Tributes to George Platt Lynes (1907-1955)

The photographer George Platt Lynes (1907-1955) took fashion photographs, nude photographs (especially male), and ballet photographs. There are dance-goers today who dislike his pictures, but the exceptional terms in which the choreographer George Balanchine praised him are startling: “I consider that George Lynes synthesised better than anyone else the atmosphere of some of my ballets….. George Lynes pictures will contain, as far as I am concerned, all that will be remembered of my own repertory in a hundred years.”

Balanchine, though often memorably eloquent in spoken English, generally lacked the confidence in his written English to publish a statement or letter without assistance. On this occasion, he was writing on Thanksgiving Day 1956 in Copenhagen, a month after his wife Tanaquil Le Clercq had been afflicted with polio there. Probably his choice of words was made by Lincoln Kirstein, through whom he had met Lynes. Nonetheless Balanchine did not issue published statements without approving them; and this tribute to Lynes, who had died the year before, is of great interest to all devotees of Balanchine’s work.

Lynes’s attention to light, movement, the human figure, and drama made him a kindred spirit to Balanchine, to the painter-designer Pavel Tchelitchew (1898-1957) and to the lighting designer Jean Rosenthal (1912-1969). Of especial interest is the paragraph (plate 8) in which Balanchine says Lynes’s figures “seemed to exist in an actual aery ambience, akin to the three-dimensional vitality in sculpture…. Dance has more kinship to sculpture than to painting. Paul Valéry said that Degas did natures-mortes (still-lives) of dancers. It was not movement, physical action that interested him; it was the bouquet, the atmosphere of performance, the style. <Plate 9> I consider that George Lynes synthesized better than anyone else the atmosphere of some of my ballets.”

Lynes actually photographed Frederick Ashton’s 1934 staging of Four Saints in Three Acts before he did any Balanchine staging; but in 1935 he began to depict the American Ballet, in Balanchine’s Errante (plate 16). Once Balanchine and Tchelitchew staged Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1936, Lynes became an integral part of the Balanchine enterprise. (It’s worth noting that Cecil Beaton, a yet more celebrated photographer of the day, also photographed this Orpheus production. I wish someone would investigate the Lynes-Beaton connection.)

Kirstein had known him for many years. While Lynes and he were in their mid-teens, Lynes had been a dazzling editor through whom Kirstein had discovered the poetry of T.S.Eliot. In their early twenties, Lynes had led Kirstein to discover, in Europe, Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and Jean Cocteau, and to meet Tchelitchew.

From 1938 onward, Lynes photographed ballets made by other choreographers for Kirstein’s American Ballet Caravan. Lynes and Kirstein became part of a network of friends, many of them gay men, who also included Glenway Westcott, Tchelitchew, Cecil Beaton, and Monroe Wheeler. In December 1944, Kirstein published Photographs by George Platt Lynes as an issue of Dance Index. After the formation of New York City Ballet, Lynes photographed many of its productions.

He always worked in the studio. When the ballets were by Balanchine, the choreographer came to the studio to supervise the session. Balanchine nonetheless knew that the photographs were not his work but Lynes’s.

In early 1955, Lynes learnt that he had advanced lung cancer. He was already in contact with the sexologist Alfred Kinsey, whose 1948 and 1953 reports on male and female sexuality had shaken up American society; and he arranged for the Kinsey Institute to take the majority of his photographs, many of which would have been considered pornographic and might have been destroyed.

Lynes died near the end of 1955. Kirstein soon began to commission and collect tributes to him for a commemorative New York City Ballet souvenir program. When that forty-page program was published in 1958, after the premieres of Balanchine’s Agon (1957) and Stars and Stripes (1958), it served a second purpose, celebrating City Ballet’s active repertory while honouring Lynes. The tributes to Lynes (plates 7-14) make quite an artistic galaxy; although the one by the superlative critic Edwin Denby is not Denby’s finest work, it’s rare, having never been included in any Denby anthology. Four mistakes leap out to my eye: Lynes’s death is given as 1956; the photograph of Balanchine is also given as 1956; Tchelitchew’s name is misspelt; and Kirstein’s makes his habitual but erroneous claim that it was through Lynes and Tchelitchew that he met Balanchine. (Kirstein’s 1933 diaries show that, although he hoped to meet Balanchine in Paris through Tchelitchew, he failed to do so. Instead he was introduced to Balanchine in London by Frederick Ashton.)

The cover photograph of Maria Tallchief and Nicholas Magallanes in Symphony in C alone establishes Lynes’s greatness as a photographer. Sculptural qualities are charged with intense energy. Line and shape become high drama as Tallchief’s musculature claims light and air at full stretch.

Tuesday 10 August

1: Maria Tallchief and Nicholas Magallanes in George Balanchine’s Symphony in C. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. Cover image of the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

2: George Platt Lynes. Photograph by Cecil Beaton. This is the only photograph not by Lynes in New York City Ballet’S 1958 souvenir program.

