Vyvyan Lorrayne Nieminen (1939-2022)

The ballerina Vyvyan Lorrayne (“who has a lot of Ys in her nayme,” wrote the American choreographer James Waring) has died, aged eighty-three. Born in April 1939 in South Africa but coming to the United Kingdom and devoting her main dance career to the two companies of the Royal Ballet, she was a lusciously serene classical stylist. In her late teens, she was part of the original cast of Frederick Ashton’s Ondine (1958). In her twenties and early thirties, she was part of his inspiration in choreography for four works, the first three of which remain in repertory today; the white pas de trois Monotones (Trois Gymnopédies) in 1965, Wednesday’s Child (“full of woe”) in Jazz Calendar (1968), the Ysobel/Arnold pas de deux in Enigma Variations (also 1968), and the erotic pas de deux “Siesta” in 1972.

Monotones became either Monotones I or Monotones II when Ashton added the pas de trois “Trois Gnossiennes” in 1966. (Probably Ashton’s title just meant that this was one work in two parts, but, because he had made the second part first, arguments remain fierce about which part is “I” or “II”.) Royal Ballet line had hitherto seldom asked women dancers to extend their legs above hip height (there were many important dancers who seldom did so throughout the 1970s), but with “Trois Gymnopédies” Ashton shook things up with his opening image: lights gradually revealed Lorrayne in the splits on the floor, her torso and head closely hugging one leg. As the men then raised her to vertical, she remained thus while they rotated her on point; she then fluently lowered her torso so that the rotation could continue, now with her head and torso hugging her lower knee. Later images in Monotones continued this poetic hyperextension, with one foot often raised to shoulder height. Cecchetti (or Stanislas Idzikowski on his behalf) had written in the 1920s that to extend legs above hip height was acrobatics rather than poetic artistry - but now in the 1960s here was the Royal Ballet, the world’s foremost exponent of Cecchetti style, showing how acrobatics could be liquefied into poetic line. Probably at some level of his consciousness Ashton was addressing the high-legged style of his contemporary George Balanchine; it’s impressive that he chose Lorrayne to do so. He was also creating a perfect image of what in the 1960s was called unisex, whereby differences between male and female were minimised: although Lorrayne danced on point and was lifted, much of the Monotones poetry lies in the parity of the sexes, with woman and two men often doing the same steps in unison or in series. (Images 1, 2, 3.)

