The dancer Pauline Clayden, aged 100 in 2022, and her menagerie of roles.

The dancer Pauline Clayden reached a hundred years of age on Wednesday 12 October, 2022. When she was in her early thirties and dancing with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, she went to Frederick Ashton, laughingly, with a long list of the extensive menagerie of animal and bird roles she danced in the repertory of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet. She was a snake (Tiresias), a poodle (La Boutique fantasque), a fairy of the songbirds (The Sleeping Beauty), a goat (Sylvia), and many more. Ashton laughed, of course - he himself had choreographed some of those avian and animal roles for her; and he was personally fond of her. “She used to research them!” her great and longterm friend Julia Farron remarked in their old age, again with laughter.

Yet Clayden was also the dancer whom Ashton most often made second-cast to Margot Fonteyn in years when Fonteyn was the world’s most famous ballerina. It was she who danced Fonteyn’s roles in Dante Sonata (1940), Daphnis and Chloë (1951) and Homage to the Queen (1953). In the 1970s and 1980s, Ashton would say that he couldn’t see Daphnis without remembering Fonteyn’s Chloë (despite having cast Antoinette Sibley and Merle Park in the role himself) - but that wasn’t how he spoke in the 1950s, when he told John Martin of the New York Times that Pauline Clayden’s Chloë was one interpretation that kept him from missing Fonteyn. <1>

Once, on a North American tour, the management was obliged to replace Clayden in Homage to the Queen with Fonteyn - the Seattle audience that Saturday evening wanted the world’s most famous ballerina. When the news reached Clayden, she felt the double sensation of relief and disappointment: she was spared a tough role, but was also deprived of a great opportunity. When she reached her dressing room, she found that Fonteyn, famously considerate, had left her a bag containing a bottle of Arpège perfume: understanding Clayden’s sense of loss, she wanted to give this consolation. Clayden told the story almost fifty years later with nothing but admiration and gratitude for Fonteyn’s grace of spirit.

