Balanchine the Dramatist

This is an annotated version of Balanchine’s Plot, an essay published by the young quarterly Liberties (USA) and published in its volume 1 no 2 in early 2021.

I.

The great choreographers have all been more than dancemakers, none more so than George Balanchine (1904-1983). He was in truth one of the supreme dramatists of all theatre, but, because he specialized in plotless ballets with no named characters or written scenarios, this aspect of his genius has gone largely unexamined. Instead everyone accepts the notion – it has become the greatest platitude about him -- that he was the most musical of choreographers – a notion that, for all his musical virtues, should be qualified in several respects. Even at this late date, there is much about Balanchine that we still need to understand.

His dance creations often eliminate ingredients that others regarded as the quintessence of theatre. The performers of his works are verbally and vocally silent. Facial expressions and other surface aspects of acting are played down. In many of his works, costumes are reduced to an elegant minimum: leotards and tights, often only in black and white; or simple monochrome dresses or skirts. In particular, he pared away layers of the social persona of his dancers, so that on his stage they become corporeal emblems of spirit. Liebeslieder Walzer, for example, his ballet from 1960, has two parts. In the first part <illustration 2>, the four women wear ballgowns and heeled shoes; in the second <illustration 3>, they dance on point and in Romantic tutus. “In the first act, it’s the real people that are dancing,” Balanchine told Bernard Taper. “In the second act, it’s their souls.” <1>

His Serenade (1934), set to Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings, is a masterpiece for many reasons. No ballet is more rewatchable. (If you don’t know it, there are at least two complete versions on YouTube. <2>) Several of its configurations and sequences are among the most brilliantly constructed in all choreography. Pure dance is threaded through with threads of narrative, suggesting fate and chance, love and loss, death and transcendence. It consists almost as much of rapturous running as it does of formal ballet steps. Classicism meets romanticism meets modernism. The opening image is justly celebrated, a latticed tableau of seventeen women who, in unison, enact a nine-point ritual like a religious ceremony. At its start, they are extending arms as if shielding their eyes from the light; at its end, their feet, legs, torsos and arms are turned out, open to the light like flowers in full bloom. This has often been interpreted as transforming them from women <illustration 1> into dancers. Taking Balanchine’s point about Liebeslieder, we might go further and say that the opening ritual of Serenade transforms them into souls.

Serenade also has an important place in history as the first work Balanchine conceived and completed after moving to the United States of America. A serial reviser of his own work, he kept adjusting it for more than forty years <illustration 4><3>Only around 1950 did it begin to settle into the form we know now, with its women in dresses ending just above the ankle. (The nineteenth-century Romantic look of those dresses is now definitively a part of Serenade. It remains a shock to see photographs and film fragments from the ballet’s first sixteen years, with the women’s attire revealing knees and even whole thighs. Still, if you see the silent film clips of performances by Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo in 1940 and 1944, you can immediately and affectionately recognize most of their material as Serenade.) For more than fifty years, Serenade has been danced by non-Balanchine companies around the world; in the last decade alone, beloved by dancers and audiences, it has been performed from Hong Kong to Seattle, from Auckland to Salt Lake City.

Even so, for musical purists this is an unsatisfactory ballet. Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings, composed in 1880, was a score in which this notoriously self-critical composer took immediate and lasting pride: he conducted it many times, not only in Russia but in many other countries too. He made it in cyclical form: his opening movement, called Piece in the Form of a Sonatina, opens and closes with powerful series of descending marcato scales, while the final movement returns to descending scales with a jaunty Russian theme. Throughout the work, the composer plays with musical effects as if he had the alchemist’s stone – taking the weight off those descending scales by changes of orchestration in the first movement; reversing them in the climbing legato scales of the third movement, the Elegy; and returning at the end of the fourth movement to the work’s opening scales, only to accelerate and show how closely they are related to the Russian theme. Tchaikovsky was deeply proud of his status as the most internationally successful Russian composer of all: by naming the final movement Tema Russo (Balanchine called it “Russian Theme” in a book about his ballets<4>) he reminds us that, if he had any extra-musical agenda in his Serenade for Strings, it was to win renown for the music of his nation.