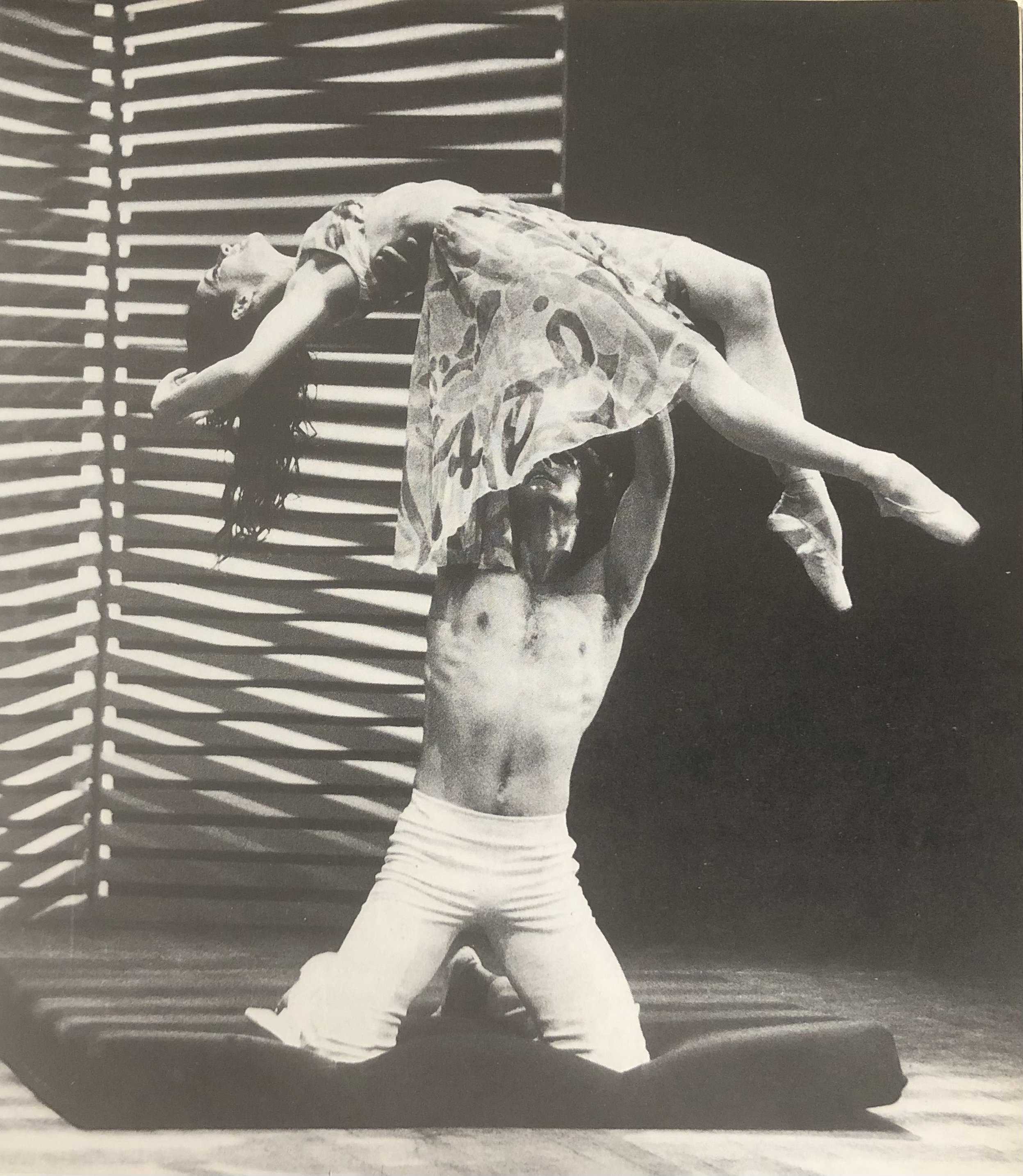

Jazz Calendar has had its fans; I confess I have never been among them - it’s a middle-aged trendy ballet. In Enigma, Lorrayne and Robert Mead as Richard Arnold were the young lovers whose mutual absorption demonstrate the kind of rapt love that the protagonist, Elgar, does not find in his own life. Ashton gave them the “Fred Step”, though for many years that was not noticed by audiences. (Images 4 and 5.) I would love to have seen Siesta (image 6), Ashton’s second treatment of a score by his friend and longterm collaborator William Walton; this one was made for an Aldeburgh celebration of Walton’s seventieth birthday dancers a few months earlier.

Three films survive of Lorrayne’s performance in Monotones, one in rehearsal: one of them shows Ashton rehearsing the first “Gymnopédie” (and the very start of the second) before its 1965 premiere. Two films survive of Lorrayne in the original cast of Enigma Variations, one a stage rehearsal in costume. An official film of Ashton’s Cinderella (1948), made around 1969 and starring Antoinette Sibley, Anthony Dowell, Ashton, Robert Helpmann, and Alexander Grant, shows Lorrayne as Fairy Summer, with entrances in all three acts. Another rehearsal film, from around 1970, shows Lorrayne as the first soloist in Raymonda Act III, gorgeously stretching her phrases with wonderful flow. In 2015, when I presented an evening of rare films of the Royal Ballet at the Bruno Walter auditorium of the New York Public Library, the New Yorker arts writer Claudia Roth Pierpont, a longterm ballet devotee, was especially thunderstruck by Lorrayne’s marvellous qualities of serene, lyrical composure in Monotones and in the Raymonda variation.

Monica Mason loves to tell how, in the later 1960s, she, Lorrayne, and their fellow South African soloist in the Royal Ballet, Deanne Bergsma - in January 1960, they had all danced in the world premiere of La Fille mal gardée - went to Ashton at the end of one season to request a full-length ballerina role in the coming year: Lorrayne was given Aurora (image 7), Bergsma Odette-Odile. (Mason, who loves to tell stories against herself but who also knew she had to work harder to please Ashton than others, tells how Ashton looked at her and said “So what do YOU want?” He gave her the role she requested, Odette-Odile, but not in a way that indicated enthusiasm for her potential. In the event, she danced Odette-Odile until 1980, when both Lorrayne and Bergsma had retired from ballerina roles.) What’s touching from Mason’s story is the way those three women went together to Ashton’s office and waited for one another to hear the good news.

