Mark Lancaster (1938-2021), superlative designer for Merce Cunningham dance theatre, R.I.P.

The British-American artist Mark Lancaster (1938-2021) died on Sunday 30 April, aged eighty-two. He was responsible for many of the greatest and most poetic stage designs of the twentieth century, chiefly as designer for Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1975-1984 (with some return visits up to 1993).

British born, he began to visit New York from 1963 onward. In 1968, back in the U.K., he was invited to be the first-ever artist in residence to King’s College, Cambridge; he made friends there with E.M. Forster, George “Dadie” Rylands, and others. In 1972, he was one of six British artists commissioned by Richard Buckle to paint new work in response to Titian’s “The Death of Actaeon”, when there was a nationwide campaign to save that painting for the U.K.. A little later, he worked in New York as assistant and secretary to Jasper Johns, through whom he entered the orbit of Merce Cunningham. As he began to help with Cunningham designs, he at once discovered his own art’s best niche. Whereas Johns usually preferred to attend Cunningham performances to designing for them, Lancaster was instinctively right for theatre work - it released his lively, ebullient nature and his keen sense of play. He also knew a vast amount about lighting as if by keen instinct: effects of contrast, silhouette, shading, and more.

Lancaster, above all, brought to the dance stage a marvellous sense of colour, so that several of the Cunningham dances he designed (“Squaregame”, 1976; “Fractions”, 1977; “Doubles”, 1985; “Five Stone Wind”, 1988) seemed to have palettes taken from Cézanne paintings. The former Cunningham dancer Catherine Kerr recalls some of Lancaster’s earliest designs for Cunningham, those for “Rebus” (1975): “the women wore pink tights, and white leotards with arms colored various glorious hues. Merce had talked about watching flocks of birds swirl through the air while making this dance. I always thought Mark caught that with the colors.” Most Lancaster designs felt at once so definitive that it’s a shock to be reminded that the original 1980 Cunningham production of “Fielding Sixes”, though I reviewed its world premiere, was designed by Monika Fulleman: the visual look of that dance was immediately superseded in my mind by Lancaster’s 1983 designs for the Ballet Rambert production (a staging I saw often).

Lancaster also knew how to create drama by colour contrasts: “Duets” (1980) and “Trails” (1983) placed one strong colour strikingly against another. For “CWRDSPCR” (1993), he made Harlequin effects of bright colours juxtaposed in blocs on the same body. Its composer, John King, writes how “those costumes added such energy to the very energetic dance!”

