The return of “The Sleeping Beauty” to Covent Garden

Prince Harry’s view that the royal family is all about public relations is scarcely new. Elizabeth I of England and Louis XIV of France were masters of propaganda, who connected the court and the arts and the whole structure of national civilisation. The ballet of “The Sleeping Beauty” - first presented in St Petersburg in 1890 (music by Tchaikovsky, choreography by Marius Petipa) and revived on Monday 16 by the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden in the 2006 production staged by Monica Mason and Christopher Newton - is all about the survival of a royal family. It actually makes us care about those royals by making us feel they’re central to civilisation, to chivalry, to social and artistic harmony, to formal beauty at its most fragile but luminous.

Any healthy sceptic ought to be outraged by the way the ballet links royalty to divinity - a flock of fairy godmothers arrive at the christening to the heir to the realm, the most welcome but not the most surprising of guests - but no: it proves as easy to accept this myth as it is to accept the connection of gods to humans in Homer. By dancing the language of ballet, the fairy godmothers embody the classical principles that irradiate this court. When baby Aurora grows up, she resembles her divine godmothers even more than her more pedestrian parents.

Yet the old ballet slumbers or wakes according to how innumerable points of style are realised. On Monday, when the fairy ensemble spread across the stage in a series of ballet phrases and tableaux, I remembered how these moments, in the last century at Covent Garden, often seemed the quintessence of civilised beauty, and I noticed the tiny failures that now make them seem merely pretty routine. When the six fairy godmothers are all supported in sculptural attitude (one raised leg ideally angled), they used to hold precisely the same angle whereas now they show a range of approximations. When they all stand in three-dimensional fullness and slowly raise, then part, their arms (a unison port de bras), the gesture is now bland where it, especially the parting of the arms, used to be dynamically charged. The six solo variations, each so singular, still show a wide range of dynamics, and yet, on Monday, too narrow. The dynamics don’t now quite have the internal contrasts that used to catch the breath. And individual fairy godmothers seem more concerned with inoffensive correctness rather than with individual imagination.

Fortunately, Monday’s fairies were the production’s dullest ingredient, along with the king and queen, who were all too Madame Tussauds. As the court’s weak fusspot chamberlain Cattalabutte, Thomas Whitehead showed a fabulous flair for characterisation that kept telling the old story as if for the first time. When Kristin McNally entered as the vindictive Fairy Carabosse, she, too, made details matter. The keen malice with which she plucked his hair from his scalp was both funny and disturbing. Then, as the Prologue ended with harmony restored, the accumulation of the final, tiered, diagonal dance tableau across the stage once again showed the old Royal Ballet singing exemplification of classical style.

Marianela Nuñez, Monday’s Aurora, showed that classical style to a very high degree but only intermittently showed the command of dynamic contrasts that would turn style into drama. When coaching Aurora’s supported pirouettes in 1946, Frederick Ashton would say “it’s like you’ve been shot in the back!” when explaining how those pirouettes should suddenly end up with firm positions. With Nuñez, both pirouettes and arrival were of the same even consistency. She had two glorious moments in Act One: little, hovering jumps in Aurora’s entrance dance, and lingeringly off-balance (renversé) turns in her last entrance. Even so, Act One’s liveliest and most heart-catching dance belonged not to her but to her eight female companions.

Like too many interpreters of Aurora, Nuñez used not to shape this three-act role in an arc. Now, however, she does. When Aurora becomes a vision in Act Two, she was far more poetically expressive than in Act One, remote and yet visibly longing. In the Act Three wedding, she danced with an authoritative dignity that had real poignancy, though coloured her and there by playfulness and exultance. Hers was a measured, seldom exciting, but generally admirable performance. Much the same was true for her Prince, Vadim Muntagirov, marvellously stylish, not always expressively assertive.

The production has not significantly changed for over ten years. In several details - notably that diagonal at the end of the Prologue and the solo variation for the vision of Aurora in Act Two - it actually improves upon Petipa’s 1890 original. I wish, however, that the Arrival of the Palace were well staged (Carabosse is clumsily featured where the music tells us she is a mere memory), and that the transition into Act Three were presented with curtain up, as used to happen in 1946-1967.

Though there is some sour brass playing, conductor Koen Kessels has begun to shake off some of the indulgently too-slow tempi that marred several pre-pandemic revivals of this production. Several supporting performances on Monday had more detail than in early 2020. The Vision Scene nymphs danced with far more romantically telling phrasing than I have seen for years; Claire Calvert, in the divertissement for Florestan and his two sisters, showed everyone how to use music to maximum effect. In the many jumps for the Bluebird, Joseph Sissens was a fount of avian energy. Whereas the Prologue had left me feeling this would be my only “Sleeping Beauty” this season, Acts Two and Three made me want to return several times. Cast changes, tedious when a production has lost its edge, now look enticing.