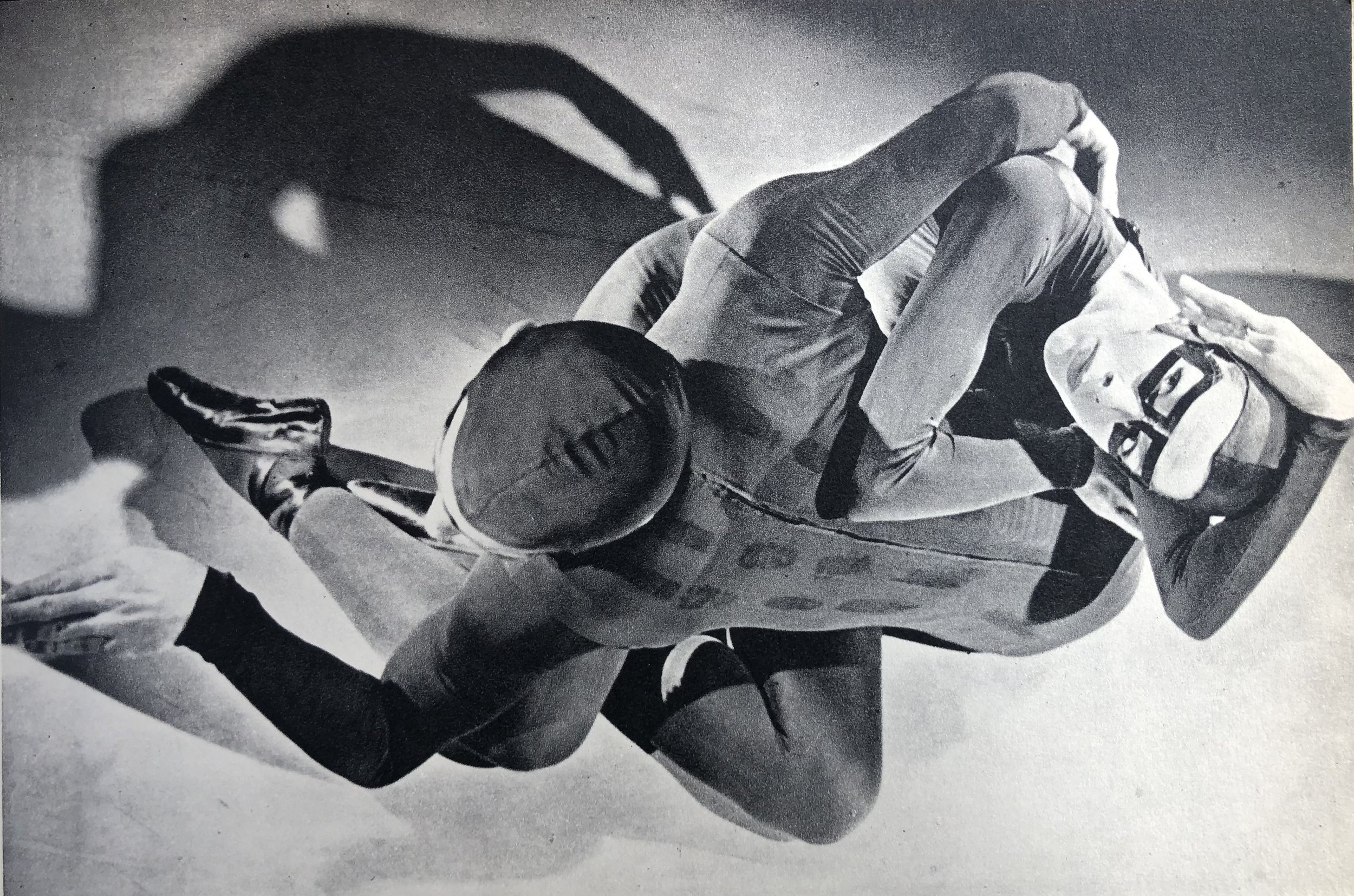

The animals and birds in Clayden’s repertory were not all studies in sweetness. Ashton’s Tiresias was a grand study in aspects of the cruelty of ancient Greek culture; Clayden and Brian Shaw were the two snakes whose couplings (see Ovid’s Metamorphoses) have a transfiguring effect on Tiresias when he beholds them. <2> Seeing them the first time, he is transfigured into a woman (Margot Fonteyn was the female Tiresias). Years later, seeing snakes copulating again, he is turned back into a man (John Field). So, when the Olympian gods Zeus and Hera (Jupiter and Juno) are arguing about his many adulteries and, in consequence, whether women derive more pleasure from sex than men (as Zeus claims), Tiresias is the only person personally qualified to comment from personal experience. When Tiresias concurs with Zeus - women enjoy it more - Hera in rage strikes him blind; but Zeus gives him the compensatory gift of prophecy - second sight. (It is not recorded whether the female snake enjoyed sex more than the male of the species, or even if either snake enjoyed it at all.)

