Julia Farron (1922-2019), and her place in ballet history

Julia Farron

With particular thanks to Gail Monahan, Farron’s student and friend

Versatility, attack, imagination, authority: these virtues stamped performances by the British dance artist Julia Farron from the 1930s to the 1970s. A dancer with today’s Royal Ballet, which she had joined when it was the Vic-Wells Ballet, she created roles for many choreographers, several of which now remain today in the repertories of American, British, and other companies.

And though she appeared in ballets to music by Chopin, Delibes, and Tchaikovsky, she also performed to a wide range of new music. The 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s were an era when many scores were commissioned for British dance: Farron danced in world premieres of at least 17 scores by 12 composers, often in solo or lead roles: these composers were Denis ApIvor (A Mirror for Witches”), Malcolm Arnold (Homage to the Queen), Lord Berners (A Wedding Bouquet, Cupid and Psyche, Les Sirènes), Arthur Bliss (Miracle in the Gorbalsand Adam Zero)[1], Benjamin Britten ( The Prince of the Pagodas), Roberto Gerhard (Don Quixote), Hans Werner Henze (Ondine), Constant Lambert (Horoscope and Tiresias), Mikis Theodorakis (Antigone), Michael Tippett (she danced a solo in the premiere of his opera A Midsummer Marriage), William Walton (The Quest), and Ian Whyte (Donald of the Burthens).

There are many other layers of dance history that the remarkable Farron embodied. Between 1937 and 1965, she created roles for a number of eminent choreographers – Frederick Ashton(she was Pépé the Dog in A Wedding Bouquet, 1951; Psyche in Cupid and Psyche, 1939; a leading soloist in Dante Sonata, 1940; Faith in The Quest, 1943; one of the Smart Set in Les Sirènes, 1946; one of the three Nymphs of Pan in Daphnis and Chloë, 1951; the Neapolitan Dance in Swan Lake, 1952; Diana in Sylvia; Homage to the Queen, 1954; Sibylla in Rinaldo and Armida, 1955; Berta in his three-act Ondine), John Cranko (the solo in A Midsummer Marriage; she was Jocasta in his Antigone and Belle Épine in his three-act The Prince of the Pagodas), Robert Helpmann (in the original 1944 Miracle in the Gorbals, she was one of the residents; in Adam Zero, 1946, she was the Wardrobe Mistress, “His Fate”), Andrée Howard (she was Hannah in A Mirror for Witches 1952), Kenneth MacMillan (Lady Capulet in his three-act “Romeo and Juliet,” 1965), Léonide Massine (she was the Mother in his 1951 Donald of the Burthens), and Ninette de Valois (the Lady Belerma in Don Quixote, 1950). She also became known between 1962 and 1989 as an inspiring teacher at both the Royal Ballet School and Royal Academy of Dance. She died on July 3, 2019.

Farron was born in London in 1922 as Joyce Margaret Farron-Smith; her parents were Hugh Farron-Smith, a civil servant, and his wife Amy Ellis, a teacher. (A younger brother, David, predeceased her.) She studied all kinds of dance in childhood; and she was impressed by a Camargo Society performance of Ninette de Valois’s Job (1930) to which her mother took her, with Anton Dolin as Satan. (“It wasn’t ballet as I expected it to be.”[2]) But she always remembered that when she was between ten and twelve an actor told her “You should think about being an actress.” “But I want to be a dancer,” said the young Farron. “I know,” said the actor, “But you should think about it.”[3] In 1934 or earlier, she became one of the first two scholarship students to the Vic-Wells Ballet School; her school had entered her.[4] It was the Vic-Wells Ballet’s artistic director, de Valois, who chose the name “Julia Farron.” As a student, she danced Little Bo-Beep in de Valois’s “Nursery Suite” (choreographed to a recent Elgar score) and then – December 1934 – as Clara in Nicholas Sergueyev’s revised version of Casse-Noisette (The Nutcracker), which he had staged earlier the year. Casse-Noisette brought her first chance to dance with an orchestra (“a great thrill”).[5]

Joining the Vic-Wells Ballet[6] in 1936 on her fourteenth birthday, Farron was immediately cast by de Valois as one of the four cygnets in the first lakeside scene of Lac des cygnes. These cygnets dance with hands linked in a single horizontal line throughout their famous dance; the smallest dancer in the company, Farron was much shorter than the others. De Valois, trying to make the disparity of height less troubling, switched Farron around from the centre to the side of the line. Then de Valois said “That’s worse – but you’ll just have to do it.”[7]

Farron was still the company’s smallest and youngest dancer when, in April 1937, she created the role of Pépé the Dog in Ashton’s A Wedding Bouquet. This was danced to a Lord Berners choral score[8] employing words by Gertrude Stein – who, while writing in Everybody’s Autobiography (1937) of her belief that Ashton was a genius, took delight in the little girl cast as the dog.

Ashton, however, told Farron, “Now you must grow.”[9] She did, eventually teaching five foot five inches[10], and creating roles for him over the next 21 years. (The role of Pépé soon passed to smaller dancers.) Good-humoured, frank, intelligent, imaginative, and hard-working, Farron happily absorbed everything she could from de Valois, Ashton, the music director Constant Lambert, and the star male dancer Robert Helpmann. While she acquired a strong technique, with fast footwork and a vivid upper body, she also became a noteworthy dance actor.

In 1936, Margot Fonteyn’s mother had taken her daughter, Pamela May, and June Brae to Paris to study with the three foremost Russian émigrée ballerinas, Lubov Egorova, Mathilde Kschessinskaya, and Olga Preobrazhenskaya. The three British ballerinas made the journey each summer until (and including) 1939. They would return enriched in many ways. Farron later remembered that de Valois, while teaching company class at Sadler’s Wells, sometimes was called away by a ‘phone call; on such occasions, Fonteyn and May would fill in by teaching steps they had learned in Paris that were absent from de Valois’s lexicon, such as temps liés.[11] In 1937, however, the whole company went to Paris for the world premiere of de Valois’s Checkmate at the time of the Paris International Exhibition. (There was almost no advance publicity, so the company danced to half-empty houses. Word got around during the week, however. Among those who attended was the great maestro Arturo Toscanini, who named Checkmate as his favourite ballet.)[12] De Valois sent her dancers off to study with the three émigrée ballerinas and to take notes; Farron duly went to Egorova’s class, but, as she remembered sixty years later when she rediscovered those notes, found those classes strangely thin.[13]

In later years, Farron loved to reflect on what she and her contemporaries learnt then. De Valois’s (“Madam’s”) ballet teaching was quite unlike the way it was after the Second World War: “When I think back to Madam’s teaching before 1945, it was all below the hip – really all below the knee.” From Ashton (“Fred”), who had many high-society connections, they learnt about personal style and elegance; in the studio, “Everything we ever knew about épaulement we learned from Fred.”[14] More than that, the dancers derived their sense of social behaviour from him; worshipping him, they assumed that anything he said about manners and presentation must be right.[15] Helpmann (“Bobby”) was already becoming a distinguished stage actor as well as dancer: “Half of what I ever knew onstage I learnt from Bobby.” (Helpmann’s most peculiar rule was that you should never look into the eyes of a fellow performer but a central point low in his or her forehead. Farron followed this rule with him but looked others straight in the eye.)[16]

De Valois, in a pioneering stroke that did much to change international ballet history, had decided that the nineteenth-century ballet classics should be the foundation stones of her company’s repertory: today a standard decision, then an unprecedented establishment of a canon.[17] Between 1932 and 1939, Coppélia,Giselle, Casse-Noisette (The Nutcracker), Le Lac des cygnes (Swan Lake), and The Sleeping Princess (The Sleeping Beauty) were staged for the Vic-Wells by Nicholas Sergueyev, who had been régisseur of the Russian Imperial Ballet and had left Russia with most of the notations and other records of the traditional repertory of the Mariinsky Ballet. Sergueyev also taught class: although Margot Fonteyn (three years Farron’s senior) and Pamela May (five years) were fond of him and valued what they learnt, Farron remembered how he was an old-fashioned teacher who not only carried a stick but used it on the legs of offending dancers.[18]

