The skin colour of George Balanchine’s Apollo: Black History Month in Dance, 2021

The history of the title role of George Balanchine’s “Apollo” makes a curious one for Black History in dance and for skin colour in ballet altogether. Photographs show us that Balanchine’s original Apollo, Serge Lifar, danced it in 1928 with a rich suntan that contrasted with the white skin of his muses, as if Apollo, the god of the sun, should be darkened by the sun. To the Paris Opera Ballet, Apollo then became a role to be danced with darkened skin: playing the role in 1947, the Paris Opera étoile Michel Renault wore dark body makeup that came off on the white tunic of his Terpsichore, Maria Tallchief.

By contrast, in New York, Balanchine cast a series of pale-skinned white dancers as Apollo from 1937 onward. (His most longterm Apollo, Jacques d’Amboise, danced the role in black tights, as did some other interpreters of the role.) Balanchine, however, had no one physical type for the role: the few to whom he gave it included tall long-limbed men and short compact ones. It was not one of the roles he gave to Arthur Mitchell, but we may suppose that this was for reasons of character and temperament rather than race; and during Mitchell’s time at New York City Ballet, the role of Apollo was usually taken by d’Amboise. When Mitchell and Karel Shook founded Dance Theatre of Harlem, “Apollo” was not one of the numerous Balanchine ballets danced by that company.

Probably the first instance of a black Apollo, in Balanchine’s ballet, occurred in 1969, in the Netherlands. The African American dancer Campbell Sylvester had trained at the School of American Ballet in the 1950s and had joined the short-lived Negro Ballet in 1957, but no other American company employed him; in 1960, he therefore joined Dutch National Ballet, which cast him as Apollo in 1969. (A photograph of him - see 176 - was published in “Dancing Times” in 1970. My thanks to that magazine’s last editor, Jonathan Gray, for drawing this photograph to my attention.) Raven Wilkinson later remarked of Campbell that he was an outstanding example of an African American danseur noble, one that it was too bad so few Americans ever observed. Perhaps nobody noticed at the time was that Campbell thus became the world’s first black Balanchine Apollo.