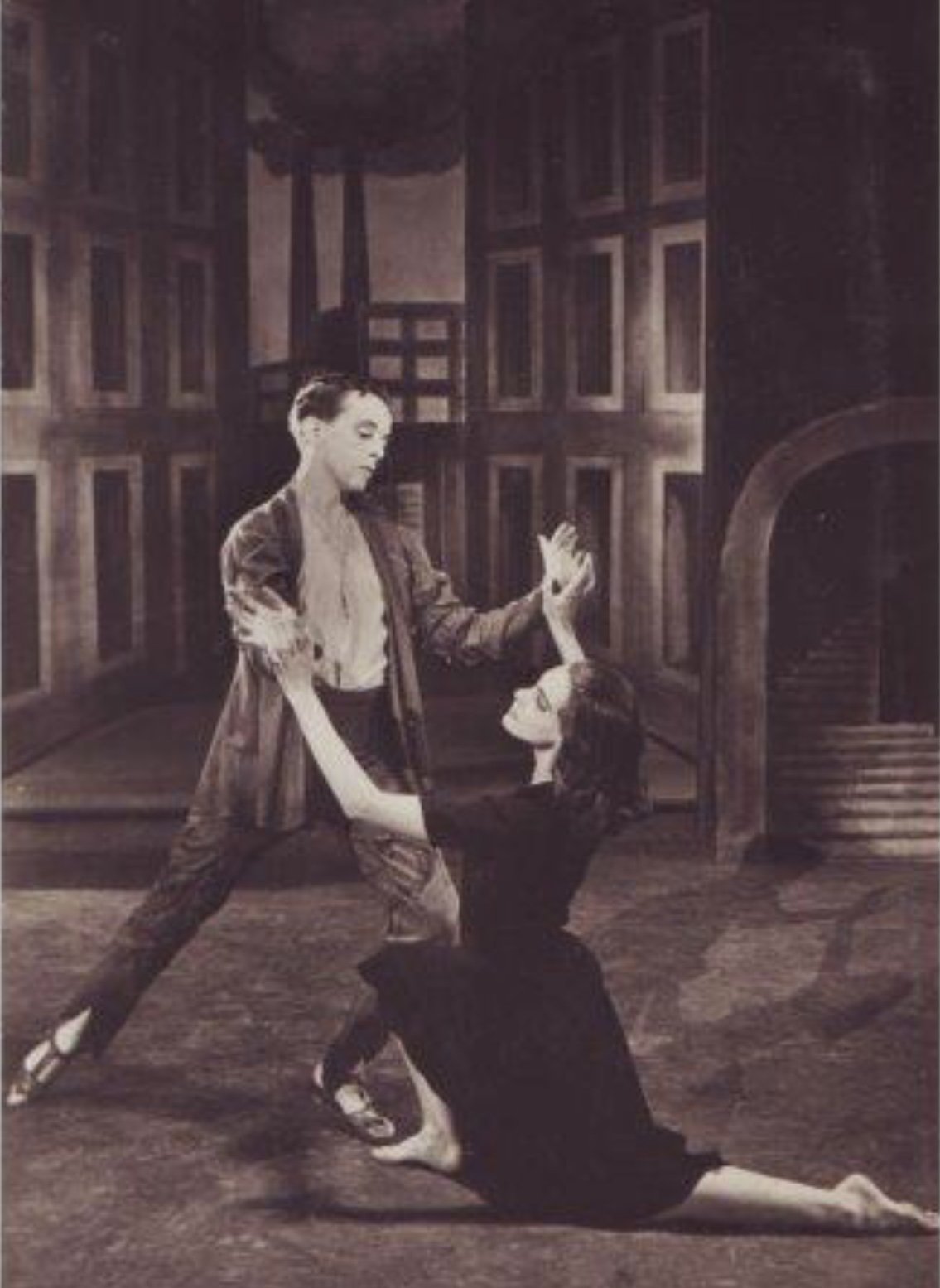

Clayden and Julia Farron first met as dance students at age six, around 1928, at the Cone School. Farron was the first to join the Sadler’s Wells or Vic-Wells Ballet, but Clayden, after dancing with Antony Tudor’s London Ballet and with Ballet Rambert, joined the Sadler’s Wells troupe in 1942. She had already danced and acted at Covent Garden, however; in 1939, she did walk-on roles in the Opera House productions of Turandot (she remembered the huge voice of Eva Turner in the title role on her hundredth birthday). Peggy van Praagh, who had spotted her among the Cone students, had recommended her to Tudor, who chose her rather than some of the Cone teachers’ own favourites. He cast her in a dance for four women in the Covent Garden Aida - the only time she worked with him, as he departed for the United States soon after. (Watching her, he told the other three, “That’s what I want!”) When she went to see Ninette de Valois about joining the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in 1942, she found that de Valois remembered her from student work at the Royal Academy of Dancing in the 1930s. (She also remembered that Ashton in the 1930s had made on R.A.D. students dances that probably were his preparation for his 1936 ballet Nocturne.) Once she was in the Wells company, her touching and vivid acting qualities won her the role of Ophelia, created by Robert Helpmann for Fonteyn in his Hamlet (1942). She then created the role of the Suicide in his Miracle in the Gorbals (1944), in which her immensely touching humanity made a lasting impression. (At first, he considered Fonteyn for the role, but then changed his mind. Fonteyn and he were the two busiest members of the company during the wartime years.)

Ashton had spent part of the War in uniform with the Royal Air Force. Once he was free to recommence work with the ballet, Clayden became one of the dancers whom he loved not just in solo roles but in ensembles. She was a Child in his Les Sirènes (1946), made for the Covent Garden stage to a new score by Lord Berners; and she was one of the twelve corps women in his original Scènes de ballet (1948), long treasuring (and often sharing copies of) the coloured diagrams she made of the elaborate kaleidoscope-like geometries through which the twelve moved to Stravinsky’s changing rhythms.