Yet Balanchine made Serenade to just Tchaikovsky’s first three movements. He was following the precedent of Eros, a 1916 ballet by Michel Fokine which Balanchine had known in Russia. (Although Balanchine remarked at the end of his life that he had not much liked Fokine’s ballet<5>, he took several other ideas from it for Serenade.) A devotee of Tchaikovsky’s music, he may have omitted the concluding Russian Theme in 1934 merely because his new American students did not yet have the speed and the brilliance that his vision of the Russian Theme would require; later in the decade, he sketched the Russian Theme with Annabelle Lyon, one of his original 1934 group, but was unable to stage it<6>. He added the Russian Theme in 1940, by which time the youngest of his 1934 students, Marie-Jeanne, had now acquired the virtuosity he wanted to create its leading role. But not as a finale, as in the musical score: he inserted it between the second and third movements, thus erasing one of Tchaikovsky’s most magical transitions, beginning the fourth movement with the same quiet high notes that ended the third. How curious: Tchaikovsky ended his Serenade with a high-energy and dance-friendly finale, yet Balanchine preferred to close his Serenade with the Elegy, which seldom sounds like dance music. His reason, I think, was dramatic: by ending his ballet with Tchaikovsky’s elegiac penultimate movement, he found a way to conclude the work with a passage into the sublime. A number of Balanchine’s ballets end with the leading character departing for a new world. This is one of them.

Balanchine’s Serenade is quite as marvellous a work as Tchaikovsky’s score. No, even more so. Yet it’s not a faithful rendition of Tchaikovsky’s original. Instead the choreographer gave it its own enthralling musicality. Balanchine took the liberty of revising this score – as he did with scores by several composers, but with none so much as Tchaikovsky – because he was impelled by a dramatic vision. If, as I say, Serenade is the most rewatchable ballet ever made, it is because, from first to last, the work is an exercise in theatrical drama. Its narrative is mysterious but undeniable. The work is an abundant kaleidoscope of changing patterns, images, encounters, communities; a tapestry of stories that movingly suggest fate, love, loss, death, transcendence, and the group’s support for the individual. It is also an object-lesson in ambiguity and metamorphosis.

II.

When Balanchine arrived in the United States in late 1933, at the invitation of Lincoln Kirstein, he was not particularly associated with pure-dance works. In Western Europe, between 1925 and 1933, he had staged Ravel’s L’Enfant et les Sortiléges, Stravinsky’s Apollo, Prokofiev’s Prodigal Son, the Brecht-Weill Seven Deadly Sins <illustration 5>, and other highly singular narratives. Once in New York, he abounded in ideas for new ballets, many of which Kirstein reported in his diary. The projects of which he told Kirstein - sometimes he developed them for days or months - include versions of the myths of Diana-Actaeon, Medea, and Orpheus, an idea of his own named The Kingdom without a King, a new production of The Sleeping Beauty, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Virgil Thomson was to compose the score), Brahms’s Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel, Schumann’s Andante and Variations, a ballet of waltzes starting with those of Joseph Lanner, and The Master Dancers, a Balanchine idea based upon the story of a dance competition. (Most of these ideas were never fulfilled, though some were probably inklings of dances that Balanchine choreographed much later.)

Kirstein’s entry for May 6, 1935 gives us a vivid glimpse of the dramatically imaginative workings of Balanchine’s mind in this note about a Medea ballet that never saw the light of day:

“Bal. thought of a new ending for Medea: Her dead body is executed by the troops : told me a story or idea for another pantomime : a court-room where the condemned is faced by a three headed judge. She is two in one like AnnaAnna: As evidence, objects like Hauptmann’s ladder are brought in – The whole crime is reconstructed. She is declared guilty, though innocent... Bal said it shd be like Dostoevski.”<7>

Anna-Anna had been the London title of The Seven Deadly Sins, in which the dancing Anna and the singing Anna express different aspects of the same person<illustration 5>. Balanchine never lost this flair for radically reconceiving old radical stories. In that work and others, he was addressing different layers of being, in much the same way that D.H.Lawrence, when writing The Rainbow, described to Edward Garnett about how it differed from his earlier Sons and Lovers:

“You mustn’t look in my novel for the old stable ego – of the character. There is another ego, according to whose action the individual is unrecognizable, and passes through, as it were, allotropic states which it needs a deeper sense than any we’ve been used to exercise, to discover are states of the same single radically unchanged element. (Like as diamond and coal are the same pure single element of carbon. The ordinary novel would trace the history of the diamond – but I say ‘Diamond, what! This is carbon.’ And my diamond might be coal or soot, and my theme is carbon.)”<8>

