Patricia Lent (Part 2) on Merce Cunningham, questions and answers 37 to 73.

Patricia Lent danced with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company from 1984 to 1993, and with Mikhail Baryshnikov’s White Oak Dance Project from 1994 to 1996. In 2002, she was invited by Cunningham to revive Fabrications (1987) for his company, a project with great success. A month before his death. Cunningham announced plans for his artistic legacy that included appointing four people to the Cunningham Trust. One of the four was Lent, who became Director of Licensing.

Lent has already answered thirty-six of my questions: see the questionnaire posted hereon February 22, 2022. Here she answers a further thirty-seven. With characteristic generosityand industry, she hopes to continue answering yet further questions at a later date. AM

AM 37. In Merce’s essay “Four Events that led to Large Discoveries”, he mentions

(i) the separation of dance from music;

(ii) the application of chance procedures;

(iii) the use of the camera;

(iv) the use of the dance computer

as the four events that opened up new dimensions for his work. When you joined the company, he was coming to the end of his remarkable collaboration with Charles Atlas [1], but moving into another with Elliott Caplan [2]. How did you feel - or how do you feel now - that the camera extended Merce’s creativity?

PL 37. I was never involved in any of the Atlas film projects – Charlie had left before I joined the company, and I left the company before he came back.

My first experience working with Merce on a video dance was in 1983 when I was still a student at Westbeth. He asked five of us (Jill Diamond, Kate Troughton, Frey Faust, Bill Young, and me) to work with him, kind of a private workshop. We were thrilled, of course. What we were working on eventually became Deli Commedia, but at that point it was just the five of us and Merce looking through a viewfinder. What comes back most vividly is how entertained and engaged Merce was – experimenting with camera space and devising vaudevillian routines with comical entrances and exits. A simple black-and-white video was made of that version, but by the time Elliot Caplan and Merce produced Deli Commedia (1985), I had joined the company, and so wasn’t part of it. There were several major film projects while I was in the company – Points in Space (1987) [3], Changing Steps (1989) [4] Beach Birds for Camera (1992) [5] – but it was during that initial pared-down student project that I first witnessed Merce’s intense and also playful engagement with the camera.

AM 38. Which Cunningham dances created for the screen do you most admire, and why?

PL 38. I’ve always loved Locale [6] and Channels/Inserts [7], but, in singling them out, I’m not entirely sure I’m distinguishing between the film versions and the stage versions. They are simply two of my favorite Cunningham dances – such bold,powerful, sweeping movement. Terrific to watch, and even more terrific to dance.

One aspect of those two films that I especially appreciate is the use of the Westbeth studio space. I have always loved watching Merce’s work in the studio, and these two films evoke that experience. Formal, yes, but also on home turf.

AM 39. Which camera adaptations of Cunningham stage dances do you most admire, and why?

PL 39. I think the first part of Beach Birds for Camera (the black-and-white segment) is stunning - for the arrangement of the dancers in the bare room, and the sense that the action is ongoing, that the viewer (via the camera) has stumbled upon the scene. It’s a wonderful hybrid of the familiar and the abstract. Now that I’ve studied and staged Beach Birds (the original dance for the stage), I have a greater appreciation for how artfully Merce and Elliot adapted that material for camera. It’s a completely different spatial arrangement.

AM 40. Charles Atlas seems to me to have been the artistic collaborator with the greatest affinity to Cunningham and even the greatest understanding of Cunningham: they were both foxy, subversive, left-field thinkers, but with the same passion for fundamental rediscovered of space and time. What did you observe of their collaboration? Do you agree or disagree with my point?

PL 40. I really don’t know Charlie well enough to comment. I never had the opportunity to see or experience Merce and Charlie working together.

AM 41. Can you say why you weren’t in Coast Zone (1983) [8]?

PL 41. I wasn’t in the company yet. I don’t think I was even an apprentice at the time of the filming.

AM 42. Coast Zone is the video dance of which Charles Atlas is most proud. Did you dance it onstage? Your memories of it?

PL 42. I never danced Coast Zone. The stage dance was only in the repertory for about a year, and I was never in it. I don’t remember much about it.

AM 43. John Cage is, of course, the most famous of Merce’s collaborators, but he himself sometimes said that he was utterly unlike Merce (but utterly like Rauschenberg). If that was true - Cage could contradict himself - it shows that he and Merce enjoyed surprising each other, working in different ways. You were there for the last nine or more years of Cage’s life.

Can you tell again the marvellous story you have told of how Cage seemed to have suggested the sections of Doubles (1984) where the stage emptied entirely?

PL 43. When Merce had finished a dance, he would often invite John to the studio to watch a run through (a rehearsal run, without music or costumes). Doubles was my second dance, so I was just learning the patterns and habits of the company.

In that dance, I did a walking duet with Karen Radford that crossed from stage right to stage left. We did it twice during the dance, the first time all the way upstage with our arms low; the second time across the front of the stage with added arm gestures and flourishes. The first time, our cue to enter came from Alan Good, who was doing a jumping phrase in a big circle around the stage. After he passed our upstage wing, but before he exited, we would take four steps onstage and begin.

After John watched the rehearsal, Merce called us into the studio and said he wanted to try something – “John gave me an idea,” or something along those lines. Merce changed our cue, telling us to let Alan fully exit, then count to 5 or 6 (Karen did the counting), and then enter. This meant the stage was completely empty for several seconds – the dance equivalent of silence. We did the same thing before our second entrance, leaving the stage empty for a few moments.