When he staged The Sleeping Princess in 1939, Sergueyev cast Farron in four roles: the fifth fairy (the “finger” variation – so called because of its repeated finger-pointing gestures) in the Prologue, one of Aurora’s friends in Act One, one of the nymphs in the Act Two Vision, and the Sapphire Fairy in the Act Three pas de quatre of Jewels.[19] Although the designs by Nadia Benois were a disappointment to the dancers, de Valois had chosen unobtrusive designs because she felt the 1921 Diaghilev production of The Sleeping Princess had been blighted by visual excess. (There were muddles. Although the third Prologue fairy was designated by Petipa and Tchaikovsky as “Miettes qui tombent”, somehow it was the fifth fairy – Farron – who became named “the Breadcrumb Fairy.” Her headdress featured two upright ears that resembled slices of brown toast; sixty years later, Farron loved to recall how she was known as “the Hovis Fairy”.[20]) De Valois’s policy was justified: the 1939 production was an immediate success; and it was in this that Farron, still aged sixteen, first danced at Covent Garden, in a gala in honour of the visiting President of France.[21] It seems revealing that Ashton, writing at this time of Petipa’s choreography in Dancing Times, singled out the “finger variation” as his favourite from the Prologue.[22]

Lambert’s conducting, she recalled, “held it all together”[23] and was “wonderful.” He made recordings of parts of the Sleeping Beautymusic at this time on 78s. Heard today on YouTube or CD[24], their tempi seem impossibly fast, but evidence suggests he did indeed take those speeds in the theatre. When she first danced the “finger variation,” she found its opening “run-on” difficult at his speed. When she asked him if he could slow it down, however, he replied “I have to keep sixteen-seventeen members of the orchestra together - and there’s only one of you. So speed up!” She never mentioned any change of tempo to him after that. [25]

Farron’s teenage promise impressed many; the critic Arnold Haskell (who later gave the advice “Never predict” to younger critics) predicted great things for her in his book Ballet if she fulfilled only a quarter of her potential. In April 1939, when she was only sixteen, Ashton cast her as one of the two title characters in Cupid and Psyche: Cupid was Frank Staff. Lord Berners wrote the commissioned score; Francis Rose created the designs. (In this version, Mount Olympus was populated by bawdy and drunken deities.)[26] Farron delighted in the process; she long recalled the spontaneity of Ashton’s creative method. One day, making an ensemble dance, he spotted the way children in a playground opposite Sadler’s Wells were making an irregular loop as they formed a moving chain: at once, he incorporated that into his ballet.[27] Farron also long remembered the solo he made for her, which was reconstructed in 1970 (danced by Marilyn Trounson) for the retrospective tribute to him when he retired as director of the Royal Ballet.[28] Despite all this, however, the opening night of Cupid and Psyche proved a fiasco, with various scenic and performance disasters. (“The costumes were incomplete, the conductor was drunk, and Julia Farron herself was knocked over by a flying stunt that went wrong. The ballet was booed off the Sadler’s Wells stage.”[29] ) Staff quickly returned to Ballet Rambert. Farron remained a favourite performer of Ashton’s, but seldom thereafter played the protagonist of any ballet. She played many principal and solo roles from the 1930s, and yet well into the 1950s she also often remained in corps or coryphée roles.

Farron retained lifelong friends from this era. Sixty years later, she would entertain to lunch such former dancers as Margaret Dale, Pauline Garnett, and June Vincent: her Vic-Wells contemporaries. All of them shared the same impressions and memories of de Valois, Ashton, Helpmann, Lambert, and touring.[30]She and Dale recalled how they were sometimes sent at short notice to such cities as Manchester to dance in a local production of Verdi’s opera Aida: in those days, the Aida choreography for the Sadler’s Wells production worked perfectly well in other stagings of the same opera.[31]

Farron and her friends grew up as they began to understand the dynamics between the senior members of their company. Talking of Ashton’s Horoscope (1938) in 1997, Dale and Farron recalled that it expressed the intense loves that Constant Lambert and Ashton both felt at that time: Lambert for Fonteyn, Ashton for Somes. (“You must understand,” said Dale, Horoscopewas about Constant and Fred being deeply in love.”[32]) The Fonteyn-Lambert affair, begun in 1936 when Lambert was still married, was sexually passionate: the younger dancers found it hard to understand how Fonteyn in her teens could be attracted to Lambert, who, despite his charm and intellectual brilliance, was already a serious drinker; his looks had begun to go to seed. But Farron, reflecting in old age, recalled that Fonteyn’s mother, Mrs Hookham (who in 1937 acquired the permanent nickname “Black Queen” after a character in de Valois’s Checkmate) was very controlling. For Fonteyn, to take up with Lambert was one way to escape her mother: “though Black Queen might have objected, she wasn’t going to complain about Constant.”[33] The Ashton-Somes relationship was more complicated, since Somes was heterosexual: Somes, a strikingly handsome man, was the greatest love of Ashton’s life, and Somes became Ashton’s leading male dancer, staunchest admirer, and most loyal devotee for decades to come.[34]

Farron and most of her contemporaries stayed with the Vic-Wells company as it performed its way through the Second World War. Ashton announced that he was reading the Bible and that, when he had finished, the War would be over.[35] In the event, he had read the Bible and several other books of spiritual direction before the War ended; the anguish of that time entered into some of his new ballets, notably the barefoot Dante Sonata (1940), in which Fonteyn, May, and she danced the leading female Children of Light roles. (The ballet, after fifty years of neglect, was revived in 2000. Farron assisted in its revival by her old colleague Jean Bedells.) In spring 1940, the Vic-Wells made a propaganda tour to France, Belgium, and the Netherlands, but, soon after performing in The Hague, German soldiers marched into the town. The dancers, now in extreme danger, were trapped in their hotel. “After three days, they were smuggled out of the country in the stinking hold of a cargo ship that was repeatedly bombed on the North Sea by German aircraft.”[36]

At this point, the company was split into two groups; every role had to be double-cast. In The Rake’s Progress (1935), Farron had to learn the role of the Betrayed Girl, the ballet’s heroine, in a hurry. “Mary Honer taught me the part. We had no music and Mary simply hummed the music and taught me the steps.” Farron gave her first performance in a provincial theatre; de Valois attended. “Afterwards she came to my dressing room and said ‘What do you think you were doing?’ This was wrong and that was wrong…. I burst into tears and she said, ‘What’s the matter, child?’ I said, ‘We didn’t have a rehearsal,’ and she replied, ‘Rubbish!’”[37] Thus began Farron’s long association with a role she performed for many years. Like many devotees of British ballet, she believed The Rake’s Progress was a masterpiece.[38] She insisted that it was not a ballerina role but a character role; it should not be performed with particularly classical emphasis.[39]

There followed the London Blitz, when the Vic-Wells and other companies danced through the bombs. Signs would warn the audience to go to the air-raid shelters; the dancers would continue performing; audience stayed riveted to their seats. “You try dancing the Prelude in Les Sylphides when you can hear the double-doors at the back of the circle swing to and fro because of the vibrations from the bombs!,” May loved to say almost sixty years later.[40] Perhaps the most remarkable occasion was a Fonteyn-Helpmann performance of the complete Lac des cygnes. The Petipa choreography for Odile’s adagio with Siegfried used to end with Siegfried kneeling and Odile, holding his knee with both hands, taking an arabesque penchée on point; on this occasion, the theatre had been shaking more than usual during the air-raid but, as things grew quiet at the end of the adagio, Fonteyn in that penchée turned her head to the audience with a wide smile as if to say “We have survived.”[41] Farron and Dale would remember how Fonteyn gave individual Christmas presents to each dancer in the company, revealing to their surprise that she had a sure understanding of what each one was most interested in.[42]

It was around the beginning of the War that Farron had a romance with Somes (“my first love”). Other dancers, Farron later thought, felt she was a “little fool”; but Somes was “lovely” to her.[43] For a while, things were intense enough that, when the company went on tour, Mrs. Farron-Smith went out as chaperone. [44]Somes in due course was enlisted in the army, Ashton in the air force; de Valois refused to petition for her male dancers to be exempted from military service.