3: George Balanchine, by George Platt Lynes. Lynes died in 1955, but the photographing is dated as 1956 by New York City Ballet’s 1958 souvenir program, which also gives 1956 as the year of Lynes’s death. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

4: The introductory page of New York City Ballet’s 1958 souvenir program. Many details here are of interest: Lynes’s death is wrongly dated as 1956; George Balanchine, later named as Ballet Master, is here Artistic Director, with Lincoln Kirstein as Artistic Director; Jerome Robbins is titled Associate Artistic Director. Although Betty Cage is high up the list of New York City Ballet staff, as General Manager, she is not named here. Leon Barzin, the company’s founding Musical Director since 1948, however, is named here, but not elsewhere, perhaps because Robert Irving became the company’s Music Director in 1958. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

5: Child dance students and George Balanchine in the late 1940s; the little boy is Edward Villella. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

6 George Balanchine, Francisco Moncion, and Tanaquil Le Clercq. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

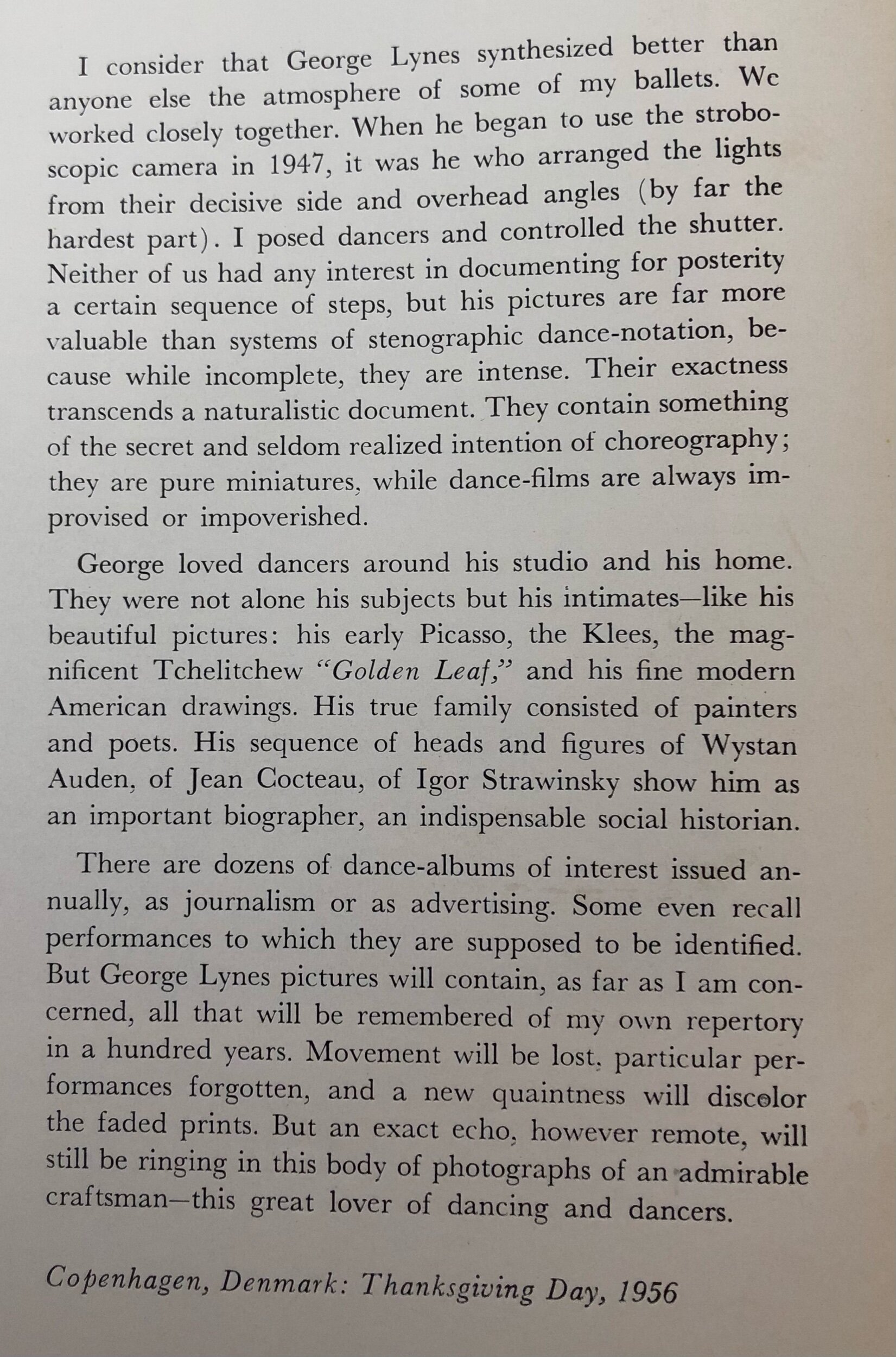

7: Column 1 of George Balanchine’s tribute to George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

8: Column 2 of George Balanchine’s tribute to George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