AM 44. What other signs of collaboration or suggestion or collusion did you observe between them, if any?

PL 44. For the most part, I didn’t see them collaborating because they worked independently. Once, though, during a panel discussion at Berkeley, someone in the audience asked about their approach to collaboration – essentially wondering how their way of working could even be considered collaboration. John responded (as I recall), “I do my next thing, and Merce does his next thing, and then for your convenience we do it at the same time.” That idea of “next thing” stuck with me. The idea that they were both busy artists deeply engaged with their own work, but also intimately aware of each other’s work – of each other’s last thing, current thing, and next thing.

AM 45. Cage toured with the Cunningham company almost invariably until early 1985, when he broke his wrist by falling on ice in Indiana. Do you remember that event?

PL 45. Not well, although I remember hearing about it.

AM 46. I know you don’t enjoy my asking about Merce’s sexual affairs, but I hope you understand that I just want to get things right, since all kinds of false as well as correct rumours still abound.

Within a month or two of Cage’s Indiana fall, people in MCDC observed Chris Komar visiting Merce’s hotel rooms in a way that indicated a new intimacy. It’s not for us to speculate about the sexual side of this (if any), but how do you remember the development of Chris’s involvement with Merce in 1985-1987?

PL 46. I was aware, as all of us were, that Merce and Chris were involved. I can’t put a date on when it started, and I never talked to either of them about it. My relationship with Merce was professional not personal, despite the built-in intimacies of dancing and touring. He was my boss, my choreographer.

There were a few memorable occasions, however, when Merce openly (albeit indirectly) acknowledged his relationship with Chris. In 1990, the Paris Opera dancers Wilfride Piollet and Jean Guizerix asked to learn a Cunningham dance, and it was decided that they would learn two duets from August Pace, the one made for Helen Barrow and Rob Wood, and the one made for Alan Good and me. At that time, Helen and Rob were together, Alan and I were together, and Wilfride and Jean had been together for many years. After the rehearsals at Westbeth, Merce invited us to dinner at Omen. There were eight of us at the dinner, Wilfride and Jean, Helen and Rob, Alan and me, and Merce and Chris. In the studio, it had not seemed so evident, but, sitting around the table at Omen, it felt like four couples.

There was a similar occasion not long afterward in Paris. A dinner for six after one of our shows in which Merce and Chris were one of three “couples.” As at Omen, it was not remarked upon.

AM 47. (More of same.) At some point in 1987, Cage discovered a Merce diary that gave evidence of his sexual affair with Komar. He, Cage, considered a personal break with Cunningham, something he discussed with a few intimates. Again, it’s not for us to speculate on what we don’t know. Very few people knew of this either then or later; some inaccurate rumours circulated.

But did you observe any change in behaviour between Cage and Cunningham, or between Cage and Komar, or between Komar and Cunningham at that time? (I have to ask!)

PL 47. I was both aware and unaware of these personal matters. For me, the big change was that John stopped touring with us, which I regretted. I thought that was due to the demands of his Europeras project and other professional commitments. Around the same time, Chris assumed broader responsibilities as Merce’s assistant.

AM 48. The miracle that occurred just around the time of Cage’s 1985 fall was Doubles, a work dear to us both. Am I right to say that this often has two or even three different dance rhythms coinciding, quite independent of one another? How often is this independent simultaneity a feature of Cunningham choreography?

PL 48. It happens all the time, throughout Merce’s work, at least as far back as Suite for Five (1956) and straight through Nearly Ninety (2009). That’s what’s going on in a Cunningham dance whenever several people are dancing at the same time but not doing the same thing. That possibility – of a multiplicity of rhythms and phrasings and meters (and non-meters) – is what gets opened up when the dancing and the music operate independently.

AM 49. When you began to study Merce’s notes for Doubles after his death, you found that all the solos, and the duets for two women, had been composed in various forms of a rhythmic structure, 13x13, 14x14, and so on. We now can recognise this as a compositional device Cage had used a lot in the late 1940s and early 1950s: it’s what Cage scholars call the square-root formula.

Merce’s notes for Springweather and People, 1955, show that he spent time preparing that whole extensive work in terms of 38x38, more exactly of <13+13+12> x <13+13+12>. It’s interesting that Merce reverts to this formula in 1984, decades after Cage has stopped using it. Can you explain how it works in the Doubles solos? And can you explain how Merce achieved the dance rhythm of each solo? Am I right that he used chance?

PL 49. This is much easier to demonstrate in a studio than it is to explain in writing, but I’ll do my best. As an example, I’ll use the solo that opened the dance, the one made for Lise Friedman and Cathy Kerr. That solo was structured as 13 phrases of 13 counts. For each of the 169 counts, Merce used chance to determine whether there would or would not be a shift of weight on that count (that is, a step on the left, a step on the right, a landing from a jump, or some other transfer of weight). I don’t know precisely what chance mechanism Merce used, but my guess is that he flipped a coin – “heads you shift, tails you don’t,” or something along those lines. For the Lise/Cathy solo, the result of the chance operations was that most of the 13 phrases of 13 counts had between 6 and 8 weight shifts; one phrase shifted weight on every count, and a few phrases had no weight shifts at all. This established the rhythm of the solo, which Merce recorded using numbers (to indicate a weight shift) and dashes (to indicate no shift). Merce then invented movement that corresponded to this rhythm or “score.” On the counts with no shift of weight, something else could happen – an arm gesture, for example, or a slow leg extension. So the solo began: arm circle; fall on the right leg; shift onto the left leg; arm circle. The two arm circles were “no shift” counts.