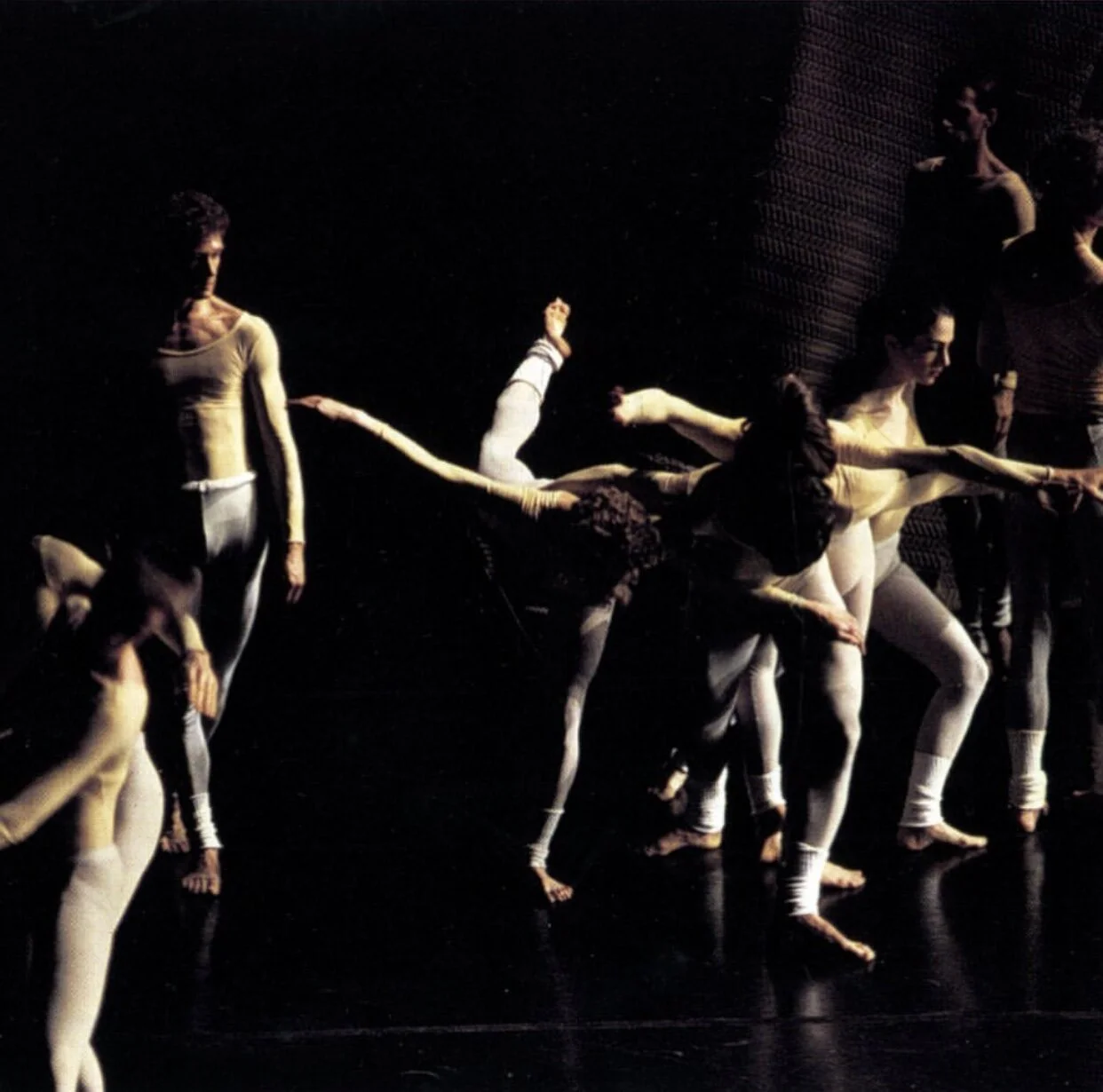

Perhaps Lancaster’s greatest and most loved design had the most limited colour-scheme: in Cunningham’s “Pictures” (1984 - the most performed Cunningham work to this day), the dances wore only dark blue and black, the backdrop was pearly white, and the miraculously sudden changes of lighting cast the dancers’ many horizontal tableaux into one breathtaking silhouette after another. In “Sounddance” (1975), a knockout work often revived since Cunningham’s death, the palette was equally restricted, with the sand-coloured folding curtains of the decor matching the dancers’ tops, while their tights were off-white. In “Quartet” (1982), all colours were sombre; here was one of Cunningham’s most bleakly powerful dramas.

When Lancaster came to the Cunningham company, Charles Atlas was also its stage manager and was beginning work as its filmmaker-in-residence, as well as designing and lighting a number of works. The Atlas-Lancaster combination made for one of the peak visual periods of the Cunningham enterprise. Atlas left in 1983, Lancaster in 1984, but both had deep connections of temperament with Cunningham’s work and returned at later dates.

In 1999, after Lancaster and I had been among the speakers on a Cunningham panel at Lincoln Center, he suddenly said to me “I should never have left the company”. Although he painted, he had found with Cunningham dance theatre the poetry and wit that suited him best. He loved returning to work with Cunningham: and he loved it again after Cunningham’s death, when in 2010 he returned to Cunningham’s hour-long Roaratorio” (1983), making subtle and imaginative revisions.

Cunningham would give his artists a free hand but also often a single clue. For “Sounddance” (1975), he simply told Lancaster that he wanted a set that would make the dancers enter at the middle of the stage. Lancaster then devised a horizontal partition with a flap like a draped doorway: it was ideal for the dance Cunningham was devising, in which Cunningham himself entered first and left last: others followed (but left earlier), with the choreography giving the stage action an often desperate quality, as if this stage space were affected by unseen violent forces beyond, as with a black hole.

In this century, Lancaster lived in Miami, Florida, with his partner and fellow artist, David Bolger. On my 2007-2010 visit there, he would take me to parts of the city I might otherwise not see; I would take him to performances by Miami City Ballet; we would dine afterwards. (He loved ballet.) He was an enthusiast, humorous and passionate about art, dance, and criticism, with a great capacity for high spirits and a good memory. Even so, I wish there had been more such times; and I shall always miss the rare and exquisite textures he conjured from colour in decor, costumes, and light onstage. I do not throw the word “great” around lightly: all who saw the original productions of “Sounddance”, “Duets”, “Pictures”, “Roaratorio”, “Doubles”, “Five Stone Wind” will remember the impact they made. Though those works can be revived, few know the secrets of lighting them so that a lemon or blue or red suddenly sing out and catch your heart.

Monday 3 May

1: Mark Lancaster in the 1960s. Photo @ Chris Morphet.

2: “Sounddance”, designed by Lancaster, choreographed by Merce Cunningham

3: “Sounddance” (more)

4: “Sounddance” (1975), choreographed by Merce Cunningham, designed by Mark Lancaster

5: Costume design by Mark Lancaster for Merce Cunningham’s “Duets” (1980).

6: Costume design by Mark Lancaster for Merce Cunningham‘s “Duets” (1980)

7: Louise Burns and Robert Kovich in the original production of “Duets” (1980), choreographed by Merce Cunningham, with designs by Mark Lancaster

8: Chris Komar and Susan Emery in the original production of “Duets” (1980), choreographed by Merce Cunningham, designed by Mark Lancaster.

9: Joseph Lennon and Lise Friedman in the original production of Merce Cunningham’s “Duets” (1980), designed by Mark Lancaster.

10: Alan Good and Karole Armitage in the original production of Merce Cunningham’s “Duets” (1980), with designs by Mark Lancaster.

11: Merce Cunningham and Catherine Kerr in the original production of Cunningham’s “Duets” (1980): costumes by Mark Lancaster.

12: Merce Cunningham’s “Pictures” (1982): lighting and costumes by Mark Lancaster.

13: Helen Barrow, Joseph Lennon, and Alan Good in Merce Cunningham’s “Coast Zone” (1983): costumes by Mark Lancaster.

14: Merce Cunningham‘s “CRWDSPCR” (1993), designed by Mark Lancaster.

15: Ray Johnson, “Mark”, 1969, detail. (Ray Johnson to Ann Wilson from Bellevue 3 September 1963: “Mark Lancaster came to see me wearing an elegant English blue suit made by the Beatles’ tailor and Sari Dienes floated in and talked and talked and talked.”)

See the May 5 Instagram post by the Johnson scholar Ellen Levy.