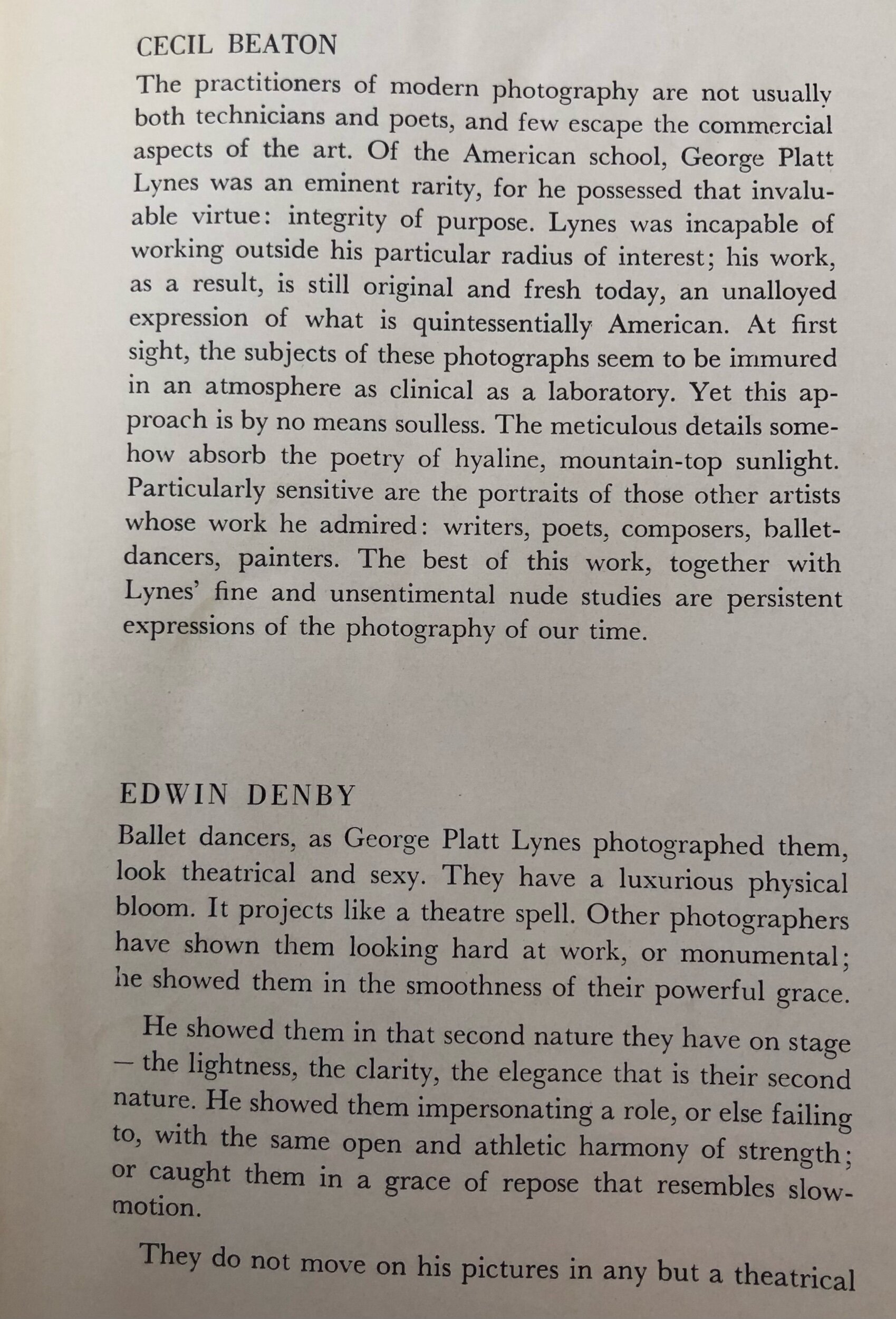

9: Tributes to George Platt Lynes by Cecil Beaton and Edwin Denby (part 1). Denby’s words on Lynes have not been republished in any Denby anthology. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

