The programme for an October 1936 Sadler’s Wells “Swan Lake”

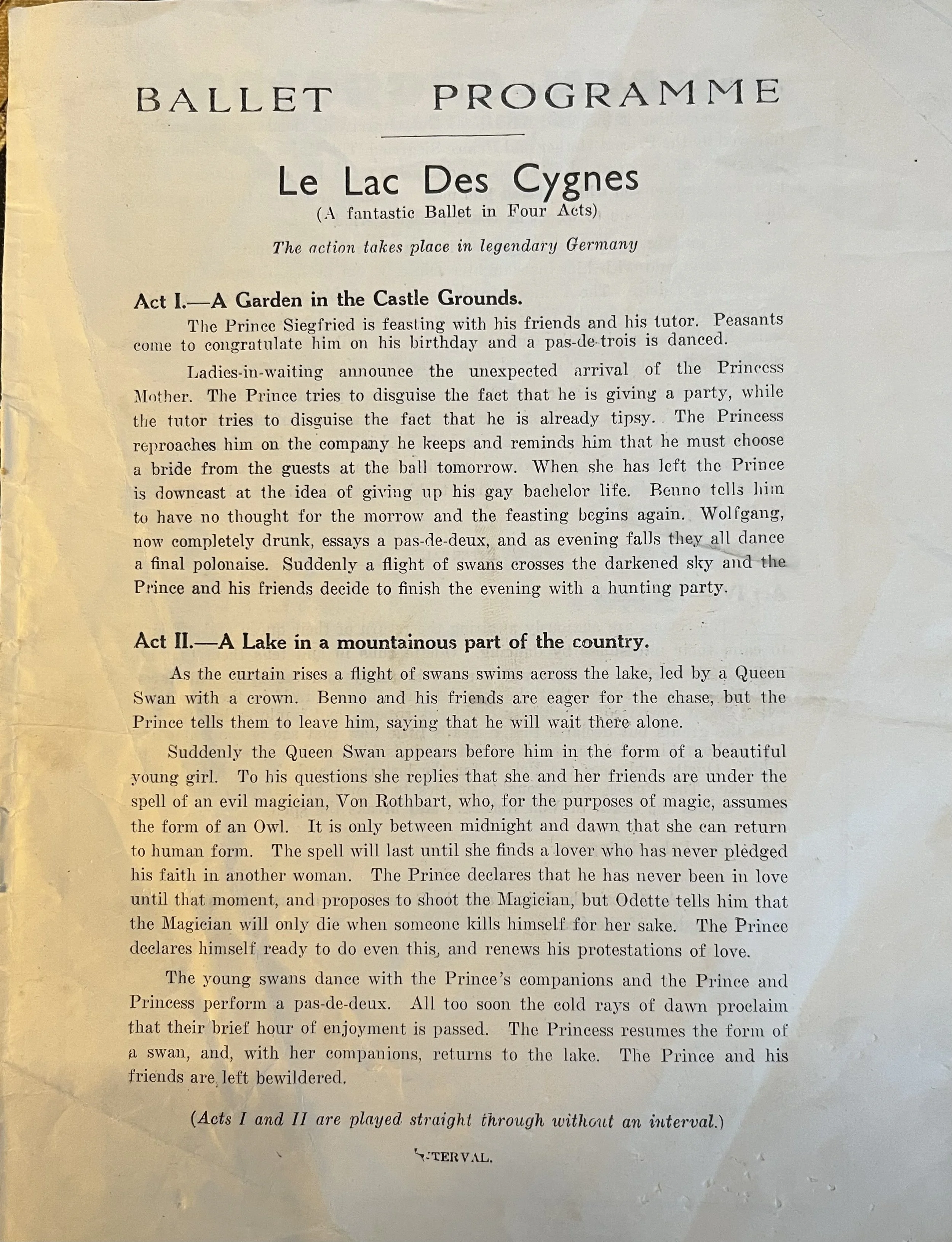

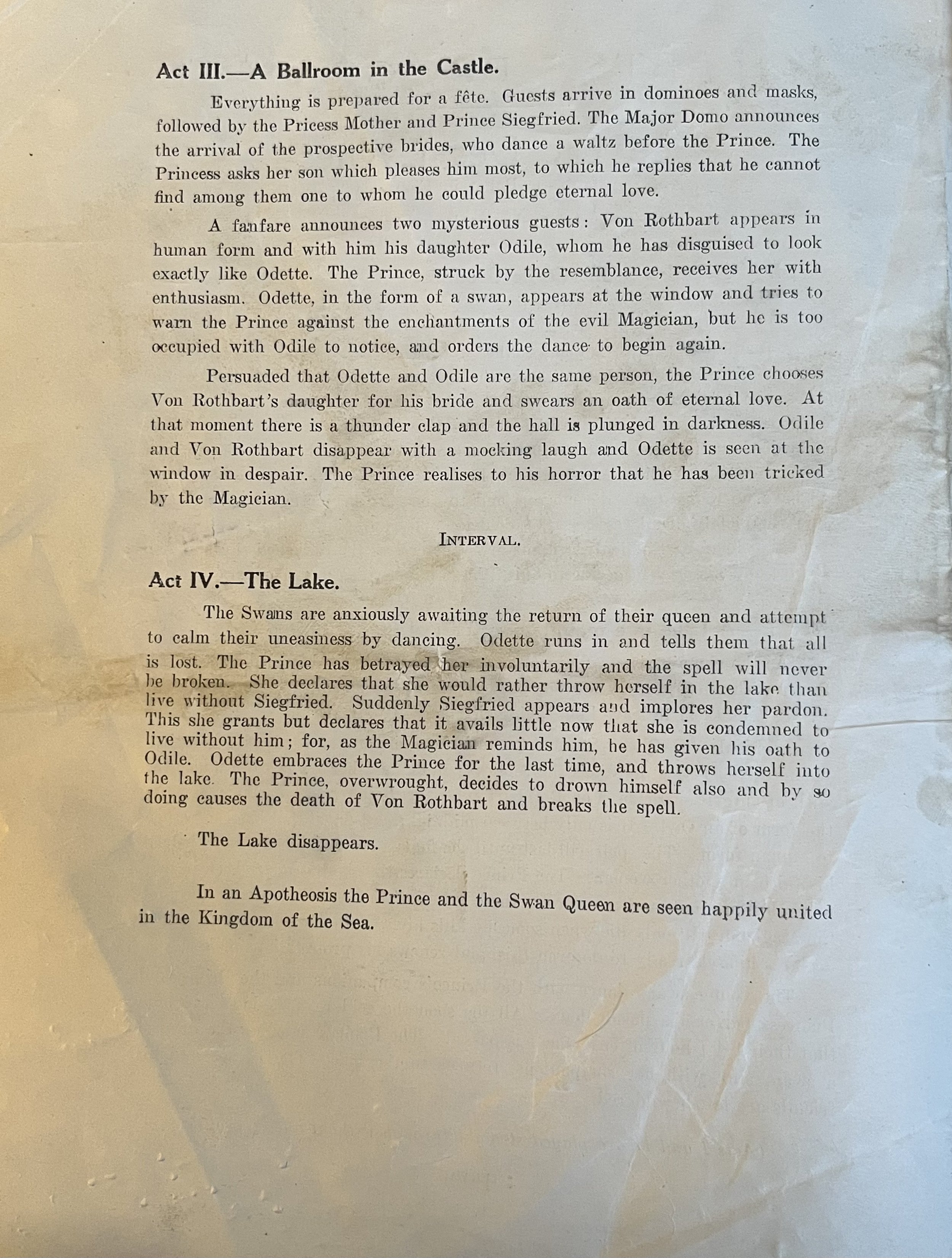

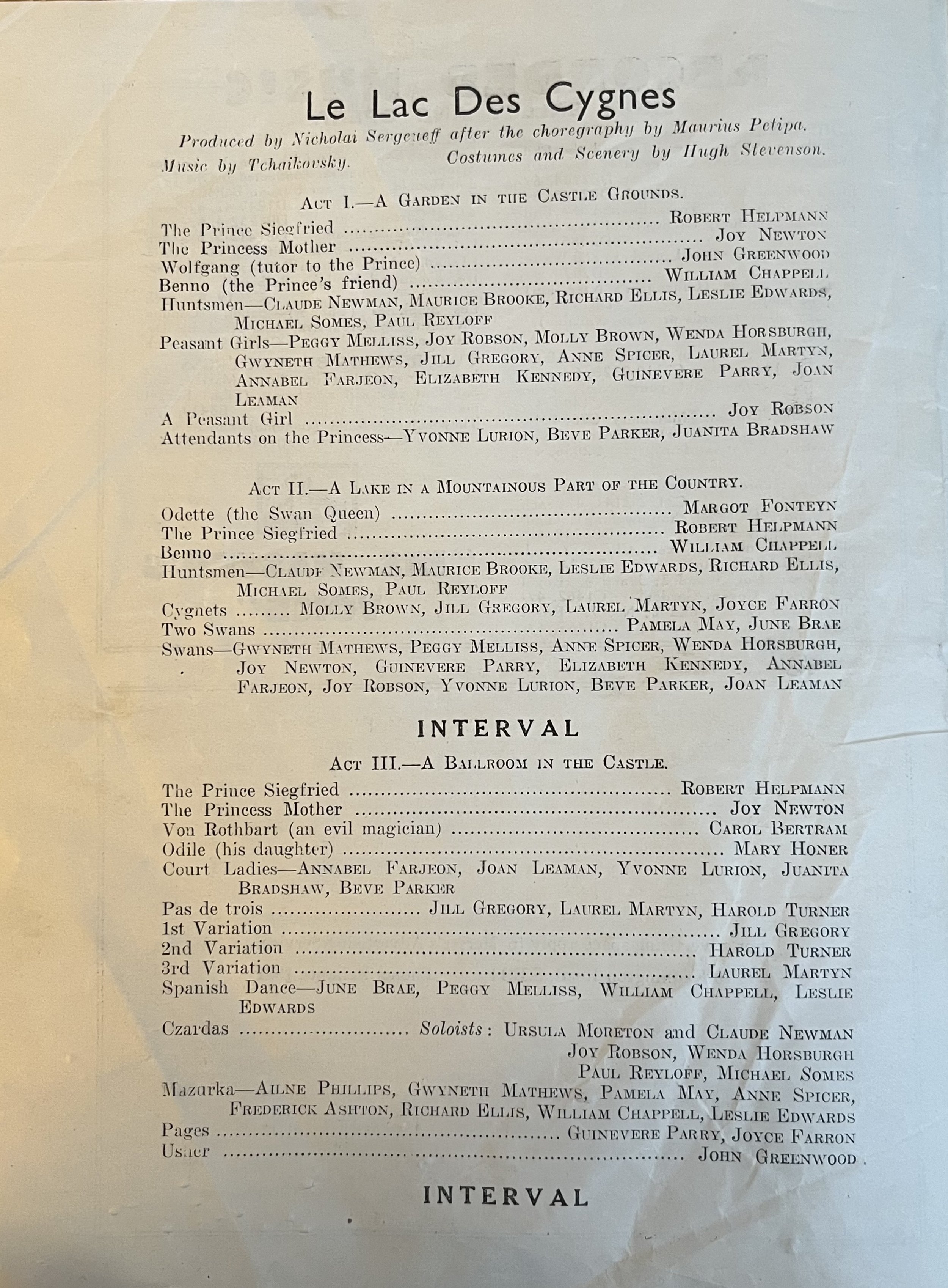

This Sadler’s Wells programme for a Vic-Wells Saturday matinee of “Le Lac des Cygnes” (“Swan Lake”) on October 24, 1936, is packed with interest. For example, the scenario announces that the pas de trois is danced in Act One; but the cast list on page 5 shows that the pas de trois (not danced by Benno, as in so many misguided productions today) actually is to be danced in Act Three (the ballroom), where it doesn’t belong. (More oddly yet, the Royal Ballet went on sometimes dancing the pas de trois in later years. When Frederick Ashton added his gloriously sophisticated pas de quatre in 1963, to music entirely from the Act Three ballroom, he made the error of inserting it into Act One, where it remained until early 1972.)