In the 1970s, Lorrayne transferred to the touring Royal Ballet, which in due course became Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet (today’s Birmingham Royal Ballet), a company I saw often. If I remember correctly, Lorrayne there danced the Gypsy Girl in Ashton’s The Two Pigeons; she certainly danced Giselle. She also became a leading Balanchine dancer: she led its first performance of Concerto Barocco in 1977, she danced Terpsichore in Apollo and the Siren in The Prodigal Son, and was in The Four Temperaments, perhaps (here my memory falters) as the Third Theme. Her account of the Apollo pas de deux with Desmond Kelly in the title role was part of Margot Fonteyn’s 1979 TV series The Magic of Dance.

I am especially indebted to Lorrayne for a performance of the Coppélia Prayer variation that she gave in spring 1977 at Sadler’s Wells. Although the best accounts of Coppélia can be irresistible, this was, in Acts One and Two, one of the resistible others. I was twenty-one; the second interval brought a moment of crisis, as I thought seriously about going to dance far less frequently and spending my money more sensibly. Then Lorrayne, entering as Prayer, restored my faith in ballet. In particular, she executed one classic Petipa sequence with a purity and dynamic contrast that made me gasp. Prayer, in mid-variation, in profile to the audience, shows tendu front and bends low towards that extended foot, extending her arms almost as if meaning to use them to pick that foot up from the floor. Then transformation! Her foot lifted up by itself, her body pivoted on its supporting leg into relevé first arabesque, and an inward-facing intimate position had miraculously become a wonderful beacon of flowing line that filled the stage and theatre.

Returning to her native South Africa, she became an important teacher at the National School of the Arts, Johannesburg. Bradley Shelver, artistic director of the Joffrey Ballet Concert Group, studied with her there for six years; he is among those who has paid tribute to her today. (“One of my most influential ballet teachers passed away today. She had wisdom, encouragement, passion and the most nurturing way. Vyvyan Lorrayne Nieminen you will be missed. You empowered and inspired many generations and I am so grateful to have been your student… For six years, you guided, mentored, and inspired me. Rest in Peace, Grande Dame. You nurtured the love of ballet in so many of us.”)

She joined Facebook in her later years. In her late seventies, now Vyvyan Lorrayne Nieminen, while I was working in New York and she remained in South Africa, I was able to tell her of how life-changing that Coppélia moment had been. I was also able to tell her of the impression made on many by her dancing on film at the New York Public Library. My gratitude endures.

Monday 8 August

1.Frederick Ashton (right) rehearsing the original cast of “Monotones - Trois Gymnopédiee”(1965: left to right, Anthony Dowell, Vyvyan Lorrayne, Robert Mead. Getty Images.

2. Left to right, Anthony Dowell (alighting from a jump), Vyvyan Lorrayne, Robert Mead in Frederick Ashton’s “Monotones - Trois Gymnopédies”.

3. Left to right, the original cast of Frederick Ashton’s “Monotones - Trois Gymnopédies”: Anthony Dowell, Vyvyan Lorrayne, Robert Mead.

4. The closing “photograph” tableau of Frederick Ashton’s “Enigma Variations” (1968). Robert Mead and Vyvyan Lorrayne are on the left as Richard P. Arnold and Isabel Fitton (“Ysabel”).

6: Vyvyan Lorrayne lifted by Barry McGrath in Frederick Ashton’s “Siesta” (1972), made as “a birthday card” for Ashton’s longterm friend and collaborator, the composer William Walton, who had had his seventieth birthday earlier that year.

8: Vyvyan Lorrayne, Antoinette Sibley, Deanne Bergsma, three of the young women who reached ballerina status under Frederick Ashton’s directorate in the 1960s.

9: Vyvyan Lorrayne as the Siren in Balanchine’s “Prodigal Son” with Desmond Kelly as the Son, Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet, late 1970s.