Robert Helpmann, however, was exempt as an Australian citizen. A star of magnitude, he and Fonteyn kept going throughout the War: for many people, his theatricality made him more compelling at this stage than Fonteyn, who always expressed her gratitude for the chance gradually to learn how to hold her own beside him. Not only that, he used the absence of Ashton as his chance to start choreographing: his one-act Hamlet psychodrama (1942) made an immense impression despite its lack of dance content. (Farron was later to dance the Queen of Denmark in this ballet between 1947 and 1958.[45])

This notwithstanding, Helpmann also kept the company entertained. Farron loved to recall how, having arranged to lie motionless and face down in one passage of Hamlet (a swoon for the protagonist), he then secretly rigged up a microphone to that part of the stage. Without the audience seeing him, he would then speak into the microphone and take the dancers and staff backstage by surprise. On the first occasion, he gave instructions to his dresser, who was so startled to hear his voice when she knew he was onstage that, in full view of the dancers backstage, she dropped everything she was carrying. On later occasions, he would idly give instructions for cookery (“For the perfect soufflé….”) <41>

Ashton came back to the company when his work permitted. Farron loved to recall how he once turned up to greet his colleagues before a “Giselle” performance but was at once required to perform that evening as Hilarion, “a role he hated,” the gamekeeper traditionally given a red beard and shown as physically unattractive. (He had played it in 1932 and 1934 to the Giselles of Olga Spessivtseva and Alicia Markova and had continued with the Giselle of Margot Fonteyn.) When it came to the scene when Hilarion mimed to Albrecht “Is this your sword?,” Ashton slapped his hand furiously on the sword but addressed Lambert, conducting, rather than Albrecht (Helpmann). “Of course Fred couldn’t be unmusical,” Farron recalled, “So he was exactly on time as he looked at Constant and mimed ‘Is This Your Sword?” Lambert, looking up from the pit, had tears of laughter pouring down his face. In 1942, Farron was one of the original cast in Ashton’s The Wanderer; she created the role of Faith in his The Quest.[46]

Some dancers left the company during the War; others joined. A new arrival in 1942 was an old friend of Farron’s, Pauline Clayden. Farron and Clayden had known each other as young girls before Farron joined the Vic-Wells company; they remained good friends all their lives. Ashton was fond of them both: they were vivid dancers with intense sense of characterization.

These wartime years were when the young Moira Shearer and Beryl Grey first joined the company. Farron shared a group dressing room with them both. Shearer, she later recalled, had a habit of claiming she was too unwell to dance the final performance of the week, which usually meant Farron had to replace her. Farron grew fed up with this pattern, so one Saturday evening (“I was booked to go out to see a play with a young man”) she took the evening off regardless of Shearer’s health claims. On this occasion, Shearer was genuinely too unwell to dance; Farron remembered de Valois’s subsequent fury.[47]

It quickly became apparent that Grey was going places: she danced her first Giselle in her fifteenth birthday. In later years, Grey sometimes adopted affected pronunciations, speaking the name “Moira” on her seventieth birthday as if it were French (“mwara”). When Farron was asked if Grey had always been affected that way, she replied, “When we knew she was getting big roles, she once paused as she left our dressing room to announce ‘I must just fetch a needle and cot-ton.”[48]

London theatre audiences might be devoted (the Vic-Wells company’s main London home in those years was the New Theatre, today’s Noël Coward) but audiences composed of the troops were less responsive, especially to the tenderly poetic plotlessness of Les Sylphides. Sometimes there were jeers. In one ballet, however, there was a sudden outburst of enthusiastic applause as Farron’s shoulder-strap broke: her partner, Leslie Edwards, covered her naked breasts with his hat.[49]

One number that Farron and Pamela May performed many dozens of times during the War was the Swan Lake pas de trois, sometimes out of context, usually in the ballet’s ballroom act. (Only after the War was it moved to its correct place in the opening scene.) The coda has a brisk sequence when they alternated in supported pirouettes. The two women loved to recall in the 1990s how once, just for a lark, they startled their male colleague by swapping roles: suddenly he found himself supporting May when he was expecting Farron, then Farron when he was expecting May.[50]

The highlight of her career, Farron later said, came when the Sadler’s Wells Ballet (as it was now known) moved to the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in 1946: a haven after the war’s vicissitudes.[51] Two of her first roles there were diametrically opposed: she was the Queen in the production of The Sleeping Beauty with which the Royal Opera House reopened, and then she was the Prostitute in Helpmann’s Miracle in the Gorbals (a role created in 1944 by Celia Franca, who had now left the company). Farron had gained a few pounds, so de Valois cast her as the Queen; Dale danced the finger variation. They were both aware that they were underpaid after dancing loyally throughout the War: they went together to plead for a pay rise from de Valois, but were so afraid of taking this unprecedented step that they would take turns to burst into tears, whereupon the other one would plead their case to de Valois. De Valois refused their request at first. As it happened, however, Farron and Dale were both singled out by reviews for their performances in the opening-night Sleeping Beauty – whereupon de Valois raised their pay after all.[52] In Miracle in the Gorbals, Farron was the Prostitute who seduced a minister and gloried in her power; but when the Stranger was sent to her room on a mercy errand, she emerged – a moment famous in Farron’s performance - with a new lyricism as if transformed by a vision.[53]

It had been Ashton rather than de Valois who had propelled the move to Covent Garden[54]. Now it was also Ashton who now moved further toward pure-dance ballets and into making dance the principal subject of almost all his work. De Valois was consistently a reactionary on choreographic matters; her correspondence with Joy Newton reveals that she was not happy with this development in his work.[55] It can therefore have been no accident that de Valois, between 1947 and 1951, repeatedly invited Léonide Massine to stage old classics of his for the company as well as to choreograph new ballets. To De Valois, Massine’s kind of characterful storytelling was what she most admired; as late as 1980, she referred to his as “the choreographer of the century.”[56]

Massine gave Farron several opportunities. She was a Jota dancers in the 1947 Sadler’s Wells Ballet premiere of Le Tricorne (1919); she and Harold Turner danced the Tarantella in the Sadler’s Wells production of La Boutique fantasque, a role (created in 1919 by Lydia Sokolova) she danced until 1955.[57] Later in 1947, she succeeded Fonteyn in the bubbly but featherheaded title role of Massine’s Mam’zelle Angot, only five days after Fonteyn had danced the premiere: it suited Farron much better, so that she continued to dance it up to 1951.[58] In 1951, she was the Mother in his new ballet, set in Scotland, Donald of the Burthens. [59]<54>

In 1948, Farron married the dancer Alfred Rodrigues (often known as “Rod”), a South African dancer born the same year as she who had joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1947. (Not long before their marriage, they had become entangled by their costumes in a 1948 performance of de Valois’s “Checkmate”: Farron was the Red Queen, Rodrigues a Black Castle. De Valois, for neither the first nor the last time, was furious.)[60] They both excelled in mime roles, sometimes playing the King and Queen in the same Sleeping Beauty performance. (In 1951, they played opposite each other as Princess Mother and von Rothbart in Le Lac des cygnes.)[61] In autumn 1949, while the Sadler’s Wells Ballet was making its epoch-making debut season at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, she gave birth to their son Christopher Rodrigues (Chairman of the Port of London Authority since January 2016, Chairman of the Royal Ballet School since January 2020 and Chairman of the Maritime & Coastguard Agency since April 2021; he was chair of the British Council in 2016-2019). When Ashton in a rehearsal told Rodrigues “Bend more” - his favorite correction - Helpmann exclaimed “He can’t bend any more, Fred, he’s just had a baby!” [62] Farron’s mother was invaluable in looking after the baby; Farron resumed her career.[63]

In the 1950s, Rodrigues became a choreographer working in several countries. He was always proud to have been the only man who choreographed for the two foremost opera-house divas of the day, Margot Fonteyn (in Île des Sirènes, danced by a touring group affectionately known as “Fonteyn’s Follies”) and Maria Callas (for whom he concocted a tarantella in Franco Zeffirelli’s production of Rossini’s Il Turco in Italia) at La Scala). He particularly loved to recall Callas’s singular way of selecting her dance vocabulary. Receiving him sitting down, she told him to show her the steps he might consider for her tarantella. She then accepted some steps and vetoed others: after which she told him to compose the dance from those she had approved. At stage rehearsals, however, she kept refusing to perform the tarantella, thought she assured him she was step-perfect. On the first night, she danced it superbly: Rodrigues described how she converted her one flaw – overbalancing in one swirl of the upper body while kneeling - into theatrical brilliance.[64] Farron in turn recalled observing Callas in a stage rehearsal of La Traviata at Covent Garden in 1958. “We had all done what we were told without creating a fuss. I had never seen anyone behave as she did, absolutely demanding changes be made. Not until Nureyev did I ever see anyone behave like that at Covent Garden – though he was worse. And really she was right: the production was not very good, and she was working to raise it to her standards.”[65] Rodrigues kept returning to the British ballet world, later teaching at the Royal Ballet School. He also later worked in Turkey with Ninette de Valois.[66]

In March 1950, Farron was thrilled when George Balanchine came to London to stage Ballet Imperial (1941): she never forgot the rehearsal in which Balanchine sat down at the piano and played the entire score (Tchaikovsky’s second piano concerto).[67] (We can assume Balanchine was showing off: he knew well that none of the British company’s choreographers had that kind of musical skill.) In the April 1950 premiere at Covent Garden, it was she who led the corps onstage at the start of the third movement - which she later referred to as her favourite bit of dancing in her entire career.[68] The younger dancer Valerie Taylor recalled how she came on one after Farron: “and there was so much for me to learn from the way Julia used her feet and her eyes.”[69]

In 1950-1951, she and “Rod” traveled with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet on its second tour (her first) of North America. This was an extremely taxing one, lasting five months, often with one-night stands in some cities followed by nocturnal train journeys to the next city. These tours, few as long as five months, became a pattern, occurring either every two years or even two years in succession. They brought remarkable revenue to the Royal Opera House Covent Garden (which sometimes sent the ballet company off for another American tour chiefly to subsidise its operas productions); on one occasion, the ballet company was even congratulated in the House of Commons for bringing in income to the United Kingdom.