Good news is that the Princess Mother doesn’t give her son a crossbow - that mistake only began in the 1960s. Interestingly, no Waltz is danced in Act One: the Royal Ballet lacked the personnel in the 1930s to dance Marius Petipa’s original waltz (which was never seen jn the West until 2016 - thank you, Alexei Ratmansky and Zürich Ballet); Frederick Ashton did not choreograph the first version of his “Swan Lake” waltz (a pas de six) until 1952 (his second version, a pas de douze joined by Prince Siegfried, was choreographed in 1963). The scenario makes it admirably clear that Odette, as seen by the lakeside, is a woman (not a swan, as many silly people still think); remarkably, Odette also tells Siegfried (was this mimed?) that Von Rothbart cannot die until someone kills himself for Odette’s sake. A further point of interest is that the lake disappears at the ballet’s end.

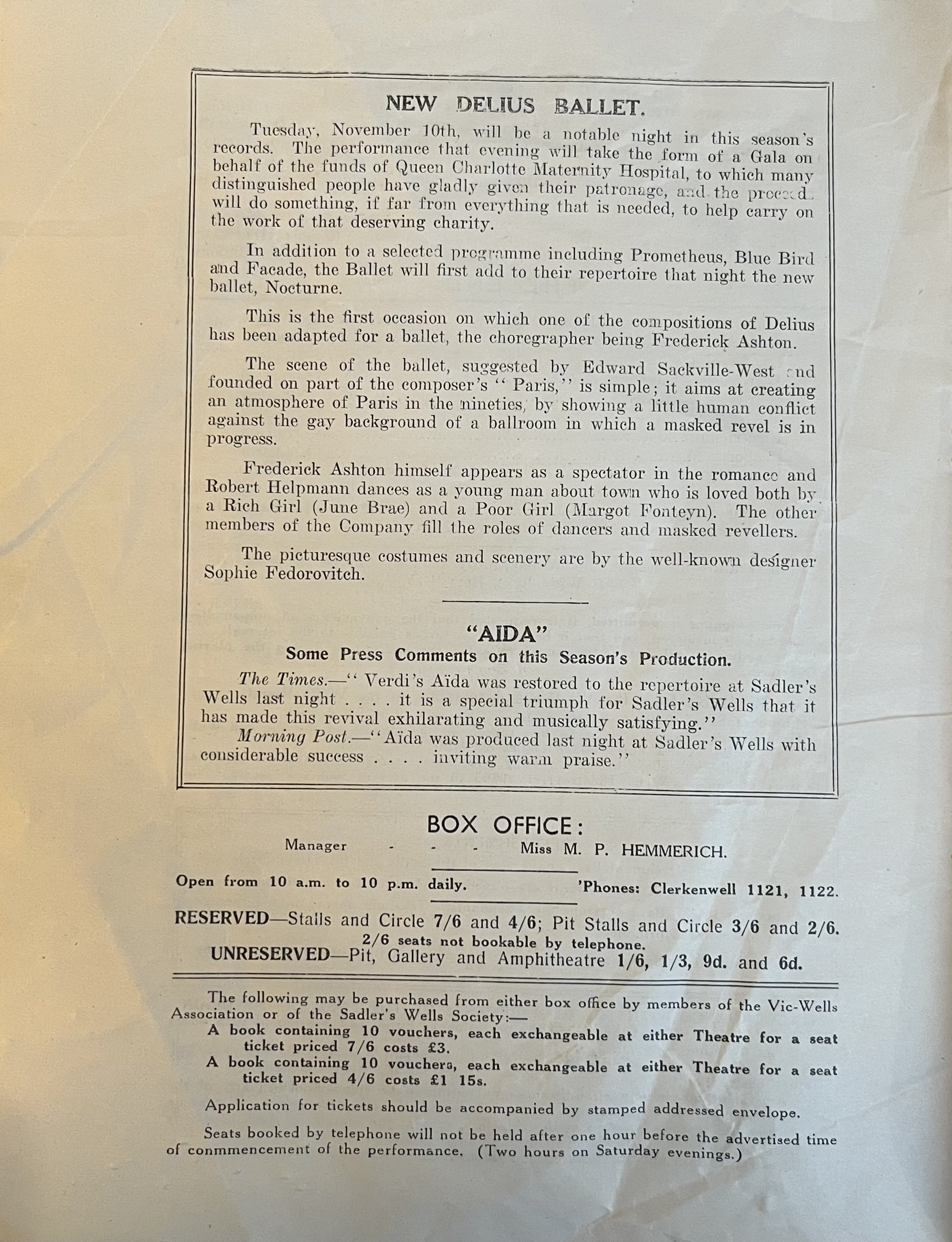

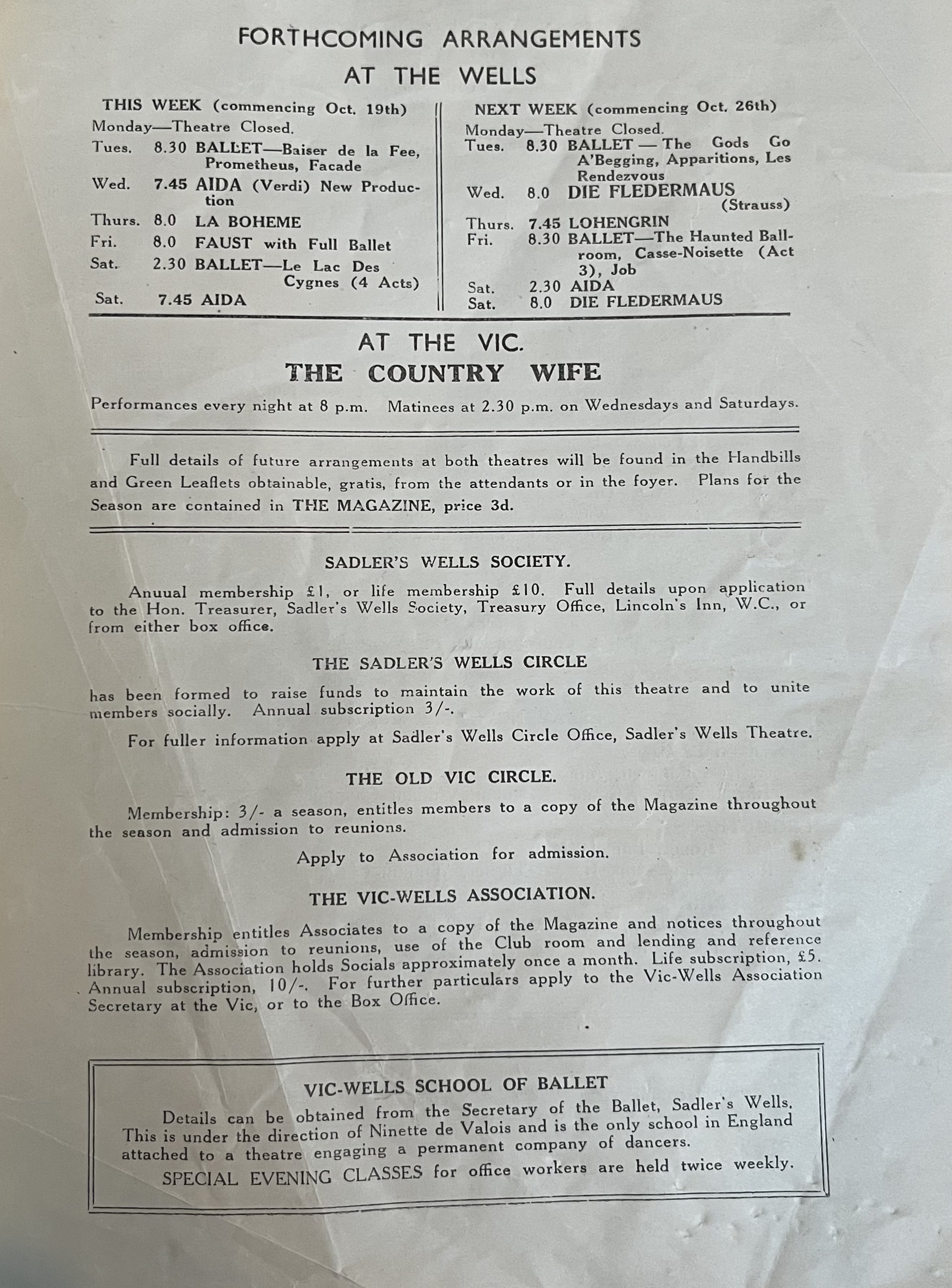

The programme has other revelations, too, such as the announcement of Ashton’s forthcoming Delius ballet, “Nocturne” (1936). It’s worth noting that, though Sadler’s Wells then operated on a very low budget, it managed to present three different operas and two separate ballet programmes in the course of each week.