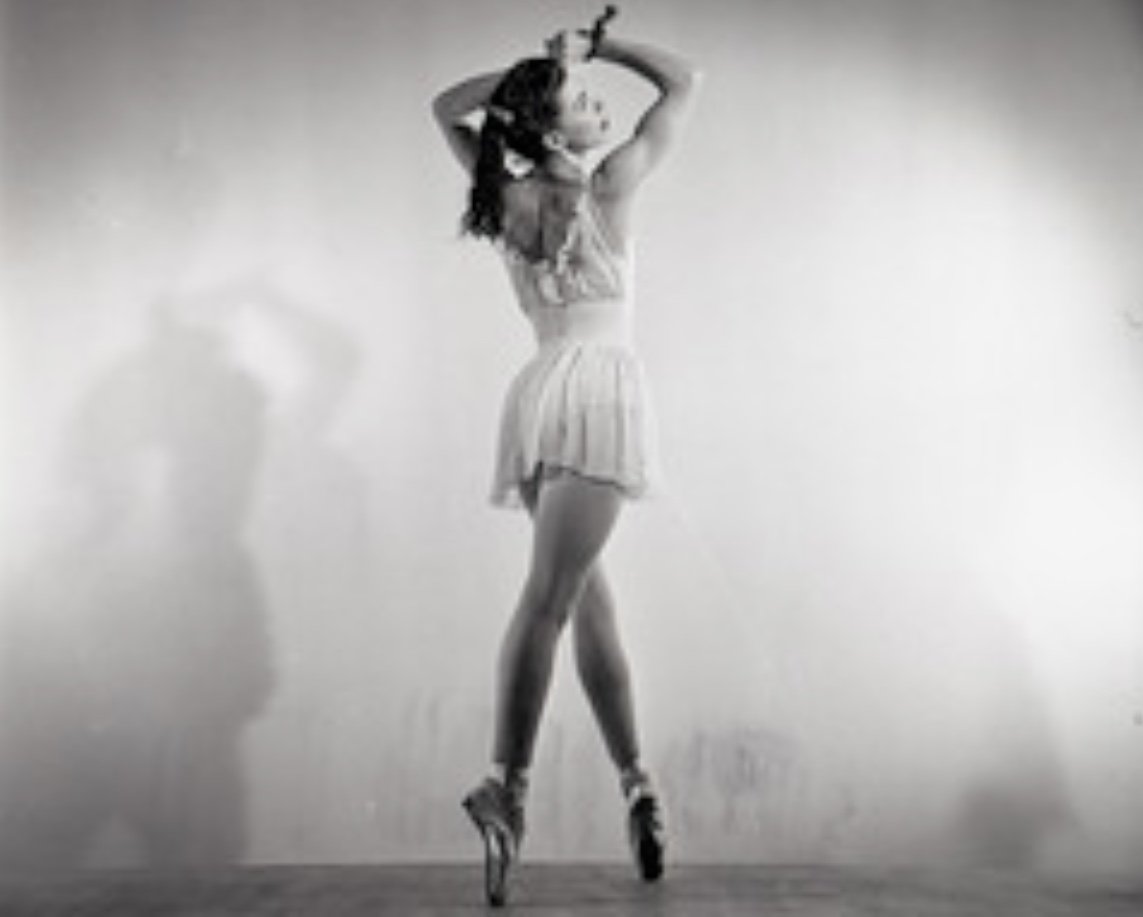

History knows her - for years this was all I knew of her - as the original Fairy Autumn in Ashton’s Cinderella (1948). There’s an irony here: actually, Ashton sketched the Autumn variation, with its memorable off-balance pirouettes, not on her - she was elsewhere, and he was busy making his first three-act ballet - but on Pamela May. When May, the original Fairy Godmother of that production, first told me this in 1997, I wondered if this was accurate - May’s memory, around age eighty, had developed occasional blips, though few - but Clayden herself, whom I met later that year, was happy to make sure I knew that Ashton had indeed originally created the variation on May. May never danced Fairy Autumn in performance, but she was a dancer Ashton liked and trusted, having known her for over fourteen years. May - who danced Odette, Aurora, Swanilda, Myrtha - was seen as a “ballerina”, in the snob ballet sense of the word; Clayden, danced a number of leading heroine roles, but not the classical-tutu kind, although she certainly did dance the Romantic title character of Giselle, for some the ultimate test of ballerinadom. On her hundredth birthday, Clayden recalled with pride how Ashton coached her for the role of Giselle, which she then danced four times at Covent Garden; and she treasured the letter of warm congratulations he wrote to her after her debut on the role.

May and Clayden performed together in many ballets, and were two of the six fairy godmothers on the Sadler’s Wells Ballet’s legendary first night at the Metropolitan Opera House in autumn 1949, in The Sleeping Beauty: May was the fairy of the Enchanted Gardens (no 2), Clayden of the Songbirds (no 4). The Songbirds has become the most tiresomely cute of the godmothers, all one-note ingratiation, but among the many reasons to watch Victor Jessen’s composite live film of 1949-1956 performances by the Sadler’s Wells Ballet on its North American tours (New York Public Library for the Performing Arts) is its view of Clayden in this variation. She doesn’t wear the fixed smile with which subsequent interpreters have turned this solo into trite cuteness. Instead the character’s brightness is present in her dancing, which becomes all the more eloquently sparkling when unsmiling.