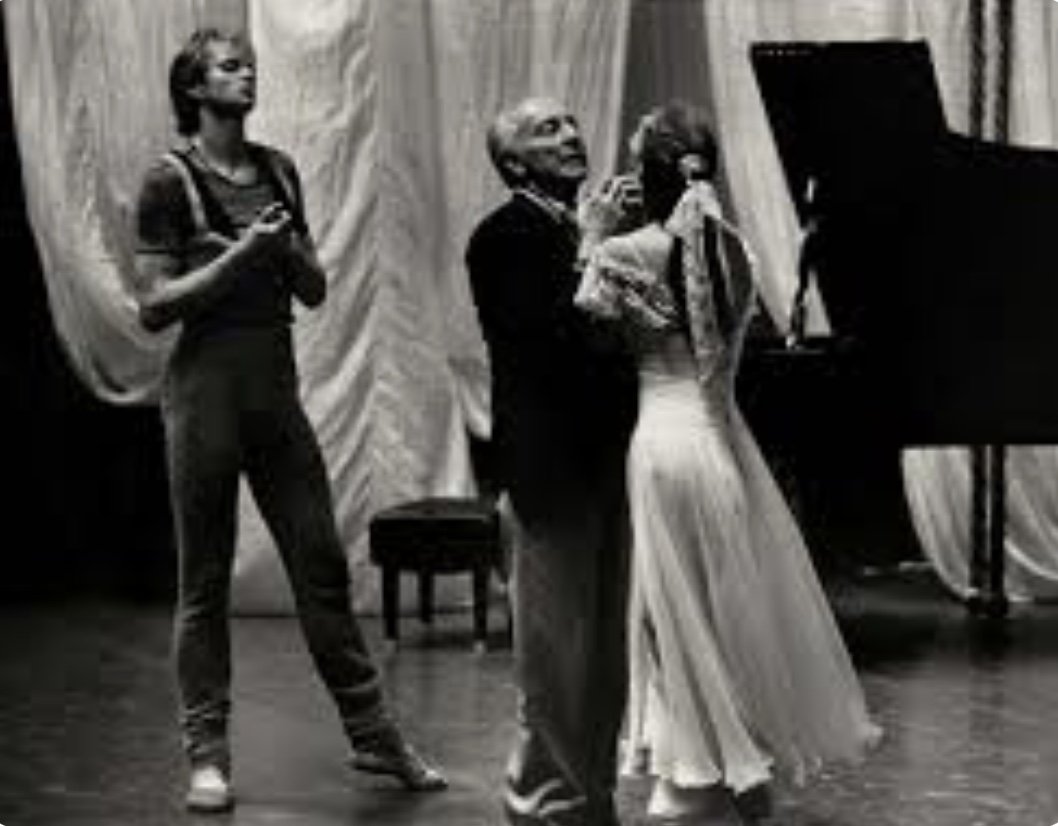

The Balanchine ballets that seem to be reflections solely of their music – the specialty of the long American phase of his career, especially from 1940 onward – do not dispense with narrative. Not at all. They supply multiple narratives or fragmented versions of a single narrative. In one of his last masterpieces, Robert Schumann’s “Davidsbündlertänze” <illustration 6> in 1980, four male-female couples express diverse aspects of Schumann and his relationship with Clara, his wife and muse. As in Liebeslieder Walzer, Balanchine introduced the women in heeled shoes but then brought them back onstage on point, as if setting their spirits free. The complication of having four Roberts and four Claras <illustrations 7, 8> suggests the tragic splintering of the composer’s tormented and echoing mind: not Anna-Anna but Robert-Robert-Robert-Robert alone with Clara-Clara-Clara-Clara. Here’s multiple personality syndrome at its most poetic.

There are ballets in which Balanchine moves from showing his dancers as “the real people” to “their souls”without employing any change of costume or footwear. The outer movements of Stravinsky Violin Concerto, from 1972, the Toccata and the Capriccio, are festive, with four leading dancers (two women, two men) each joined by a team of four supporting dancers. The mood is largely ebullient. But then Balanchine brings the concerto’s two-part centrepiece, Aria I and Aria II, indoors, as it were, and into a marital bedroom for scenes of painfully raw, almost Strindbergian, intimacy. Different male-female couples dance each Aria, though Balanchine may have seen them as different facets of the same marriage.

The woman of Aria I is amazingly and assertively unorthodox, constantly changing shape, using the man’s support to be even less conventional <illustration 9>. In the most memorable image, she does bizarre acrobatics, bending back to place her hands on the floor and then turning herself inside-out and outside-in, fluently flipping through convex/concave/convex shapes in alternation. The duet is an unresolved struggle, not so far from the marital strife of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The woman of Aria II, much needier, is more subtly demanding. Stravinsky’s music has a repeated chord that sounds like a sudden shriek. Here the woman strikes an X pose, balanced precariously on the points of both feet with legs and arms outstretched. She’s both confrontational and insecure: it may be the most passive-aggressive moment in all Balanchine, as if the wife is demanding his support. As he goes to her, her knees buckle inwards <illustration 10>; when he catches them before she crumbles further, it seems as if she has mastered the way to pull him back to her assistance. It works. He plays the protective husband that she needs him to be; she is the grateful wife. There are moments of touching harmony between them – one when he shows her a panorama view with his arm over her shoulder, another when he covers her eyes and gently pulls her head back. The tension between his control and her passivity is part of the scene’s poignancy.