All the solos shared this underlying structure. One was 14 phrases of 14 counts, another was 16 phrases of 16 counts, and so on. For each solo, Merce’s notes include a one-page “score” laying out the complete rhythmic structure for that solo, followed by a series of pages with detailed phrase-by-phrase descriptions of the movement he invented corresponding to that rhythm. There were other subdivisions of the phrases that came into play, but that’s the basic framework.

AM 50. You’ve also shown that Merce wasn’t obsessive in following the square-root formula. In one case, he’d got halfway through when he realised the solo was already quite long enough and exhausting enough. Am I right, and, if so, which solo?

PL 50. Not exactly. There were two solos that broke the pattern, in two different ways. The solo for Neil Greenberg and Chris Komar was structured as 18 phrases of 24 counts, rather than 24 phrases of 24 counts (or 18 phrases of 18 counts). I don’t know why, but that’s how the score was laid out in Merce’s notes from the beginning before he worked with Neil and Chris.

The solo for Rob Remley and Robert Swinston was planned as 21 phrases of 21 counts, but in the end Merce taught them only the first 7 phrases of 21, and then had them run to a new place and repeat those 7 phrases again. The rest of the material was not used. This solo came at the very end of the dance, so Merce may have made this decision because he was running short on time and needed to get the dance finished. But he could have done it for an entirely different reason.

AM 51. These were some of many discoveries you found from studying the notes. You were in the original Doubles; Merce never told such things to the dancers.

I’ve seen and heard you analyse the notes for several other dances in which you created roles and in which I saw you dance. You’ve helped us all - and yourself - to understand many ways in which Merce composed this dances and other dances: amazing and wonderful. But you’ve also learnt and shown that Merce was always prepared to depart from his notes once he was in the room with the dancers. Can you give examples in Doubles?

PL 51. In my experience, Merce’s choreographic notes are best understood as plans for a dance he is going to make rather than a record of a dance he has already made. Merce’s notes typically predate the first rehearsals by weeks if not months. You could say that his notes describe a dance on the horizon.

The notes for Doubles are packed with information. But there are multiple discrepancies between the plans and the final dance. As I mentioned earlier, the Rob/Robert solo appears in Merce’s notes as 21 phrases of 21 counts, but it ended up as just 7 phrases done twice. The Alan/Joseph solo was also cut short by a few phrases, and the timing of their pauses was adjusted to work with a trio for three women that occurred at the same time. There are other similar discrepancies, as well as minor (and not so minor) differences between the movement described in the notes and the movement done in the dance.

When Merce made Doubles, he conveyed rich, detailed, nuanced information about the movement to his dancers, and he entrusted his dancers to embody and realize that information – to collaborate with him in turning his plans and intentions into a dance. He didn’t say “Okay, now I’m going to teach you a solo that is related to a square-root structure John and I have used in our work,” but he taught the dancers distinctive phrases that were generated, in part, using that structure. Rehearsal was not about where the movement came from, but about figuring out how it all worked in time and space.

When I make discoveries about the structure of a dance by studying Merce’s notes, I don’t regard those discoveries as more important or more authentic than what we learned from him in the studio. It’s more like looking at the same dance through a different lens. “Ah, yes, that makes sense, that’s what was going on.”

AM 52. Another compositional device Merce gave himself in Doubles connects to its title: he double-cast it, with two sets of seven dancers, and taught the five solos differently to each two dancers. How much was he himself teaching the solos differently, and how much was he enjoying the different ways in which each dancer interpreted the same instructions?

(And can you spell out for me which seven dancers shared roles with which other dancers in that original cast?)

PL 52. There were two solos for women, one made for Lise Friedman and Cathy Kerr, and the other for Louise Burns and Helen Barrow. There were three solos for men, one for Neil Greenberg and Chris Komar, one for Alan Good and Joseph Lennon, and a third one for Rob Remley and Robert Swinston. There was also a duet structured similarly to the solos that was done by Susan Quinn and Megan Walker in one cast, and Karen Radford and me in the other cast.

Merce took a novel approach to teaching Doubles. Rather than teach the solos to both casts at once, he brought dancers into the studio one by one. As a result, there are subtle (and not so subtle) differences in the how the solos were done by the two casts. For example, there’s a moment toward the beginning of the Cathy/Lise solo which is described in the notes as “step on R.” In the dance, Cathy steps forward on her right foot into a deep lunge, but Lise steps forward on her right foot into fourth position with both legs straight. The two moves look quite different, but they both correspond to the instructions “step on R.” What happened? When Merce demonstrated the movement, did his front leg look bent to Cathy but straight to Lise? Did he inadvertently or intentionally show the step differently? Did one of the women ask whether the right leg was bent or straight, and get the “correct” answer? Did they both ask and get two different answers? There’s no way to know, but the result of Merce working with the dancers one by one was that many such differences occurred. Very early in the process, it became clear to all of us that we were not meant to synch up the movement to make the two casts “match.” The differences were an integral part of Doubles.

Whether or not Merce intentionally generated those differences, it was inevitable that they would occur. This happened every day in class – Merce would demonstrate a phrase, we’d all learn and try to do the phrase, and because people saw things differently and danced differently, there would immediately be two or three versions. Someone might ask a question to clarify or iron out differences, but often a few variations would persist, and we would each do whatever seemed closest to what we thought Merce had shown or described. With Doubles, because the teaching was one-on-one, the differences cropped up and took root.