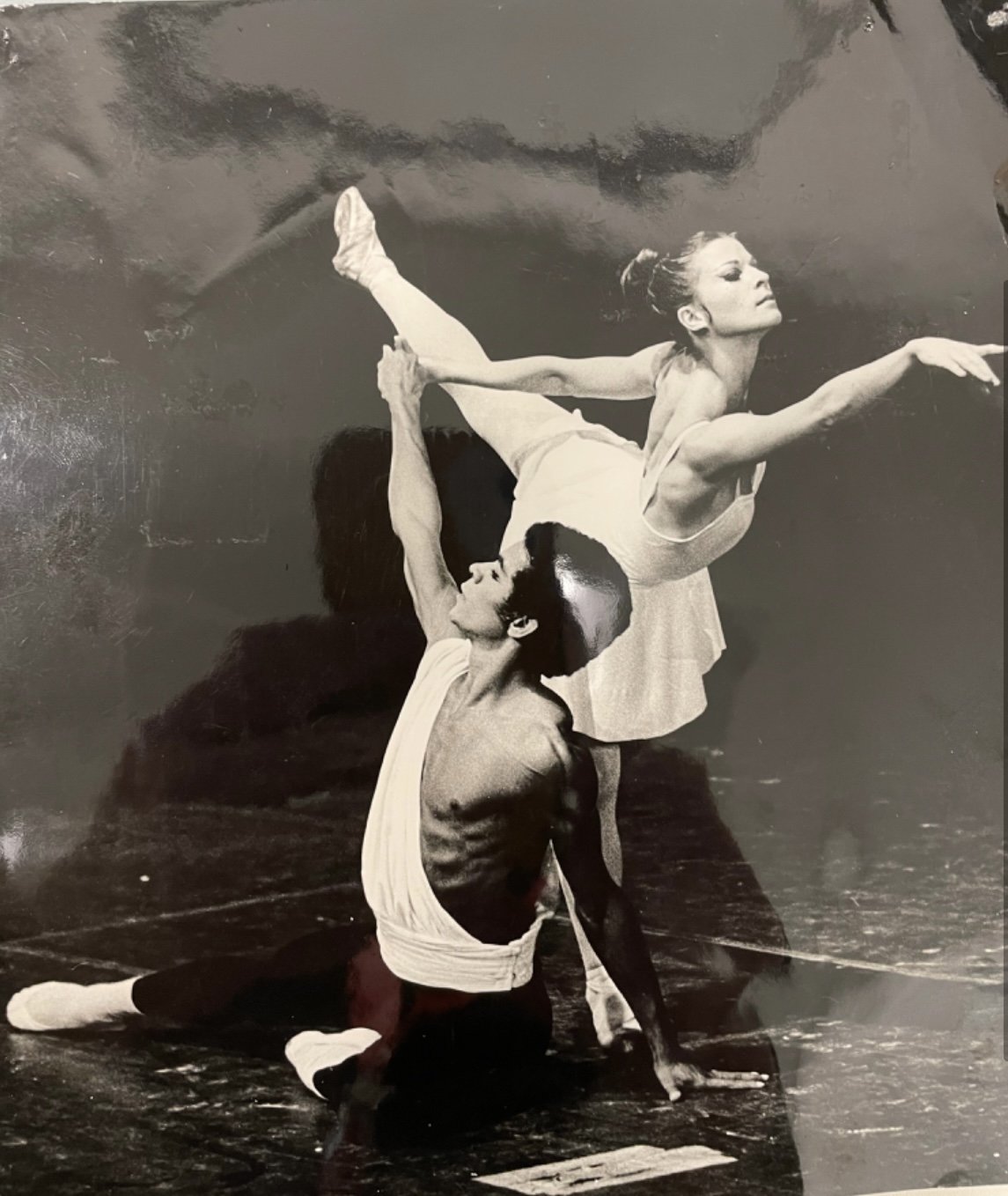

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Harlem company danced in all three of London’s most prestigious dance theatres - the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, the London Coliseum, Sadler’s Wells Theatre - with the result that, when the Royal Ballet began to invite black dancers to make guest appearances in leading roles, it made the invitations to Harlem dancers. First were Christine Johnson and Ronald Perry as the Sugarplum couple in “The Nutcracker”, in 1990. In 1991, Eddie J. Shellman came to dance “Agon” with the Royal’s own young star ballerina, Darcey Bussell. (In 1993 and 1994, when she went to dance “Agon” with New York City Ballet, she was partnered by a white man, Lindsay Fischer.) Then in 1993 Shellman returned to the Royal, now as Apollo, with Bussell his Terpsichore (photograph 177). He alternated with Irek Mukhamedov, the Russian star who had become a principal of the Royal in 1989.)

Almost as historic is that the Royal was the first to instigate further casting of black dancers in the role. In the twentyfirst century, Carlos Acosta danced Apollo as a resident principal of the Royal Ballet between 2003 and 2013.

It’s curious how long it has taken America’s foremost companies to follow suit. In 2011, the black soloist Craig Hall danced Apollo with New York City Ballet (photo 178), but only at a one-off Dancers’ Choice performance, never in regular repertory. Finally in January 2019 City Ballet cast its exceptional young principal Taylor Stanley in the role (photo 178) in August 2019, Calvin Royal III danced Apollo at the Vail International Dance Festival, before dancing it in New York with American Ballet Theatre that October (photo 179B).

The significance of Apollo among male parts is immense. Apollo is both god and artist, apprentice and protagonist, singled out for art and leadership even before he learns his craft, and given maximum exposure as he proceeds to maturity. “Everyone should dance Apollo!” Ib Andersen (the last City Ballet principal to be cast and coached in the role by Balanchine) exclaimed in 2018: “It’s the best feeling in the world.”

But it’s not for a role for all men, or for all Apollonian men: some of the most seemingly Apollonian of dancers have never danced it, while other otherwise Apollonian men have been wrong for it. And what’s “Apollonian”? Balanchine (1904-1983) seems to have given the role only to those men (of whatever physical type) in whom he spotted the spark of divine fire, some short, some tall. In 2010, Peter Martins, ballet-master-in-chief at New York City Ballet, after announcing that he would revive “Apollo” for the company after a two-year gap, remarked that he now understood why Balanchine had sometimes been reluctant to revive the ballet: the line of male dancers outside his, Martins’s, office was suddenly lengthier than any before, all ambitious for the role. We have seen few great Apollos of any colour, but it’s good for everyone that the role is now being given to dancers black and white alike.

Saturday 27 February, 2021, revised Tuesday 24 October 2023

176. Sylvester Campbell as Apollo in 1969 with Dutch National Ballet. Olga de Haas is Terpsichore. Photograph published in “Dancing Times”, 1970.

177. The Royal Ballet in 1993: Eddie J. Shellman as Apollo; Darcey Bussell as Terpsichore.

178. Craig Hall, New York City Ballet’s first black Apollo, in 2011. This was an isolated Dancer’s Choice event, not casting as regular repertory.

179A. Taylor Stanley as Apollo, New York City Baller, early 2019.

179B. Calvin Royal III as Apollo, American Balet Theatre, fall 2019. Royal had previously danced the role at the Vail International Dance Festival in August 2018.