Serenade, too, tells multiple stories, or gives us dramatic situations that we are free to interpret in many ways. Balanchine’s narrative skill is such that few observers follow this ballet without tracing some element of plot in it somewhere. This is a ballet about the many and the one: about how a series of individual women emerge from the larger ensemble, sometimes in smaller groups and occasionally with men, but recurrently supported by the corps. Over the years - as with no other ballet - Balanchine amused himself with the redistribution of roles: there may have been as many as nine soloists in the 1930s performances, but in the 1940s he gave most of the largest sequences to a single ballerina. (Perhaps he privately thought of it as one woman; in his late years he told Karin von Aroldingen that the work could be called Ballerina.<9>) Yet there are moments when we see more leading women than one: there are tiny solo roles of great brevity, and in most productions all the women have been dressed identically. Again and again, Balanchine makes us ask, Who is this? What is happening to her? At times the answer scarcely matters; at others it matters greatly.

After a string of quasi-narrative situations, the final Elegy has always seemed the most suggestive of plot. It is profoundly moving because of the story it seems to tell. At its start, one woman is lying on the floor as if abandoned, bereft, or even dead. A man is led to her by another, fate-like, woman, who keeps his eyes and chest covered with her hands until he reaches his destination. The woman on the floor is the first person he sees; he is the first person she sees<10>. Balanchine presented the charged moment of their eyes meeting, with the man and woman framing each other’s faces with their arms, as a quotation from Canova’s extraordinary sculpture Psyche Awakened by Cupid’s Kiss, to which he drew the attention of some dancers<11>. Although this Canova quotation was itself derived from Fokine’s ballet Eros, it must have gratified Balanchine that the three chief versions of the statue are to be found in the main museums of the three chief cities of his career: St Petersburg’s Hermitage, Paris’s Louvre, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art <illustration 11>.

What follows between the figures – we can also call them the principal characters - seems like love. But just as Diana of Wales once observed that “there were three of us in this marriage,” so this love is shadowed by the constant presence of the female fate figure known in Balanchine circles as the Dark Angel <illustration 12>. Other women pass through, one of them lingering for a while. (The dancer Colleen Neary told me that Balanchine once jokingly likened these three women to the man’s wife, his mistress, and his lover. And added, “Story of my life!”<12>) An unhappy ending ensues. With startlingly swift force, the man lowers his “wife” to the floor. The Dark Angel stands aloof, averting her eyes from this tragic parting. She then returns as the agent of fate, beating her arms like mighty wings; once again she covers his eyes and chest with her hands; and she leads him offstage as if continuing the same diagonal paths by which they entered.

All this is a powerful re-telling of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice – a myth to which Balanchine returned between 1930 and 1980, using music by Gluck <illustration 13>, Offenbach, and Stravinsky <illustration 14>, and to which he made many autobiographical connections. In the ancient myth, Orpheus, artist and husband, loses Eurydice when she is bitten by a snake. He is permitted to enter the realm of the dead -- the Elysian Fields, the realm of the blessed -- and to lead her back to life on condition he does not look at her until they both have reached the ground above. At the last moment, however, he looks back, and loses her forever. The Elegy in Serenade prolongs and suspends the bittersweet moment of their eyes’ climactic meeting.

Unlike Balanchine’s other treatments of the Orpheus story, this one leaves us with Eurydice, the dead Eurydice that Orpheus has lost a second time. She is left by him on the floor exactly where she had been when he found her. When she rises, she parts her hands before her eyes, as if to ask if “Was that all a dream?” Just at this point, in the confusion of her awakening, she is joined by a sisterhood: a small cortège of the women who have characterized the whole ballet. In grief, she embraces one of them -- known as “the Mother” -- before kneeling and opening her arms and head to the sky, in a gesture of utmost resignation and acceptance. As the ballet ends, she is carried off like a human icon, by three men, while her sisters and her “mother” flank her. She opens her arms and face to the skies in a backbend as the curtain falls, entering a new plane of existence.

It takes several viewings before you realize that she, opening her arms and head this way to the heavens, is repeating what all seventeen women did in the ballet’s opening sequence. One reading of Serenade, therefore, is that all of its dramatic narrative is set in the Elysian Fields. Those dancers we see at the beginning are ghosts consecrating themselves, as if saying their vows.

III.