AM 55. In performance, this double-casting created a sensational effect within Cunningham devotees, as if appealing to the balletomanes within us, comparing Cast A to Cast B (and therefore making us look more closely at many dance details). Do you know of any earlier Cunningham work in which he double-cast a dance?

PL55. There were a number of dances over the years that were performed by two casts (in my time, for example, we had two casts for RainForest [9], Signals [10], and other early works), but of course that’s very different than having two casts from the start. There were also a few dances, like Canfield [11] and Changing Steps [12], in which some of the material was shared – as many as six pairs doing the same duet, for example.

But I think the first dance Merce double-cast from the start was Inlets 2, which premiered in 1983, the year before Doubles. This was a reconfiguration of an earlier dance called Inlets [13]. For Inlets 2, there were two casts of seven dancers. This was right before I joined the company, but I think the dancers learned it together. There were also many shared phrases, so lots of opportunity to cross-check material.

AM56. And do you know of any later work in which he did so?

PL56. Cargo X (1989) had two casts of seven dancers, but in that case Merce taught the dance first to one cast (the newer members of the company), and then those dancers taught their parts to the second cast. The double casting happened early, during the first week or so of rehearsal, perhaps before the dance was complete. I don’t quite recall. Touchbase (1993) was taught to three casts simultaneously – two casts from the Cunningham company plus one cast from Rambert Dance Company (a second cast of Rambert dancers learned it in London later). Rondo (1996) wasn’t double cast, but the casting was variable, with different dancers doing different segments on any given night.

Revivals were often double cast, especially in the later years when there were many more of them. That’s different than two casts to begin with, although the two casts of dancers would be encountering the material at the same time.

AM57. Merce had made many fabulous dances for individual dancers throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, but nonetheless experienced viewers of that era felt he was increasingly fascinated by ensemble. With Doubles, however, he showed the world just how fascinated he was by the individuals in his company, and how much he trusted his individual dancers to carry the particular beauties of his choreography.

With Pictures (1984), he had already created a work of immense beauty that was drawing audiences everywhere and casting a singular spell. Now with Doubles he was creating a different spell or several spells - its changes of tone and structures are part of its deeply human drama. Did it feel important that way at the time?

PL57. Doubles was my second dance, so I was too new to gauge how it fit into the arc of Merce’s work. It was momentous for me because I was at the beginning of my journey. But also, watching the dance unfold, I began to understand how deeply interested Merce was in the way different dancers saw, learned, and danced his movement. That was an important lesson early on.

The year after Doubles premiered, I inherited Lise’s part, which included the long solo that opened the dance. Cathy told me to learn Lise’s version, not hers, (very helpful advice), and also that it was “13s” (which helped me find the beginning and ending of at least some of the phrases). I studied the video of Lise diligently, but, because of the nature of the process, I didn’t replicate exactly what Lise did or how she did it. Over time, dancing that solo helped me feel increasingly confident and steady. With practice – and I practiced a lot – I learned to inhabit the solo and occupy the space.

AM 58. As you imply there, Merce then kept up the double-casting when individual dancers left. For a while, only Alan Good danced the role made for Joseph Lennon and himself, because of Lennon’s injury, but I remember Kevin Schroder dancing the Lennon version later in 1985. Was there any other work in which Merce maintained two versions of the same dance text?

Or perhaps I mean was there any other work in which Merce maintained two texts of the same dances?

PL 58. There was only one video made of the original two casts – a rehearsal video at Westbeth. Sadly, Joseph was injured when that video was made, so we only have a record of Alan’s version of the solo. Aside from anecdotal recollections, there’s no way to compare Joseph’s and Alan’s versions. I think Kevin learned the solo from Alan. When Louise Burns left, Helen danced in both casts for a while. Later, when Kristy Santimyer learned that part, I think she learned it from Helen rather than using video to reconstruct Louise’s version.

We maintained two casts for Inlets 2, Doubles, Cargo X, Touchbase [14] and some revivals. There were always variations in the way different dancers danced the same roles, but Doubles was the only dance in which those variations seemed integral to the dance.

AM 59. In its first year, Doubles became my all-time favourite Cunningham dance, and has tended to remain so over the decades. What’s more, it deeply impressed a number of more experienced viewers (among them Arlene Croce and Richard Alston) who felt it recaptured qualities they had loved in Summerspace and other early Cunningham masterpieces. It thrilled them when they saw it once, but then, more wonderful yet, they saw how it changed with Cast B. It stayed in repertory for several years.

Merce then returned to it in the final year or two of his life, working on a chamber Doubles Suite with the RUGs (Repertory Understudy Group) who became an increasingly important part of his work towards the end. I understand that he loved rediscovering Doubles.

Having shown people (those who chose to notice, anyway!) how much he trusted his 1984 dancers, and having shown his dancers how valued they were with this work, Merce then made Native Green (1985), one of his now relatively rare chamber works (and a very successful one), with just six dancers (and only one cast). We’ll come back to that, but from then on Merce and his company seemed in marvelous accord for the rest of the decade. Few dancers left, most dancers stayed for long periods, the company reached and sustained new peaks of popularity, giving in some years more performances than ever before. One of the many peaks of this era came with August Pace (1989), when Merce made no fewer than seven duets (fourteen dancers), allowing each couple - and each dancer within each couple – to register very powerfully and vividly, and even making a special role for the fifteenth. In 2019, you reconstructed August Pace and brought back thirteen of that cast of fifteen to help. Again, we’ll return to that in greater detail later, but my point is that these years, 1984-1989, showed Cunningham’s deep excitement with - and trust in - the dancers of that era. What would you like to say about this?