But it’s the casting on pages 4-5 that fascinates most. Margot Fonteyn (1919-1991), aged sixteen and a half, here dances Odette but not yet Odile. Odile is danced instead by Mary Honer (1913-1965), a strong technician of a comedy-soubrette type: in the next year, she would create one of the virtuoso “Blue Girls” in Ashton’s “Les Patineurs” (the fouetté one) and the Bride in his “A Wedding Bouquet”. (Fonteyn later danced Odile from her late teens up until the age of fifty-three.)

Jill Gregory (1917-2010, later the longerm ballet mistress of the Royal Ballet until the 1980s) and Laurel Martyn (1916-2013, an Australian who returned to Australia in 1938, dancing with the Borovansky Ballet) dance in all four acts, even though their roles include the Act Two cygnets and the aforesaid Act Three pas de trois. Ashton himself is dancing in the Mazurka. Although William Chappell (1907-1994) had already established a reputation as a designer, here he is not only Benno, the prince’s friend in Acts One and Two, he’s also in the Act Three mazurka. Leslie Edwards (1916-2001) - who was soon to spend decades alternating between the role of Benno (he was nicknamed “Leslie Edwards, the prince’s friend”) and the Lord Chamberlain or Master of Ceremonies in Act Three - is a huntsman and then another Mazurka dancer. Michael Somes (1917-1994), who has recently had his nineteenth birthday, is a huntsman and in the czardas. Pamela May (1917-2005), later to become an Odette of note herself as well as a frequent dancer of the pas de trois, dances one of the Two Swans in both Acts Two and Four, while in Act Three joining Ashton, Chappell, Edwards, and the others in the Mazurka.

And the fourteen-year-old Joyce Farron already has the puff to dance one of the four Act Two cygnets and one of the four Act Four black cygnets, while spending Act Three onstage as a page. She was soon to be renamed Julia Farron (1922-2019), creating roles for Ashton, de Valois, John Cranko, and Kenneth MacMillan, and becoming a beloved teacher at both Royal Ballet School and Royal Academy of Dancing. Like Fonteyn, Gregory, May, Edwards, Somes, and others, she was to be part of the fabric of British ballet for decades henceforth.