It’s revealing that the eyewitness accounts of the first day’s rehearsal of Serenade differ: not contradicting one another, but concentrating on different facets. Kirstein wrote in his diary:

“Work started on our first ballet at an evening ‘rehearsal class.’ Balanchine said his brain was blank and bid me pray for him. He lined up all the girls and slowly commenced to compose, as he said – ‘a hymn to ward off the sun.’ He tried two dancers, first in bare feet, then in toe shoes. Gestures of arms and hands already seemed to indicate his special quality. “<13>

To Balanchine, looking back in the 1950s and 1960s, the compositional issue had been the fortuitous presence of seventeen women.<14> Probably he knew anyway from the music that he wanted them to start with a slow arm ritual – but how do you take this unwieldy prime number, seventeen, and arrange it in space? His brilliantly geometric solution of this arithmetical problem was the diagonally latticed formation, a pair of two diamond shapes conjoined. These obviate the usual vertical lines of ballet corps patterns. Each woman commands space like a soloist, with genuine parity. Never mind the Elysian Fields of the dead: this pattern has often seemed like an image of American democracy (which may have seemed Elysian to Balanchine after his experience in Russia and Europe between1918 and 1933).

And we have a third source for that rehearsal. Ruthanna Boris - one of those seventeen young women, who stayed in Balanchine’s orbit for many years, dancing the foremost roles in Serenade for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1944, and choreographing for New York City Ballet in 1951 – wrote an undated memoir in which she recalled that Balanchine - announcing that “we will make some steps!” - then spoke to the seventeen young women about his life in Russia (“It was revolution, bullets in street”) and his move to Europe.

“Little by little his talking became more and more like a report—less conversational, more charged with feelings of anger and distress: ‘In Germany there is an awful man - terrible, awful man! He looks like me only he has mustache - he is very bad man— he has moustache – I do not have moustache – I am not bad man – I am not awful man!’… It seemed to me he was tasting his words and trying to get past them. To the best of my memory no one knew what he was talking about. We were adolescent and young ballet dancers, mostly American, mostly aware of the dance world, unaware of governmental affairs in the world beyond it….”<15>

Look again at that opening tableau: Balanchine choreographed here as if he too had the alchemist’s stone, transmogrifying the Nazi salute in space until it became a quasi-religious vow.

The ritual that follows is similarly an exercise in metamorphosis, every staccato pause on the way taking the dancers further away from politics and danger toward a great openness to experience. In 1927, Paul Valéry had written, in The Soul and the Dance, that dance was “the pure act of metamorphosis”; and no ballet by Balanchine better illustrates the idea than Serenade. The opening upper-body ritual has no logic in terms of moment-by-moment meaning, but it shows us change in action (and then leads to ballet’s logic of turning out the limbs and torso from the body’s center). Balanchine was a practicing Christian; I like to think the start of Serenade comes close to Paul’s famous words in the first letter to the Corinthians:

“Behold, I shew you a mystery. We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed. In a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trump: for the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed. For this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality, then shall be brought to pass the saying that is written, Death is swallowed up in victory.”<17>

Balanchine has started his ballet with what could easily be an ending. But this dance prolegomenon abounds in thematic material. Even after hundreds of viewings, we keep noticing how myriad details of what follows – the bringing of a wrist towards the forehead, the sideways pointing of foot and leg, the arching back of the neck – were all introduced here, in the beginning, as a prophesy of what was yet to come.

IV.

He took pride in relating how he incorporated rehearsal accidents into this ballet. One day, a girl fell over; he put that into the ballet. Another day, another girl arrived late; he put that in, too. The incidents began to look like a story. Balanchine never worked quite that way again. What was it about Serenade that made him so receptive to chance moments of non-dance? Perhaps he could do so because he could see how those two girls were images of Eurydice. He adjusted the “girl who falls” so that she spins on the spot as if losing control before collapsing to the floor, like Eurydice at the moment of death; and in early performances (particularly in a film of a Ballet Russe performance in 1940) he then presented her supine body as if it was a corpse in its coffin. Likewise the latecomer may simply be Eurydice taking her place among the heavenly dance choir in Elysium. Who can tell now whether these Orphic fancies are truly what Balanchine had in mind?

Certainly Balanchine had hidden imagery that he seldom disclosed. His protégé John Clifford was surprised when Balanchine, during a fierce argument about the fit of movement to music, said that his choreography of the second movement in Symphony in C, the high-classical pure-dance that he created in 1947 to Bizet’s score of that name, was “the dance of the moon… The grands jetés where she gets carried back and forth at one point are supposed to be the moon crossing the sky.”<17> This was not an image that Balanchine had ever given his dancers; but many readers of I Remember Balanchine<18>, which contains the interview in which Clifford recounts this anecdote, have dutifully written of the moon crossing in the sky in that sequence. (I still don’t see a moon in those lifts, though I love watching both the moon and Symphony in C.) In 1979, Balanchine coached the dancer Jean-Pierre Frohlich in the first pas de trois of Agon, his masterpiece of 1957. Performed in black and white leotards, tights, and T-shirts to a commissioned Stravinsky score, this work has often seemed a peak of pure-dance radical invention, infusing classicism with a new high-density and “plotless” modernity that moved dance far away from drama and androle-playing. Yet Frohlich has recalled that Balanchine explained his role <illustration 15> as “the court jester”<19>. For me, this made immediate sense: it did not change my understanding of the work as a whole, but it helped me to define one aspect of its character.