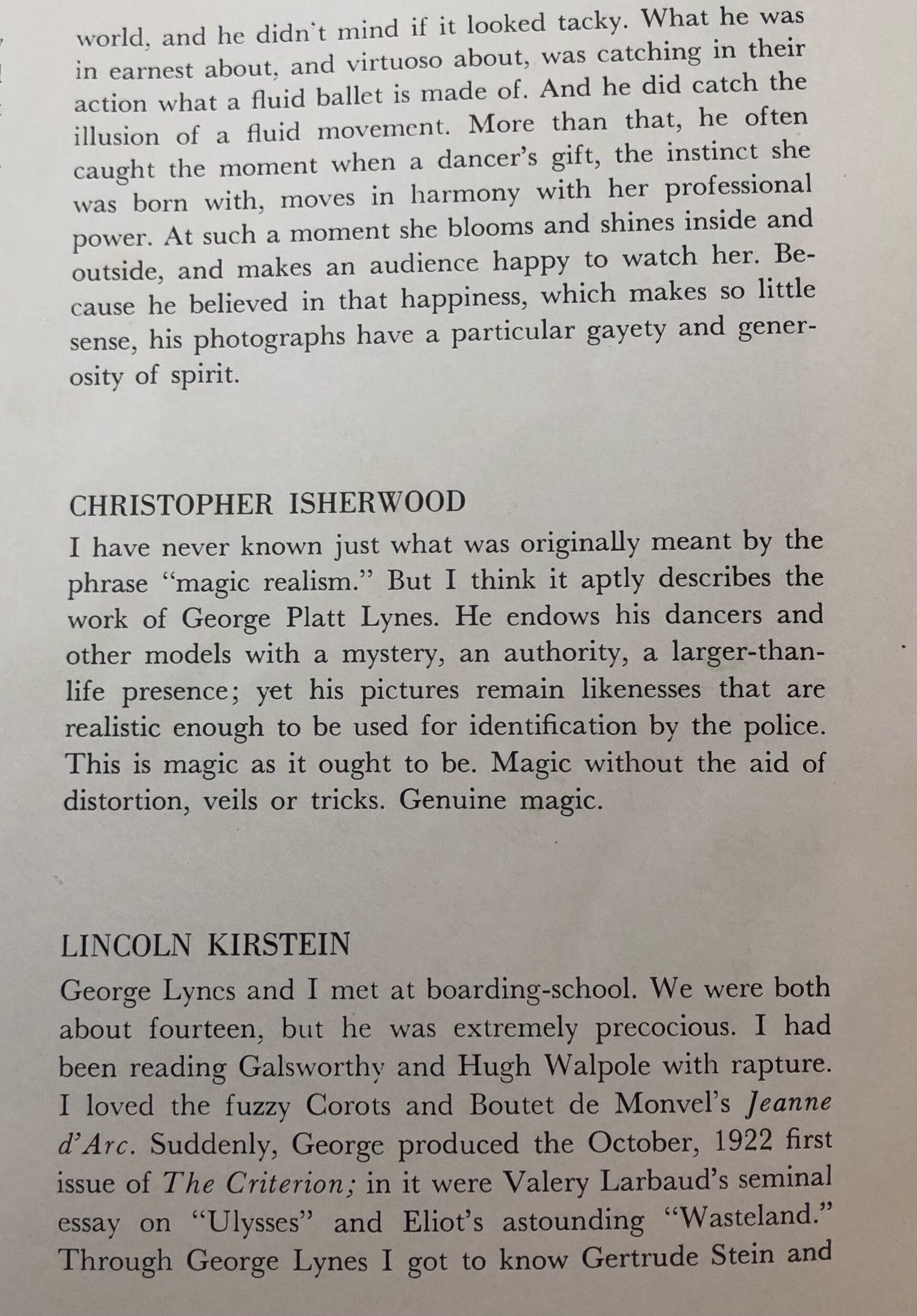

10: Part 2 of Edwin Denby’s tribute to George Platt Lynes; one by Christopher Isherwood; and Part 1 of Lincoln Kirstein’s. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

11: Tributes to George Platt Lynes from Lincoln Kirstein (part 2), John Martin, Marianne Moore, and Edith Sitwell. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

12: Tributes to George Platt Lynes from Edith Sitwell (part 2), Osbert Sitwell, Pavel Tchelitchew (who had died in 1956 and whose name is mis-spelt), and Carl van Vechten. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