PL 59. The 1980s were a very busy time for the company. We toured and performed a lot and rehearsed even more. Merce was making on average three new dances a year as well as working on film projects. He taught company class three times a week in New York, and more often on tour. There were always dancers leaving and new dancers arriving, but there was a sense of stability, of knowing this group and how it operated. We spent a lot of time together and covered a lot of ground.

AM 60. These works weren’t radical or subversive dance theatre in the way that Winterbranch (1964) or Variations V (1965) or Canfield (1969) were, but it showed Cunningham deeply and intimately in love with dance itself and with the dancers of the moment.

Meanwhile there was plenty of craziness in several other creations of those years, as we remember in Grange Eve (1986), Carousal (1987), and Cargo X (1989). The fact that Merce himself was dancing in every programme, in his sixties and even seventy, until November 1989, was one source of perpetual controversy for audiences; the scores by Kosugi and Tudor and others were another source of controversy. This wasn’t neatly pretty dance theatre! We’ll have more to say of this, but how would you describe Merce’s main creative lines of thought in the years 1984-1989?

PL 60. What I remember most is how Merce pushed us to be bigger, faster, stronger and more expansive. There was a rhythmic urgency pulsing through the work, an athleticism. Not every dance landed, but there were some magnificent works that were magnificent to do. With August Pace, Merce began a several-year experiment with off-balance – which, after years of building the strength and composure to be on balance, was especially thrilling.

AM61. I would say that Merce’s notes give us many amazing insights into how he composed and prepared a work. But are they ever of practical use in reviving a work? And why did he ask a few trusted stagers to use them when reviving works?

PL61. All the time! Merce’s notes are extraordinarily helpful, especially when used side-by-side with video. Often Merce used one notebook to record the structure and continuity of the dance, and another notebook to record the gamut of phrases that make up the dance. The notes about the phrases are probably the more practical source of information. In those notes, Merce recorded each of the phrases using a combination of numbers, words, stick figures and directional arrows. His notes can be cryptic, and it takes time to learn to decode them. But when viewed alongside video, the notes illuminate the video, and the video illuminates the notes. I can reconstruct a dance using video alone, but it involves more guesswork. Using the notes and video in tandem makes for a slower and more tedious process, but it’s worth the effort. And along the way there are unanticipated discoveries and rewards.

AM 62. Lincoln Kirstein liked to accuse “the modern dance” of being a cult of idiosyncrasy, an array of personal techniques and personal styles based on the idioms that physically suited individual dancer-choreographers, whereas ballet, he argued, was wonderfully impersonal, based on an old technique that transcended either personality or idiosyncrasy. In general, I feel that the Cunningham technique and style is based on neither personality nor idiosyncrasy, even if (as in ballet) individual roles may remain connected to individual dancers. Doubles is a case in point: it may celebrate its original casts at some level, but it’s not about Merce’s idiosyncrasies or his personality.

Do you agree? Or rather, can you say where you agree and where you disagree? and why?

PL 62. When I arrived at Westbeth in 1982, there was an established technique and a full schedule of classes. The teaching wasn’t pinned down or pedantic, and there were a variety of teachers, but the classes had a clear structure and arecognizable vocabulary, and for the most part prioritized big, clear, dynamic, dancing. The technique, and the teachers of the technique (Merce in particular), trained us to see the movement and to approach the movement in a similar way. Similar, but not exactly the same. We all brought our own perceptions, proclivities, and abilities to the task. We all managed to realize the movement, to physicalize the instructions, in our own way with our own bodies. Because we were each different, we each did the movement differently. That was something Merce expected. As long as those differences emerged from an authentic effort to embody the movement fully, he didn’t just tolerate the differences, he valued and even encouraged them.

AM 63. In ballet, I’ve seen a few roles danced by their originators that, amazingly, looked even better with certain subsequent interpreters. Have you ever felt this with Cunningham dancers or post-Cunningham dancers?

PL 63. I try avoid the word “better.” I try to think in terms of “different in a satisfying and authentic way.” The more time I spend teaching Merce’s work, the more interested I become in how the work behaves when inhabited by different dancers. I could loop back in time and highlight marvelous performances by many marvelous dancers, both former company dancers and dancers who never met Merce. Right now, though, what jumps to the forefront of my mind is a very recent and extraordinary performance of Merce’s solo from Exchange done by Clarricia Golden, a member of Philadanco, as part of an Event at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Joseph Lennon came to see the show, and afterward wrote to me: “The solo confirmed everything I’ve been feeling about seeing the work these past couple of years. I’ve stopped looking for my idea of what it was and just open myself to the beauty of the present. Who knew that a young, small, woman could inhabit so thoroughly a solo Merce made when he was 59?”

AM 64. Have you looked at the notes for Phrases (1984)? I found them visually fascinating.

PL 64. I never have. You’ve made me curious.

AM 65. What do you remember of Phrases? It seemed a toughly rigorous piece for both dancers and audience, but it was in its way meaty.