It matters to notice just how Balanchine tells his stories. The interesting thing about the young woman who falls to the floor in Serenade is not the way she falls but the entrance of the corps. Fifteen young women march in on point in five different rows, like radii towards her focal point. Yet they do not rush to console or to help her. In one of the strangest images in all dance theater, they coalesce around her in the shape of a Greek theater, whereupon they simply do staccato arm exercises. Has one dancer fallen? Then the dance will continue with the corps.

We can also interpret them as another facet of the Elysian sorority around Eurydice. Such a view, however, does not quite explain their formality and their impersonal behavior. Serenade may contain fragments of myths, but it is about a larger process than any myth: the constant subordination of the dancer to the dance. So what happens next? The fallen woman, the dead Eurydice, promptly picks herself up and dances the most difficult jumps in the ballet so far. She explodes in the air only to pounce precisely back down onto the music’s beat.

As for the episode with the latecomer, what’s dazzling is that her colleagues have all just resumed the ballet’s opening tableau. Sixteen of them stand again just as they did in the beginning, yet they look quite different now: their statuesque immobility is in total contrast to the quietly informal way she, the missing seventeenth, traces her way through their ranks. (“Drama is contrast”: Merce Cunningham.<20>) Just as she takes her place to join them in the ballet’s opening ritual, Balanchine hurls two other masterstrokes. The other sixteen dancers softly turn into profile, beginning slowly to depart, as if leaving her to her destiny. And a man enters, walking toward her with the same inevitability with which they are walking away. Again, Balanchine is the master of geometry: the man’s path is a straight diagonal, the corps’ path is a straight horizontal, but both his advent and their exit are focused on her, this innocent latecomer who sees none of them. You don’t need to imagine Orpheus coming to rescue Eurydice from the realm of the dead; bu you can’t miss how mysteriously fateful this strange scene is. Balanchine fits it perfectly to the final bars of the Sonatina, so that we reach the music’s end in complete suspense.

Another of the strangest features of Serenade is that it abounds in echoes. The “mother” at the end of the Elegy enters from the same corner and along the same diagonal as another woman did in the Sonatina. Five women in the Sonatina dance in a chain that prepares us for five different women who form a chain at the start of the Russian Theme. The man who enters along the long diagonal at the end of the Sonatina prepares us for the other man who enters at the start of the Elegy (Orpheus I and II). The woman who falls in the Sonatina is echoed by one (added in 1940) who tumbles far more spectacularly at the end of the Russian Theme. The mysterious kingdom of Serenade is a land of second chances.

And so too, for Balanchine, was America. A serious case of tuberculosis in 1932-1933 had rendered him unable to work for a year. Lincoln Kirstein, after inviting him to America in 1933, kept hearing from Balanchine’s ballet friends that he had a poor life expectancy. Balanchine, left with only one functioning lung, later told a friend, “You know, I am really dead man.” But he lived in his new-found-land for almost fifty years, prodigiously prolific until a few months before his death.

V.

Balanchine liked to envisage himself meeting his composers in the next life. When he died, I wrote an elegiac essay in which I gleefully imagined the scene with all of them waiting by the elevator door to greet him as he arrived and gushing appreciatively about the fabulous things that he had made from their scores. <21> Yet prolonged acquaintance with his ballets now makes me imagine a different scenario. Gluck: “Okay, that’s a beautiful pas de deux he made to the Blessed Spirit music in my Orphée et Eurydice, but surely he could have seen that I meant it as the middle section of a da capo structure! It has to be A-B-A, but he cuts the return to A.” Tchaikovsky, who has quite a list of complaints, begins: “When I wrote my Third Symphony, I took a deliberate risk by giving it five movements. But he cut out the first movement in his Diamonds and made it just another four-movement symphony! Also I never wanted the Siloti edition of my second piano concerto – it tidies up all the irregularities in which I was changing concerto form! His Serenade I will forgive; it’s not my Serenade, but, yes, it is just as beautiful, I can see that now. But why re-order my Mozartiana? And why all that tinkering to my Nutcracker? A genius, yes, but an impossible one.” And so on.

Among all the dead composers impatiently awaiting Balanchine in paradise, I long most to overhear Stravinsky. “George and I were good friends for over forty years - and yet, the very year after my death, he makes all those ballets to my concert music as if I were writing plays about men and women! He uses my music for plots! And my blood boils about what he did to the Divertimento from Le Baiser de la fée. He cuts some of it, he interpolates another bit from elsewhere in Baiser –it’s really quitefraudulent. All right, what he created was quite beautiful –so amazingly dramatic - no way is that a divertimento!” The composer’s aggrieved ghost would be right. Balanchine’s “Baiser” Divertimento is a misnomer. It’s too profound for that name.