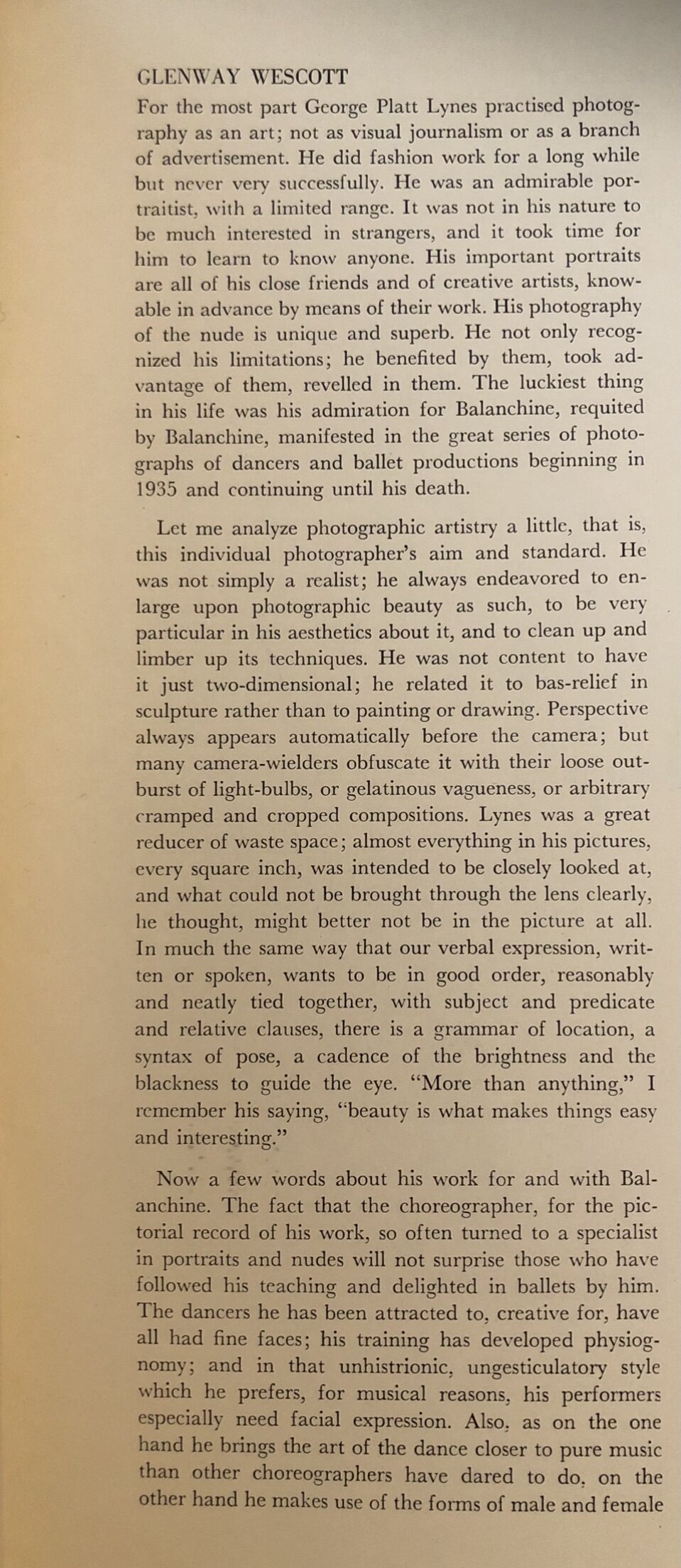

13: Column 1 of Glenway Westcott’s tribute to George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

14: Column 2 of Glenway Westcott’s tribute to George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

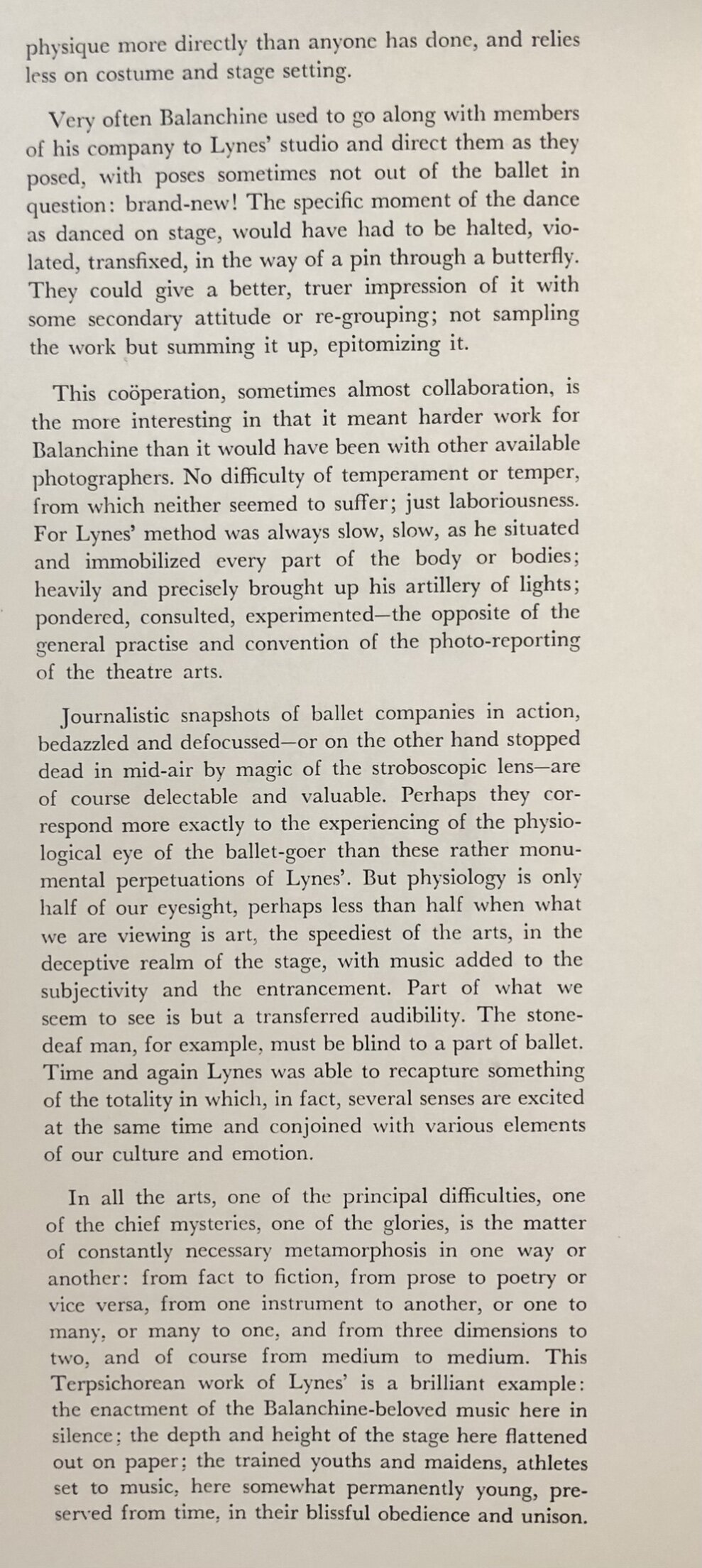

15: Lew Christensen in the title role of George Balanchine’s Apollon Musagète (Apollo). Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

The implication is that Apollo is looking up to his father Zeus on Mount Olympus. Balanchine, who supervised all Lynes’s photographs of his work, coached all his Apollos to understand that the eye of Zeus is on Apollo throughout this ballet.