PL 65. Most of what I remember about Phrases is anecdotal. Phrases was made during a prolonged residency in Angers, France during my second year in the company. We were housed in an old school dormitory – it felt a little like camp. I was in heaven – practicing my French, taking Merce’s daily class, learning new and old repertory. I think many of the senior company members found the long residency in a provincial town excruciating.

I remember very little about the dance, except that we would often begin rehearsal by doing “the phrases” together as a group. And then that became the title: Phrases. Because it was France, there were open rehearsals and other public events in advance of the premiere. I began to understand the degree to which the French regarded Merce as a celebrity. I was costumed [15] in a bright yellow unitard, and at various times I was supposed to add a black waistband, or black leg warmers, or a black choker. Someone dubbed me “Mary Tyler Banana.” The dance didn’t last long in the repertory, and I’ve never watched a video.

AM 66. You hadn’t been in the Cunningham company long when he put you in the original cast of Native Green (1985), an intimate sextet.

To me, this work was

(a) one of his anthropological fantasies, an idea of a joyous ritual in I know not which part of the world ;

(b) an exercise in his version of release technique, the rippling connective method that Trisha Brown had been making wonderful [16];

(c) a wry reflection on his own age (“native green” is a phrase from the final poem by Nonno, The World’s Oldest Active Poet, in Tennessee Williams’s play The Night of the Iguana);

(d) dedicated to Edwin Denby, another Nonno, who had died in 1983, a friend of Merce’s and Cage’s from 1943 or earlier.

Can you say what this piece was like for you?

PL 66. I’ve never heard any speculation about the source of the title. It seemed an odd one, unlike Merce’s other titles. I find it interesting that it may have come from a poem.

That aside, for me Native Green was all about Megan Walker. She was a marvelous and eccentric mover, and I think Merce enjoyed her both as a person and as a dancer. She sparkled. I have no evidence for this, but my sense at the time was that he studied her way of moving, analysed it so to speak, and turned it into a kind of system in which the head, torso, arms and legs all moved independently. I know now, from seeing his notes, that he worked out the coordination of the different body parts using chance operations. He spent a considerable amount of time working with Megan on her opening solo, and then brought Helen and me into the studio to discover what Megan was doing, and to figure out a way to do it ourselves. Again, I have no evidence for this, other than the odd feeling I had at the time that doing the movement made me feel like Megan. Native Green was a profoundly personal dance for her, a great gift from a great master. Helen was already an accomplished and refined dancer, and soon found her own elegant way into the material.

I was greener than green, and everything about the dance was unlike how I moved. In other words, it was an invaluable opportunity. I realize I haven’t mentioned the men…

AM 67. Merce, curiously, dedicated not one piece to the memory of Edwin Denby but two. The other was Grange Eve (1986). Did you ever hear Merce speak of Denby? (To me he did.)

PL 67. Sadly, no. I have read some of his writing, and I know Merce admired him.

AM 68. Native Green was from the Bill Anastasi era, by no means his worst designs. Nonetheless nobody has much love for Anastasi’s or Dove Bradshaw’s work for Cunningham dance theatre. (Anastasi and Bradshaw were painter friends of John Cage whom Cunningham often invited to design sets and costumes between 1985 and 1991.)

Any comments?

PL 68. I’ve recently listened to an excerpt from Elliot Caplan’s Cage/Cunningham documentary (1991) in which Jasper Johns talks about his approach to being the artistic advisor for the company: “Having a sense of what [Merce] is about, I’ve always had the feeling that I would try to work to not interfere with that expression and to leave it free of any kind of thing of mine that it had to carry. So most often I’ve done very little.” Bill Anastasi and Dove Bradshaw took a different approach – they gravitated toward intricately painted backdrops and costumes with multiple bits and pieces.

AM 69. Native Green also introduced the composer John King to the Cunningham enterprise. Any comments?

PL 69. John King is a terrific composer and a warm, generous person. The two compositions he made for Merce during my time in the company were both homeruns – gliss in sighs (for Native Green) and blues99 (for CRWDSPCR). To me, both had an edginess that invigorated the dances, very present andstrong, and yet not overwhelming. These days, I often consult John for his advice and expertise about the music side of ourlicensing projects. He has also composed and performed works for many of our Event projects, most recently in collaboration with Leyya Mona Tawil at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

AM 70. I wish I remembered Arcade (1985) better: it had real beauties. (And I have a fabulous poster of it advertising MCDC’s 1987 Sadler’s Wells season.) I know that it was commissioned by Pennsylvania Ballet: Merce made it on his own dancers but then taught it to the Pennsylvania dancers, who gave its premiere in 1985. Shortly after, it entered Cunningham repertory, staying for more than a year. Your memories?

PL 70. I don’t remember Arcade well either. It was one of those dances that seemed to be one thing in the studio, and something altogether different on stage.

Recently, on a visit to University of the Arts, I discovered that most of the ballet faculty had been in Pennsylvania Ballet’s production of Arcade.

AM 71. Your memories of Grange Eve?

PL 71. Grange Eve was one of Merce’s comedies – what you’ve quoted Ellen Cornfield as calling “the funnies.” As the title suggests, it referenced the kind of social dancing that might have been done in a grange hall, as well as the goings-on along the side lines (a fight, drunken weaving, etc). Not a ground-breaking dance – it was used as a program closer. My favorite bits were the very beginning when we entered one by one doing variations on two or three different walking phrases. And, later on, the “cane dance” for Merce and the other men. Each man had a different score, determined by chance, that specified when to step right, when to step left, and when to “step” with the cane. Using those shifts of weight (right, left, cane), the men made up their own phrases. I borrowed one of those canes during my recovery from foot surgery.