Stravinsky composed the complete ballet La Baiser de la fée in 1928. It is his re-telling of Hans Christian Andersen’s story The Ice Maiden as if the protagonist were Tchaikovsky, whose music is employed throughout in a modernist and neo-Romantic collage. The story chillingly illustrates Graham Greene’s point that “there is a splinter of ice in the heart of a writer.” <22> The ballet’s hero is singled out in infancy by the Fairy, who distinguishes him from other mortals by planting a kiss on his brow: a vision of the muse at her most heartless. He becomes engaged to a girl, but the Fairy, often disguised but sometimes revealing herself with terrifying clarity, keeps parting them. The ballet ends with him helplessly following the Fairy into her icy realm while his fiancée is left alone in desolation.

Balanchine first staged this complete Baiser in New York in 1937, at the Metropolitan Opera. For some fifteen years, he kept it in repertory of the successive companies to which he was attached (the American Ballet, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, New York City Ballet) until, in the early 1950s, he finally dropped it. But Stravinsky had arranged a concert suite of the ballet’s music, Divertimento from Le Baiser de la fée, in 1934, and Balanchine turned to it in 1972, as he created a flood of new ballets in celebration of Stravinsky (who had died the year before). Oddly for a Stravinsky Festival, Balanchine made major structural changes to this score. (Just to call it Suite from “Le baiser de la fée” would have been more accurate.)

In particular (as the dance scholar Stephanie Jordan first noted in 2003 <23>), he introduced, from elsewhere in the complete ballet, a dance to which he created the most poetically dramatic male solo of his career. (On YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=raQ06-0OEjQ it begins at 5.13, though this studio film scarcely suggests the impact the solo can have in the theater.) The music depicts how the Fairy’s irresistible spell begins to infect the hero. The 1972 solo, beginning with great elegance and formal charm, is an accumulating soliloquy, in which the hero’s conflicting energies and self-contradictory aspirations pour forth with uncanny seamlessness. With no histrionics, he seems both inspired and tormented, changing speed and direction in one dance paradox after another. He pivots on his own axis as if keeling over; he jumps forward while arching back; he punctuates a briskly advancing diagonal with sudden slow turns that gesture upwards and away; he softly circuits the stage with jumps that arrive in slowly searching gestures. It is a completely classical statement within a classical pas de deux, and yet it turns the drama around: it tells us that this hero is no longer the fiancé he was.

In 1974, Balanchine tinkered some more with this already remarkable non-divertimento Divertimento. He now added music from the ballet’s finale, in which Stravinsky makes a heartbreaking arrangement of Tchaikovsky’s famous song “None But the Lonely Heart.” Now, however, Balanchine omitted the Fairy that Stravinsky had signified in this music. The only two leading characters here <illustration 16> are the hero and his fiancée, who, though trying to embrace, are repeatedly interrupted by an impersonal line of women corps dancers. Yet this cruel interruption makes less impact than the way the man and the woman now part, evidently forever, as if accepting separation as destiny. They retreat <illustration 17> on separate paths that depict them both as figures of tragic isolation. Both walk with their torsos backward, unable to see where they are going. Slowly they zigzag their ways into ever greater distance from each other, without resistance. Man and woman are sundered, the ballet suggests, not by an external figure of fate but by their own internal impulses, which are just as inexorable. It’s as if, in A Doll’s House, Nora and Helmer had agreed to end their marriage without anyone slamming the door at the end. This ballet begins as a divertimento but ends as a tragic psychodrama; and the progression from plotlessness to plot, from the delight of form to the heartbreak of alienation, proceeds in unbroken sequence.

To praise Balanchine as the most musical of dancemakers is to persist in a cliché that misunderstands the full magnitude of his achievement. There are technical aspects of music – melody and harmony, in particular – of which his contemporary Frederick Ashton (1904-1988) sometimes found more in the same scores than Balanchine did. Yet this does not make Ashton, an artist dear to me, the greater artist.

It’s better to see Balanchine as an incomparable exponent of Director’s Theatre. His musicality was of a far more interventionist kind than has generally been admitted. He was not just the grateful servant of his scores; he imposed his own vision on his music, which was often an intensely dramatic vision, a vision of humans in the fullness of their relations, and where necessary he tweaked his scores to fulfill it. In the vast majority of his ballets, music and dance work in brilliant counterpoint, different voices that combine to dig deep into our imaginations and our nervous systems. Ear and eye collaborate closely and uncannily in a genre of dance theatre that, even now, takes us where we had not been before.