When Clayden retired from the stage, she became Mrs Gamble; she now has children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. She continued to visit the ballet now and then: she has spoken with awe of watching Fonteyn, in her mid-forties, embodying the quintessence of youthfulness and poetry as Juliet. On visiting London from Devon, she tended to stay with Farron and Farron’s husband Alfred Rodrigues; I met her there more than once in the 1990s.

Her memory remains vivid, her ability to communicate and evoke keen, her enthusiasm touching. In the early 1990s, she helped to revive the Homage to the Queen Spirits of the Air pas de deux for an Ashton programme at Covent Garden; in 1997, she contributed to a South Bank tribute to the Vic-Wells Ballet; in 1999, she was part of The Fonteyn Phenomenon, the Royal Academy of Dance’s weekend-long tribute to the prima ballerina assoluta. When Jamie Tapper (coached by Monica Mason) demonstrated the pizzicato solo from Sylvia, Clayden’s immediate response was “Fred would have loved her!” She was too courteous to make a public issue of changes made (probably in the late 1960s, possibly by Michael Somes) to the two solos for Chloë, instead only complimenting the exquisite dancing of Sarah Wildor and coaching of Antoinette Sibley; but live film of Fonteyn c.1958 supports Clayden’s contention - those solos have been subtly changed in an important couple of details. When the Birmingham Royal Ballet revived Ashton’s Dante Sonata in 2000, she worked with her cold colleagues May and Jean Bedells to recapture the feeling of this lost work. Bedells was known as Miss Memory when it came to steps, but no ballet consists of steps alone, and Dante Sonata (a barefoot ballet danced with maximum intensity in the dark days of the Second World War) less than any: May and Clayden happily urged the Birmingham dancers into a fervour that connected movement into potent phrases and surging waves.

Earlier this century, she came to join her old friend Farron in London for various ballet functions. On one occasion, the two women, now in their eighties, shared a hotel room as they changed outfits. Bending over and finding themselves hard pressed to change their tights or some other clothing, they became helpless with giggles. Dancers all around the world love to laugh, but it’s fair to claim that laughter has played a greater part in the company history of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet and Royal Ballet than of any other troupe. But I don’t think of Clayden in terms of laughter alone; I think of her as all heart.

Thursday 13 October

1: Pauline Clayden as Chloë. Photograph: Baron

Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

2. Brian Shaw and Pauline Clayden as the snakes in Frederick Ashton’s Tiresias (1951). Photograph; Baron.

In Ovid’s telling of the Tiresias myth, it was the spectacle of two snakes copulating in a wood that had the effect of transforming the male Tiresias into a woman. Some years later, he saw snakes copulating there again - which now had the effect of transforming him back into a man. As planned by Constant Lambert and Ashton, the ballet Tiresias addressed the question “Which sex most enjoys sex?”, which in mythology Tiresias alone was qualified to answer from personal experience. It is not known whether the snakes of either gender enjoyed sex or how much.

3. Pauline Clayden and Brian Shaw as the copulating snakes in Frederick Ashton’s Tiresias (1951). Photograph: Baron.

.

4. Pauline Clayden and Brian Shaw as the snakes in Frederick Ashton’s Tiresias (1951). Photograph: Baron.

5. Pauline Clayden as the Betrayed Girl in Ninette de Valois’s ballet The Rake’s Progress (1935). Clayden’s quality of pathos was noted in several roles.

6. Pauline Clayden had only danced with the Sadler’s Wells Ballet for two years when Robert Helpmann created the role of the Suicide for her in his ballet Miracle in the Gorbals (1944), which had a commissioned score by Arthur Bliss and designs by Edward Burra. Helpmann himself created the Christ-like role of the Stranger. In this photograph, he is seen partnering Clayden.

7. Pauline Clayden as Chloë in Frederick Ashton’s Daphnis and Chloë (1951). Photograph: Roger Wood.

8: Pauline Clayden as Chloë in Frederick Ashton’s Daphnis and Chloë (1951). Photograph: Roger Wood.

9. Pauline Clayden backstage at Covent Garden in March 1951 in a photograph by Roger Wood. The Sadler’s Wells Ballet had just returned from a famous five-month 1950-1951 tour of North America, one year after its debut season in North America, bringing in revenue to both Covent Garden and the British exchequer (for which thanks were given in the House of Commons). It’s likely that Clayden here is costumed as Fairy Autumn, the role she had created in Ashton’s Cinderella (1948), with designs by Jean-Denis Malclès.

10: Pauline Clayden and Brian Shaw as those copulating snakes in Ashton’s Tiresias (1951)