AM 72. Fabrications (1987) is a piece in which you danced and which you, with ideal results, later resurrected, during Merce’s final years. Do you regard this as one of Merce’s dramas? How would you characterise his own role and its relation to the rest of the work?

PL 72. Fabrications was a lush, grand, expansive dance. The phrases were classic examples of movement from that time period – big steps, long lines, deep torso work, and lots of triplets and jumps. Very satisfying to do.

Structurally, the dance is an arrangement of groups (solos, duets, trios, quartets, quintets, sextets) that occur in pairs (a duet with a quartet, a sextet with a trio, etc.). So there were lots of entrances and exits, assembling and dispersing, dancing with a new partner or a new group. There was no story or through line, but there was definitely a sense of momentum and connection which could read as drama.

Years later, when I was studying Merce’s notes, I found a sentence at the bottom of one page that read: “Whenever possible, physically join the dancers [use an increasing physical joining as dance continues].” And I thought, “Yes, that is what happened.”

Merce himself made multiple entrances in the dance – sometimes dancing alone, but often inserting himself into a group or dancing with a partner. There was a large age gap between Merce and his dancers, so even when he was part of a group doing the same or roughly the same movement, he was still “other.” But to me he seemed part of the community. He was dancing with us.

AM 73. You now know, from studying the notes, that meanings were sometimes there in his planning of a work. For example, the Indian permanent emotions in Fabrications.

But it’s also very possible that in these cases (unlike “Shards”) meanings were just a compositional stimulus, and he didn’t mind if the work grew into a quite different animal. Fabrications does not seem to be “about” the permanent emotions, even if it somehow contains them. It’s a great work, but for different and larger reasons. Do you agree that Merce often just used meanings as an ignition key, something to get him started on a piece?

PL 73. I think your term “ignition key” is valid, although I don’t think it was just at the beginning to get things started.

I think Merce drew inspiration from multiple sources – the natural world, urban life, art, science, technology, movies – and those experiences and images informed his dance-making in powerful and playful ways. I’d go so far as to say “inhabited” his dances in magical ways. But I don’t believe he was trying to use his dances to convey those ideas or images to the audience. He wasn’t storytelling, or trying to get the audience to see what he had seen. He was dance-making, and asking the audience to look at the dance he had made – look at this, see what you see, make up your own mind. For Merce, I think, it wasn’t about where the dance came from, but where it got to.