Back at Covent Garden, Farron also danced two performances of the notoriously taxing, grand ballerina role of Ballet Imperial in March-April 1951[70], a role hitherto danced at Covent Garden by Margot Fonteyn, Moira Shearer, and Violetta Elvin. “It must have been Fred who cast me in the role: Violetta Elvin and others were ill or injured, and Madam was away somewhere – she’d never have allowed me to do it. I did feel the grandeur of that role amid that décor by Eugene Berman.”[71] The designer Sophie Fedorovitch wrote to Farron how promising she found her performance; Farron treasured this letter.[72]

In later years, she and Rodrigues would reflect on the leading ballerinas of that time. She recalled the mood onstage in Le Lac des cygnes when Odile entered to perform her famous fouetté turns: when Fonteyn did so, you could feel the company leaning subtly forward, always wishing her well in a step that was no congenial to her; when Moira Shearer performed it, the company leant back, as if uninvolved. Shearer, however, was one of what Rodrigues called “the bandbox ballerinas,” who created an aura of high elegance offstage as well as on. He would also say that he, sitting on the throne in the final act of The Sleeping Beauty, could see better than anybody else that, in the famous diagonal of sixteen petit développés, Fonteyn’s entire back was engaged, making the crescendo of accumulating arms gestures more full-bodied than the audience ever knew. Another dancer Farron and he admired was the young Svetlana Beriosova: to him, she was “the last of the bandbox ballerinas”.[73]

Farron had always danced in ballets by Ninette de Valois; in February 1950, she created the role of the Lady Belerma in de Valois’s last creation for the company, Don Quixote (to a new score by Roberto Gerhard). Subsequently during the 1950s, she created roles for another female choreographer, Andrée Howard: she was Hannah in A Mirror for Witches (1952, to commissioned music by Dennis ApIvor) and a tarantella dancer in Veneziana (1953).[74]

Ashton used Farron in many roles. In Cinderella (1948), she frequently danced the Fairy Godmother, a role created on Pamela May. She was one of the three Nymphs of Pan in his 1951 Daphnis and Chloë: their trio as the end of the first scene, as David Vaughan wrote in his 1977 study of Ashton’s ballets, conjured a sense of the numinous.[75] Farron also soon danced the role of the seductress Lykanion, one of several anti-heroines she made effective (the role had been created by Violetta Elvin): Lykanion’s pas de deux with Daphnis contains Ashton’s most poetic depiction of the sexual act, even showing the moment of female orgasm throughout the whole body. Decades later, when her former student Genesia Rosato played Lykanion, Farron showed her how she had made her exit at the end of that scene, pausing to bite the knuckle of her finger gleefully and then flourishing that arm as she departed.[76] Later in spring 1951, Farron was a Shepherdess in Ashton’s Tiresias, his final collaboration with Lambert, who conceived and composed the ballet.[77] Lambert – an advanced diabetic as well as a serious drinker - died six weeks after the premiere. In September-December 1952, Farron created two further roles for Ashton – among many other roles - the role of the irate goddess Diana in the three-act Sylvia and the exuberantly fleet-footed Neapolitan dance in the ballroom scene of Swan Lake (a new production), both in 1952 and both still danced today. When Ashton had finished making the Neapolitan Dance, he invited the whole company to watch it.[78] Live, silent film (taken by Victor Jessen) exists in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts of Farron and Alexander Grant (and other early casts) in the Neapolitan Dance[79]; it always brought the house down, often winning more applause than Prince Siegfried did for his solo in the same act.

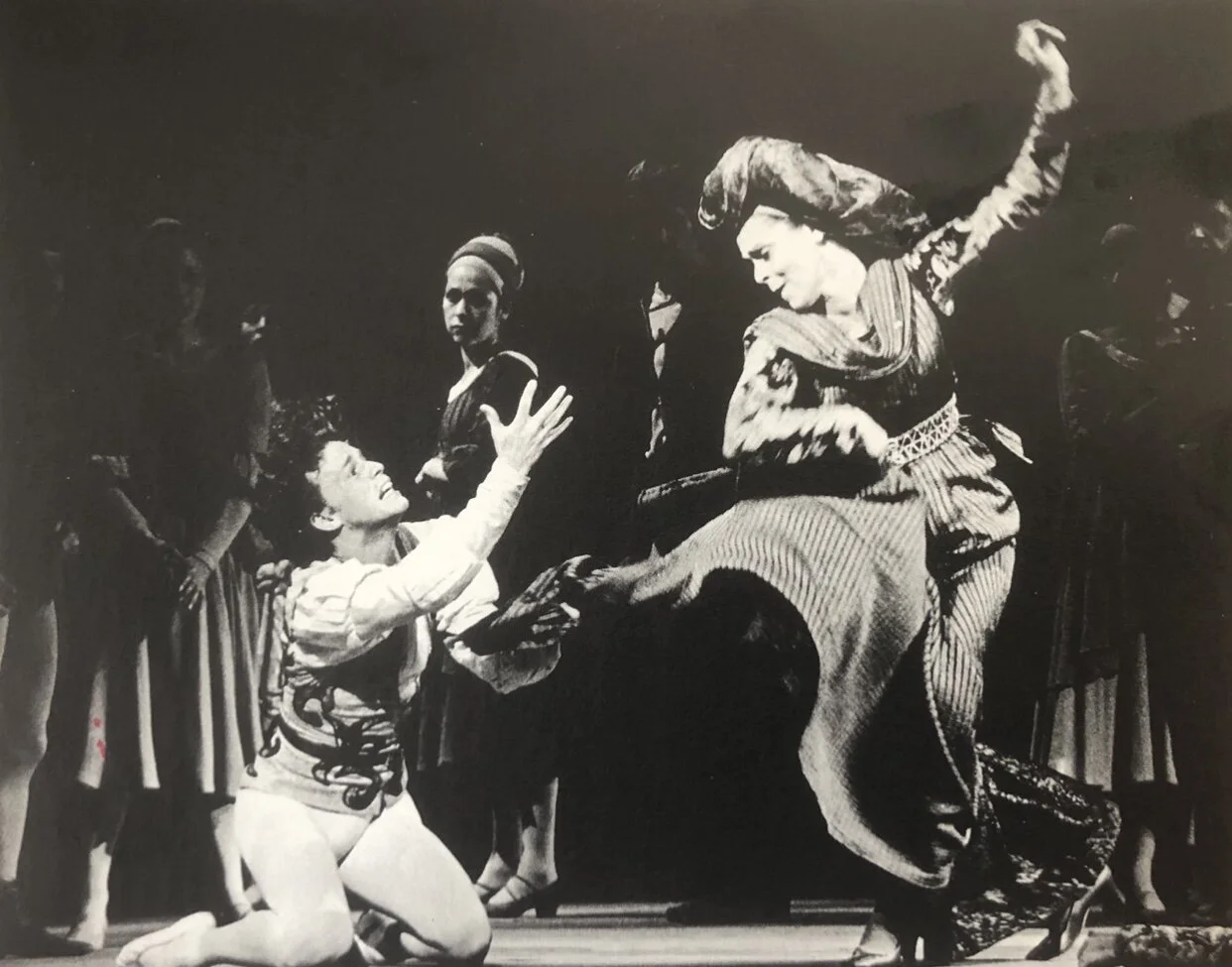

During the 1950s, the dancer John Cranko, South African like Rodrigues, emerged as a successful choreographer. He used Farron a number of times, notably to three musical premieres. In 1955, she danced a solo in dances he made for Michael Tippett’s first opera, The Midsummer Marriage (the singers included Joan Sutherland, Oralia Dominguez, and Richard Lewis; the designs were by Barbara Hepworth). In 1957, she was the anti-heroine Belle Épine in Benjamin Britten’s and Cranko’s three-act creation The Prince of the Pagodas. And in 1959, to a new score by Mikis Theodorakis, she created Jocasta in Cranko’s Antigone, the heroine’s mother and grandmother. Beriosova danced the heroine in both these ballets.[80]

Farron - even though she went on dancing lyrically poetic roles, such as the Prelude in Mikhail Fokine’s Les Sylphides (1909) throughout the 1950s – kept developing her capacity for depicting psychologically jagged characters. Having created the anti-heroine of one three-act score in Pagodas in 1957, she created another in Ondine, choreographed by Ashton to a commissioned score by Hans Werner Henze. Here she was Berta, the antithesis to Margot Fonteyn (for whom Ondine became the role she most loved[81]). Farron revealed the complexity of both Belle Épine and Berta, with startling flashes of anger and venom amid dignity and sensuality.