16: George Balanchine’s Errante, with Kathryn Mullowney (left), Tamara Geva (centre), William Dollar (right). Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

Mullowney was the “Dark Angel” in George Balanchine’s original 1934 and 1935 productions of Serenade: Geva, Balanchine’s first wife, had preceded him to America, winning fame in her own right; Dollar was the male dancer Balanchine most admired of those who studied at the School of American Ballet in 1934-1935 and became a founder member of the American Ballet in 1935.

17: Lew Christensen as the Pump Attendant in his own Filling Station (1938), a ballet choreographed to a commissioned score by Virgil Thomson and a scenario by Lincoln Kirstein, with designs by Paul Cadmus. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

18: Jacques D’Amboise as the Pump Attendant in a 1950s revival of Lew Christensen’s Filling Station (1938). Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

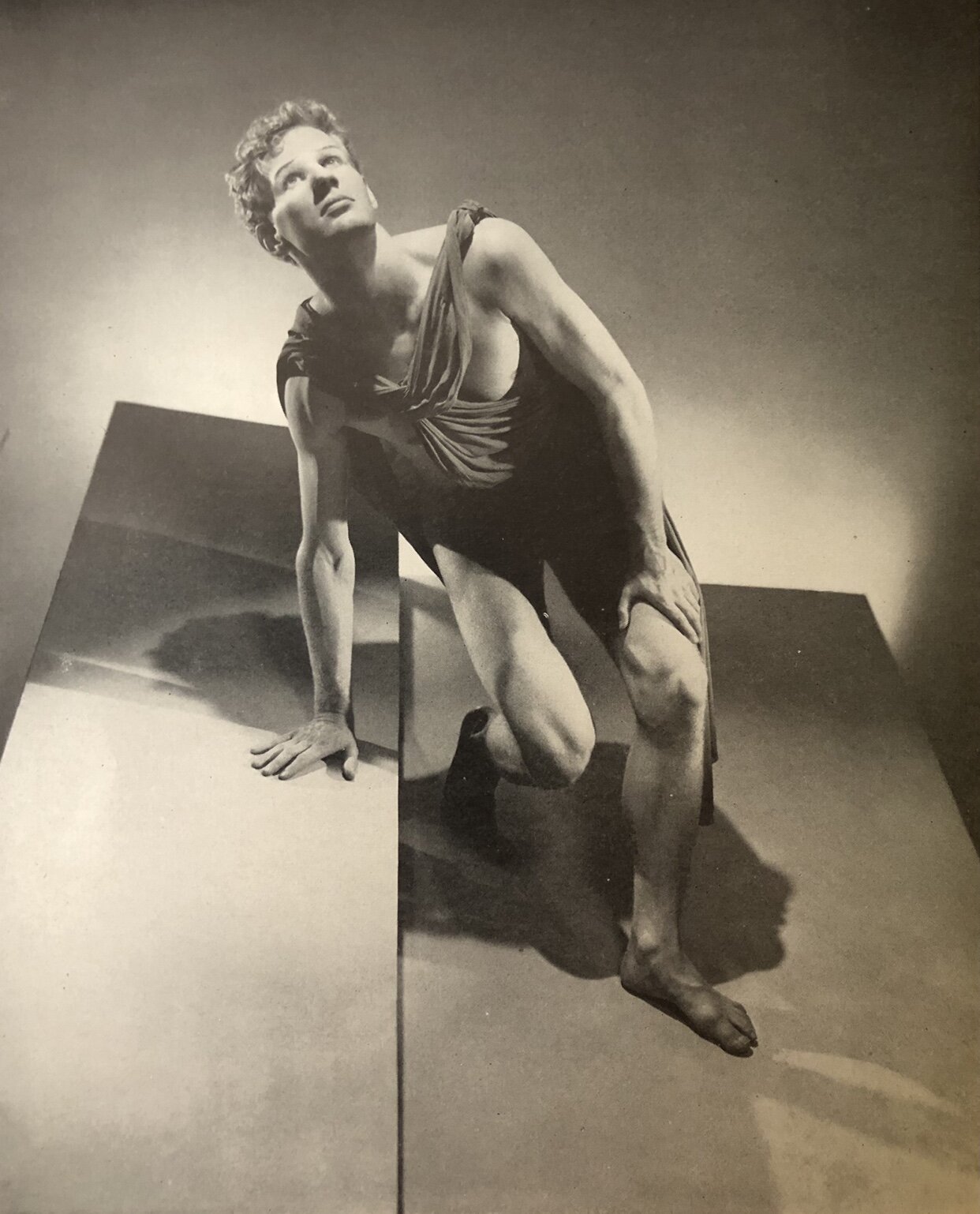

19: Hugh Laing and Nora Kaye in New York City Ballet’s 1951 production of Antony Tudor’s Lilac Garden. Tudor had choreographed it as Jardin aux lilas in 1936 for Ballet Rambert in London, with Laing in the same role.