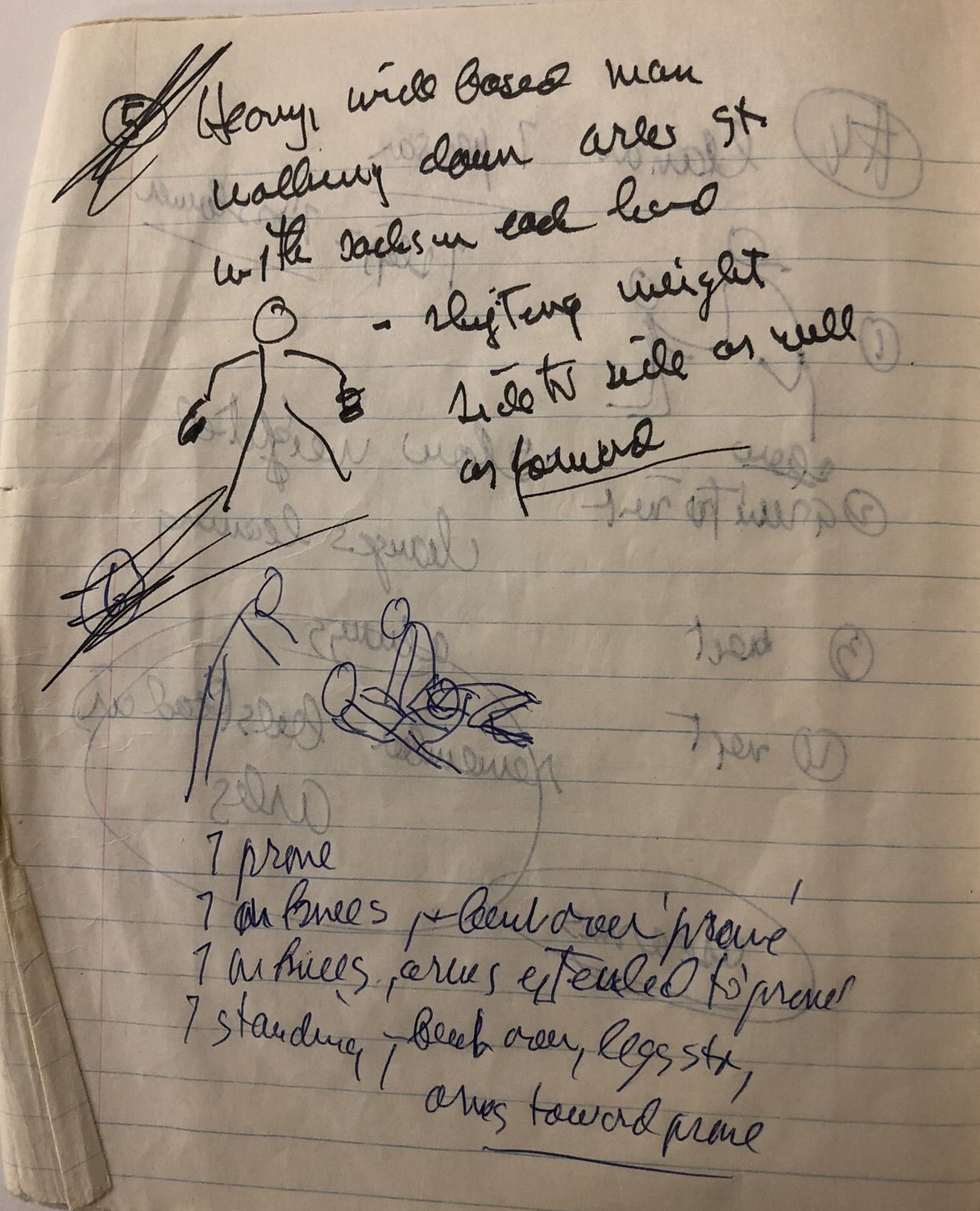

In Merce’s notes for August Pace, there’s a rough sketch of a stick figure holding two bags with a caption that reads “Heavy, wide based man walking down Arles street with sacks in each hand – shifting weight side to side as well as forward.” <See illustration 9. AM> Merce saw that and thought he could use it. But I’m quite sure he didn’t expect the viewer (or for that matter the dancer) to think, “Ah, this must have to do with a heavy French man burdened with sacks.”

Notes

1.Charles Atlas (b.1949) was assistant stage manager to the Cunningham company from the early 1970s to 1978, during which time he began to collaborate on film/video projects with Cunningham. In 1978-1983, he was the company’s filmmaker in residence, making ten dance films.

2.Elliott Caplan joined the Cunningham enterprise as Atlas’s assistant in 1977. In 1984, he succeeded Atlas as filmmaker-in-residence, remaining until the mid-1990s.

3. Points in Space was choreographed for camera in 1986, first shown in its screen version in November that year, and first presented as a stage dance in March 1987.

4.Changing Steps was made in 1975 as a stage dance. It was chiefly used as a source of material – adapted in many ways - for Events. The video version was made in October 1988 and first screened in May 1989.

5.The stage work Beach Birds had its premiere in June 1991. Beach Birds for Camera was filmed in December 1991.

6.Locale was recorded as a Filmdance in January-February 1979. The stage version had its premiere in October 1979. The filmdance was first screened in February 1980.

7.Channels/Inserts was recorded as a Filmdance in January 1981. The stage dance was first performed in March 1981. The filmdance was first screened in March 1982.

8.Coast Zone was made as a film dance in January 1983, first staged in performance in March 1983, and first screened in public in April 1984. Lent became a RUG (Repertory Understudy Group dancer) in 1983 and a company member in 1984.

9.RainForest (1968), a work for six dancers (one of them originally Cunningham), was first revived in Lent’s day in 1988, for the first time in a dozen or more years. After that, it was revived fairly regularly until 2011.

10.Signals (1970) was also for six dancers, one of them originally Cunningham.

11.Canfield (1969) featured nine dancers, including Cunningham. Much of its material was subsequently used in Events.

12. Changing Steps (1972) originally featured ten dancers: Cunningham was not one. “To be performed in any order, in any space, and in any combination,” it varied in length from twelve and forty-eight minutes. Parts of it were frequently employed in Events material.

13.Inlets (1977), a work for Cunningham and five other dancers with a memorable set designed by the painter Morris Graves, remained in repertory until 1981.

14.Touchbase (1992) was commissioned by the British modern dance company Rambert Dance Company. Cunningham created it for three casts: seven Rambert dancers, who performed its premiere in the United Kingdom, and two teams of seven Cunningham dancers, who began performing it in 1993.

15.Costumes for Phrases were by Dove Bradshaw.

16. It should be emphasized that, although many felt Trisha Brown’s work exemplified release technique, she herself did not use the term. “Release technique” had already been developed in the 1960s by Joan Skinner (1924-2021), who (as it happens) had danced in new creations by Cunningham in 1951-1952. Skinner, who danced in the Martha Graham company, remained friends with Cunningham in later years; she moved to Seattle in 1967, remaining there until her death.

1: Patricia Lent accepting a Bessie Award on line on behalf of the Merce Cunningham Trust after its 2019 “Night of a Hundred Solos”.

2: Patricia Lent demonstrating Cunningham technique in this century.

3: Patricia Lent.

4: Alan Good and Patricia Lent in 2019 demonstrating a sequence in the August Pace duet they had created in 1989.

5: Alan Good and Patricia Lent in 2019 demonstrating a sequence in the August Pace duet they had created in 1989.

6: Patricia Lent working with the cast of 2019 (Logan Pedom and Callejah Smiley) on the duet she and Alan Good had created in 1989 in August Pace.

7: Patricia Lent working with the dancers of 2019 (Logan Pedon and Callejah Smiley) on the duet she and Alan Good had created in 1989 in Cunningham’s August Pace.

8: Patricia Lent in 2019, thirty-five years after joining the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, demonstrating a movement to two of the male dancers in the revival of August Pace (1989).

9. As Patricia Lent discussed at the end of this interview, Merce Cunningham’s notes for August Pace (1989) include this drawing of a man he had seen in an Arles street weighed down by heavy shopping bags. Cunningham was looking for a weighted quality in his choreography for August Pace.