Farron had been a full-time professional dancer since 1936. When she heard the company was visiting Russia in 1961, when she would have completed twenty-five years with the company, she knew that would be an ideal moment to retire. Not yet forty, she said to de Valois, “I’ve been here an awfully long time.” “Yes, you have,” said Madam. “I’ve been here for over 25 years, said Farron.” “Yes, indeed,” said Madam. “I think I ought to retire,” said Farron. “Absolutely right,” said Madam.[82] Farron did so when the company returned to Covent Garden: a photograph shows her taking a solo bow – otherwise unknown - after the Neapolitan Dance in Lac des cygnes, nine years after she had created it.

The teacher Winifred (“Fanny”) Edwards, a former member of Anna Pavlova’s company and longterm member of the staff of the Royal Ballet School, said to Farron at this moment “When are you going to teach?” Edwards kept insisting “You must.” – and taught her the whole of the R.A.D. syllabus.[83] The chance came of going to teach at a summer school in Banff, in the Canadian Rockies. Now it was Rodrigues (“Rod”) who said “Go.” For a long time, Farron was not keen on the prospect; but she recalled in 2016 how she had been standing in a grocer’s shop when suddenly it came to her, “I do want to go to Canada to teach.” She went off happily.[84] Edwards pushed Farron to keep going with the R.A.D.. It was at that time, 1962, season she selected a small number of Royal School School students for demonstrations, one of whom, Gail Thomas (Gail Monahan) was to remain a devoted friend until Farron’s death.

After that, Farron began to teach full-time at the Royal Ballet School – in the Upper School at Talgarth Road, usually with the final year of students. There she helped to shape generations of dancers, including such future ballerinas as Leanne Benjamin, Bryony Brind, Fiona Chadwick, and Alessandra Ferri. Enthusiasm, thoughtful analysis, and humour were part of her teaching style: plasticity of the upper body, spruce footwork, and imaginative theatricality were her objectives. For innumerable Royal Ballet School students, Pamela May and she were their favourite teachers: they made lessons fun. Farron perhaps surpassed May in her way of motivating students who were having problems and whom she helped to turn them into valuable dancers. (Genesia Rosato, who later inherited a number of Farron’s roles and danced with the Royal Ballet for almost forty years, was one of these artists.[85])

Just before his eightieth birthday in 1984, Ashton was asked about a central conundrum of the Royal Ballet. Its classical teaching was shaped by de Valois, who made demi-character ballets that were not fully classical, whereas he, whose ballets were profoundly classical in vocabulary, style, and construction, did not teach. Amid the points he made in reply, Ashton pointed out that in May and Farron the Royal Ballet School had two dancers who, fully knowing what he liked in dance, passed on his style to their students.[86]

In 1965, Kenneth MacMillan brought Farron back to the stage in 1965 in his new three-act production of Romeo and Juliet. (Ashton was now the Royal Ballet’s director.) She was Lady Capulet, married here to her old colleague Michael Somes: she continued to play the role, also on some tours of America, until 1976. Even in casts led by Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev or Lynn Seymour and Christopher Gable, Farron made a searing impression, above all in the outrage with which she lamented the death of Tybalt. (Gable singled her out as the epitome of the acting brilliance of Royal Ballet style.[87] She herself said that Lynn Seymour helped her find how to achieve Lady Capulet’s emotion for the lament.) She continued in the role until at least 1976. Without returning to pointwork or full dancing, she played other roles in these years, such as Bathilde in Giselle. And in 1968 she added a new one, playing Carabosse in the premiere of Peter Wright’s new production of The Sleeping Beauty with designs by Lila de Nobili, with supplementary choreography by Ashton. (As she made a dramatic exit through a trapdoor, she shrieked so loudly that Ashton said to Wright, “Do tell Julia to shut her trap.”[88])

In working with the Royal Ballet School she often drew from her memories. In 1980, she supervised a School performance of Ashton’s Les Patineurs (1937), in which she had seen the premiere and danced three or more roles. At the start of the pas de trois, her Blue Skater wobbled above the waist as he summoned his two female colleagues to the front with battements sue le cou de pied. The critic David Vaughan, who had published his definitive study of Ashton’s work and was a close observer of the ballets in performance, was delighted (the wobble heightened the illusion of the dancer’s fallibility on ice), but asking her about this. Farron recalled the role’s originator, Harold Turner as she replied: “Oh, that was Harold - I could never forget that.”[89] Her memory was often vivid, accurate, and detailed but she was also good at saying “I don’t remember” with her customary frankness. She was fascinated to work again with Ashton on School performances. In 1981, she prepared three girls as Lise in La Fille mal gardée; to her surprise, Ashton chose the shyest, Sandra Madgwick – seemingly the one least like the role but the one whose dance qualities he could see would bring her inner character to the surface. Sure enough, Madgwick’s coloratura technique and songbird-like naturalness of dancing suited Lise and many other roles in her subsequent career.[90]

Farron’s teaching career reached a climax when she became Director of the Royal Academy of Dance (then the Royal Academy of Dancing) in 1983; she held the post until 1989. Though based in London, the Academy, founded in 1920, establishes standards for teaching from Canada to Hong Kong.

Despite her many friends and her keen, capacious memory, Farron did not live unduly in the past. Well aware that most ballets lose their patina after a generation or two, she often questioned whether some of them should be revived at all. She also became skeptical about the supposedly excellent memories of dancers. In 1987, Ashton and others were involved with reviving his 1936 ballet Apparitions, last danced in its entirety in 1953, for English National Ballet. Farron recalled ten years later “There were six of us at the Coliseum: who’d all danced the ballroom scene dozens of times between the 1930s and the 1950s – and we each of us had a different memory of how the choreography went! Hopeless.”[91] <81> Sometimes she was exasperated when researchers knew too little about their subjects, but she took immense pleasure when young people showed that they were well acquainted with their dance history, as when the young critic Zoë Anderson, preparing her book “The Royal Ballet - 75 years” (2006) consulted her in 2004. When she was taken in 2001 to see Mark Morris’s L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato at the Coliseum, she was full of wonder, and left the theatre speaking of how she might describe it all to her husband, who was no longer well enough to leave home. (He died the next year.)

In her eighties, now a widow, she moved to Gloucestershire to live close to her son’s country home. A number of dance friends went to visit her there; she kept in touch by many more by telephone, some of them very frequently. Her eyesight began to deteriorate; her heart gave her trouble in her final years. Now and then, commemorative ceremonies for Ashton, de Valois, or Fonteyn led her back to London. On one such occasion, she and her old friend Pauline Clayden shared a hotel bedroom, and found themselves helpless with laughter as they negotiated the difficulties of changing clothes in old age.[92]

Farron is survived by her son, Christopher Rodrigues, by two grandchildren, and by a great-grandchild, another Christopher: she spoke of them all with enthusiastic interest. She is also survived by many roles she created, from Pepé to Lady Capulet, and by innumerable former students.

@Alastair Macaulay 2021.ix.07, incorporating material from his obituary of Julia Farron for the New York Times.

NOTES

1. Was Julia one of the pawns in Ninette de Valois’s ballet Checkmate in 1937, with its commissioned score by Arthur Bliss? I do not know.

2. Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

3. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

4. We believe this was in 1934, but some say 1931. Julia later said that the scholarship money went to the other student, who did not in the event have a career of note.

5. Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

6. The Vic-Wells Ballet was sometimes known as the Sadler’s Wells Ballet early on. It had never performed much at the Old Vic, and perversely, it only became known as the Sadler’s Wells Ballet once it left Sadler’s Wells and moved to Covent Garden in 1946. In 1956, it became the Royal Ballet.

7. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

8. (During the 1939-1945 War, a popular alternative version of the Wedding Bouquetscore developed, with Constant Lambert as the Narrator speaking Stein’s words. This version has generally been adopted since Ashton’s death, although Ashton certainly preferred the choral version, which was used in all the 1980s Covent Garden performances in his lifetime.)

9. Obituary for Julia Farron, “The Times” (UK), July 19, 2019.

10. Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

11.Information from Christopher and Priscilla Rodrigues, July 2019.

12.Zoë Anderson, The Royal Ballet – Seventy-Five Years (2005).

13. Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

14. Ibid.

15.Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

16. Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

17. Beth Genné, “Creating a Canon”, Dance Research, 1997-1998.

18. Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Pamela May, 1997-1999, and Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

19. See Covent Garden database, information for 2 February 1939 gala performance.

20. Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

21. See Covent Garden database, information for 2 February 1939 gala performance.

22. Ashton, Dancing Times.

23. Obituary for Julia Farron, “The Times” (UK), July 19, 2019.

24. CD, Constant Lambert conducts Ballet Music, Ssdler’s Wells Orchestra, Celeste Catalogue, SOMMCD 080 2008.

25. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

26. Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

27. Farron, conversations with Alastair Macaulay, 1997-1999.

28. Cupid and Psyche: http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/cupid.html

29. Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

30. Especially in 1997, she invited me to some of those lunches. We were preparing a “Vic-Wells” weekend at the South Bank that summer. Julia was instrumental in introducing me to many of the Vic-Wells dancers who survived.

31. Dale to Macaulay, summer 1997.

32.Margaret Dale and Julia Farron to Macaulay, 1997.

33. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

34. Julie Kavanagh, Secret Muses – the Life of Frederick Ashton, Pantheon, US, 1997.

35. Margot Fonteyn, Autobiography, W.H.Allen, 1975.

36. Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

37. Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

38. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

39. Farron to Gail Monahan and Alastair Macaulay, 1998.

40. Pamela May, conversations with Alastair Macaulay, 1997-2000.

41. Joan Seaman to Alastair Macaulay, October 1999.

42. Margaret Dale and Julia Farron to Macaulay, 1997 and 1999.

43. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

44. See Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

45. Covent Garden database.

46. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2003.

Ashton, The Wanderer, http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/wanderer.html

and The Quest http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/quest.html

47. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2003.

48. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2003.

49. Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

50. Julia Farron and Pamela May, conversations with Alastair Macaulay and Gail Monahan, 1996-2000.

51. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

52. Margaret Dale and Julia Farron to Macaulay, 1997.

53.Phrosso Pfister, conversation with Alastair Macaulay, 1997.

54. Julie Kavanagh, Secret Muses – the Life of Frederick Ashton, Pantheon (US), 1997.

55. Ninette de Valois, letters to Joy Newton, Royal Ballet School library.

56. Mary Anne de Vlieg, conversation with Macaulay, 1980.

57. See Covent Garden Database.

58. Mam’zelle Angot http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=2447&row=1 And see Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

59. Donald of the Burthens. http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/production.aspx?production=3834&row=0

60. See Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

61. Farron and Rodrigues paired in The Sleeping Beauty. See Covent Garden 21 February 1951 http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=14075&row=5

and in “Swan Lake” 26 March, 1951: http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=14897&row=9 .

62. Farron and Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-1998.

63. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2000

64. Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997, 1998.

65. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2000.

66. Farron and Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2000.

67. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2007.

68. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2007.

69. Valerie Taylor Barnes, conversations, 2007-2010.

70. The ballerina role in Ballet Imperial: 30 March and 7 April, 1951: http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=14905&row=9 .

71. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2007.

72. Farron conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2007.

73. Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-1999.

74. Covent Garden database: Don Quixote http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11001&row=0

; Mirror for Witches http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=12136&row=0; and Veneziana http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11881&row=0.

75. David Vaughan, “Frederick Ashton and his Ballets”, first edition, A.& C. Black, 1977.

76. Genesia Rosato, conversation with Macaulay, July 14, 2019.

77. Tiresias, Covent Garden database.

78. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

79. The Victor Jessen film of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet production of Le Lac des Cygnes was assembled piecemeal from footage of multiple performances on the company’s North American tours between 1949 and 1956. Farron can be seen (among other casts) in the Neapolitan dance; she is also clearly seen in the Act One Waltz pas de six, also made by Ashton for the 1952 production (Farron was second cast; both casts are seen).

Victor Jessen also filmed the Sadler’s Wells production of “The Sleeping Beauty” in the same years, again with composite casts. Farron, together with Pamela May and June Brae, is seen as the Queen.

80. Covent Garden database. http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/production.aspx?production=1472&row=0 and http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11845&row=0 and http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11965&row=0

81. Fonteyn, Autobiography.

82. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

83. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

84. Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

85. Genesia Rosato, interview for Voices of British Ballet, 2015.

86. Ashton interview with Alastair Macaulay, “Dance Theatre Journal,” September 1984.

87. See Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

88. See Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

89. I was present for this conversation between Farron and Vaughan. Vaughan and I often mentioned this wobble, which finally became incorporated into the Sarasota Ballet’s tradition of Les Patineurs in 2008 and subsequently. I was able to tell Farron that her memory had finally bnorn further fruit.

90. Farron, speaking on a panel at the Following Sir Fred’s Steps Ashton conference, Roehampton Institute, 1994.

91. Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1977-2007.

92. Farron, conversation with Macaulay, c.2012.

Thanks to Christopher and Priscilla Rodrigues, Meredith Daneman, and, above all, Gail Monahan.

[1] Was Julia one of the pawns in Ninette de Valois’s ballet Checkmate in 1937, with its commissioned score by Arthur Bliss? I do not know.

[2] Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

[3] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016

[4] We believe this was in 1934, but some say 1931. Julia later said that the scholarship money went to the other student, who did not in the event have a career of note.

[5] Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

[6] The Vic-Wells Ballet was sometimes known as the Sadler’s Wells Ballet early on. It had never performed much at the Old Vic, and perversely, it only became known as the Sadler’s Wells Ballet once it left Sadler’s Wells and moved to Covent Garden in 1946. In 1956, it became the Royal Ballet.

[7] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[8] (During the 1939-1945 War, a popular alternative version of the Wedding Bouquetscore developed, with Constant Lambert as the Narrator speaking Stein’s words. This version has generally been adopted since Ashton’s death, although Ashton certainly preferred the choral version, which was used in all the 1980s Covent Garden performances in his lifetime.)

[9] Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

[10] Information from Christopher and Priscilla Rodrigues.

[11] Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

[12] Zoë Anderson, The Royal Ballet – Seventy-Five Years (2005).

[13] Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[16] Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

[17] Beth Genné, “Creating a Canon”, Dance Research, 1997-1998.

[18] Ibid.

[19] See Covent Garden database, information for 2 February 1939 gala performance.

[20] Alastair Macaulay, conversations with Julia Farron, 1997-2007.

[21] See Covent Garden database, information for 2 February 1939 gala performance.

[22]. Ashton, Dancing Times.

[23] Obituary for Julia Farron, “The Times” (UK), July 19, 2019.

[24] CD, Constant Lambert conducts Ballet Music, Ssdler’s Wells Orchestra, Celeste Catalogue, SOMMCD 080 2008.

[25] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[26] Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

[27] Farron, conversations with Alastair Macaulay, 1997-1999.

[28] “Cupid and Psyche”: http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/cupid.html

[29] Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

[30] Especially in 1997, she invited me to some of those lunches. We were preparing a “Vic-Wells” weekend at the South Bank that summer. Julia was instrumental in introducing me to many of the Vic-Wells dancers who survived.

[31] Margaret Dale and Julia Farron to Macaulay, 1997.

[32] Margaret Dale and Julia Farron to Macaulay, 1997.

[33] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[34] Julie Kavanagh, Secret Muses – the Life of Frederick Ashton, Pantheon, US, 1997.

[35] Margot Fonteyn, Autobiography, W.H.Allen, 1975.

[36] Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

[37] Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

[38] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[39] Farron to Gail Monahan and Alastair Macaulay, 1998.

[40] Pamela May, conversations with Alastair Macaulay, 1997-2000.

[41] Joan Seaman to Alastair Macaulay, October 1999.

[42] Margaret Dale and Julia Farron to Macaulay, 1997 and 1999.

[43] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[44] See “Daily Telegraph” obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

[45] Covent Garden database.

[46] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2003.

Ashton, The Wanderer, http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/wanderer.html

and The Quest http://www.frederickashton.org.uk/quest.html

[47] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2002.