In 1951, Tudor, Kaye, Laing, and Diana Adams (Laing’s wife) transferred from American Ballet Theatre to City Ballet. Tudor, Kaye, and Laing returned to Ballet Theatre in 1953; Adams remained with City Ballet for the rest of her stage career.

Balanchine later used this decor for Lilac Garden in 1961 for his own Raymonda Variations.

20: The original cast of George Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco (1941). Marie-Jeanne and William Dollar (left) in the second movement; Lorna London and June Graham of the corps de ballet are on the right. The costumes are by Eugene Berman. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

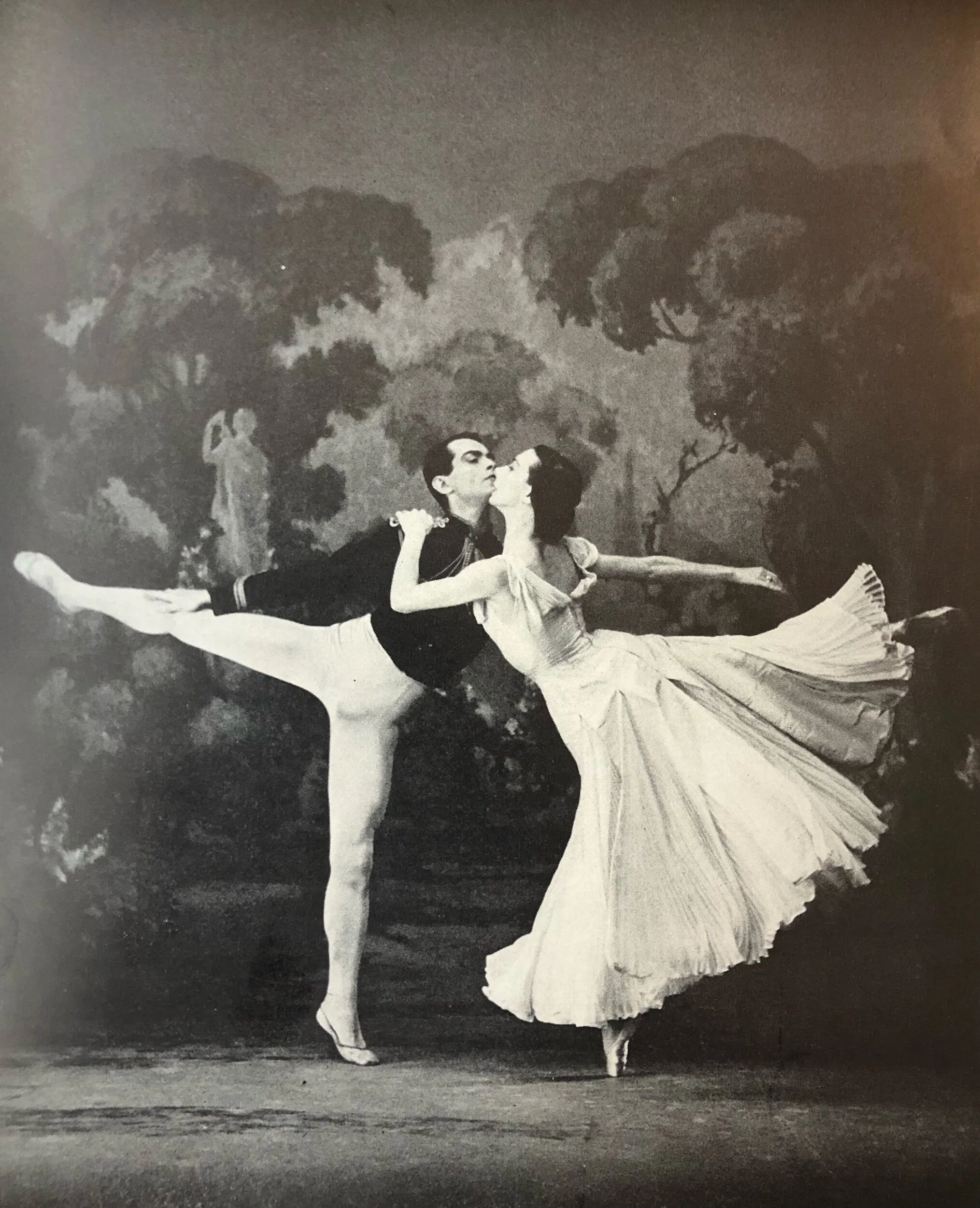

21: George Balanchine’s Orpheus (1948), with Nicholas Magallanes (Orpheus) and Maria Tallchief (Eurydice). Designs by Isamu Noguchi. The ballet was originally produced for Ballet Society at New York City Center Theater; Morton Baum of City Center found it so revelatory that he invited Lincoln Kirstein and Balanchine to institute New York City Ballet, which presented it later that year in its opening program.

Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

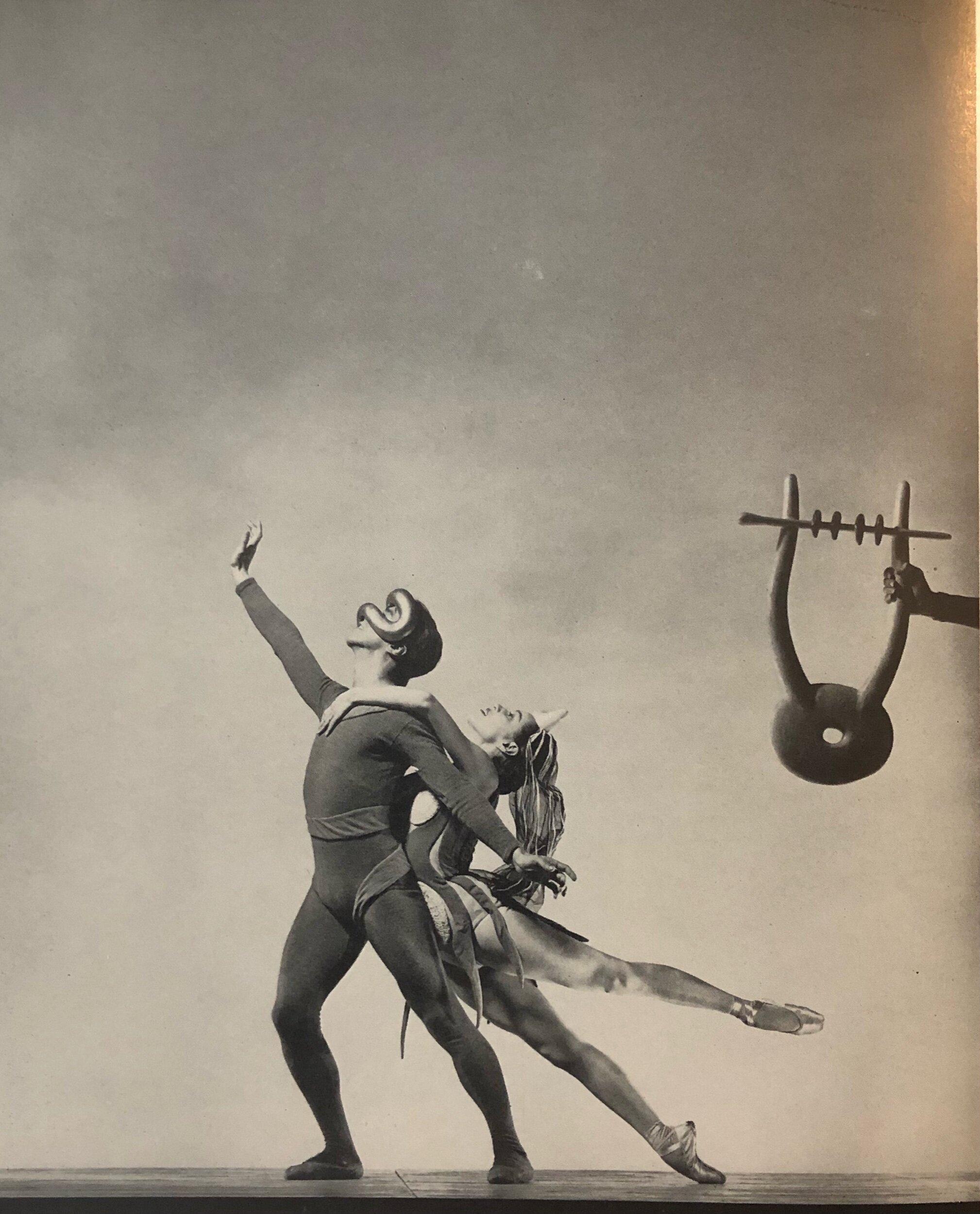

22: George Balanchine’s original production of Firebird (1949), with designs by Marc Chagall. Maria Tallchief and Francisco Moncion as the Firebird and Ivan Tsarevich. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

23: Tanaquil Le Clercq and Jerome Robbins in the first movement of George Balanchine’s Bourrée Fatntasque (1949), which had its premiere only four days after Firebird. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

24: Nicholas Magallanes as the Poet of Frederick Ashton’s Illuminations (1950), with four of the pierrots who populate this ballet. Ashton created this for New York City Ballet. Designs are by Cecil Beaton. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

25: Janet Reed and Herbert Bliss, the original couple of George Balanchine’s Pas de Deux Romantique, which had its premiere four days after Ashton’s Illuminations. Costumes by Robert Stevenson; music was Weber’s Concertino for Clarinet and Orchestra. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

26: Todd Bolender in The Miraculous Mandarin (1951), his own creation for New York City Ballet. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

27: Melissa Hayden in George Balanchine’s Caracole (1952), the Mozart ballet parts of which Balanchine subsequently recycled for his enduring masterpiece Divertimento no 15 (1956). The designs for Caracole were by Christian Bérard. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.

28: Tanaquil Le Clercq in George Balanchine’s Western Symphony (1954), wearing a costume designed by Karinska. Le Clercq created the fourth-movement Western ballerina role. Photograph by George Platt Lynes. From the 1958 New York City Ballet souvenir program.