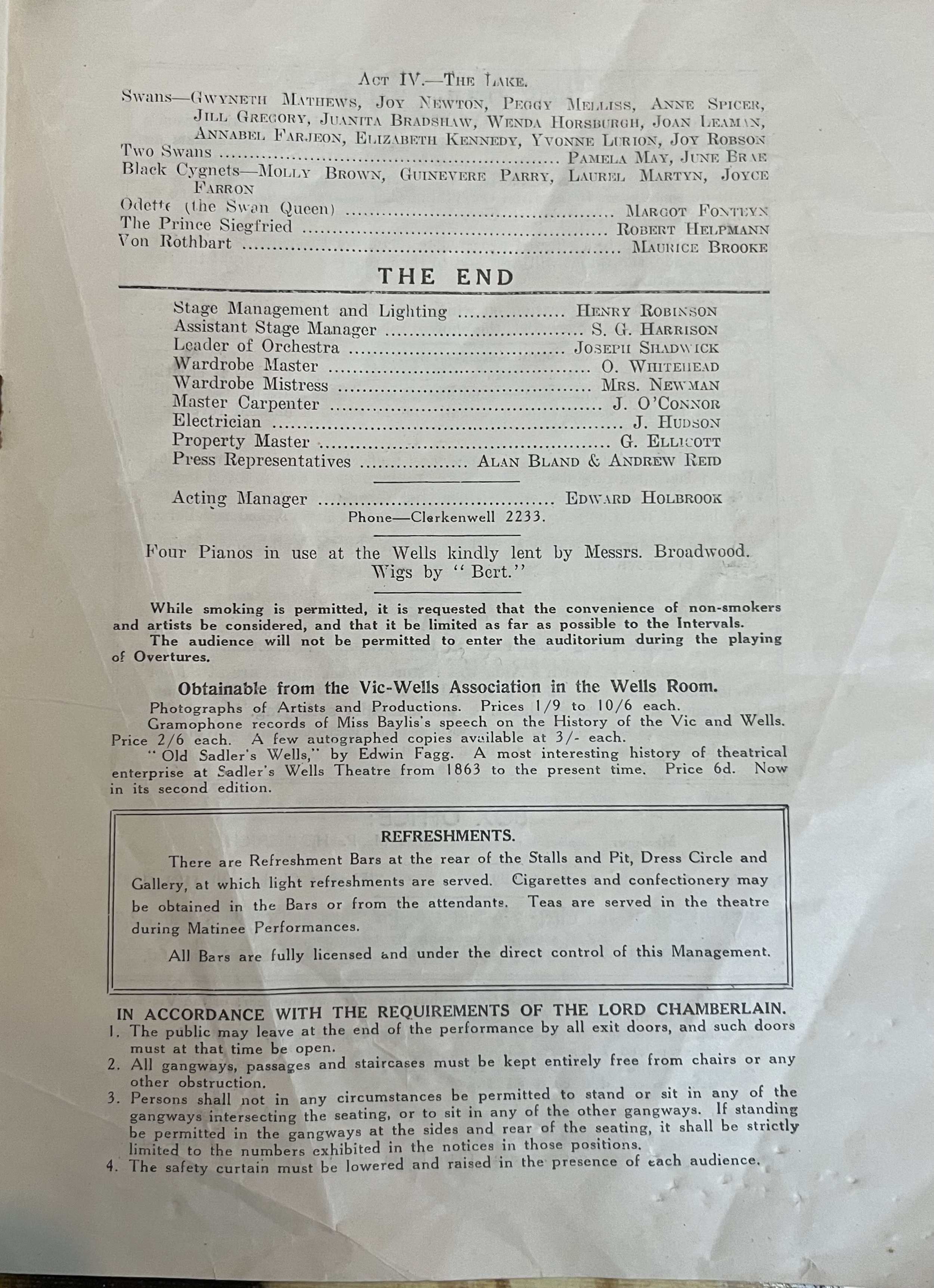

Joseph Shadwick, leader of the orchestra, was also a first violinist of note. More than fifty years after dancing Odette in “Swan Lake”, Pamela May would speak with gratitude of how beautifully he had played the violin solo in Odette’s adagio.

Curiously, no conductor seems to be mentioned. Why?

You could buy an unreserved seat for this “Swan Lake”, please note, for as little sixpence (2.5p). The priciest seats were seven shillings and sixpence (37.5p).

@Alastair Macaulay 2024

page 1 of the October 29, 1936, Sadler’s Wells programme for “Le Lac des Cygnes”

Page 2 of the Sadler’s Wells programme for the October 24 matinee, 1936, performance of “Le Lac des Cygnes”

Page 4 of the Sadler’s Wells programme for the October 24 matinee, 1936, performance of “Le Lac des Cygnes”

Page 6 of the Sadler’s Wells programme for the October 24 matinee, 1936, performance of “Le Lac des Cygnes”