[48] Ibid

[49] Obituary for Julia Farron, The Times (UK), July 19, 2019.

[50] Julia Farron and Pamela May, conversations with Alastair Macaulay and Gail Monahan, 1996-2000.

[51] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[52] Margaret Dale and Julia Farron to Macaulay, 1997.

[53] Phrosso Pfister, conversation with Alastair Macaulay, 1997.

[54] Julie Kavanagh, Secret Muses – the Life of Frederick Ashton, Pantheon (US), 1997.

[55] Ninette de Valois, letters to Joy Newton, Royal Ballet School library, especially those in 1952 when New York City Ballet is dancing at Covent Garden.

[56] Mary Anne de Vlieg, conversation with Macaulay, 1980.

[57] See Covent Garden Database.

[58] Mam’zelle Angot http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=2447&row=1 And see Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

[59] Donald of the Burthens. http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/production.aspx?production=3834&row=0

[60] See Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

[61] Farron and Rodrigues paired in The Sleeping Beauty. See Covent Garden 21 February 1951 http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=14075&row=5

and in “Swan Lake” 26 March, 1951: http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=14897&row=9 .

[62] Farron and Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-1998.

[63] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2000.

[64] Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997, 1998.

[65] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2000.

[66] Farron and Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2000.

[67] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2007.

[68] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2007.

[69] Valerie Taylor Barnes, conversations, 2007-2010.

[70] The ballerina role in Ballet Imperial: 30 March and 7 April, 1951: http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=14905&row=9 .

[71] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-2007.

[72] Farron conversations with Macaulay, 1997-1998.

[73] Rodrigues, conversations with Macaulay, 1997-1999.

[74] Covent Garden database: Don Quixotehttp://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11001&row=0 ; Mirror for Witches http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=12136&row=0; and Veneziana http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11881&row=0 .

[75] David Vaughan, Frederick Ashton and his Ballets, first edition, A.& C. Black, 1977.

[76] Genesia Rosato, conversation with Macaulay, July 14, 2019.

[77] Tiresias, Covent Garden database.

[78] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[80] Covent Garden database. http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/production.aspx?production=1472&row=0 and http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11845&row=0 and http://www.rohcollections.org.uk/performance.aspx?performance=11965&row=0

[81] Fonteyn, Autobiography.

[82] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[83] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[84] Gail Monahan, notes from conversation with Julia Farron in 2016.

[85] Genesia Rosato, interview for Voices of British Ballet, 2015.

[86] Ashton interview with Alastair Macaulay, Dance Theatre Journal, September 1984.

[87] See Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

[88] See Daily Telegraph obituary for Farron, July 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/obituaries/2019/07/19/julia-farron-teenage-star-pre-war-vic-wells-ballet-became-director/

[89] . I was present for this conversation between Farron and Vaughan. Vaughan and I often mentioned this wobble, which finally became incorporated into the Sarasota Ballet’s tradition of Les Patineurs in 2008 and subsequently. I was able to tell Farron that her memory had finally born further fruit.

[90] Farron, speaking on a panel at the Following Sir Fred’s Steps Ashton conference, Roehampton Institute, 1994.

[91] Farron, conversations with Macaulay, 1977-2007.

[92] Farron, conversation with Macaulay, c.2012.

--

@ Alastair Macaulay, 2021

1: In this 1934 photograph of the Vic-Wells production of The Nutcracker - the first production of the complete ballet in the West - Julia Farron (Clara) is the child on the far right. Photographer unknown.

2: The young Julia Farron as the Milkmaid in Frederick Ashton’s Façade (1931), a tile created by Lydia Lopokova.

3. Julia Farron as Alicia in Ninette de Valois’s The Haunted Ballroom (1934): she played the role in 1937.

4-6. Julia Farron, aged sixteen, in the fifth Prologue fairy variation (Violante, often called “the finger variation”) of The Sleeping Princess, as staged by Nicholas Sergueyev for the Vic-Wells Ballet. Due to a confusion, this fairy was wrongly named the Breadcrumb Fairy in this variation (the Breadcrumb dancer, Miettes qui tombent has the third variation). Because of Nadia Benois’s unfortunate headdress, Farron’s fairy became nicknamed the Hovis Fairy. The “broken” angle of her wrists is unusual for Vic-Wells style, and presumably was required by Sergueyev for this variation. Photograph: Gordon Anthony.

5: Julia Farron, aged sixteen, as the fifth Prologue fairy in Nicholas Sergueyev’s 1939 production of The Sleeping Princess. Photograph by Gordon Anthony, with characteristic shadow effects.

6: Julia Farron as the wrongly named Breadcrumb Fairy in the Prologue of The Sleeping Princess, 1939. Photograph: Gordon Anthony. Anthony is not often good at catching dance details, but the physicality here is remarkable.

7: Julia Farron, aged sixteen, as the Sapphire Fairy in the 1939 Vic-Wells production of The Sleeping Princess (Marius Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty, 1890). Although Tchaikovsky wrote a remarkable variation in 5/4 time for the Sapphire Fairy at Petipa’s request, it was never choreographed until 1968. Instead the Jewel Fairies’ pas de quatre was arranged with a solo variation for the Diamond Fairy, and the music for the Silver Fairy’s variation danced by the other three - Silver, Sapphire, and Gold Fairy. Photograph: Gordon Anthony.

8: Julia Farron, centre, as the Sapphire Fairy, between Jill Gregory (Gold Fairy) and Pauline Garnett (Silver Fairy) in The Sleeping Princess, 1939. Photograph by Gordon Anthony.

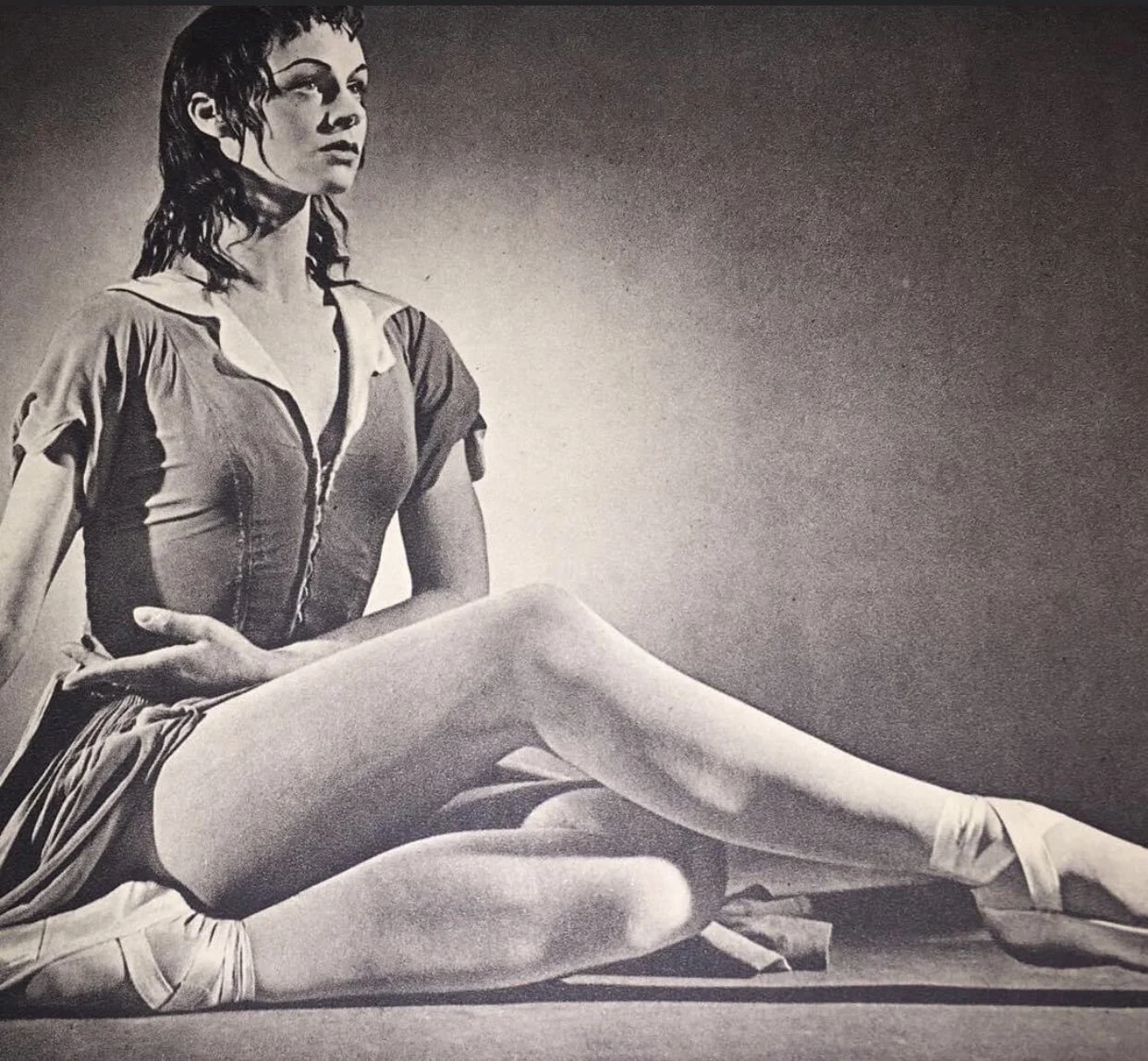

9: Julia Farron, aged sixteen, in her first important created role, Psyche in Frederick Ashton’s one-act Cupid and Psyche, to a commissioned score by Lord Berners and with scenery and costumes by Francis Rose. The first night was a fiasco, booed by the audience; there were only four performances. She went on to create many more roles, but most of them were supporting ones.