Originally published in “Slipped Disc” in January 2023

@Alastair Macaulay 2023

1: Kristin McNally as Carabosse in “The Sleeping Beauty” at Covent Garden.

2: Marianela Nuñez as Princess Aurora in the opening sequence of the Rose Adagio in “The Sleeping Beauty”.

3: Marianela Nuñez as Princess Aurora in preparation for the first balances in the Rose Adagio in “The Sleeping Beauty”.

4: Marianela Nuñez as Princess Aurora in the first attitude of the Rose Adagio in “The Sleeping Beauty”.

5, 6: Marianela Nuñez as Princess Aurora regarding the first roses presented to her in the Rose Adagio in “The Sleeping Beauty”.

7: Claire Calvert as one of Florestan’s two sisters, dancing Petipa’s Diamond variation amid Frederick Ashton’s Florestan pas de trois, at the Act Three wedding in “The Sleeping Beauty”.

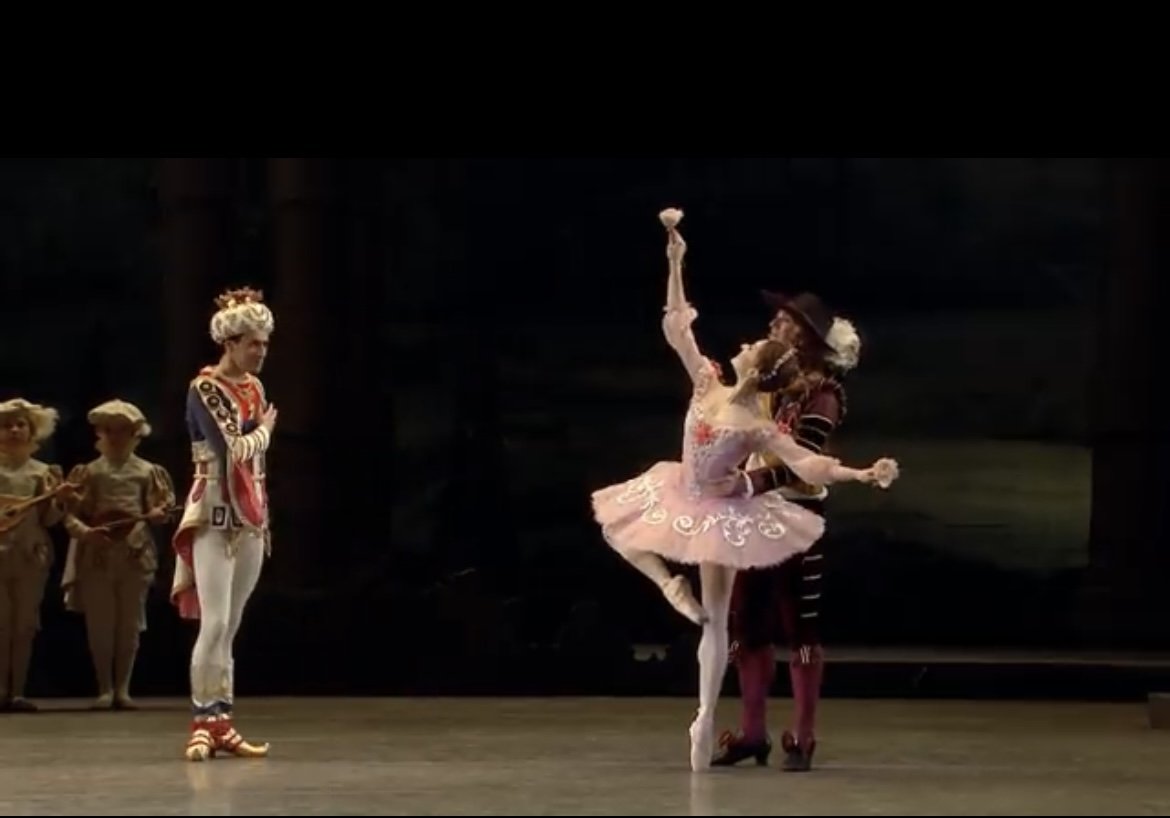

8: Marianela Nuñez (Princess Aurora) and Vadim Muntagirov (Prince Désiré) in the concluding image of the Act Three wedding pas de deux in “The Sleeping Beauty”.