roles in “August Pace” at New York City Center. I was able to watch rehearsals: the delight shown by the alumni in working with today’s young dancers was palpable, none more so than Cole’s for Mac Twining (see photo 119), the wunderkind who was inheriting his role, jumping, jumping, and jumping like the young Cole.

Since leaving the Cunningham company, Cole has gone on to enjoy success and eminence as a motion graphics designer - yet, in some 2019 conversations with me and others, he made clear that he regards his Cunningham years as the most important time of his life. He has just a single regret about them: that during those years he never danced the Cunningham repertory with another black performer. This was said without acrimony: at that time, few important troupes at that time had more than one African American dancers. But Cole had danced once with another black dancer in another company; that had left a good feeling he would have liked among the many other good feelings he took from his Cunningham experience.

Saturday 20 February

117. Michael Cole in Merce Cunningham’s “Beachbirds” (1991). Photo: Michael O’Neill.

118: Michael Cole in Merce Cunningham’s “Beachbirds for Camera” (1993)

119: Mac Twining, left; Michael Cole, right, after 92nd St Y performance of Merce Cunningham’s “August Pace” (1989) in November 2019.