1, Bernard Taper, Balanchine.

2.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xd9R9S6-9E4 and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eOVhOMEijB4

3. Macaulay, The Genesis of Balanchine’s “Serenade”, 2020: www.alastairmacaulay.com. An earlier edition of this essay was published in 2015 in the American quarterly Ballet Review.

4. Balanchine calls it “Russian Theme” in his book Balanchine’s Festival of Ballet (1954), co-authored with Francis Mason.

5. See Solomon Volkov, Balanchine’s Tchaikovsky.

6.Annabelle Lyon interview, I Remember Balanchine, edited by Francis Mason.

7.Kirstein’s handwritten diaries are kept in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Quotation by permission of Kirstein’s literary executor, Nicholas Jenkins.

8.D.H.Lawrence, Selected Letters, selected by Richard Aldington, 1950, p. 18.

9.Karin von Aroldingen told this to Elizabeth Kendall, who in turn reported it to the New York Public Library symposium on Serenade, August 2015.

10.John Clifford, emails to AM, 2016, 2020.

11. Colleen Neary, email to Alastair Macaulay, 2016.

13.Kirstein, handwritten diaries, NYPL. Permission as before. When Kirstein typed up his diaries and published parts of them, he made changes; here he changes “the sun” to “sin”.

14. Balanchine in Balanchine’s Guide to the Great Ballets, 1954; and in a 1964 TV interview included in the 1983 two-part TV documentary Balanchine.

15..Ruthanna Boris, Serenade, Published in Robert Gottlieb (editor), Reading Dance, 2008.

16 Corinthians I: 51-53..

17.Clifford, I Remember Balanchine, p. 557.

18. Francis Mason (ed.), I Remember Balanchine, 1991.

19. Frohlich interview July 2019.

20.Merce Cunningham to Nancy Dalva, Mondays with Merce, 2008-2009.

21.Macaulay, “Balanchine’s World,” Ballet Review, Autumn 1983.

22. Graham Greene, A Sort of Life.

23.Stephanie Jordan, Balanchine Observed.

@Alastair Macaulay, 2022

1.Balanchine’s “Serenade”: the fourth point in the seventeen women’s opening ritual.

2.The first part (or “act”) of Balanchine’s “Liebeslieder Walzer” (1970).

3.The second part, or “act”, of Balanchine’s “Liebeslieder Walzer”.

4. The opening image of George Balanchine’s “Serenade” as caught in a 1940 film by Ann Barzel of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in Chicago (hence the blurring).

5. Tilly Losch and Lotte Lents as the two Anna’s in Balanchine’s 1933 staging of “Les sept Pêchés capitaux” (“The Seven Deadly Sins”), which was presented in London as “Anna-Anna”.

6: Adam Lüders (left) watching Balanchine rehearse his role as Robert Schumann with Karin von Arolindingen as Clara in “Robert Schumann’s ‘Davidsbündlertänze’” (1980).

7: Jacques d’Amboise and Suzanne Farrell in “Robert Schumann’s ‘Davidsbündlertänze’” (1980).

8: A screen-capture of the final scene of Balanchine’s “Robert Schumann’s ‘Davidsbündlertänze’”, with Karin von Aroldingen and Adam Lüders.

9: Aria I in Balanchine’s “Stravinsky Violin Concerto” (1972).

10: Aria II in Balanchine’s “Stravinsky Violin Concerto”.

11: Canova’s model for his second version of “Psyche Awakened by Cupid’s Kiss”, Metropolitan Museum, New York.

12: The “Dark Angel” promenaded in arabesque but her knee in the Elegy of Balanchine’s “Serenade” (1934). María Calegari in arabesque, supported by Peter Frame: New York City Ballet. The semi-recumbent heroine here is Kay Mazzo. Collection: New York Public Library.

13: Orpheus (Lew Christensen), Eurydice (Daphne Vane), and Amor (William Dollar) in Balanchine’s 1936 two-act Metropolitan Opera production of Gluck’s “Orpheus and Eurydice”. Photo: George Platt Lynes.

14: Orpheus (Nicolas Magallanes) and Eurydice (María Tallchief) in Balanchine’s 1948 Stravinsky ballet “Orpheus”.

15: Jean-Pierre Frohlich in the Sarabande solo (“the jester”) of the first pas de trois In Balanchine’s “Agon”

16: The final encounter of the lovers in Balanchine’s “Divertimento from ‘Le Baiser de la fée’”, in the scene Balanchine added in 1974. Joaquin de Luz and Megan Fairchild.

17: The final encounter and parting of the lovers in Balanchine’s “Divertimento from ‘Le Baiser de la fée’”: the scene added in 1974. Robert Fairchild with Tiler Peck.