10: A 1970s photograph of Marion Tait, Lesley Collier, Vyvyan Lorrayne before the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

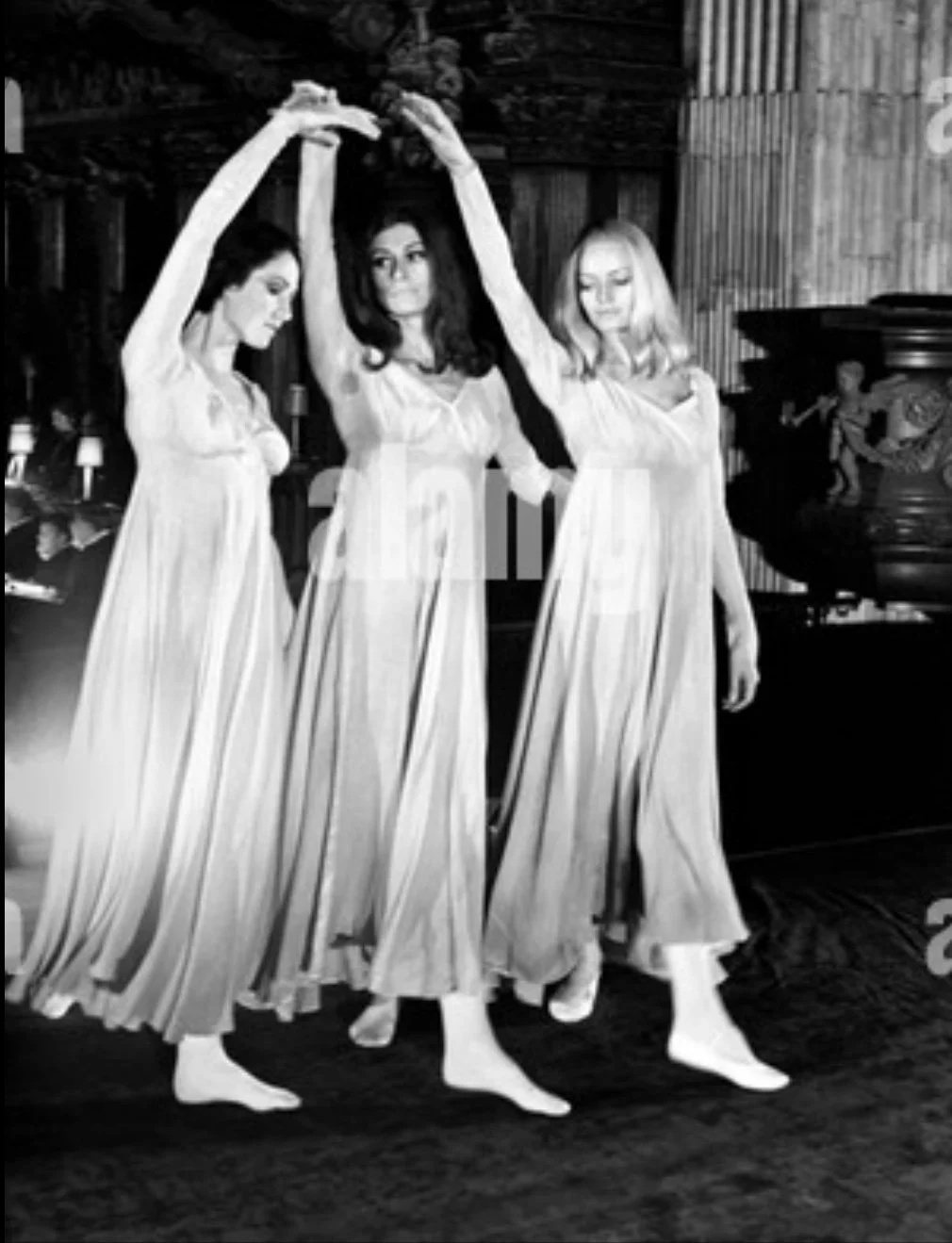

11: A curious 1965 photograph, by G.B.L.Wilson, of the Fairy Godmother (Annette Page, centre) in Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella, surrounded by (left to right) Merle Park (Fairy Autumn, kneeling), Deanne Bergsma (Fairy Winter), Vyvyan Lorrayne (Fairy Summer), Antoinette Sibley (Fairy Spring). These costumes must have been from the David Walker designs new in 1965; I say “curious”, because the fairies’ costumes were subsequently modified in that production.