10: Julia Farron as Columbine in Mikhail Fokine’s Carnaval (1910), first danced by the Vic-Wells Ballet in 1933. Farron danced four performances of this role between 1939 and 1940.

11-13: Julia Farron as Mademoiselle Theodore in Ninette de Valois’s comic ballet about eighteenth-century theatrical fare in London, The Prospect Before Us (1940). (In 1789, Théodore created the role of Lise in the original production of La Fille mal gardée, choreographed by her husband Jean Dauberval.)

De Valois had created the role for the older Pamela May, but May’s career was interrupted by wartime childbirth and widowhood. Between 1940 and 1945, Farron danced the role forty-five times.

12: This image of Farron as Mademoiselle Theodore in de Valois’s The Prospect Before Us (1940) was reproduced on many postcards.

13: Julia Farron as Mademoiselle Theodore in de Valois’s The Prospect Before Us (1940).

14: A celebrated photograph of the 1946 opening night of The Sleeping Beauty - the reopening of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden - with the royal family in the royal box watching the Prologue. Julia Farron and David Davenport are Queen and King on their thrones.

14: Julia Farron (the Queen) in the 1946 production of The Sleeping Beauty, probably addressing Carabosse in the Prologue. Farron played the role innumerable times.

15: Julia Farron and David Davenport in the 1946 production of The Sleeping Beauty, probably in Act Three.

16: Leslie Edwards (Catalabutte), Julia Farron (the Queen), and David Davenport (the King) at the start of Act Three of the 1946 production of The Sleeping Beauty. The designs were by Oliver Messel; the production, supervised by Ninette de Valois and periodically adjusted, stayed in Covent Garden repertory until 1967 and in the Royal touring company repertory until 1970.

17-18: Two photographs taken by Henry Danton from the wings of David Davenport and Julia Farron as King and Queen in The Sleeping Beauty. Danton, now a hundred and two years old, recently rediscovered these and other photos he took - against company rules. Since he was a fairy cavalier in the Prologue and one of the four suitor princes in Act One, it’s fun to imagine him handling his camera in the wings in between appearances onstage.

18: Julia Farron as the Queen in a 1946 performance of The Sleeping Beauty at Covent Garden, photographed from the wings by her colleague Henry Danton.

19. The first role in The Sleeping Beauty danced by Julia Farron at Covent Garden after her long 1947 run of performances as the Queen was as one of Florestan’s two sisters in the Ashton-Petipa rearrangement of the Act Three Jewel divertissement. Decades later, thanks to Zoë Anderson, I bought this biscuit tin from an eBay seller in Alberta, Canada. I gave it to Julia, who laughed in recognition: “that was the first role I danced after descending the throne!”

20: Julia Farron, Pauline Clayden (the Suicide), and Leslie Edwards (a Beggar) in Miracle in the Gorbals, choreographed by Robert (“Bobby”) Helpmann in 1944 to a commissioned score by Arthur Bliss with designs by Edward Burra. “Half of what I learnt about performing onstage, I learnt from Bobby”, Farron often said.

Farron and Clayden had met as children at a performing arts school. Clayden joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1942, leaving during the 1950s after dancing a number of the roles created by Ashton for Fonteyn. She and Farron remained lifelong friends; Farron knew her as “Claudie”.

21: When the company moved to Covent Garden in 1946, Farron graduated to the role of the Prostitute in Gorbals, a role created by Celia Français, who had left the company. Farron made an immense impression on the Covent Garden audience in this role: the Prostitute, converted to belief by the Christ-like Stranger, returns to the stage with transformed body language. Although the ballet met no favour when the company took it to New York in 1949, it was performed at Covent Garden until 1958. Farron played this role forty-six times.

22: Farron as the Betrayed Girl in Ninette de Valois’s ballet The Rake’s Progress. She was the role’s main interpreter between 1944 to 1959, playing it forty-nine times.

23: Farron as the Queen in Helpmann’s Hamlet, a one-act psychodrama set to Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet overture. This was another Helpmann role created on Celia Franca that Farron inherited at Covent Garden, playing it thirty times between 1946 to 1958.

24: Farron was a new member of the Vic-Wells Ballet when it danced for a week in Paris in 1937, presenting the world premiere of Ninette de Valois’s Checkmate. (Did she dance one of the pawns?) In due course, she danced the Red Queen (seen here) thirty-two times between 1947 and 1953, and the Black Queen nine times between 1951 and 1954.

25: Frederick Ashton immediately double-cast Daphnis and Chloë when it was new in 1951 - I’d rather its female roles. Farron’s friend Pauline Clayden danced Chloë often up to 1956, when she left the company; Ashton told her that, thanks to her, it was the one ballet one which he could bear not to watch Fonteyn. He had cast Violetta Elvin as the seductress Lykanion, but cast Farron to play it opposite Clayden. (Daphnis was usually Michael Somes, with either cast.) When Elvin left the company in 1956, Farron became its chief interpreter until 1959.

Twenty years later, her former student Genesia Rosato played the role. Farron gave her a bit of business she had performed just before leaving the stage after seducing Daphnis: pausing on point, she bit the knuckle of her finger as if in secret triumph.

26: In 1952, Ashton created the three-act ballet Sylvia, casting Farron as the angry goddess Diana, who appears only in Act Three but with rage that threatens to unbalance the story. This photo by Fonteyn’s brother Felix Fonteyn shows Farron as Diana at the top of the steps to her temple. Margot Fonteyn kneels in supplication to Diana, right; her two male admirers, John Hart (Orion) and Michael Somes (Aminta), are on either side.

27: Three months after creating the role of Diana, Farron created another for Ashton, the most acclaimed part he ever made for her: the Neapolitan Dance in Swan Lake. The dance is a presto duet: Farron and Alexander Grant, both favourite dancers of Ashton’s, danced in extreme proximity to each other and at top speed. It was a sensation from its premiere onward.

28: In 1957, Farron created a three-act role, the anti-heroine Belle Épine in The Prince of the Pagodas, choreographed by John Cranko to a commissioned score by Benjamin Britten: she danced it twenty-three times. Although this production only lasted four seasons, its memory for many was in no way effaced by Kenneth MacMillan’s 1989 re-telling of the same score.

29: Leslie Edwards as the dying Oedipus and Julia Farron as Jocasta in John Cranko’s Antigone (1959).

30: Rowena Jackson (left), Nadia Nerina (centre), and Julia Farron (right) before filming a 1958 account of Les Sylphides in Hammersmith Town Hall. The television director was their old ballet colleague Margaret Dale, with whom Farron had been friends since the 1930s and with whom she remained friends into the twenty-first century

31: Julia Farron rehearsing the Prelude in Les Sylphides at the Hammersmith Town Hall in front of students, prior to filming in 1958.

32: Julia Farron as Lady Capulet in Kenneth MacMillan’s 1965 production, with Rudolf Nureyev (Romeo) kneeling at her feet after having killed her kinsman Tybalt.

33: Lady Capulet rejects the entreaties of the kneeling Romeo: Julia Farron (right) with Anthony Dowell (left).

34: Julia Farron (left) speaking with the choreographer Mary Skeaping at the Royal Academy of Dance. Photo: G.B.L. Wilson. Much later, Farron became Director of the Royal Academy of Dance between 1983 and 1989.

35: Julia Farron Rodrigues in retirement.